Mexico’s history and musical traditions are among the richest and most varied in Latin America. Mexico is the second-largest Latin American country, after Brazil, with more than 130 million inhabitants. Its capital, Mexico City, has become one of the largest cities in the world. Migration within Mexico from the countryside to the cities accelerated greatly in the twentieth century, and about 80 percent of the population now lives in urban areas. As in the case of other Latin American countries, Mexican music draws heavily from its rural past, yet increasingly dialogues with modern, international influences. One of the most dynamic areas of musical experimentation in recent years has occurred in the northern region bordering the United States, and new forms of music have developed there, as well as among Mexican Americans living in states such as California, Illinois, and Texas.

Mexico is a land of great geographic diversity. Its total physical area is about 12.5 million square miles, and its two main mountain ranges divide the country north to south. Images of the two imposing volcanos in the vicinity of Mexico City (Iztaccíhuatl and Popocatépetl) have long served as symbols of national pride. The narrowest point in the mainland part of the country is the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, long a trade route linking the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific. The almost eight-hundred-mile-long Baja California peninsula is separated from most of mainland Mexico by the Gulf of California.

Mexico has a very sizable Indigenous population with its own unique languages—more than 60 of them, including Náhuatl, Maya, Tzotzil, Mixtec, Zapotec, Otomí, and others—and many cultural forms, with the largest concentration of Indigenous Mexicans in the southern states. The United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean estimates that about 20 percent of Mexico’s population is of Indigenous heritage. Entire civilizations rose and fell prior to the European conquest; the cultural legacies of groups such as the Olmecs, Toltecs, Mayas, and Aztecs warrant independent investigation on your part. Many important figures of Mexico’s past have been of Indigenous ancestry, including president Benito Juárez, revolutionary war hero Emiliano Zapata, and composer Juventino Rosas. In recent decades, Indigenous uprisings in Chiapas and elsewhere led by the ELZN (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional/the Zapatista Army of National Liberation) have made international headlines. Mexican politicians and cultural leaders, and Indigenous groups themselves, have struggled for many years to integrate local influences fully into national culture, overcoming biases against such heritages inherited from the colonial period.

The largest part of the Mexican population today is of mestizo or mixed-race ancestry, in this case primarily Indigenous and Spanish, with some African and other influences. Most styles of traditional Mexican music can be considered mestizo, in that they combine elements of European, Indigenous, and African heritage, as well as transnational influences. The term mestizo originated in the colonial period as part of the casta or caste system employed during Spanish colonial control. Under this system, mixed-race individuals had more legal rights than Africans or native peoples, but considerably fewer rights than Spaniards and their descendants (known as criollos or creoles). It is important to consider that citizenship was granted to Mexico’s Indigenous peoples long before it was granted to their counterparts in the United States. In Mexico and elsewhere, the notion of mestizo-ness or mestizaje initially had negative associations, but became central to a new national identity as the country struggled for independence from Spain in the early nineteenth century.

Mexico is intricately bound to the United States by history, geography, and through immigration; and the two countries share a two-thousand-mile border. The states of California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, and parts of Colorado and Utah once belonged to Mexico, and Mexican cultural traditions are strongly represented there today. Individuals of Mexican heritage constitute the largest U.S. Latino/a group by far. Continued difficult economic conditions force many Mexicans north in search of better opportunities, and Mexican settlement in the United States has expanded in recent decades to include the Southeast, Chicago, the Northeast, and elsewhere. California continues to have the largest Latino population in the United States, and Los Angeles County is now the second-largest Mexican metropolitan area in the world after Mexico City.

Mexico’s contact with the European world began in 1519, the year Spanish conquistadores arrived and began to colonize the region. Having encountered primarily small groups of native peoples previously, the Spanish found to their amazement that large, urban civilization existed in central Mexico and in the Mayan Yucatán peninsula, with expertise in architecture, astronomy, a system of pictographic writing, and libraries. The Aztec Empire, with a population of hundreds of thousands, extended from coast to coast and south into what is now Central America; its capital, Tenochtitlán, ranked among the largest cities in the world at the time (see Chapters 1 and 2). At first unsuccessful in their attempt to conquer the region, the Spanish returned and subdued the Aztec forces with firearms in 1521. The capture of Tenochtitlán marked the beginning of a three-hundred-year-long colonial period in which what is now Mexico and large parts of the southwestern United States became part of “Nueva España” or New Spain. Spanish authorities burned Aztec documents and killed members of the educated classes, making it difficult to reconstruct their social and cultural life in detail today. After conquest, European-styled cities were established throughout central Mexico, some on the sites of Indigenous settlements that existed long before the arrival of the Spanish, including Mexico City, Puebla, Guadalajara, Valladolid (now known as Morelia), Oaxaca, Durango, and Veracruz. Cathedrals were established in many colonial cities, and parish churches were built in towns and villages throughout New Spain. Music for religious services was given an important role in the ceremonial life of both the parish church and cathedral.

Political unrest in the early nineteenth century led to independence movements in many Spanish colonies in the Americas. On September 16, 1810, the priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla (1753–1811) declared Mexican independence in the small town of Dolores (now the city of Dolores Hidalgo in the state of Guanajuato). The struggle for an independent Mexico lasted 11 years, concluding in 1821 when General Agustín Iturbide declared himself emperor of newly independent Mexico. Ongoing political upheaval followed as different political factions vied for power. General Antonio López de Santa Anna, one of the dominant figures of the period, served as president numerous times between 1833 and 1855. His attempt to keep Texas as part of Mexico failed when his forces surrendered to those of Sam Houston in 1836; in 1845 the United States annexed the independent Texas Republic (1836–1845). The U.S. victory in the Mexican-American War of 1846 to 1848—instigated by President James Polk under the aegis of U.S. expansionism—resulted in the forced cession of a large portion of Mexican territory (now the states of California, Arizona, Colorado, Utah, and New Mexico) to the United States.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, Mexico experimented with monarchical, federal, and centralized forms of government; liberal, moderate, and conservative factions alternated in power. In the second half of the nineteenth century, new conflicts developed that challenged the fledgling Mexican nation. Attempts to reign in the far-reaching power of the Catholic Church led to a civil war known as the War of Reform (1857–1861). Victory by liberal forces in this conflict led in 1861 to the first presidency of Benito Juárez (1806–1872) and the confiscation of church property. Juárez suspended Mexico’s foreign debt payments that year because of an economic crisis, angering European creditor nations. Shortly thereafter, French military intervention forced Juárez from Mexico City and led to the crowning in 1864 of a new magnate, the Austrian Hapsburg Archduke Maximilian (1832–1867), as Mexican emperor Maximilian I. He retained the throne for four years, but eventually lost in battle to Juárez’s forces, was captured, and executed in the city of Querétaro. Juárez then resumed the presidency, through the 1870s.

Political tranquility generally reigned during the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz (1830–1915), a military leader who forcibly took over the government in 1876 and ruled the country imperiously for many years, serving as president from 1876 to 1880 and 1884 to 1911. Under Díaz, foreign investment supported rapid growth in the country’s infrastructure. Many beautiful European-style civic buildings date from this period; the railroad expanded significantly; communication throughout the country improved greatly; and trade increased. But this period of industrialization carried a high social cost as many people continued to suffer severe poverty. Large numbers of disenfranchised rural campesinos (peasants), many illiterate and of Indigenous heritage, served the interests of a relatively small number of wealthy hacendados (large property owners). Large disparities of wealth existed between the urban elite and middle classes and the rural population. All of this, in combination with a lack of democratic rule, led to political unrest and ultimately armed rebellion.

The Mexican Revolution of 1910 to 1920 resulted from these inequities and radically changed Mexican society. In its aftermath, the government broke up many haciendas (large rural properties) and redistributed the lands to individuals and communities. The 1920s and 1930s also brought a flowering of the arts. The Mexican mural painting movement, supported by the government and headed by artists such as Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, celebrated Mexican Indigenous culture consistently for the first time, as well as the heroes of the Mexican Revolution. Artists of the period attempted to symbolically unify a country heavily divided along lines of class and ethnicity and whose leadership had never come to terms with the country’s Indigenous heritage.

The Mexican film industry gained international stature from the 1930s, and Mexican entrepreneurs established radio stations throughout the country. Both film and radio had a tremendous influence on national and international music making. Mexico City’s XEW, “La Voz de la América Latina” (The Voice of Latin America)—broadcasting first in 1930 and featuring prominent musicians such as Agustín Lara—became one of the most influential radio stations in the western hemisphere. After suffering through the Great Depression, Mexican society rebounded during the 1940s and the post–World War II economic boom, in no small part due to the nationalization of Mexico’s large oil reserves. This prosperity ushered in a “golden age” of Mexican film that lasted through the early 1960s. Musical films from this period achieved broad international popularity, and contributed to the popularization of mariachi repertoire, as well as the bolero, mambo, chachacha, and other popular music genres.

