The “Colonial Period” in Latin America refers to four centuries of history, from Columbus’ arrival on the shores of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola (now the Dominican Republic and Haiti) in 1492 to the final severance of colonial control in 1898. It encompasses the histories of hundreds of indigenous groups; the various colonizing projects of the Spanish and the Portuguese as well as the cultural, political, and economic influence of competing incursions led by the French, English, and Dutch; the active role of the Catholic Church; the impact of the Atlantic slave trade, and the forced integration of hundreds of thousands of African slaves and their descendants into distinct Latin American societies. “Colonial period” thus refers to the history of an entire hemisphere and its relationship with Europe and Africa over nearly half a millennium. Any effort to represent a complete trajectory of even one aspect of that history—such as music—would be impossible in the space available here. This chapter does thus not claim to represent a comprehensive survey of Latin American colonial music. Rather, it asks you to consider some of the extraordinary works composed and performed during this period within the context of conquest and colonization. The listening examples not only feature representative musical works, but also provoke inquiry into the colonial project itself.

What meanings did music convey for people of different groups? How was music produced and performed? What kind of cultural and political work did music do and how did it help shape what we know today as Latin America?

For indigenous peoples, European colonizers, enslaved Africans, and the diverse hybridization of communities and cultures that these groups later produced, music represented more than mere entertainment. Music could show military and political force or display economic wealth. It served as a representation of religious faith and as an important tool of conversion. Perhaps most powerfully, music—whether pre-Columbian “flower songs,” complex choral works performed in ornate cathedrals, boisterous street processions, or allegorical operas performed in colonial palaces—both reflected and influenced society. How music was performed and by whom, how it was taught, listened to, or danced to, the content of its lyrics, and even the sound of the music itself shaped the worldview of both the colonizer and the colonized.

Following a brief historical overview of colonial history and a discussion of music at the time of conquest, selected colonial musical practices are discussed through a number of thematic lenses. They include Education, Space and Place, Religion and Ritual, Material Culture, Entertainment, and Cosmopolitanism. A summary of these themes appears below.

Education: The Catholic Church initially embraced certain elements of indigenous culture as a means of evangelizing locals and the development of a colonial music pedagogy with the ultimate aim of religious conversion and the stable and unified growth of the Church in the New World. In the process, Indigenous and Afro-Latin concerns and aesthetics also entered into dialogue with European musical expressions of religion. The power of music education as a colonizing force extended beyond the initial conquest. As the Spanish extended their empire in the eighteenth century in both North America and South America, the missionary presence expanded in both regions, as did the music’s use as a tool of conversion and acculturation.

Space and Place: Where was music performed, and what significance did those spaces hold culturally and politically? Key to this discussion will be the role of the cathedral as the de facto center of the colonial soundscape, as well as how processions and outdoor celebrations strengthened colonial authority.

Religion and Ritual: Highly organized ritual, in which music figured prominently, was a central part of many of the indigenous societies encountered by European colonizers, as it was to the Europeans themselves. The chapter pays particular attention the primary ritual of the Roman Catholic Church, the Mass, and its relationship to indigenous ritual practices.

Material Culture: This chapter draws your attention to the material aspects of music making, such as the availability and manufacture of instruments and the influence of indigenous and African instruments on colonial-era music. The practical realities of evangelization and the sometimes-competing directives of Church officials in Rome influenced the types of instruments used in religious practice.

Entertainment: Secular music for entertainment played an important part of colonial life. Theater music, dance music, and popular songs entertained at the same time that they helped negotiate new Latin American identities. Improvised and orally transmitted, secular music written evidence survives of it than for religious music. Yet the secular songs and dances of the colonial era set the stage for many of the prominent genres discussed in later chapters in this book.

Cosmopolitanism: Latin American musical culture did not develop in isolation, nor did it merely borrow from sources elsewhere. Rather, it developed in dialogue with Europe and, by the end of the colonial period, the United States as well. The latest musical trends from France and Italy, as well as Spanish and Portuguese styles, sounded in Latin American cathedrals, theaters, and ballrooms, and new Latin American rhythms as well as novel variations on European forms crossed back over the Atlantic. The Atlantic slave trade continued until the 1860’s (albeit illegally), and along with human cargo it brought continuous infusions of African cultures, languages, and musical traditions, elements of which found their way into local musics. Several genres that became popular on both sides of the Atlantic, such as the zarabanda (sarabande), contradanza (contradance) and habanera, had their origins in colonial Latin America’s unique cosmopolitanism.

Columbus’ inadvertent landing in the Caribbean in 1492 soon led to a burst of exploration from Spain and its neighboring competitor, Portugal. Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella asked Pope Alexander IV for official ownership of the territories (still believed to be part of Asia) in exchange for undertaking the task of Christianizing local inhabitants. The resulting Papal bull granted Spain title to the “Western parts of the Ocean Sea, toward the Indies,” and a later version clarified and expanded Spanish dominion to include all the lands west of a north-south demarcation line one hundred leagues west of Cape Verde and the Azores. The Portuguese, feeling that this limited their possibilities for expansion, threatened war, and the two kingdoms eventually signed, in 1494, the Treaty of Tordesillas, which created a new line of demarcation some 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands. Spain would control all lands to the west of this line, and Portugal those to the east, allowing the Portuguese to claim Brazil following their discovery of the territory in 1500.

The desire for precious metals and other resources and the enslavement of native populations to extract those resources compromised the Spanish crown’s commitment to evangelization, as the project of true conversion (rather than just mere baptism) conflicted with the demands of wealth generation. Harsh labor conditions and abuse combined with unfamiliar European diseases had a disastrous effect on native populations. Estimates of the island’s population at the time of Columbus’ arrival range from several hundred thousand to over one million. By 1518 the population had already been decimated to about 30,000. The Spanish soon began to look elsewhere for labor and natural resources, conquering Puerto Rico in 1508 and Cuba in 1511. The native populations suffered tremendous losses there as well, and in neighboring islands. The Spanish responded by importing increasing numbers of African slaves and they also began to investigate the Latin American mainland.

Africans arrived in the New World almost as soon as Europeans did. Free black sailors accompanied the earliest expeditions in 1492. Not all arrived in the Americas of their free will, however. The Portuguese capture of the strategically-located North African city of Ceuta in 1415 led to increasing Portuguese exploration of and trade with the West African coastline. While initial trading between the Portuguese and West African groups focused on the acquisition of African goods (including gold, iron, copper, textiles, and salt), by the 1480s it became more common for European goods to be traded for slaves. In the final decades of the fifteenth century, Portuguese traders bought and exported over two thousand slaves annually. Over the next century, the slave trade grew and continued to do so for more than three hundred years, eclipsing all other relations and trade between Europe and Africa. From 1513 until the 1860s, Africans forcibly brought to the Americas maintained, to varying degrees, elements of their religions, languages, and cultures—and their musics.

The conquest of the mainland began with Hernán Cortés’ overthrow of the Mexica (Aztec) empire from 1519-1521. [Note: Most historians prefer to use the term “Mexica,” rather than the popularly-used term “Aztec,” to describe the collection of Nahuatl-speaking peoples who formed the Mesoamerican empire in place at the time of Cortés’ arrival. Some writers use “Mexica” to refer to the empire itself and “Nahua” to refer to the people of this linguistic group and their cultural practices. In this text, I will be using “Mexica” broadly, to cover both meanings.] Spurred by discoveries of gold and other precious commodities, Spanish control over the continent quickly spread. In 1526 Francisco Pizarro made first contact with the Inca; six years later he overthrew and executed the Inca leader Atahualpa and seized control of Cuzco. With Latin America’s two great urban empires thus defeated, an age of European colonization began in earnest.

Colonialism in Latin America developed differently from the English colonies, which were governed by a remote authority. Initially, Spain divided its Latin American holdings in two primary administrative divisions: the Viceroyalty of New Spain, which included what is now Mexico, Central America, and much of the southern United States, as well as the Philippines and the Caribbean; and the Viceroyalty of Peru, which included the entire western third of South America. In 1717, the Spanish split up this large territory and created a new jurisdiction, The Viceroyalty of New Granada, corresponding to present-day Panama, Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela, and parts of Brazil and Peru, as well as Trinidad and Tobago. Finally, Spain established the Viceroyalty of Río de la Plata, containing present-day Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay and Uruguay in 1776 (see Fig.2.1). A local viceroy, who functioned as a surrogate for the Spanish crown in his jurisdiction, governed each of these jurisdictions.

Unlike the Spanish, the Portuguese initially approached their new territory as amaterial resource but not as a colony for settlement. The crown leased out rights to a number of companies who extracted the rich, red-grained Brazilian wood known as dyewood (the favored wood for making violins and other musical instruments), parrots and other exotic animals, and captured some indigenous slaves. Spain for the most part accepted the juridical basis for Portugal’s claim on Brazil, arguing only about boundaries, but other emerging colonial powers did not recognize the validity of the original Papal bull. Eventually the Portuguese king, João III determined that the only way to stake a lasting claim on the new territory was to settle it. The first four hundred settlers arrived on the mainland in 1530, and Brazil was a remotely-governed colony until 1763, when it gained the status of a viceroyalty. Brazil’s status changed again from 1808 to 1821 when the Portuguese royal family moved the seat of the throne there to escape Napoleon’s advancing troops.