Social and political trends in more recent decades have continued to shape Mexico’s cultural life. The rapid growth of Mexico City and its larger metropolitan area of about 22 million, now home to nearly a third of the country’s population, has made it central to musical life. And yet, as northern states such as Baja California, Sonora, Sinaloa, Chihuahua, and Nuevo León have become important as conduits of trade with the United States, they have influenced the rest of the nation musically as well, especially with the musical genres of banda sinaloense and música norteña. The strong influence of popular culture from the United States and Europe has led to the emergence of a vibrant rock scene in Mexico. NAFTA, the North American Free Trade Agreement, implemented in 1994, has not been a resounding success, especially for communities reliant on agriculture for their sustenance; agricultural products imported from abroad without tariffs have had a negative impact on Mexican farmers. The assertion of Indigenous rights continues to take many forms, and immigration from Mexico to the United States remains a topic of urgency and politization on both sides of the border, as does the war against drug trafficking.

Indigenous Mexican communities have been able to maintain many unique traditions because they have adapted to changing circumstances, despite forced servitude, the devasting effects of imported European diseases, land expropriation, and social and political marginalization. Despite significant efforts to integrate Indigenous groups into the nation in recent decades, they often remain socially disadvantaged. The states with the largest Indigenous representation include Oaxaca, Chiapas, Veracruz, Yucatán, Puebla, and the area around Mexico City. Each of the scores of distinct Indigenous groups has its own rich music and dance traditions; countless styles of music are performed in these communities, making it difficult to characterize the repertoire in general. However, the music of various Indigenous communities does share common functions, especially music for entertainment and for ritual celebrations: marriages, wakes and funerals, fiestas for locally venerated Catholic saints, and other commemorations.

Important efforts have been made to preserve and study Indigenous music, culture, and languages in recent decades, and local and national governmental patronage supports a wide range of projects: the teaching of native culture and history in schools; bilingual education; radio programs in Zapotec, Mixtec, and other Indigenous languages; research and publications on Indigenous topics and history; competitions for the best literature in Indigenous languages; subsidies for native wind bands and other musical ensembles, and so on.

Some Mexican Indigenous music sounds very different from Western music, while other pieces sound modern and cosmopolitan; many blend newer and older influences. Few documented examples of Indigenous music as performed before European colonization exist today, however. Most native communities have adopted at least some European-derived instruments (violins, guitars, harps, etc.), often altering their construction, tuning, or performance practice in some way. Indigenous groups also perform well-known genres including the son (discussed below) and form ensembles such as wind bands, as do other segments of the population. Much native Mexican music is instrumental, performed on drums or other percussion instruments such as rattles or shells, and flutes. As in the case of U.S. Indigenous traditions, dance and movement, as well as the use of masks or costumes, are often closely linked to music-making; ceremonial performances often enact beliefs and legends about the supernatural world. This is certainly true of some of Mexico’s more spectacular Indigenous musical traditions such as the performances by the Totonac voladores of Papantla (Wiki) from the state of Veracruz (see Figure 3.2). The four fliers (“bird men”) launch themselves from the top of a high pole and descend slowly circling the pole with their feet attached to the pole by a rope. They represent the four cardinal directions and the four elements of earth, air, fire, and water; their descent is accompanied the music of a pipe and drum played by the caporal, who stands on the top of the pole.

The southern state of Oaxaca, with the largest number of native peoples, had an advanced civilization well before European contact, as evidenced by the archeological sites at Monte Albán and Mitla. Many leading figures in Mexican history have come from the state, including presidents Benito Juárez and Porfirio Díaz, and the artist Rufino Tamayo. The dominant native languages spoken there are Zapotec and Mixtec. Oaxaca is also known for its many other contributions to Mexican culture: piquant moles (flavorful sauces made of ground spices) and other regional foods, colorful Indigenous dresses for women, local fiestas (especially the Guelaguetza ceremonies with wind band concerts in Oaxaca City),and the dominance of women in market life in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

“Huistan, Fiesta of San Miguel, 1974. Three Drums and Small Flute” (Listening Guide 3.1) comes from the neighboring southern state of Chiapas, where most communities are Maya descendants. The piece was recorded in the 1970s and performed by the Huistan people—known for their resistance to external cultural influences—during a festival for a patron saint. Many of their musical forms (including this one) are associated with folk Catholicism, the blending of Catholic and Indigenous practices. A three-hole cane flute provides the principal melody in the example, accompanied by several single-headed drums played with sticks. Note the recurrent rhythmic pattern supporting the principal melody, a characteristic of much Indigenous repertoire, as well as the melodic ornamentation, the constant improvisation or variation of melodic themes, and the subtle differences between the pitches used and those characteristic of Western music. Listening Guide 3.1 provides some feel for contemporary Indigenous musical aesthetics, although such practices continue to change. Even many of the “traditional” flutes and drums used by the Huistan and others are patterned after European instruments brought to the Americas centuries ago rather than those used before the conquest.

In depth

More than a fourth of the population of the southern state of Chiapas identifies as Indigenous. The largest groups include the Tzeltales, Tzotziles, Choles, and Zoques, while the region surrounding the famous town of San Juan Chamula, Chiapas, has a predominantly Tzotzil Maya-speaking population. Located at an elevation above 7,200 feet, the town of San Juan Chamula is a popular tourist destination because of the beauty of its surroundings and its colorful celebrations, especially during carnival season and the feasts of San Juan Bautista (Saint John the Baptist, after whom the town is named) between June 24 and 26, San Sebastián, and Santa Rosa. Local handicrafts include woven textiles and various forms of folk art. Residents of San Juan Chamula have a long history of resistance to outside governmental authority. The area was a site for the Tzeltal Rebellion of 1712 to 1715 and the Guerra de las Castas (War of the Castes) of 1869. In the 1990s, it was a center of Zapatista guerrilla activity.

The church of San Juan Chamula vividly demonstrates the syncretic approach local Indigenous peoples take towards Catholic ritual and Maya religious beliefs. The Tzotziles come as families and in other small groups at all hours, light candles on the floor covered in pine needles, and recite prayers in Tzotzil that move between song and repeated recitational phrases. Catholic saints are venerated alongside Indigenous religious symbols, showing how conversion to Catholicism was far from complete here. Musicians play harps and other forms of music outside the church door on important feast days. Although the area is predominantly Catholic, evangelical Protestant groups have gained converts in recent years, creating conflict with local community leaders, who seek to maintain their authority and general adherence to traditional religious beliefs.

In addition to Indigenous vocal and instrumental music, especially on marimbas, many different styles are heard in the area: rock, accordion-based música norteña from northern Mexico, and other popular genres. The town of San Juan Chamula is also noted as a center for the manufacture of musical instruments, especially harps and violins. The rock fusion group Sak Tzevul (meaning “lightening”), founded in the 1990s, comes from Zinacantán, Chiapas, near San Juan Chamula. It performs throughout Mexico and Central America and releases innovative commercial recordings. Leader Damián Martínez (singer, guitarist, composer) and other band members sing in Tzotzil, Spanish, and other languages, and describe their music as música tradicional/progresivo (traditional/progressive music).

Though Indigenous music like that in “Huistan, Fiesta of San Miguel, 1974. Three Drums and Small Flute” (Listening Guide 3.1) can be characterized as traditional, most Mexican music straddles the boundary between traditional and popular. Through the mid-twentieth century, Mexico remained a relatively rural society with countless musical forms rooted in local communities. Today the situation has changed. Traditional forms persist, yet have been transformed through performance in urban contexts, dissemination in the mass media, “folklorization” (being placed on stages in formal concert settings), and fusion with other national and international genres. Many forms of Mexican music constantly evoke the rural past stylistically or lyrically, but are equally tied to modern urban experience.

Listen to the CD Tzotziles: Psalms, Stories, and Music (Sub Rosa SR17) for traditional syncretic ceremonial music of the Tzotziles. Listen to Indigenous Mexican music on the Smithsonian Folkways website, and compare this music with modern commercial releases by Sak Tzevul or artists such as Lila Downs, a mixed-race performer from Oaxaca who records frequently in Indigenous Mexican languages.

Traditional Dance Repertoire

Dance has been important to Mexican society for many centuries, and dance music is heavily represented in its traditional repertoire, both mestizo and Indigenous. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, common European and Spanish dances included the contradanza (contradance), minuet, boleras (not the later popular song type of the bolero), waltz, mazurka, schottische, and polka. Ensembles made up of strings and wind instruments, or of various combinations of harp, guitar (and various guitar types), violin, and piano supplied dance music. Earlier Spanish dance styles also included the zapateado (a dance that featured fancy heel work, rhythmic striking of the feet against the ground), fandango, and seguidilla. The Mexican jarabe was also very popular. Dance activities often attracted the attention of the Catholic Church, which at first condemned the jarabe and other popular genres because of their allegedly indecent nature (too much close physical contact, flirtation, bawdy lyrics, etc.). But such prohibitions never succeeded in stamping out these dances.

The Mexican jarabe consists of a series of different-but-connected short dance pieces played in succession as a single unit, often with contrasting tempos, rhythms, keys, and choreographies. Although small ensembles of harpists, violinists, and guitarists frequently performed the music of the early jarabe, larger groups such as mariachis continue to play it today. In the early twentieth century, the jarabe from the state of Jalisco, the jarabe tapatío (known in English as the “Mexican Hat Dance”), came to be viewed as representative of Mexican musical folklore on a national level. Elementary school children are taught to perform it today, along with other regional styles. And many Mexican classical composers have published arrangements, especially for piano, that preserve old jarabe melodies.

Typical individual sones (tunes) used in the jarabe include pieces such as “El atole” (a hot, sweet corn beverage), “El perico” (The Parakeet), “El durazno” (The Peach), and “Los enanos” (The Dwarfs), among numerous others. Some of these titles refer to the choreography used in the dance, especially those that imitate the subjects of the song titles. Some, such as “El durazno,” contain sexual or erotic double entendres or references. “El perico” plays on the sound of the repeated words “pica” (to peck) and “perico” (parakeet). It discusses birds as a metaphor for a young couple and is clearly intended to be flirtatious. “El atole” contrasts the sweetness of the beverage with the bitterness of the the atole seller; the song seems to suggest that she also needs to be “sampled” before she “goes bad.”

“El perico”

Pica, pica, pica, perico,

pica, pica, pica la rosa.

“The Parakeet”

Peck, peck, peck, parakeet,

Peck, peck, peck at the rose.

Quisiera ser periquito

para volar en el aire

y allí decirte secretos

sin que los oyera nadie.

I would like to be a parakeet

So that I could fly in the air

And tell you secrets there

Without anyone else hearing them.

“El atole”

Vengan a tomar atole

todos los que van pasando.

Que si el atole está bueno

la atolera se está agriando.

“The Atole”

Come and drink atole

All of you who are passing by.

For if the atole is good

The atole seller is becoming bitter.

De este atolito de leche

y tamales de manteca

todo el mundo aproveche

que por esto no se peca.

From this atole made of milk

And the tamales made with lard

Everyone benefits

Because this way no one sins.

References to animals, fruit, and flowers are common in the poetry of rural communities, and can be seen as anthropomorphized symbols of human activities, including courtship. Figure 3.3, Casimiro Castro’s mid-nineteenth-century lithograph El fandango, shows a couple dancing to the sound of traditional dances, such as the jarabe.

Dance participation is widespread in Mexico today and Mexicans eagerly embrace popular Mexican dance styles as well as reggaeton, salsa, and cumbia, which originated in other areas of Latin America, especially the trans-Caribbean region. They also create their own local versions of these Latin American dances. Other social dances such as the danzón (imported from Cuba) and European ballroom dancing are still practiced, especially in the state of Veracruz and in Mexico City.

One of the most important kinds of traditional Mexican music is the son. The term son is a cognate of the English word “song”; it can be used in a general sense by Spanish speakers in various countries to mean song or tune, but can also refer to specific regional or national styles of music. Mexican son styles are especially diverse: at least half a dozen distinct forms exist in individual areas, all with unique characteristics. The son jalisciense (Jalisco-style son) and the son huasteco or huapango from Veracruz are among the best-known subgenres, and are discussed below. Sones (the plural form of son) have become closely tied to national regional and national identities and representations of Mexico. They emerged as distinct musical forms by the eighteenth century, the result of fusions of influences from Spanish, Indigenous, and West African musical practices.

One example of a regional son variant is the son jarocho from the state of Veracruz, along the eastern coast of the Gulf of Mexico. Instruments in the jarocho ensemble typically include the arpa jarocha (Veracruz-style harp), various types of jarana (a small guitar), and the requinto (another guitar-like instrument), along with voices. The jarocho harp has between 32 and 36 strings, stands about five feet high, and plays all the diatonic notes in the key of the song, but cannot play chromatic notes because it does not have pedals to raise or lower the pitch of individual strings. A change to another key can require the retuning of the instrument. Considerable proficiency is needed to play the arpa jarocha, which provides a bass line (played by the left hand) and the chords and melody (played by the right hand). The typical jarana has frets and between eight and twelve strings arranged in five courses (sets or pairs of strings), usually three doubled courses and two single strings. The jarana is strummed and provides the chordal and rhythmic accompaniment. The requinto usually has four single strings, and is played with a pick. It provides melodic lines that complement those played on the harp.

Son jarocho repertory consists of regional sones from Veracruz as well as dances and songs from other parts of Mexico and from abroad. Those that are particularly associated with Veracruz and the son jarocho include lively dances with sung verses and that alternate between <3/4> and <6/8> meter. Well-known examples include “La bamba” (the most famous), “La iguana” (The Iguana), and “La guacamaya” (The Macaw), among many others. These are played and sung as dance music, or performed separately. They allow for vocal dialogues, with singers alternating verses back and forth, often improvising them as they go, to continuous instrumental accompaniment.

Jarocho dancers typically perform as couples on a raised wooden platform (tarima), creating a percussive effect with their rapid footwork. The women often dance, while the men sing and play. Famous son jarocho groups include the ensemble of Afro-Mexican jarocha harpist Graciana Silva, “La Negra Graciana” (Black Graciana), and, more recently, Tlen Huicani, Son de Madera, and Chuchumbé (this last group is named after the chuchumbé, an erotic dance banned by the Catholic Church). Son jarocho has made an impact outside its own world, with rock groups such as Cafe Tacuba and Los Lobos incorporating its sounds and instruments into their performances.

“La bruja” (The Witch) (Listening Guide 3.4), is a son jarocho with lyrics in the typical form of paired four-line stanzas. As described above, performers can freely change the order of the verses or improvise new ones. When this son is performed as a dance, it is customary for women to balance lit candles on their heads. The lyrics of “La bruja” present an image of a bewitching and beautiful woman who captures the attention of a man. The term jarochito sung in this song refers to a person from the gulf coast of Mexico in the state of Veracruz. Note that “La bruja” is performed in triple metre rhythm listen to examples of pieces such as “La iguana” (see links above) to compare “La bruja” with the up-tempo and syncopated pieces that feature prominently in son jarocho repertoire.

The corrido is one of the most enduring forms of Mexican song. It is both a traditional genre with a long history and an important part of contemporary commercial repertoire. Corridos are narrative ballads about particular people, groups, or events of social or historical importance. The stories they tell might have occurred in the past, or can be about current events. Common themes include the exploits of outlaws, revolutionaries, or military men; the extraordinary experiences of common people; and natural disasters or other newsworthy happenings. Corridos have been widely popular at least from the time of the Mexican Revolution of the 1910s. Many songs deal with conflicts along the U.S.-Mexico border, generally between English- and Spanish-speaking groups or individuals. Indeed, the history of the corrido is closely linked to the border, and scholars such as Américo Paredes have suggested that it first developed there rather than in central Mexico. One of the most famous of all corridos is “El corrido de Gregorio Cortéz,” about the conflict between Texas Mexicans and Anglo-American Texans at the turn of the twentieth century. (A film was released in 1982 about Cortéz’s life and struggle; see Further Viewing below.) The corrido today is as favored a musical genre among Mexican immigrants in the United States as it was a century ago, and many corridos have dealt with the mistreatment of immigrants by U.S. authorities, as well as the clash between cultures along or near the border. There is a sense of empathy in corridos for the oppressed individual who has become an outlaw or has been rejected as a result of political and social repression. A probable predecessor of the genre is the Spanish romance, a narrative ballad form that also told stories of heroic events or deeds, typically connected with the aristocracy.

Corrido texts usually consist of four-line stanzas, each line having eight syllables. The melodies to which they are sung are simple, easy to remember, and most often strophic in form (each stanza of text is sung to the same melody), which makes them easy to perform and to pass along from one community to the next. The harmonies used are also simple. Acoustic guitars traditionally accompany corridos, though full mariachis also perform them, as do música norteña groups (the northern Mexican accordion-based style) and other ensembles.

The CD set The Mexican Revolution (see Further Listening) contains many historic and more recent

recordings of corridos about the revolution. This also includes a very extensive program booklet with

lyrics and translations.