The Roman Catholic Church permeated colonial life. In the Spanish colonies, Church officials’ loyalties extended to both Rome and the Spanish Crown. In 1508, just before the Conquest of the mainland began in earnest, a Papal bull established the patronato system which gave the Crown authority to control the clergy in its American territories. While the Pope continued to be the spiritual leader of the Church, the Spanish king and his representatives coordinated religious activities. The religious orders administered educational and charitable institutions such as schools, hospitals, and orphanages. Lay (non-clergy) brotherhoods, or confraternities, known as cofradías in Spanish and irmandades in Portuguese, helped to organize local religious festivals, funerals, and other special occasions and, arranged for music to accompany services. All of these institutions became important sites for music making.

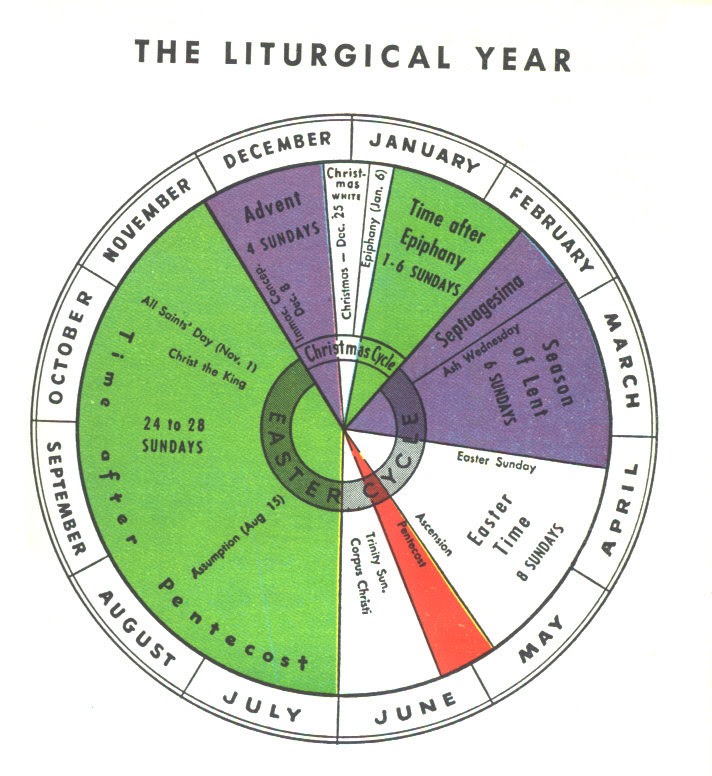

The Church calendar, with its periods of penance (Lent), celebration (Easter, Christmas), reflection (Advent), and individual feast days, mapped itself onto daily life throughout Latin America, merging local traditions with European practices (Fig. 2.2). South America’s location in the southern hemisphere meant that the seasons for religious holidays there are reversed from the way they are experienced in the northern hemisphere (i.e. Christmas takes place during the hottest summer months, Easter in the Fall, etc.), which helped to foster new traditions. Feast days such as the celebration of Corpus Christi, discussed later in this chapter, became sites for the negotiation of local identities and religious beliefs, as the descendants of Europeans, Africans, and indigenous groups created new forms of religious expression, often expressed in musical terms. Such feast days have continued to shape religious and musical culture throughout Latin America into the present, as can be seen in subsequent chapters.

In their new territories, the Spanish (and later the Portuguese) pursued a development model that replicated renaissance ideals for both urban planning and civic government. Just as European cities asserted their identities through musical displays in architecturally impressive cathedrals and palaces, the two new viceregal capitals, Mexico City and Lima, as well as other prominent cities, such as Puebla, Oaxaca, Cuzco, Sucre, and Bogotá, proclaimed their status not only through elaborate new architecture, public works projects, and the transformation of pre-existing indigenous monuments, but through the musical use of civic spaces. Elaborate multi-voiced, or polyphonic, compositions resounded from cathedrals and churches, and musicians sang and played the latest compositional styles from Europe. By the eighteenth century, Latin American cities hosted performances of new Latin American operas and other repertoire. Such music powerfully asserted identity, not merely Spanish, Portuguese, or Catholic, but increasingly local.

Many historians prefer the term “viceregal period” to “colonial period” when discussing these centuries of European control, as it emphasizes the considerable autonomy that the viceroyalties enjoyed from Spain. However, the degree of autonomy varied greatly by region. Cuba and Puerto Rico, for instance, experienced much stronger direct economic, military, and cultural ties with Madrid than they ever did with Mexico City, owing in large part to Cuba’s strategic military location and Havana’s important role in maritime trade. In rural and remote regions such as the Southern Cone, the administrative and cultural imperatives of missionary groups often had a greater impact than overarching viceregal experience. In order to broadly address all of these cases, I will be using the term “colonial period” throughout this chapter. In addition, the slightly more political term “colonial” calls our attention to the power relationships that fundamentally shaped new musical cultures.

In the 1490s, the indigenous population of the Caribbean and mainland Latin America is estimated to have numbered between thirty-five and fifty-five million people. This population varied widely, comprising over 350 major tribal groups and more than 160 distinct languages. European explorers encountered—and developed strategies to conquer—three different types of indigenous societies: 1) nomadic groups who relied on hunting, and gathering for subsistence; 2) small, sedentary groups who relied on agriculture; and 3) densely populated and urbanized societies with highly stratified religious and governmental hierarchies and well as organized militaries and advanced architectural and scientific expertise. Groups such as the Inca, Maya, and Mexica correspond to the latter category. While they represented only a fraction of the overall indigenous population, we know considerably more about their musical activities than we do of other groups, as Europeans documented contact with them. Of course, the European invaders or missionaries who wrote about indigenous culture viewed it through the bias of their own preconceptions, leaving us with many questions. Surviving instruments and iconic data provide another source to help reconstruct elements of pre- Conquest music cultures. This section primarily examines Mexica music-making using available sources while recognizing that the urban musics of Mesoamerica represented but one music culture flourishing in Latin America at the time of the conquest.

Music constituted an important part of social, civic, and religious life in the Americas long before the arrival of Europeans. In Mexica society, musicians enjoyed high social status. They trained in special schools, known as cuicacalli, dedicated to the performing arts. As in modern Western conservatories, expert faculty taught specific instruments and, while students received general training in all aspects of the performing arts, advanced students would specialize in a chosen instrument. Musicians accompanied the most sacred rituals, performed for dances, celebrated births and mourned deaths, and accompanied soldiers into battle. While we can never know how Pre-Columbian music sounded to those that created and consumed it, archeological evidence and descriptions written by early Spanish explorers stress an enormous diversity of musical expression.

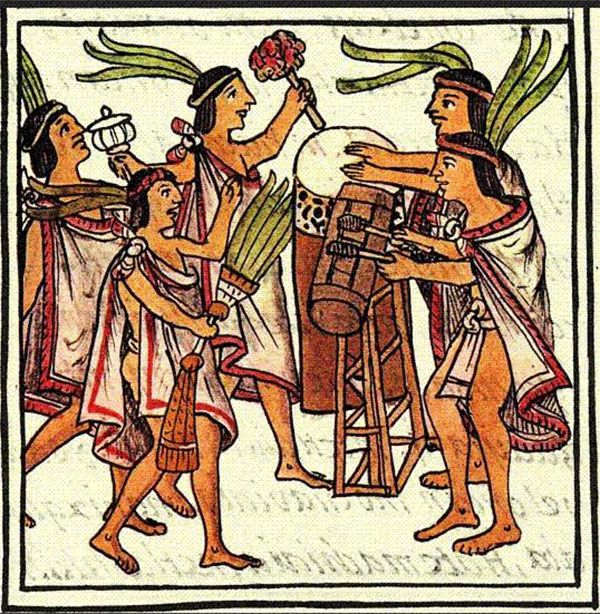

Prior to contact, indigenous groups across Latin America made vocal music and played a wide variety of percussion instruments and aerophones. In Mesoamerica, for example, the Mexica used two types of ritual drums, a split log drum called teponaztli and the single-headed huehuetl. An idiophone, the teponaztli’s sound was produced by rubber–tipped

mallets that drew two pitches from the tongues of wood created by the H-shaped slit carved into the drum (Fig. 2.3). From extant copies of the instrument it seems that the most common tuning for the teponaztli was a fourth or a fifth apart. The huehuetl (Fig.2.4) was a membranophone; a jaguar skin stretched across the top of the upright cylinder could be tightened and tuned so that the player, striking the membrane with his bare hands, could produce two tones a fifth apart. Pictoral evidence as well as sixteenth-century written accounts confirm that the two instruments were commonly played together. Spanish explorers described the drums’ dramatic power, and this may help explain Spanish soldiers’ slaughter of Mexica drummers in the massacre at Tenochtitlan in 1520 (See Box). Yet while Spanish explorers wrote about the threatening din such

drums produced, and their use in both battle and in human sacrifice, their descriptions of the music itself are vague. Therefore neither the actual rhythms produced nor the meanings such rhythms generated can be known to us today. Furthermore, it is likely that what the Spanish identified as individual pieces or songs were actually part of much longer and complex compositions and music dramas that may have lasted hours or even days. The Cantares Mexicanos, a sixteenth-century compilation of ninety-one xochitl/cuicatl, or “flower songs,” provides a tantalizing glimpse into the Mexica’s spiritual worldview and their adaptation to Christianity. One of the most striking elements of the Cantares is that it is the only sixteenth-century source that provides extensive notation for drumming, a syllabic notation, or solfege, that appears to refer to both pitch and rhythm. Using four syllables—ti, to, qui (pronounced “ki”), and co—the

manuscript notates patterns at the beginnings or sectional divides of individual texts. Thus the syllables are grouped into patterns such as “tocotico tocoti” or “toco tico tocoto, tiqui tiqui tiquiti.” Some scholars have suggested that such notation uses vowels to refer to pitch, with “i” being the higher pitch and “o” the lower, while consonants and their use in combination could refer to rhythmic pattern. Such readings are largely conjecture, but many scholars of pre-conquest music have tried their hand at interpreting this notation and providing contemporary listeners with an idea of what the drums may have sounded like

Sixteenth-century explorers extensively described the use of aerophones, both in Mesoamerica and the Andean region. Archeologists have documented a variety of flutes in Mesoamerica, and surviving aerophones from the Andean region are especially diverse, including conch-shell qqepa trumpets, antara panpipes, and the end-blown kena and pingullo flutes. Many of these instruments are still used today (see Chapter 8). As with the Mexica, Incan music accompanied all aspects of social, religious, military, and civic life.

In conquering the territories of the New World and its inhabitants, Spanish colonizers utilized strategies that had already served them effectively in the expulsion of the Moors from the Iberian peninsula and the conversion of those that remained. They seized and destroyed sites with significant religious and political significance and often repurposed them, rebuilding Christian churches and civic buildings in the same location. The Spanish viewed the saving of indigenous souls as justifying their control of the region, and music became a key part of this campaign.

In his earliest explorations, Hernán Cortés traveled with both clergy and musicians, and he would direct them to sing Mass in every new town and settlement that they entered. The urban civilizations of Mesoamerica and the Andes placed a high value on ritual spectacle, a trait that they shared with the European invaders. The instrumental and vocal music-making that characterized the Roman Catholic Mass thus shared a powerful ritual aesthetic. Cortés’ savvy awareness of the importance of musical ritual may have helped him conquer the Mexica; he even interrupted his early negotiations with Moctezuma to construct an altar and have a priest sing the Mass. Cortés’ prioritization of music may have gone too far, however, when he insisted on bringing a contingent of musicians along with him on a failed expedition to control territory to the South. The under-supplied group ran out of food and resorted to eating their horses and then to eating each other!

As increasing numbers of missionaries arrived in the new territories, they established music instruction along with basic religious instruction. Indigenous converts, or neophytes, invariably learned singing, solfege, and instrumental music. An important figure in this process was a Franciscan friar named Pedro de Gante who worked in New Spain from 1523-1572. Fluent in Nahuatl (the main language of the Mexica), Gante came to understand the important role that singing and dancing played in indigenous belief systems, and he indulged local preferences for elaborate rituals while overlaying them with Christian theology. “Upon [. . . ] realizing that all their songs were composed to honor their gods,” he wrote, “I composed a very elaborate one myself.” Gante adapted many aspects of indigenous culture in his campaign to convert and educate natives, staging ornate ritual processions in which the locals danced in costumes painted with Christian symbols or depicting religious figures. He focused much of his educational efforts on children, who often proved more receptive than adults. Gante set up schools in which he translated biblical themes into Nahuatl and set them to familiar liturgical melodies, known as plainchant (often referred to as “Gregorian chant”). In these early years of the conquest, the Vatican directly supported missionaries’ appropriation and adaptation of local cultures—and even local religious expression—as long as it did not directly conflict with Christianity.

The teachings of Gante and other like-minded missionaries had an enormous impact. Many local inhabitants rapidly converted and learned European music. Wind instruments (such as shawms, sackbuts, and flutes) held a particular attraction, perhaps because they most readily corresponded to indigenous preferences for bright-sounding aerophones. Neophytes quickly mastered the skills necessary to play these instruments and to sing European polyphony. In a relatively short time, even the smallest towns had their own church musicians. By 1576, only 57 years after the conquest began, an estimated 1,000 church choirs existed in New Spain, and elaborate music programs had been established in major urban centers. As early as 1530, the neophyte choir in the Mexico City cathedral impressed visitors so much that it earned the reputation of rivaling the chapel choir of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Most cathedrals preferred to employ organists and chapelmasters from Europe, yet there simply were not enough of these musicians to fill the necessary posts, and many cathedrals hired indigenous singers and instrumentalists. Later on, mestizo musicians as well as musicians of African descent joined their ranks.

As mentioned, priests occasionally employed indigenous languages, rather than Latin, in their religious compositions. While many of these sound purely European in everything but language, scholars believe that some composers used actual indigenous melodies as the basis of European-style works, particularly in areas with heavily indigenous populations, such as the Peruvian city of Cusco. The anonymous Quechua hymn, “Hanacpachap cussicuinin,” (The Bliss of Heaven) exemplifies this trend. (Listening Example 2.1) Published in 1631 as part of a manual for priests, it served as a processional entrance hymn, or introit, to honor the Virgin Mary, and it is the first published polyphonic work in the New World. The original manuscript is set for four voices and contains twenty verses, each containing five eight-syllable lines followed by a four-syllable phrase. In the original manuscript, this last four-syllable phrase is printed in italics and often forms a poetic link to the text of the next verse. The poetry itself contains metaphoric imagery that refers to both Christian and indigenous belief systems. Verse two, for example, refers to the Virgin Mary as the bearer of the Christ Child, using common Christian metaphors of the lily, the “white shoot,” and the long wait of Advent.

Uyahirhai muchascaita

Diospa rampan Diospamaman

Yurac tocto hamancaiman

Yupascalla, collpascaita

Huahuaiquiman suyuscaita

Ricuchillai

Hear my prayer,

Litter of God, Mother of God,

White shoot of the lily,

Worshipped, my barren state,

Show me your son,

Whom I await.

The thirteenth verse, however, speaks of the life-giving sustenance in local terms—the corn harvest and palm fruit—and it specifically refers to images with powerful ritual significance to the Inca. These include the color red, reserved for royalty, and references to the paving stones of the temple (rather than the Church).

Ñucñu ruruc chunta allqui

Runacnap munai callcha

Pucai pucai çumacpallcha

Sutarpu tutuchec callqui

Titu huache ñauillaiqui

Quespit huampu

Sweet fruit of the chonta palm,

Fine corn harvest of the people,

Fair gentian flower crimson red,

Paving stones for the temple,

Sustenance from the gaze of your eyes

Translucent wave

The four-voice setting is homophonic, meaning that all of the voices move together; they pronounce the syllables simultaneously, much as in the four-part setting of a church hymn today. The meter is slow and regular, appropriate for processional music; you can imagine a procession slowly winding its way through the streets and into a church as each of the twenty verses are sung to the same music.

The music itself is quite straightforward. The first two lines of text are set in a melodic arc, with the first line ascending and the second gently descending. While the verses consist of five eight-syllable lines, followed by the four-syllable ending phrase, the musical phrases divide into two halves, with each half being made up of 3 + 3 + 4 bars. Just as the final four-syllable phrase of text acts as a linkage to the poetry of the following verse, the internal four-bar phrase connects with the musical material of the second half by setting up a light syncopation that is heard again in phrases four and five. The final four-bar phrase, which coincides with the final four-syllable verse line, stands out for its slower, declamatory setting. In the following listening example , the entire verse is played through once on instruments. A choir then sings the first verse (of twenty) of the hymn.