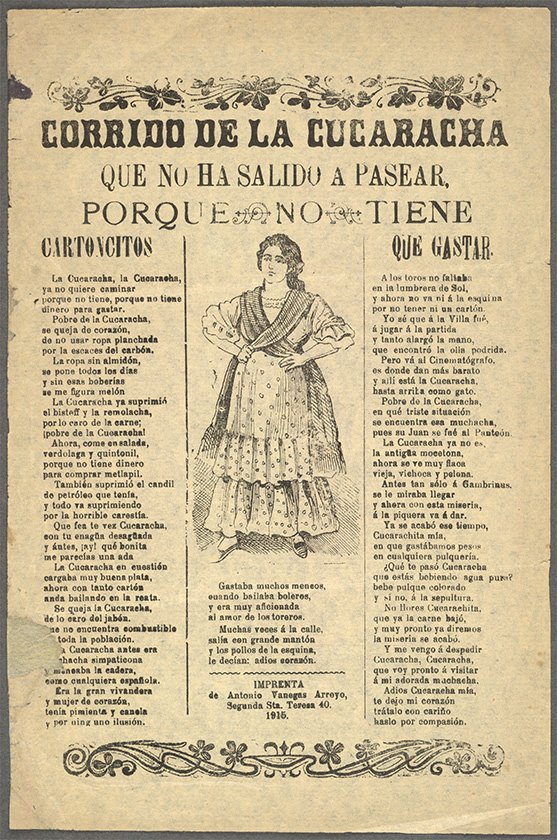

In the past, many corrido lyrics were sold as printed broadsides, single sheets of paper with striking images that illustrated the events described. Figure 3.5, “Corrido de la cucaracha” (Corrido of the Cockroach), presents a well-known piece from the 1910s with an image drawn by the famous artist José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913). The lyrics discuss general Francisco “Pancho” Villa (1877–1923), a central figure of the Mexican Revolution. Corridos have also been published as sheet music or in songbook collections without music notation known as cancioneros. Some of Mexico’s most famous popular singers, such as Lucha Reyes, Ana Gabriel, Vicente Fernández, and Juan Gabriel, and most popular bands, such as Los Tigres del Norte, have recorded corridos and have performed them live in their concerts..

Listening Guide 3.3 , “El Siete Leguas,” is a famous corrido written by Graciela Olmos (c. 1895–1962). It tells another story about Villa, who served as commander of the División del Norte (Northern Army Division) during the Mexican Revolution, and his favorite horse “El Siete Leguas” (Seven Leagues). Known as “la bandida” (the female bandit), Olmos reportedly served alongside Villa’s army as a soldadera (female camp follower). Her corrido “Siete Leguas” inspired a 1955 film of the same name about Pancho Villa, staring singer-actor Luis Aguilar.. A well-known brand of Mexican tequila was even named after Villa’s famous horse!

In depth

The corrido is a living musical form. As in the past, corrido composers today deal with themes of immediate interest to their public: immigration, social inequity, poverty, political corruption, and so on. The corrido has a journalistic purpose, and composer Paulino Vargas (d. 2010), accordionist of the group Los Broncos de Reynosa, believed that creators of this genre should be considered reporters, even if they sometimes exaggerate contemporary events. Corridos present a history from the popular viewpoint, not that of the official record. Vargas’s “Las mujeres de Juárez” (The Women of Juarez City), recorded by música norteña group Los Tigres del Norte on their 2004 Pacto de Sangre (Blood Pact) album, for instance, condemns the murder of innocent women in the northern border city, many of them factory workers: “Humillante y abusiva la intocable impunidad / los huesos en el desierto muestran la cruda verdad / las muertas de ciudad Juárez son vergüenza nacional” (Humiliating and abusive, the untouchable impunity [the government’s failure to act] / The bones in the desert show the raw truth / The dead women of Ciudad Juárez are a national shame). Vargas also wrote “La crónica de un cambio” (The Chronicle of a Change), charging Mexican President Vicente Fox to effect real reform during his term of office (2000–2006), and “La banda del carro rojo” (The Red Car Gang), about crossborder drug smuggling (a 1978 film of the same title recounts this story).

Los Tigres del Norte is one of the leading popular groups performing corridos today. However, they have been criticized at times for their performances of narcocorridos (corridos that may glorify drug culture) such as “Contrabando y traición” (Contraband and Betrayal), one of their most famous songs. The group also recorded Enrique Franco’s “El corrido,” whose lyrics sum up the essence of the form: “Como la corriente de un río crecido / que baja en torrente impetuoso y bravío / voz de nuestra gente un grito reprimido / un canto valiente eso es el corrido” (Like the current of a gushing river / That flows turbulently, impetuously, and bravely / Voice of our people, repressed cry / A courageous song, that is the corrido).

Mariachi music, the form of Mexican music best known abroad, first developed in the state of Jalisco in west-central Mexico in the mid-nineteenth century. Early mariachis were string band ensembles known only to local residents that played at parties, weddings, serenades, and related events. At first their repertoire included local styles from the state of Jalisco, as well as European-derived repertoire; later, as the ensembles gained popularity throughout the country, they incorporated musical forms from other regions of Mexico (and Europe), becoming more representative of the country as a whole. Mariachis first gained national recognition in the early twentieth century when they toured to Mexico City and to the United States. Cinematic portrayals were central to their mass acceptance, and many films from the 1930s onward featured their music. Mariachi music served at that time as a marker of rural, working-class culture. After the Mexican Revolution, mariachi music helped to unify a country torn apart by revolutionary war and class divisions, symbolically bridging the gap between rural and urban areas. Its commercial form since the 1940s and 1950s has adopted complex instrumental arrangements and an Italianate bel canto (quasi-operatic) vocal style, especially for vocal soloists, adding an element of urban sophistication to earlier performance practices. The post-revolutionary government adopted mariachi music as representative of populist mexicanidad (Mexican national pride).

Early mariachi instrumentation consisted of one or two violins, guitar, regional guitar variants such as the five-string vihuela, and harp. By about 1900, the guitarrón (a large guitar-like instrument tuned a fifth lower than the standard guitar) was added, frequently replacing the harp as the ensemble’s bass instrument. Standard mariachi ensembles today consist of about seven to fifteen musicians, with two trumpets (common since about the 1940s), three to six violins, guitars, vihuela, and guitarrón. The first mariachi to make recordings (in 1908) was the Cuarteto Coculense (Cocula Quartet), named after the town of Cocula, Jalisco, which claims to be the birthplace of mariachi. Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán, in existence for more than a century, is the most famous mariachi in the world. It is named after its founder Gaspar Vargas and the city of Tecalitlán in the state of Jalisco, which also claims to be the birthplace of mariachi.

Each instrument in the mariachi has its own role. Violins and trumpets play melodies and are featured in sections and in the form of musical dialogues against one other. The guitar and vihuela provide chordal accompaniment, often by means of flashy, complex strumming patterns. The guitarrón plays the bass line, plucking its notes in octaves to create a louder sound. When harp or other instruments are used, they provide special instrumental color. Musical interest in mariachi music is created mostly through rhythmic shifts, and by contrasting various instruments, as chord progressions tend to be relatively simple.

The term compás is used in much of Latin America to describe the rhythmic structure of a piece of music, but has specific meanings in conjunction with mariachi repertoire. Most commonly, it references recurrent rhythms that serve as the structural basis of certain genres, especially son variants. Most Mexican sones are performed in a fast triple meter and are intended for dancing, zapateado-style. The basic compás or rhythmic cell associated with them consists of two halves, each with six beats. The first half of the rhythm emphasizes particular groupings of notes, for instance beats 1, 3, and 5, while the second half emphasizes different beats such as 1 and 4 or 2 and 5. Guitars and other strummed instruments foreground these rhythms in the ensemble, and the guitarrón usually plays two-measure bass patterns that correspond to them as well. The constant alternation in successive measures between contrasting accents lends a highly syncopated feel to Mexican sones as played by mariachis. Such rhythmic play in triple-meter compositions is common to other kinds of Latin American music as well and may represent the influence of West African traditions on the region’s development. One common word in Spanish for such syncopation, alternating groupings of two and three notes in triple-meter compositions, is sesquiáltera.