Instruments, especially wind instruments, were widely used in Catholic religious music in Europe and in the colonies. Musicians played the louder wind instruments, such as the shawm and trumpet, for outdoor religious processions and celebrations, but they also played them in indoor celebrations of the Mass alongside bowed strings, harps, flutes, and even drums. The vibrant and occasionally boisterous use of instruments eventually attracted the attention of Vatican officials. The Council of Trent, a conference of Church authorities that met in the Alpine city of Trent (now in Italy) from 1545-1563 to outline the Church’s response to both the Protestant Reformation and to perceived abuses and extravagances within the Church itself, had a direct impact on colonial music-making. The Council issued directives curtailing polyphonic practices and instrumental performance that detracted from the solemnity of Mass. They banned instruments considered loud or shrill (shawms, trumpets, sackbuts) from liturgical use, and instruments associated with popular music such as flutes and viols. In their place, the Council advocated that organs be used to accompany liturgy. The Council’s instrumental ban, and particularly its singling out of “shrill” wind instruments, prohibited precisely the type of musical expression in which indigenous musicians were most visible (and audible). It signaled a radical shift in the approach towards colonization, rejecting the syncretic, “anything goes” approach to indigenous culture that characterized early evangelism. This hard-line attitude culminated in 1577 when the Spanish Crown forbade further inquiry into native history and religion and banned the publishing and distribution of materials by Catholic friars that contained such information.

The Church’s initiatives met with spotty success; instrumental music continued to be an important part of colonial religious activity. Efforts to introduce the organ, however, proved hugely successful. By the end of the sixteenth century, large churches and cathedrals had two, or even three of the instruments as well as a smaller, portable one used for outdoor processions. The demand for organs, and the expense of importing them, gave rise to local manufacturers, who produced them in both New Spain and Peru. Many independent organ makers were indigenous artisans who had been taught instrument-making skills by missionaries, especially the Jesuits, who arrived in Latin America in the mid sixteenth century. Over the next two centuries, until their expulsion in 1767, Jesuit missions spread across the less populated regions of the continent, including what is now Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Uruguay, and Paraguay

The Mass is the central religious ritual of the Catholic Church. It consists of prayers and readings organized around a ritual reenactment of the Last Supper, known as the celebration of the Eucharist. The texts spoken or sung during the Mass are of two types: those present in every Mass and those that change according to the occasion. Some prayers, such as the Kyrie (Lord have mercy), Gloria (Glory to God in the highest), Credo (the Creed), Sanctus (Holy, holy, holy), and the Agnus Dei (Lamb of God) are present in every celebration; that is, they are performed daily. These five unchanging texts are part of what is known as the Ordinary of the Mass. Other texts intended to draw attention to specific days in the Church calendar, such as Christmas, Easter, or Pentecost, feast days for particular saints, or the visit of a dignitary. Such days required appropriate texts and music to underscore their importance. These more “custom” texts formed what is known as the Proper of the Mass and include the Introit (Entrance hymn), Gradual, Alleluia, the Offertory, and Communion.

Most frequently, the Mass was sung in plainchant. Monophonic and metrically free, plainchant conformed well to the conditions of the New World. It could be performed by the priest alone or with a choir, if one was available. In Europe during the Middle Ages, plainchant had been categorized according to the scale utilized for each melody, known as mode, and chant melodies utilized pre-existing melodic figures and formulas in a process known as centonization. Such processes made learning and retaining chant melodies easier, aiding the Roman Catholic Church in unifying religious practices across Europe. They proved similarly useful in the New World colonies. Once trained choirs had been established, they could move beyond plainchant to sing polyphonic compositions, allowing Latin American cathedrals to resound with the same sophistication as their European contemporaries.

In the first century after the conquest, choirs typically performed polyphonic Masses a cappella, without instrumental accompaniment. If instruments did play along, they merely doubled or reinforced the vocal line. In the seventeenth century, composers often juxtaposed and intermingled works for two separate choirs in what is known as polychoral style. Occasionally instruments such as organ, harp, or bassoon accompanied these polychoral works.

A key composer of the polychoral style was Juan Gutiérrez de Padilla (1590-1664). Born in Málaga, Spain, Gutiérrez de Padilla emigrated to New Spain in 1622, where he served in the Puebla cathedral (Fig. 2.7) as assistant to chapelmaster and composer Gaspar Fernandes and took over the position following Fernandes’ death in 1629 Gutiérrez de Padilla composed in all of the important sacred genres of the day as 1629.

well as writing vernacular villancicos (see below). Some of his liturgical works are polychoral and he creates a great variety of sound by juxtaposing one group of singers and instruments against another. This type of writing is shown to dramatic effect in one of his Masses, the Missa Ego flos campi.

The title of Gutiérrez de Padilla’s Missa Ego flos campi is based on a preexisting polyphonic work, a setting of the Christmas song, “Ego flos campi” (I am the flower of the field), now lost. The Mass is impressively beautiful and surprising, as the two choirs sometimes sing back and forth to one another in what’s known as antiphonal style. At other moments, the four voices of each choir (eight lines in all) weave in and out in overlapping patterns, creating a tapestry of sound that recalls the multicolored play of light coming through a stained glass window. Still at other times, particularly at important moments in the text, Gutiérrez de Padilla marshals both choirs and has them deliver the text together, in the same rhythm. This change in delivery, and the sheer, sonic power behind it, can be truly dazzling.

The Missa Ego flos campi’s text settings are unusual for the Mass Ordinary. Remember that texts from the Ordinary are unchanging. In the Middle Ages, composers could make a setting of the Ordinary “Proper” by adding text specific to a particular occasion. By the second half of the sixteenth century, however, such practices fell into disuse, having been largely banned by the Council of Trent. Here, however, Gutiérrez de Padilla doesn’t tailor the Mass for a special occasion; rather, he creates refrains out of parts of the original text that stress the celebratory and evangelical aspect of Catholic theology. In the Credo, for instance, he creates a refrain with the word, “credo” (I believe). Normally, this word is not sung by the choir, but is instead intoned by the priest. Here, however, the word serves as a repeated profession of faith, providing a sense of evangelical zeal. At the end of the composition, Gutiérrez de Padilla creates a similar refrain out of “confiteor” (to acknowledge/accept), which is repeated three times.

Far from being a rote iteration of religious doctrine, the Credo is highly expressive, using particular textures or melodic or rhythmic gestures to bring out the meaning of individual words, a technique referred to as “word painting.” For instance, at the words, “et descendit de coelis” (and descended down from heaven) we hear the antiphonal choirs sing a falling motive. While this type of gesture is common in European polyphony of this period, it also resonates powerfully with the Mexica belief that both divine spirits and songs descended from the heavens. For the Mexica, the act of singing represented the physical expression of a spirit presence descending to earth through the lips of the singer. Song 70 of the Cantares Mexicanos begins, “In this place of scattering flowers I lift them up before the Ever Present, the Ever Near. Delicious are the root-songs, as I, the parrot corn-tassel bird, lift them through a conch of gold, the sky songs passing through my lips.” Padilla’s use of the descending motive represents accepted European compositional practice, a practice performed in cathedrals across New Spain. There is no evidence that he was aware of the metaphoric connections to indigenous theology. However, recognizing these resonances in the Missa Ego Flos Campi offers us an opportunity to consider how similarities in religious metaphor might have aided the syncretic appropriation of Christianity by indigenous cultures.

Note Gutiérrez de Padilla’s use of a slow homophonic declamation at critical theological points, “et incarnatus est” (and he was made flesh) and “et homo factus est” (and he was made man). The work’s presentation of the crucifixion is surprisingly lively: the dancelike rhythms of the choirs already look past the death and burial (passus et sepultus est) to the resurrection. The text, “et resurrexit…et ascendit in caelum” (he was resurrected….and he ascended into heaven), bursts out with joyous, ascending lines that seem to spiral up to the heavens.

A shift in the composition of liturgical music took place in the early eighteenth century, mirroring European trends. Composers highlighted textural contrasts, especially between solo singing and choral sections, and they divided settings of the Mass Ordinary into smaller fragments, which included elaborate and virtuosic arias, much in the style of Italian opera. The instruments in the orchestra became increasingly independent. They no longer served merely to support the vocal lines, but increasingly became more active and interesting, adding new colors, movement, and texture to the music. In Mexico, much of this shift can be witnessed in the polychoral Masses of Ignacio Jerusalem (1707-1769), an Italian-born composer and violoncello virtuoso. Many consider Jerúsalem’s work to exemplify the arrival of the modern, “galant” style of composition in New Spain, characterized by contrasting segments that showcase lightly accompanied homophony, rhythmic variety, delicate, refined ornamentation, and an overall sense of simple, and often lighthearted, elegance. Jerusalem’s Masses, written for the Cathedral in Mexico City, juxtapose block chordal movement in the choir, rapid figurations in the orchestra that provide a sense of motion, and lyrical and expressive solo writing. In this sense, Jerusalem’s music closely resembles that of his Brazilian contemporary, José Joachim Emerico Lôbo de Mesquita, discussed below. Another fine example of the galant style is found in the music of Esteban Salas y Castro (1725-1803), a Havana-trained composer who became the music director of the Santiago de Cuba Cathedral in 1764 where he enjoyed a prolific career, composing over ninety liturgical works plus a large number of lighter works known as villancicos (discussed below) for the Christmas season.

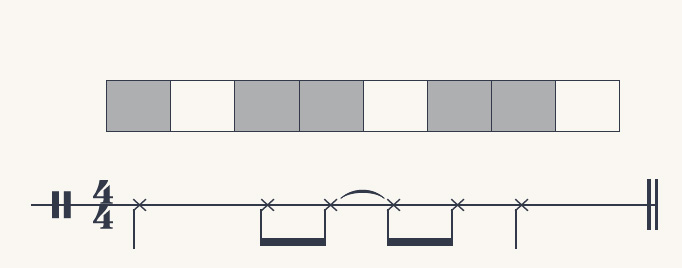

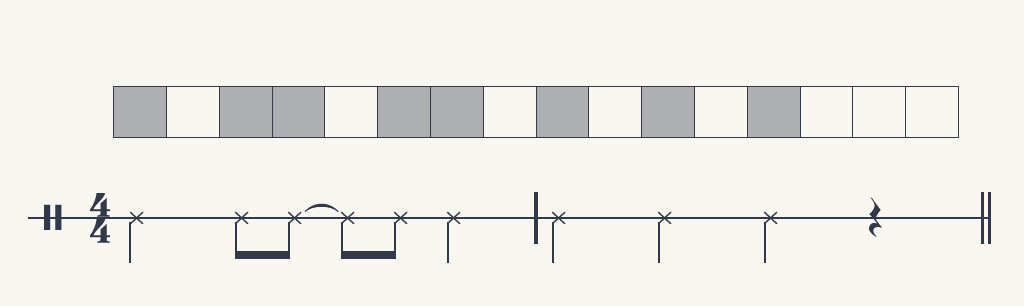

The villancico represents one of the most prominent musical genres throughout the colonial era. Most often performed by a chorus with instrumental accompaniment, villancicos are lively and often feature rhythmic groupings of two against groups of three, recalling popular dance music. Typically, they exhibit a two-part form made up of couplets (coplas) and a choral refrain (estribillo), although the genre absorbed a variety of formal deviations (see example 2.7). Latin American villancicos used religious, non-liturgical texts that often referenced elements of secular life, such as drumming or dancing, or the sounds of the street. Especially popular at Christmastime, they often accompanied processions that reenacted Mary and Joseph’s journey to Bethlehem.

By the seventeenth century, the villancico played a fundamental role in the religious life of New Spain. Performers in convents or monasteries often grouped them into suites of eight or nine pieces to be included in the celebration of the Divine Office. Villancicos could be worked into the Mass as well, and bishops often solicited the composition of new villancicos for their church services. Whereas music for the liturgy sounded awe-inspiring and removed from the realities of daily life, the villancico, and its dancelike and boisterous relative the jácara (xácara), sought to represent the popular.

Sung after the responsories and intended to enliven the service, villancicos included comic plays on words, caricatures of local racial or ethnic groups, as well as the use of dance instrumentation, hand percussion, and drums. On occasion, viols or the organ, as well as wind instruments such as recorders, shawms, cornets, crumhorns, and sackbuts accompanied them as well. The blend of secular and religious elements present in villancicos made them particularly adaptable to local tastes. In manuscripts across Latin America we find them composed in a variety of languages including Nahuatl, Quechua, Catalán, Galician, and Spanish, as well as some that use African-influenced dialects. The power of villancicos to entertain congregations alarmed Church authorities as much as it attracted them as a tool for moral instruction.

The Mexican poet, musician, intellectual, and nun Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1648/51-1695, see Box 2.2), was a prolific writer of villancico texts, and she grouped them into sequences of eight or nine to coincide with the sections of Matins. Each villancico thus honored a particular saint. From her biographers we know that she largely taught herself to compose. Evidence of her relationship with music can be found in the sizeable body of literary works that she produced during her lifetime. She used musical metaphors and musical imagery continuously in her poetry, philosophical writings, theater works, and in texts actually meant to be set to music, such as villancicos. She followed current fashion by including references to the various dialects and customs of Mexico. Because of the villancico’s connection with popular culture, Sor Juana could include controversial elements in her texts and assert her politics in a way that evaded censorship by Church officials. The text below recalls the erotic allegory of the biblical Song of Songs’ as well as the Virgin Mary. However, Sor Juana recasts these Christian themes in a local fashion, describing the Bride as a brown-skinned woman tanned by the sun. In this way she created solidarity with indigenous, black, or mestizo congregants and evoked the locally powerful image of the Virgin of Guadalupe. An excerpt from one of her villancicos appears below. In it, you can clearly see both the villancico’s formal structure as well as the author’s woman-centered theology.

Estribillo

Morenica la Esposa está

Porque el Sol en en rostro le da

Dark-skinned is the Bride

because the Sun shines in her face

Coplas

Del Sol, que siempre la baña,

está abrasada la Esposa;

y tanto está más hermosa

cuanto más de … 1 se acompaña

nunca su Pureza empaña,

porque nunca el Sol se va …

from the Sun, that always bathes her

the Wife is seared/embraced*

and thus is more beautiful

the more He accompanies her

her Purity is never tarnished

because the Sun never goes away…

Estribillo

Morenica la Esposa está

porque el Sol en en rostro le da

Dark-skinned is the Bride

because the Sun shines in her face

Coplas

Negra se confiesa; pero

dice que esa negregura

le da mayor hermosura:

pues en el Albor primero,

es de la Gracia el Lucero

el primer paso que da

She acknowledges she is black; but

says that such blackness

gives her greater beauty:

for at the first Dawn

it is from its Perfection

that the Morning Star first shines.

*the participle “abrasada” makes a phonetic pun between the two verbs “abrazar,” (to embrace) and “abrasar,” (to sear).

Portuguese-born composer Gaspar Fernandes (1565-1629) is also known as an author of villancicos. He began his professional career in the New World in 1599 as organist of the Guatemala cathedral. Seven years later he became chapelmaster of the Puebla cathedral, where he remained until his death in 1629. While in Puebla, Fernandes wrote a number of villancicos that demonstrate his stylistic diversity and his ability to work with multiple languages, including Spanish, Portuguese, Afro-Spanish dialects, and Nahuatl. Of the latter, “Tleycantino choquiliya” and “Xicochi conetzintle” exemplify the villancico’s strong association with the Christmas season.

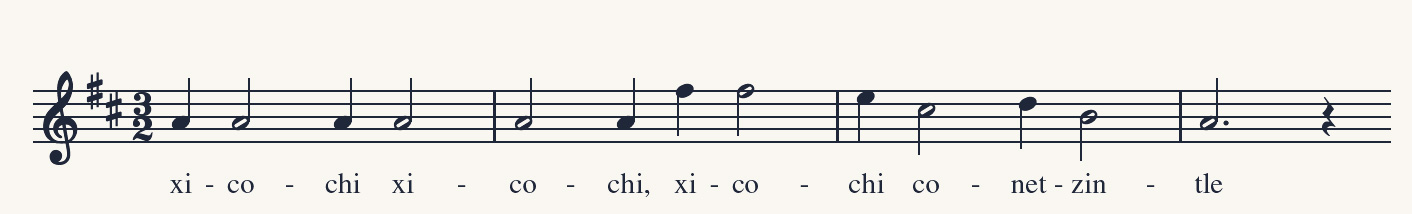

A lullaby to the Christ Child, “Xichochi conetzintle” (Listening Ex. 2.3) is a short, simple, and expressive work. Only twenty-one measures long, it deviates from standard villancico form in that it lacks an estribillo, making it technically a chanzoneta, one of the many formal structures absorbed into the villancico genre. It shares with other villancicos its syncopation, its mixing of religious themes with the local vernacular, and its sense of graceful, ebullient joy.

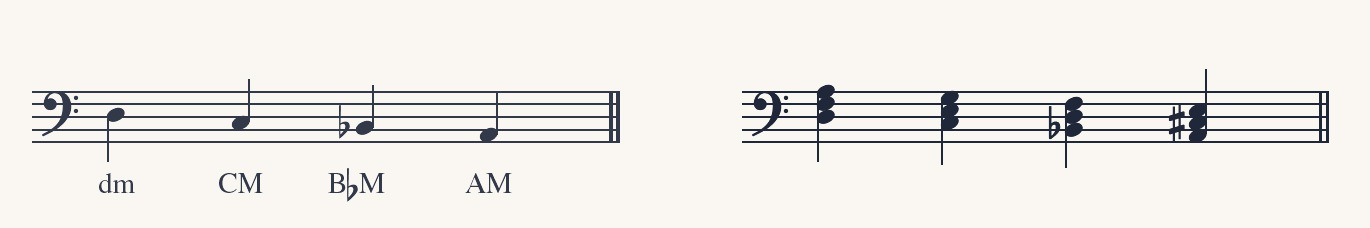

The repeated “short-long” rhythmic pattern blends the familiar rocking motion of a lullaby with the dance-inflected expectations of the genre, creating a lilting accent on beat three within the 3/2 meter, as can be seen in the alto-line excerpt below. (Ex. 2.1)

Additionally, Fernandes arranges the text so that natural stress accents (which in compound words tend to be on the antipenultimate syllable) fall on longer notes, preserving the quality of the language and working against the Spanish tendency for penultimate syllabic stress. Aligning itself with Baroque preferences for homophonic texture rather than elaborate counterpoint, the setting contrasts solos by the contralto voice with full choral responses in concertato style.