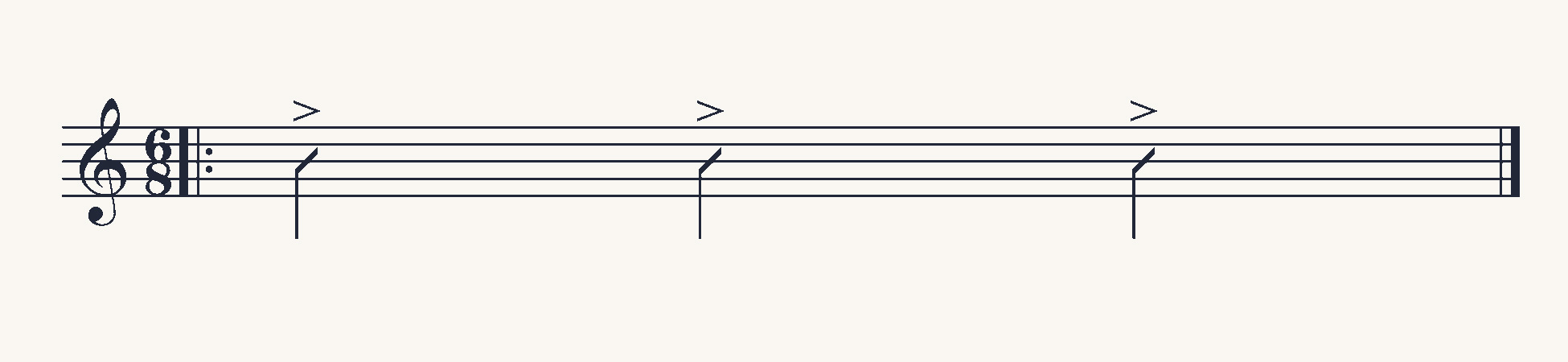

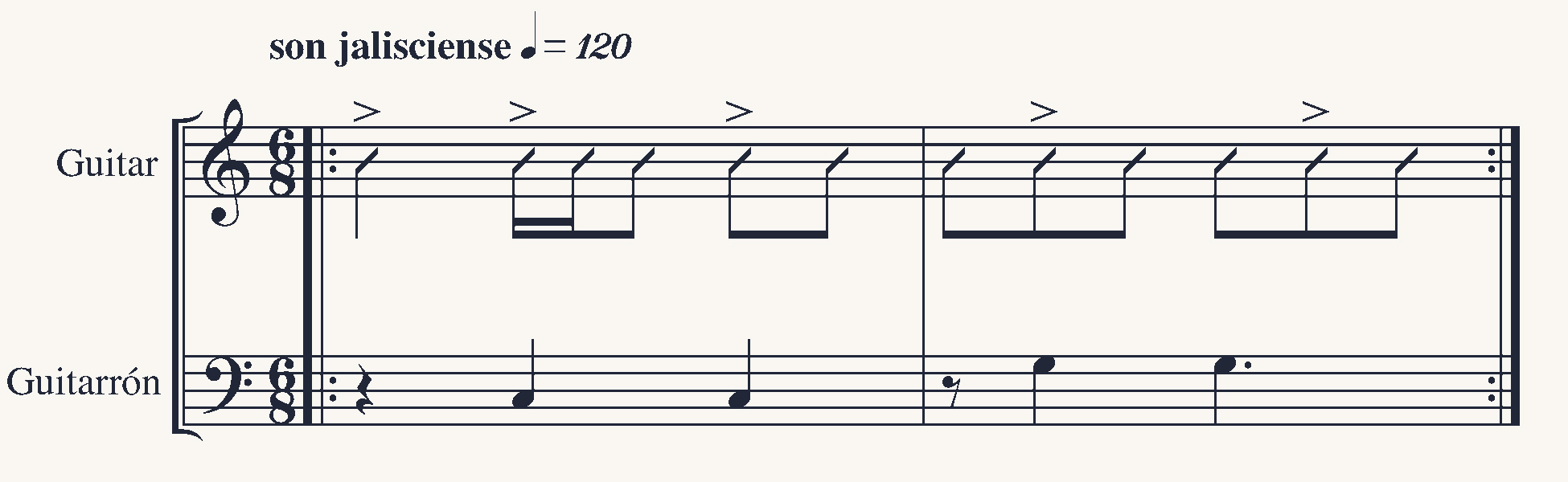

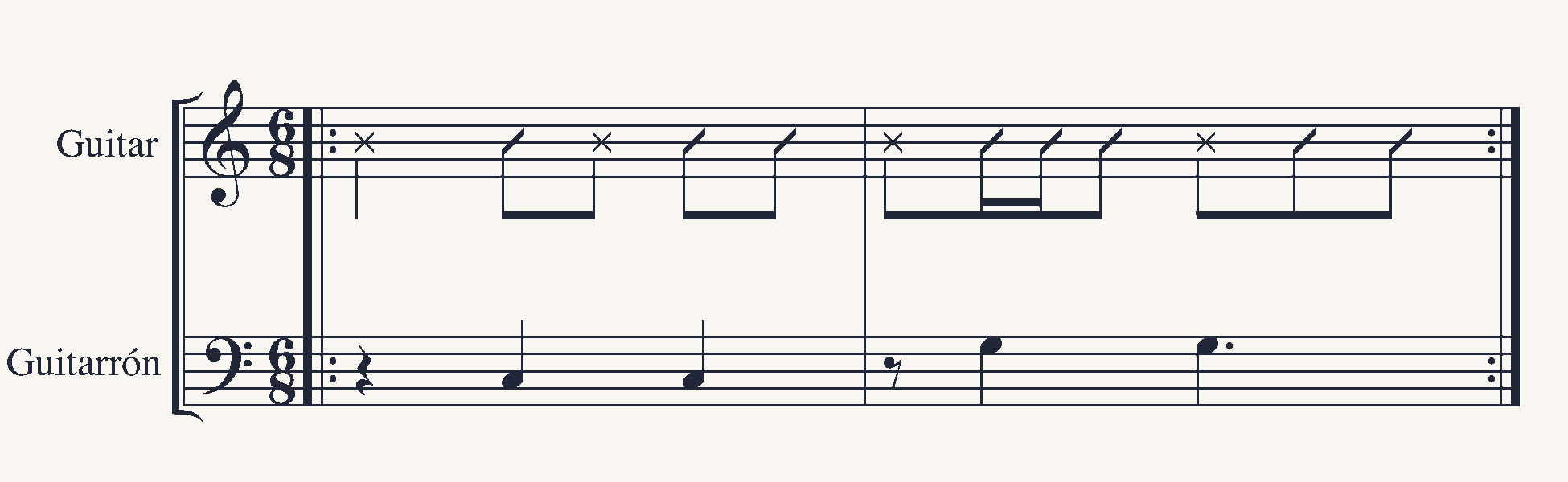

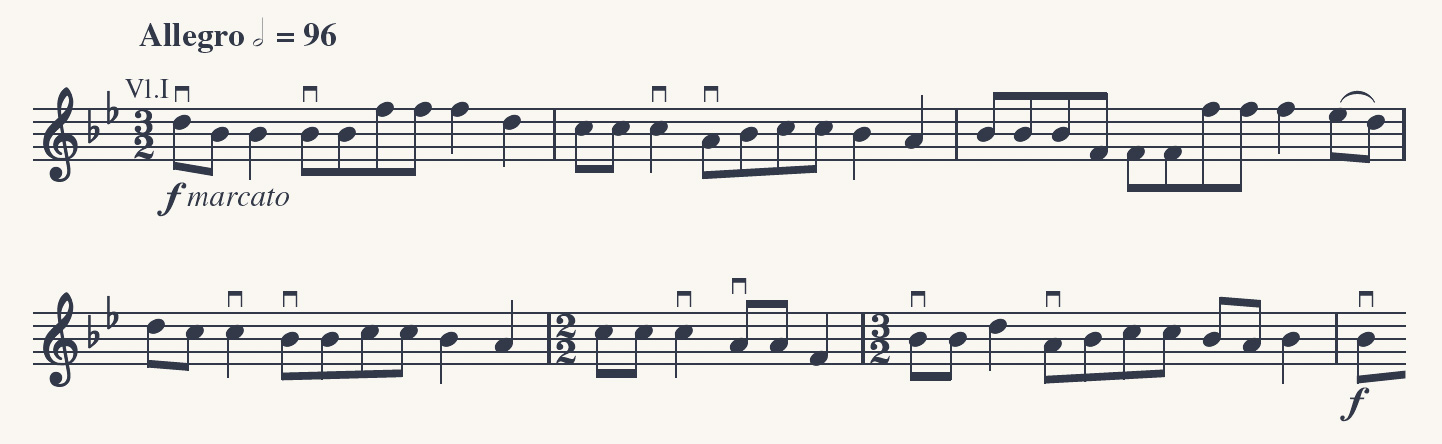

The son jalisciense (the son tradition and repertory from the state of Jalisco), a prominent genre of mariachi music, serves as a means of further exploring the notion of compás. The basic compás associated with this genre consists of a measure of strumming that emphasizes beats 1, 3, and 5 of the <6/8> measure followed by another that emphasizes beats 2 and 5. The first measure, especially, can be interpreted various ways. The guitars and vihuela may strum only on beats 1, 3, and 5, as indicated in Example 3.1.

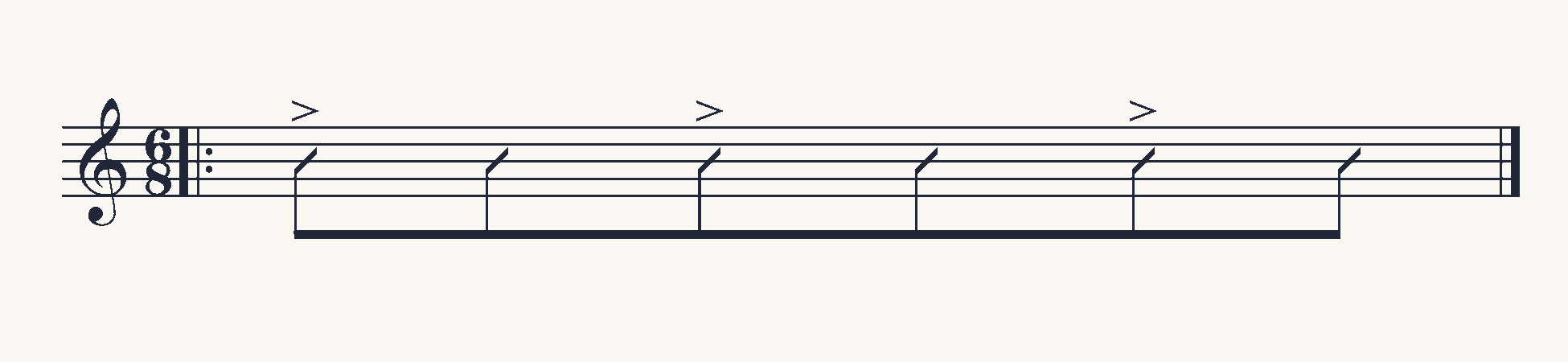

Alternately, they may strum on all six beats but accent beats 1, 3, and 5 more strongly (Example 3.2). Most commonly, however, they play only on beats 1, 3, and 5, but “dress up” beat 3 with a flourish (a fast series of three strums) known as a redoble. Following this, the second half of the measure involves constant strumming in a “down-down-up down-down-up” pattern over the six beats, with emphasis on strokes two and five. Finally, the guitarrón plays a complementary pattern, with the first half marking beats 3 and 5 of the measure and the second half beats 2 and 4. Note that the guitarrón patterns tend to avoid beat 1, increasing the syncopated feel of the music. The complete compás schema of the son jalisciense is provided below (Example 3.3). For simplicity’s sake, all transcribed examples have been written with the less syncopated measure first, but in practice compositions might begin on either side of the pattern.

Mariachi repertory is large and consists of many older traditional sones jaliscienses such as “El carretero” (The Cart Driver), “La mariquita” (The Ladybug), and “El gavilancillo” (The Little Sparrow Hawk), as well as newer pieces. “El son de la negra” (The Tune of the Dark Woman) (Listening Guide 3.4), is one of the most famous of all traditional pieces in this style, and is often performed by Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán (see Figure 3.6). Their recording provides an excellent opportunity for hearing the rhythms of the son jalisciense in context.

It is instructive to compare the rhythms of the son jalisciense with another prominent type of son in the mariachi repertoire, the son huasteco or huapango, and to consider their similarities and differences. The son huasteco is another musical form in a syncopated triple meter, traditionally intended for dancing, and is typically played by a trio of musicians performing on violin, jarana huasteca (a small guitar type), and guitarra huapanguera (another guitar type). The term huasteco refers to the Huastec region in northeastern Mexico, inland from the city of Tampico, including interior towns like San Luis Potosí. The name derives from the Huastec people, a Nahuatl-speaking Indigenous group in the area. Huapango, an alternate name for the same music, is the Nahuatl word for the raised wooden platform on which dancers frequently perform (also known as the tarima). As in the case of the son jalisciense, the son huasteco has made a transition from regional to national popularity, primarily through its adoption by mariachis in stylized form. Today, sones huastecos as played by mariachis may be written in a fast, dancelike tempo, or at a slower tempo primarily for listening.

The compás associated with the mariachi version of the son huasteco is similar to that of the son jalisciense in that it consists of a two-measure repeated pattern, each half with a distinct rhythm. As before, one side of the pattern is straighter or less syncopated, the other more so. The primary element making the son huasteco sound unique is the use of topes (literally, “bumps”), percussive slaps the performer executes with the palm of his/her hand against the deadened strings of the guitar at particular moments while fanning out the fingers. Also characteristic of the son huasteco are frequent falsetto breaks in the vocal melody, a shift from chest voice when singing high notes.

In the transcription below, note that the bass pattern (here played by the guitarrón in the mariachi version of the son huasteco) is the same as in Example 3.4, and that only the guitar style sets this genre apart. An “x” in the transcription indicates a tope or slap. As you can see, they occur every fourth beat, marking off groupings of three beats. Other notes (shaded in the TUBS transcription)indicate the normal strumming pattern. Search for recorded examples of well-known son huasteco pieces such as “La malagueña” (Woman from Málaga), “Serenata huasteca” (Huastecan Serenade), and “El crucifijo de piedra” (The Crucifix of Stone) on your own, and listen for the rhythmic patterns described below.

Mariachis frequently play salon dances such as waltzes, polkas, and even a few well-known nineteenth-century opera and Spanish zarzuela (operetta) overtures. The bolero and Colombian-derived cumbia are an important part of the repertory as well. However, música ranchera is the dominant genre associated with mariachis. It emphasizes full-throated, emotional singing on a wide range of themes strongly felt by ordinary people such as pride of country and region, the many facets of love, marital infidelity, nostalgic memories, and loss through death or abandonment. North American country music is thematically similar in many ways in the content of its song lyrics. The most common form of música ranchera, also known simply as ranchera, is a slow song in either duple or triple meter, usually featuring a solo singer. It appears to have developed as a working-class variant of an earlier urban song form known as the canción. In the same way that the corrido appears to have reworked the romance to reflect the perspective of the poor, música ranchera represents a transformation of middle-class song styles to reflect working-class tastes.

José Alfredo Jiménez (1926–1973) is the best-known composer of rancheras, including “El rey” (The King), “El hijo del pueblo” (The Son of the People), and “Cuando lloran los hombres” (When Men Cry), usually backed by mariachi groups. José Alfredo’s songs, which are often quite romantic in sentiment, seem to speak to the Mexican psyche. One reason why they are so beloved is that they reflect the experiences of the ordinary person. Jiménez was a somewhat controversial figure to the Mexican musical establishment of the mid-twentieth century. Not only did he not read music, but he could not play an instrument, and frequently wrote about topics such as heavy drinking. And yet he demonstrated amazing musical talent, composing hundreds of very popular songs by setting his poetry to melodies and singing them to his musician friends. They in turn would write the melodies down and arrange them for mariachi or other ensembles

The lyrics to “El hijo del pueblo” provide a good introduction to Jiménez’s work. In them, the singer expresses his pride in being a poor Mexican and an Indigenous person (“a descendent of Cuauhtémoc”) and the pleasure he receives in love, drinking, and singing. Since he has nothing, he has nothing to lose, unlike members of high society. (The “Cuauhtémoc” in the lyric refers to the last Aztec ruler of Tenochtitlán prior to its capture by the Spanish in the early 1500s.)

“El hijo del pueblo” (The Son of the People)

Stanzas 1, 5, 6, and 8 only

1. Es mi orgullo haber nacido,

en el barrio más humilde,

alejado del bullicio

de la falsa sociedad.

5. Descendiente de Cuauhtémoc,

mexicano por fortuna,

desdichado en los amores,

soy borracho y trovador.

6. Pero cuantos millonarios

quisieran vivir mi vida,

pa’ cantarle a la pobreza

sin sentir ningún temor.

8. Yo compongo mis canciones,

pa’ que el pueblo me las cante,

y el día que el pueblo me falle,

ese día voy a llorar.

I am proud to have been born

In the humblest neighborhood

Far from the bustle

Of pretentious high society

I am a descendent of Cuauhtémoc,

A Mexican by fortune,

Unhappy in love,

I am a drunkard and a troubador.

But how many rich men

Would want to live my life,

To sing to poverty

Without fear.

I write my songs

So that the people will sing them to me,

And the day that the people fail me,

On that day I will cry.