Villancicos written on texts that pretended to mimic the dialects spoken by African slaves entertained audiences throughout Latin America (and Spain as well). Known as villancicos de negros, such pieces continue to entertain audiences today, even as the highly racialized and often belittling lyrics pose a quandary for performers. An example of this genre can be found in the work Juan de Araujo (1646-1712), a La Plata-born composer who held choirmaster posts at both the cathedrals of Lima and La Plata (Sucre) after spending some years in Panama. His “Los coflades de la estleya” is a Christmas villancico, sung from the perspective of members (“coflades” or “brothers”) of the “Confraternity of the Star,” a lay-religious brotherhood similar to the Brazilian irmandades discussed earlier. The Spanish lyrics are written in a dialect that mimics the accentuation and slang of the black vernacular. The text carries a dual meaning. The characters’ proposed journey to Bethlehem implies that they might be North Africans, strengthening their allusions of kinship with the three Wise Men (who they suggest have come from Angola) and particularly to “Gasipar” (Gaspar), one of the three who was frequently represented as African in Europe at the time. At the same time, the overtly New World quality of the black Spanish dialect, along with the shifting syncopations that occur within the 6/8 meter, merge the tale of the original Christmas journey with the spectacle of local Christmas processions and festivities.

While the first two centuries of Spanish colonization saw the active conquest and suppression of one civilization and vibrant efforts to construct another in its place, Portuguese colonial endeavors in Brazil proceeded quite differently. Portugal initially concerned itself less with evangelization than Spain did, and as a result religious organization got off to a slower start in the new colony. Brazil did not create elaborate networks of cathedrals with schools to train indigenous converts in music. Additionally, the Portuguese more systematically adopted the reforms indicated by the Council of Trent than did the Spanish, and that may account for a relative lack of written music from the early colonial period. While it appears Brazilian chapelmasters did include polychoral and polyphonic works in their repertoire, they preferred simple, four-part harmonizations of Gregorian chant. Finally, Portugal fell under the influence of Hapsburg Spain from 1589 and only regained its independence in 1668, with clashes continuing until 1713. This political instability caused considerable economic weakness, which helps to account for a rather low musical output. In the eighteenth century, increasing political stability and the growth of both the economy and the population corresponded with an increase in musical activity.

Colonial musical activities in Brazil were largely overseen by lay brotherhoods, or irmandades. Organized along lines of class and race, irmandades existed for each sector of Brazilian society and they had tremendous influence. They built churches and hospitals, maintained clergy, oversaw funerals and feast days, and supplied music. Within cities and regions, irmandades competed to have the highest quality music, engaging in bidding wars for musicians and composers.

The southern mining region of Minas Gerais became an important site for musical activities after colonists found gold there in the late seventeenth century. Far from other sites of musical production, such as the Salvador (capital of Brazil from 1549-1763) and Recife, Minas Gerais provides a powerful example of the connection between local economic production and the culture industry. The gold rush led to rapid population growth and colonizers brought African slaves to work in the mines, joining a population that included Amerindians and mestizos. By the middle of the eighteenth century, black and mixed-race inhabitants formed the majority of the population, some enslaved and others free. The makeup of the irmandades reflected the demographics of the population, with individual brotherhoods representing distinct groups. Some irmandades, particularly those with mixed-race membership, became strongly associated with music making. In spite of restrictions that limited advanced study in composition to white students, nearly all of the prominent composers of the region were mulato, a phenomenon that has been termed mulatismo musical. There has been considerable scholarly debate in recent years surrounding the reasons behind the racialization of professional music making in colonial Brazilian society. Much work remains to be done, but it seems clear that the rise of a musical artisan class offered new opportunities for black and mulato musicians whose access to other forms of economic advancement had previously been restricted.

The wealth generated in the mines financed a musical boom in Lisbon that rebounded to Minas Gerais. Local composers imported and reinterpreted the mix of Portuguese and Italian Baroque and pre-classical musical styles enjoyed by the Portuguese court. They saw their works performed in ornate churches and theaters and on newly imported instruments, including a Schnitger pipe organ bought in 1752 that survives to this day. (See Figure 2.8)

Financed by its new material wealth, Minas Gerais produced an incredible amount of music and supported almost a thousand active musicians from 1760-1800. Among the most prominent was José Joaquim Emerico Lôbo de Mesquita (1746-1805). The son of a Portuguese colonist and an Afro-Brazilian slave, Lôbo de Mesquita was, like most Brazilian composers of African descent, largely self-taught. Renowned as an organ virtuoso and improviser as well as a composer, he contracted his services to various irmandades in the region. In 1801 he moved to Rio de Janeiro where he worked as a chapel organist.

Lôbo de Mesquita’s surviving compositions include two masses, a Te Deum, a Salve Regina, several motets and litanies, and music for the Office of the Dead. His music reflects the hybrid style that typified music in eighteenth-century Minas Gerais, blending baroque and galant elements. His Salve Regina, for example, owes a debt to the Neapolitan composer Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, whose compositions were popular in Lisbon and who had himself composed a Salve Regina which bears an uncanny resemblance to Lôbo de Mesquita’s later composition. Lôbo de Mesquita stretches this Neapolitan model, however, using a four-part chorus to interact with his emotive setting for solo voices. The piece is constructed of relatively short, contrasting sections. This concertato style looks back to established baroque practice, while the independent colors and textures in the orchestra reflect an awareness of contemporary European trends. The variety in this short piece is striking; Lôbo de Mesquita even includes a self-contained, “mini-aria” for soprano in the middle.

Rio de Janeiro (capital of Brazil from 1763-1889) produced the most celebrated composer of colonial Brazil: José Mauricio Nunes Garcia (1767-1830). Little is known about Nunes Garcia’s early life and musical training. The son of free, mixed-race parents, he was born in Rio de Janeiro shortly after the capital shifted to that city. A gifted boy soprano, Nunes Garcia participated in the city’s most influential musical irmandades and he joined the priesthood in 1792. Six years later, at the age of 31, he became chapelmaster of the Rio de Janeiro cathedral, the most prominent musical appointment in the city. As chapelmaster, he not only composed and played the organ, but also served as music director, impresario, and music teacher. Nunes Garcia’s career took an unexpected turn in 1808, when the arrival of the Portuguese royal family transformed Rio de Janeiro from the capital city of a colonial outpost to the epicenter of a thriving Portuguese empire. The Portuguese Prince Regent, Dom João, strongly supported music and upon discovering the gifted composer immediately appointed him director of the Royal Chapel.

Nunes Garcia composed prolifically. Over two hundred and thirty of his works survive, including sacred repertoire, instrumental compositions, and secular songs. His music is marked by its eclectic style, blending elements the innovations of Italian composers like Rossini and the classical-era approaches of composers like Mozart, Haydn, and Cherubini. He was followed the music of his European contemporaries and even conducted the first performance in Brazil of Mozart’s Requiem in 1819. Most of his sacred works are written for four-part chorus (with or without soloists) and orchestral accompaniment. His appointment to the Royal Chapel allowed him to expand the orchestra, and he regularly wrote for strings, paired woodwinds, trumpets, and occasionally trombone or timpani. He composed at least thirty-two masses, nineteen of which survive. The Missa de Nossa Senhora da Conceição (Mass of our Lady of Immaculate Conception, 1810) demonstrates his hybrid style. The example included here, a performance by the University of Texas Chamber Singers, records the first performance of the Missa in over two hundred years! In 1998, a young Brazilian musicologist named Ricardo Bernardes found parts of the manuscript for the Missa and he created a performance edition of the work, often having to deduce what Nunes Garcia would have done and fill in missing instrumental parts. Bernades went on to pursue a doctorate at the University of Texas and it is his performance edition that the University of Texas used for this performance. In the example, you’ll hear the “Cum sancto spiritu” that occurs near the end of the Gloria portion of the Mass. The text is set twice, first with soloists in a “modern,” classical style and then in a full choral fugue that recalls an earlier Baroque style. Nunes Garcia uses this two-part approach to set this text in several of his masses.

Not all colonial-era religious music was liturgical in nature, allowing the musical evangelization of the New World to spill out of the cathedrals. Urban streets became a site where people from different social, linguistic, and racial groups saw and heard each other, literally and figuratively. To the Spanish, religious processions offered an opportunity to witness the fruits of colonization: repurposed precolonial buildings, newly built colonial architecture and a society organized on a European model. For the colonized, processions reinforced this new order; their journeys through civic space highlighted the new sites of political and religious power: the Cathedral, the cabildo (town hall), and military fortifications.

Across Latin America, processions constituted a major component of Corpus Christi, an important religious and civic holiday. Established by Church officials in the fourteenth century as an obligatory feast affirming the central Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation (the belief that the sacred host used in the reenactment of the Eucharist was the literal body of Christ), the feast took place on the ninth Thursday after Easter. Following the expulsion of the Moors from Spain, the Spanish celebration of Corpus Christi took on a decidedly martial tone, with those who celebrated the feast characterized as victors, and those that did not (such as the Moors) characterized as vanquished enemies. In 1551, the Council of Trent declared Corpus Christi a “triumph over heresy,” and it became common in Spanish towns and villages for processions to take place with the host—the Body of Christ—carried through the streets. Processions tended to be elaborate, with music and dance, banners and tapestries, and all sorts of civic pageantry.

These themes of victory, vanquishing, and proselytizing resonated strongly with the colonial project, and Corpus Christi quickly became one of the most important festivals in Latin America. The Peruvian city of Cuzco held particularly lavish festivities. Visitors described the visual impact of indigenous costumes, the city’s ornate architecture, the procession of residents from parishes both within and outside of the city, each group holding the statue of its patron saint. “The entire course of the procession is a continuous altar,” remarked an eighteenth-century observer, noting the church officials who stopped to pray at designated sites. Written sources suggest that Church officials processed to the singing of chant alone, but paintings show native musicians accompanying them on “loud” wind instruments (Fig. 2.10). Other paintings show musicians singing while holding sheets of music, suggesting that they are performing polyphony. Indigenous performers not only played European instruments, they also marked the festivities with displays of indigenous culture, singing in distinct languages and playing traditional flutes, conch shells, and drums.

Corpus Christi coincided roughly with the Inca festival of Inti Raymi, the “Festival of the Sun,” and early observers suggested a conscious conflation of the two events on the part of Spanish colonizers. It is unclear how the Inca perceived Corpus Christi, but for church officials it came to represent the triumph of Christianity over indigenous religion. The fact that Cuzco had been the capital of the Inca empire made the festivities even more significant in this sense. In Cuzco, the pageantry of Corpus Christi enacted the defeat of Inca rulers at the hand of the Spanish. The presence of both native and European powerfully symbolized the shift from an old world order to a new. Although Spanish authorities made the training of indigenous musicians in European music a central strategy, they simultaneously required the performance of some indigenous music at civic celebrations. Thus, indigenous, “pagan” music could be gradually overcome and replaced by European sounds.

Similar rites took place elsewhere in Latin America. In Cuba in 1573, the Havana City Council ordered all free blacks to take part in the procession of Corpus Christi, bringing with them their “inventions and games,” referring to music and dance. Afro-Cubans did indeed participate, with some donning West African raffia masks of the íreme, or diablito (little devil), causing the festival in Cuba to become known as the Festival of Devils. The participation of Afro-Cubans, with drums, songs, and dances, added to the grandeur of Corpus Christi and contributed to the festival’s narrative of Christianity’s triumph over the infidels. The strength of this narrative may help to explain why the dominant Afro-Cuban festival was not Corpus Christi, but Kings Day, a carnivalesque holiday that momentarily inverted local power hierarcies, with high and low classes, slaves and slave owners symbolically performing the other’s identity.

In Brazil, as in other parts of Latin America, outdoor celebrations provided an environment where European musical aesthetics could commingle with African and Amerindian musics, giving rise to the development of hybrid forms. Churches, civic leaders, and irmandades hired musicians to perform at outdoor festivities such as Corpus Christi, bringing together formally trained musicians with those who performed popular music or played in military bands. Performers of double reed instruments, such as the shawm or chirimía (an ancestor of the oboe), along with the other loud wind instruments, performed together in raucous ensembles called charamelas that processed through the streets. Played by Afro-Brazilian musicians as well as by whites, the sounds of the charamela loudly proclaimed the cultural mixing that pervaded colonial Brazil

Missionary activities not only accompanied the conquest but continued to exert an important influence throughout the colonial period. Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries traveled to the far reaches of the Spanish empire to convert new souls to Christianity. Much of the mission music of the Jesuits in Bolivia and Paraguay or of the Franciscans in California is, like that of the earliest missionaries, designed to be utilitarian and accessible. At the same time, however, surviving repertories from both mission traditions illustrate that music could also dazzle the listener with sophistication; some of the most captivating music from the eighteenth century is found in these repertories.

Two important collections of music from South American missions survive, both of them in Bolivia. The first, held in Concepción, Bolivia, contains music from the mission churches of San Rafael and Santa Ana. A more recently discovered collection contains music manuscripts used by Jesuits who worked with the Moxos Indians. The variety of the music held in both collections is remarkable. Unaccompanied choral repertoire is present, but also vocal pieces with instrumental accompaniment, and pieces for instruments alone. Many of the compositions are the work of indigenous composers who wrote in a variety of native languages, including Guaraní, Moxa, Chiquitana, and Baure. Works by European composers also appear, as well as fourteen compositions by Domenico Zipoli (1688-1726), an Italian-born Jesuit who came to Argentina in 1717 and worked as the Cordoba chapelmaster until his death. His works became famous as far away as the viceroy of Peru.

Zipoli’s aria, “In te spero,” (Listening Example 2.6) is the central movement of the motet In hoc Mundo (On this Earth), written for tenor, two violins, and continuo. The work is a full-blown da capo aria in operatic style, complete with elaborate vocal coloratura that alternates with instrumental refrains, or ritornelli. “Da capo” translates as “from the head,” and the term is used for an aria with an A section followed by a contrasting B section (usually in a different tempo and another key), then a return of the A section. The aria offered ample opportunities for singers to display their skill, especially in the return of the A section, in which they embellished upon the written score. Here, the aria uses the full expressive possibilities of opera. Listen, for example, to how the dramatic denunciation of the “inimici” (enemies) contrasts with the tender expression of faith, “spero, in te confido,” at 0:49. Similarly, the staccato treatment of “non timebo naufragare” (I am not afraid of shipwreck) takes a device straight out of Italian comic opera: individual syllables set to short, staccato notes like this is a classic representation of fear, timidity, or even sneakiness. Zipoli uses this device to suggest that in the face of strong faith, fear is laughable when he contrasts that articulation against a strong and aggressive delivery of the same text. In the guide below, repetitions of the A-section text are printed in italics to aid your listening comprehension

The legacy of the Spanish colonial period is evident to anyone who has spent time in the southwestern United States, and is particularly visible in the string of missions that dot the West Coast. In 1767, Franciscan friar Junípero Serra set out from Mexico City on an evangelical enterprise; it brought him first to the missions in Baja California and then to San Diego in 1769, where he helped found twenty-one new missions extending up the coast of what the Spanish called Alta California. Serra’s endeavors coincided with King Carlos III’s expulsion of the Jesuits from the Spanish Empire and a general reduction of the influence of Rome within Spain and its territories. The Crown feared that increasing Russian exploration of North America might imperil Spain’s claim to its west coast holdings (extending up to what is now southeast Alaska) and he ordered the immediate colonization of the previously ignored territories.

California’s mission history and the role played by Serra and other friars has frequently been a source of controversy. Serra remains well-known in California. His statue stands in Golden Gate park and generations of school children learned of the hardships that missionaries faced in their efforts to “civilize” the new territory. In recent decades, however, the Vatican’s decision in 1987 to beatify Serra led to angry protests by Native Americans, who pointed to the decimation and maltreatment of Native Americans populations following the arrival of the Spanish.

For many years, scholars believed that music-making served a merely pedagogical and rudimentary function. However, John Koegel’s 1992 (re)discovery of manuscripts of complex polyphonic works, including three Masses (at least two have been attributed to Mexico City choirmaster Ignacio Jerusalem) offers compelling evidence of the highly-skilled performances that took place in California. Such evidence corroborates reports by eighteenth- and nineteenth-century visitors who commented on the high quality of the music making there and on the skill of Native American instrumentalists and singers.

The training of Native American musicians in the latest European and European-style music remained an important part of the evangelical process. As in the early days of the conquest, many friars studied native language and culture and became fascinated by native musical practices. Juan Bautista Sancho, for example, a Mallorcan-born friar who came to the California Mission of San Antonio de Padua in 1804, eventually learned several Native American languages. He translated catechisms into local dialect. In written documents Sancho not only describes the neophytes’ skill at learning European instruments and musical practices, he also comments on their own music, noting the presence of an open-ended flute and a one-string musical bow. His description of contemporary Native American singing is especially valuable, as it provides more details than those left to us by earlier missionaries.

They have many songs to sing in their dances, and outside of them as well […] they sing using various final pitches and with different scales; they rise and fall in intervals of seconds, thirds, fourths, fifths, and octaves; and they never sing polyphonically, and when they do sing all together some of them sing an octave above.

At the Mission of San Antonio, Sancho directed a large choir and orchestra, and introduced compositions from both Europe and New Spain, many of which he had copied himself and brought with him. The Jerusalem Masses, discussed previously, may have been among these works. He composed Masses himself, as well as polyphonic arrangements of plainchant.