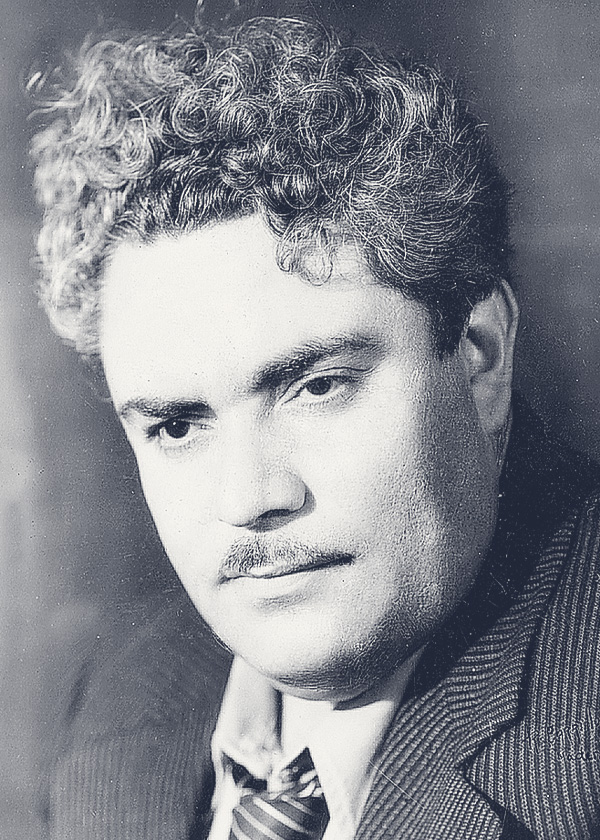

Jorge Negrete (1911–1953) was arguably the greatest charro (horseman) singer to perform in the música ranchera style in musical films, on recordings, and in live concerts, usually accompanied by mariachis. Negrete originally trained as an opera singer, but later turned to Mexican popular music in which he made a strong impact throughout Latin Americas and in the United States. Early in his career, he appeared on Mexico City radio stations and sang in New York nightclubs; and he briefly appeared in Hollywood (billed as George Negrete). By the later 1930s, Negrete had become a national motion picture idol, playing characters that varied from rural charros to urban sophisticates. “¡Ay! Jalisco no te rajes” (Jalisco, Don’t Back Down!) (Listening Guide 3.5), written as a polka and accompanied by a mariachi, is the title song from a famous film of the same name from 1941. It expresses pride in the state of Jalisco and compares its beautiful capital city of Guadalajara to a beautiful woman. The song is an example of música ranchera in the broader sense: a composition in any rhythm or style that lyrically references the countryside and/or local imagery and is performed to mariachi accompaniment.

Many recordings by the major mariachis are readily available, including those by Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán, Mariachi Los Camperos, Mariachi Cobre, Mariachi Sol de México, Mariachi Divas, and other leading groups.

Mariachis today play in a very wide range of contexts, from informal al talón (wandering, on-foot) performances at restaurants to formal events such as fiestas, parades, baptisms, political rallies, marriages, quinceañeras (celebrations for a girl’s fifteenth birthday), and serenatas (serenades). They also give formal concerts, including performances with symphony orchestras. International mariachi festivals are held in places such as Guadalajara and Tucson, Arizona, and mariachi musicians now come from outside Mexico and the United States—Japan and Serbia, for instance. In the past, almost all mariachi musicians were male, but now professional women mariachis perform as well, such as in the Mariachi Reyna de Los Ángeles and Mariachi Divas, both from Southern California. This tradition has changed significantly over time, from an informal, traditional regional practice to a highly polished and stylized commercial form. Mexico’s famous mariachis have often backed superstar vocalists such as Juan Gabriel, Vicente Fernández, and Ana Gabriel in live performances, films, recordings, and on radio.

Leading Mexican songwriters brought the bolero song form to a high point of popularity beginning in the late 1920s. Agustín Lara (1897–1970), a pianist, singer, and film actor, is the most famous. He wrote hundreds of songs, and is especially known for his evocative boleros, reflecting a sense of urban modernity. The Latin American bolero first developed in Cuba (see Chapter 5), but took on new musical characteristics and eventually reached wider international audiences after being adopted by Mexican composers and performers. Lara is a pivotal figure in the “Mexicanization” of the genre and its incorporation into film. He usually wrote for the piano and voice(s), rather than for the guitar, and he composed pieces that reconciled the bolero sound with international popular music of the period, especially mainstream jazz and crooner repertoire from the United States.

Lara’s boleros are often in duple or quadruple meter and usually consist of two contrasting musical sections, which can be repeated. Some works from the 1930s typically incorporate the cinquillo rhythm found in older Cuban boleros. His lyrics present a bittersweet view of unfulfilled, lost, or idealized love, often from a male perspective. However, many women have sung his boleros, most notably Toña la Negra (María Antonia del Carmen Peregrino Álvarez, 1912–1982). Lara’s works contribute to what some writers have called the “cult of the idealized woman.” He tended to portray them either as saintly (as in his song “Santa”) or as sinners (the song “Pecadora”), rarely in a more realistic or nuanced fashion. Lara sang many of his own songs, usually accompanying himself on the piano, in a flexible way that allowed the meaning of the poetry to be emphasized without always following a strict pulse. In Lara’s own performances of his beloved boleros, he intertwined his sinous, sensuous piano solos with his own highly characteristic singing style..

Performers who have recorded Lara’s famous bolero “Solamente una vez” (Only Once; Listening Guide 3.6) include Nat King Cole, Luis Miguel, Julio Iglesias, and Bing Crosby. The Trio Los Panchos recorded one of the best-known renditions. This ensemble, which formed in New York in 1944, consisted of two Mexicans and one Puerto Rican. They recorded the accompaniment of “Solamente una vez” discussed below on two guitars and requinto (here a small guitar type tuned a fourth higher than the regular instrument). Two harmonizing voices support the lead vocal part to create a smooth blend, one that proved highly influential on future generations of Latin American singers. The trío is not only a trio (a group of three musicians), but also a very particular and Mexican type of vocal ensemble. Although the bolero is a song genre from the past, along with the ranchera it is still a well-appreciated form and the romantic music of Mexico par excellence.

Lara’s contemporary, María Grever (María Joaquina de la Portilla Torres, 1894–1951), was the first Mexican woman to achieve significant fame as a composer and as a lyricist. Though she lived in the United States for many years, Grever composed more than 450 Spanish-language pieces, including many boleros. Like Lara, she wrote in several popular forms besides the bolero, including the tango, waltz, and canción. Many of Latin America’s most leading singers performed her music, including the Mexican tenors Alfonso Ortiz Tirado and José Mojica and Alfonso Ortiz Tirado. Among her most famous songs are “Júrame” (Swear to Me) and “Cuando vuelva a tu lado” (When I Return to Your Side). The latter was also sung in English as “What a Difference a Day Makes” by Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby. Her songs are sophisticated, urbane evocations of both melancholy and passionate love.