Understanding the role of mission music in “Alta California” not only helps us to understand the artistic and cultural history of New Spain; it also enriches our understanding of the cultural heritage of what later came to be the United States. That such a musical infrastructure existed in California at the end of the eighteenth century is remarkable when one considers the still rather rustic cultural conditions that existed in the fledgling British colonies far to the east. Recognizing colonial California’s musical culture forces us to expand our historical understanding of the United States to include Hispanic, as well as English, cultural heritage.

In Spain, Philip IV’s ascension to the throne in 1621 transformed the role of the arts in Spanish society, ushering in a new “Golden Age” of theater, music, and art. Although opera swept across Europe during that same period, the Italian style of recitative (dialogue sung in a speech-like manner) and aria (more elaborate and melodic songs) did not have much immediate influence. Spanish composers and audiences instead preferred zarzuelas: Spanish-language, sung dramas that fused chains of strophic songs, allegorical plots, and dance with spoken dialogue. In the second half of the seventeenth century, however, composers and librettists revisited the idea of opera, experimenting with recitative, and merging elements of the newer Italianate style with more traditionally Spanish sensibilities. Staged musical dramas debuted in the musical landscape of the Viceroyalty of Peru as early as 1672, with a performance of El arco de Noé (Noah’s Ark). It included elaborate stage machinery, scene changes, costumes, and lighting. Sponsored by the Viceroy himself, the musical spectacle was a huge success.

The first opera composed in Latin America was Tomás de Torrejón y Velasco’s La púrpura de la rosa, premiered in Lima in 1701. Based on Pedro Calderón de la Barca’s 1659 libretto, it commemorated the Peace of the Pyrenees between Spain and France and Spanish composer Juan Hidalgo had already set the text in 1660 in one of the first successful and well-received Spanish operas. Torrejón y Velasco’s setting celebrated the birthday of Philip V, the first Bourbon king of Spain. In his version of La púrpura de la rosa, the author avoids recitative, instead structuring the opera around chains of strophic songs over a spare continuo (accompaniment) of harp, guitar, and percussion. Focusing on Ovid’s amorous tale of Venus and Adonis, the opera features well-known characters from Greek mythology in a morality drama that stresses prudence and reason over emotion. Groups of professional female actresses typically performed dramas such as this; the only male roles in Torrejón y Velasco’s score are for the villano (ruffian) and the role of Chato, both comic, lower-class (and lower-voiced) male characters.

While the musical form and texture are relatively simple, the composer achieves tremendous expressive variety in setting Calderón’s text, bringing out the libretto’s erotic tension through suggestive dance rhythms, insistent repetitions, and expressive ornamentation and vocal dissonances. The music might seem tame to modern ears, but some present at the 1701 Lima production protested the “immorality” of the amorous plot as well as some of its Enlightenment-oriented ideas. These included having the wives in the audience sit in chairs next to their husbands rather than on pillows at their feet!

In the excerpt included here, Adonis (written for a soprano, but here sung by tenor Mark Tucker) details to Venus the contents of a rather erotic dream from which he has just awoken. After a brief introduction in which Adonis says that images keep reappearing in his dreams, the music engages in a kind of circular repetition, much like a dream from which one can’t awake. Each poetic copla is set to the same melodic formula, but the music changes subtly. Notice, for example, how the run on “fiero” (fierce) dramatizes the attack of the wild boar, and how the singer’s expressive pauses when discussing blood staining the white roses seem to stop time and turn the tale from one of action to one of sensory experience.

Not to be outdone by the Peruvian Viceroyalty’s achievements in operatic entertainment, the newly appointed Viceroy of Mexico commissioned Manuel Sumaya (1678-1755), then a musician in the Mexico City cathedral (he would become chapelmaster there in 1715), to write an opera. Sumaya composed his Parténope (1711) on a translation of an Italian operatic libretto by Silvio Stampiglia, making it the first opera to be composed by a New World composer. Sadly, the music does not survive. It would be nearly a century before Brazil saw the composition of its first opera, Le Due Gemelle (composed sometime between 1813 and 1821, also lost). Although European opera maintained its dominance over Latin America throughout the colonial period, Torrejón y Velasco’s and Sumaya’s compositions stand out as important developments, followed by the emergence of regional and national operatic styles in later centuries.

Dance flourished at every level of Latin American colonial society. From the stately and refined figure dances popular in aristocratic circles to the more boisterous and physical mestizo bailes, dance music enjoyed popularity across the continent, with many local styles making their way back to Europe. Professional guitarists, harpists, and violinists formed the core ensemble of colonial dance music, although hand percussion such as tambourines, palmas (hand clapping), or castanets might also be heard.

While both written and iconic sources attest to the prominent role musical entertainment played in the New World, know less about the repertoire and its performance practice than we do about music written for religious purposes. This is because secular music-making was primarily an oral tradition. Tunes passed from performer to performer and skilled players and singers improvised melodic and rhythmic variations on existing melodies and newly composed themes alike. Thus understanding what dance music and other secular musical entertainment sounded like requires a fair amount of musicological detective work. The primary sources of colonial-era dance music available to us today are two publications for guitar and harp by Santiago de Murcia and Lucas Ruiz de Ribayaz, Spaniards who traveled to the Americas, along with their music. The books include popular tunes of the day, and since the voyages of Ruiz de Ribayaz (who arrived in Lima in 1667) and Murcia (believed to have arrived in Mexico sometime after 1717) fell fifty years apart, they provide a glimpse into the development of popular music over several decades. Murcia’s source book came to the notice of music scholars by chance. In 1943, Gabriel Saldívar, one of Mexico’s earliest musicologists, found the manuscript (now referred to as the Saldívar Codex) in an antique shop in Guanajuato. Recognizing its value, he spent much of his remaining life uncovering its secrets.

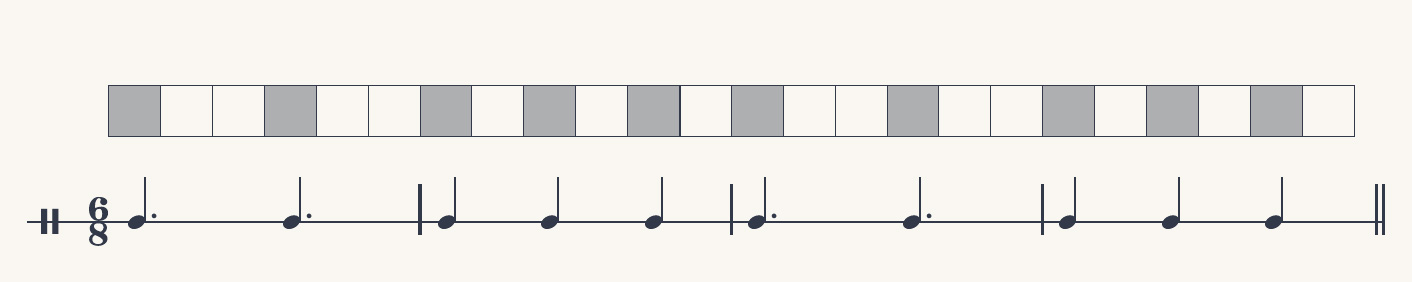

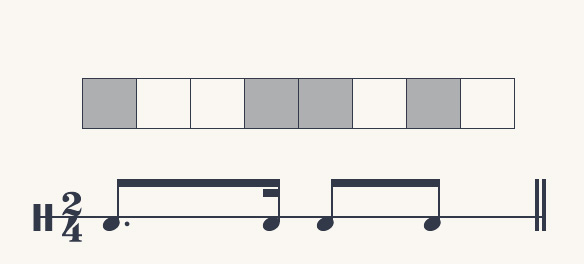

The jácara (xácara) was one of the most popular dances of the Baroque period. A boisterous baile that had its origin in Spanish theater, (the jácaro was a stock character, a ruffian or a trickster), the jácara developed on both sides of the Atlantic. It is recognizable by its emphasis on the minor mode and its alternation of two primary harmonies, such as D minor and A major, and by its incessant and energizing hemiola pattern: 1-2-3, 4-5-6 | 1-2, 3-4, 5-6 |1-2-3, 4-5-6 | 1-2, 3-4, 5-6 |, which can be seen notated in Ex. 2.2

This jácara rhythm is found in many forms of music besides dance music, such as the villancico genre, where it referenced popular culture. “A la xácara, xacarilla,” by Juan Gutiérrez de Padilla is an example of just such a fusion. The villancico seems to goad the musicians on, suggesting that joyful dance is the only appropriate response to the Christmas story, calling out, “¡Vaya de xácara!” (On with the jácara!) Not only does Gutiérrez de Padilla engage with dance rhythms, but the work’s text is a medley of sorts, with each stanza containing the first line of a popular romance, or secular poem, that would have been well known to contemporary listeners. Thus, while the subject of the villancico is ostensibly sacred (the birth of the Christ Child), its delivery is highly secular.