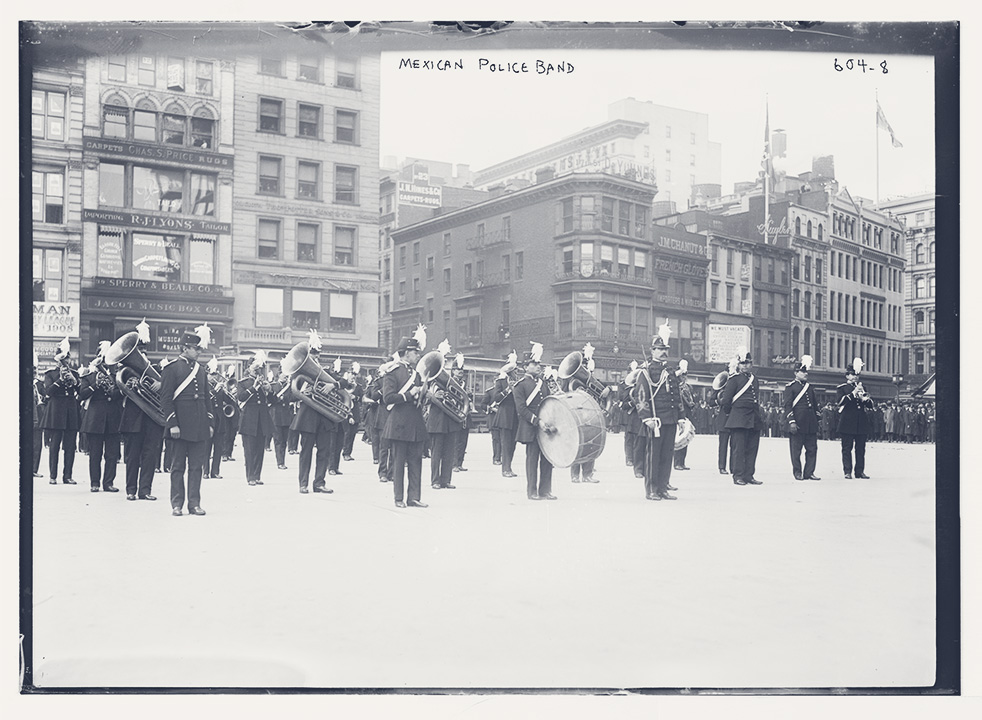

Wind instruments have long been important in Mexican music. From at least the mid-nineteenth century, such ensembles boasted complete families of wind instruments, including woodwinds (flutes, clarinets, oboes, bassoons, saxophones), brass (trumpets, trombones, tubas), and percussion (snare and bass drum, cymbals, timpani). The growth in the number of military and municipal bands brought such music to many areas of Mexico, even small villages, often providing the majority of secular musical entertainment in those places. Wind band repertory reflected both European and Mexican musical tastes, including popular dance music and arrangements of operatic excerpts. The Banda de Policia (Police Band) of Mexico City, led for more than forty years by composer and conductor Velino M. Preza (1866–1945), was one of the most notable ensembles, and made more than 200 recordings in the early twentieth century, including such popular works by Preza as Lindas mexicanas (Beautiful Mexican Women), which is still played by wind bands today. Some Mexican wind band compositions, such as Genaro Codina’s well-known Marcha de Zacatecas (Zacatecas March), dedicated to the city and state of the same name, maintain worldwide fame today.

Today other types of wind bands, often regional in nature, now attract the kind of attention that earlier military wind bands enjoyed. For example, The more than five hundred wind bands from the southern state of Oaxaca are central to everyday life in the region, particularly the Banda de Música del Estado de Oaxaca, the official wind band of the state of Oaxaca. . Wind bands such as this are featured at the annual Guelaguetza festival (wiki), held on two Mondays in July in Oaxaca City. The term Guelaguetza derives from a Zapotec word for offering; the ceremony was originally held to propitiate the gods in return for sufficient rain and a good harvest. Many Indian villages and towns in the state of Chiapas also sponsor wind bands, which serve an important ceremonial role in civic and religious fiestas.

Three wind band styles from the northernwestern states of Sinaloa, Zacatecas, and Durango are especially prominent today in Mexico’s popular music world: tamborazo (Zacatecas), pasito duranguense (Durango and also in Chicago), and banda sinaloense (Sinaloa). They all derive from the earlier Mexican military wind band tradition, and they also share a common repertory, feature similar instruments, and emphasize music for dancing. Though these bands are connected with urban areas, the themes of the songs they play and their costumes (cowboy hats, outfits, and boots) represent a rural, working-class sensibility. Percussion instruments such as snare and bass drums feature prominently in this music against the brass. The tuba (in the form of the over-the-shoulder sousaphone) plays a prominent bassline, with a strong emphasis on the downbeat in either duple- or triple-meter pieces; the tuba also executes rapid solo passages. Some groups incorporate an electric keyboard or synthesizer. Others stress a strong division between the parts: melody instruments (clarinets, trumpets, and saxophones), harmonic accompaniment playing on the “off-beat” (trombone and alto horn), bassline (tuba or other bass instruments), and percussion. All of these northern Mexican regional popular bands favor a strong, brassy sound.

Many regional variants of the wind band format can be heard today. Tamborazo from Zacatecas is named after the bass drum used in the ensemble. Banda Jerez de Zacatecas is one of the best-known groups. It features three singers and uses the following instrumentation: three clarinets, three trumpets, three trombones (with valves instead of the usual slide), tambora (bass drum), tarola (snare drum), cymbals, tuba, and two armonías (E-flat alto horns). The relatively new wind band genre called pasito duranguense originated in Chicago, where many Mexicans from the state of Durango have migrated. Groups playing this style are often smaller than those from Zacatecas or Sinaloa. Grupo Montez de Durango, from Chicago, is one of the leading ensembles; it often performs songs whose lyrics speak of the immigrant experience in the United States. Banda, or banda sinaloense, from the northern state of Sinaloa, is also called tambora after the large drum featured in the ensemble. It has attracted national and international attention. The Banda “El Recodo” de Cruz Lizárraga, from the town of El Recodo, Sinaloa (near Matzatlán), founded and originally led by Cruz Lizárraga, is the most famous group. As with other popular wind ensembles, their repertory and performance styles have changed significantly over the years since Lizárraga founded the group in the early 1950s. Tambora instrumentation today is similar to that of the tamborazo bands from Zacatecas, and they usually have about 15 members. Technobanda, a modern amplified and electrified version of banda sinaloense, is performed at an accelerated tempo by an ensemble consisting of electric bass (used in place of the tuba), electric guitar, keyboard, percussion, saxophone, trumpet, and vocalists.

Although people in the northwestern states of Mexico listen avidly to wind band repertoire of various kinds, northeastern border states favor accordion-based repertoire known as música norteña or norteño (similar to conjunto repertoire in Texas). The typical música norteña ensemble includes a three-row diatonic button accordion, a stripped-down drum set consisting primarily of high hat and floor tom, a large guitar-like instrument with doubled courses of strings known as a bajo sexto, and either an acoustic or electric bass. Sometimes saxophone or other wind instruments are used in these groups, along with electric keyboard. Prominent norteño musicians include the previously mentioned Los Tigres del Norte; singer, songwriter, and accordionist Ramón Ayala; and the group Los Invasores de Nuevo León.

Música norteña developed as a discrete musical style at the turn of the twentieth century on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border. It resulted from multiple influences including the broad dissemination of the button accordion internationally and the presence of many German and Czech settlers along the border, especially in the state of Texas. Accordionists in this style perform flashy right-hand melodic lines, downplaying the bass keys and harmonic possibilities of the instrument, as the bajo sexto and bass fill that role. In polka-influenced music, the mainstay of the repertoire, the bass plays on strong beats while the bajo sexto alternates strumming on backbeats with the execution of melodic runs and fills. Other genres performed by música norteña groups include Mexican versions of the cumbia (see Example 10.2; see also “Mi gente,” Listening Guide 10.6), as well as boleros, rancheras, waltzes, and other forms. In recent decades, a more commercial-sounding version of música norteña has developed in the United States, in Texas, known as música tejana, which is characterized by prominent use of synthesizers and drum machine rather than acoustic instruments. Search on your own for videos and recorded music of the música norteña artists mentioned above, and compare them with tejano performers such as Little Joe y la Familia, Jay Pérez, La Mafia, and Selena Quintanilla.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Mexican youth began to listen to British and American rock & roll and rock music, which they associated with sophisticated, international fashions. The Mexican media initially viewed rock & roll positively and promoted the youth trend. Local talent developed as a response, with emphasis on the refrito or cover tune; groups such as Los Locos del Ritmo and Los Blue Jeans initially performed Spanish-language versions of standard North American hits. The emergence of rocanrol coincided with the rise of the Mexican urban middle class enabled by post-war political and economic stability and growth.

In the 1960s, Mexican rock increasingly adopted an attitude of defiance, reflecting trends in American and British rock, and attracted governmental scrutiny and censorship. The audience for rock also expanded significantly to include the urban poor, not just the middle class, which contributed to the music’s increasingly oppositional tone. The arrival of U.S. jipis (hippies) and drug culture created controversy as well. Even though the genre had been imported from abroad, rock came to be viewed as the “authentic” voice of Mexican youth within a surprisingly short period of time. Students adopted it as they staged protests calling for government reform. In response, government spokesmen began characterizing rock music as dangerous to Mexican society and an affront to traditional values and culture, and on several notorious occasions government forces clashed violently with protesters, including the infamous massacre at Tlatelolco in 1968, during which hundreds of protestors were murdered by Mexican armed forces.

From the late 1960s, influential rock groups such as La Revolución de Emiliano Zapata, Peace and Love, Reforma Agraria, and Three Souls in My Mind (now called El Tri) spearheaded a movement called La Onda (The Wave), which advocated against governmental repression of popular youth culture such as rock music. Some of these names refer to major figures and initiatives of the Mexican Revolution of the 1910s (Zapata, agrarian reform) and suggest the revolutionary cultural experiments being undertaken by youth of the 1970s and 1980s. Continuing to perform today, in its current lineup El Tri puts a particularly Mexican stamp on its music. El Tri’s 1973 song “Abuso de Autoridad” (Abuse of Authority) still evokes a sense of opposition to authority: “Vivir en Mexico es lo peor / nuestro gobierno está muy mal / y nadie puede desvariar / porque lo llevan a encerrar” (To live in Mexico is the worst / Our government is very bad / And nobody can protest because they’ll be taken to jail). New rock music figures/groups appearing since the 1980s include artist Julieta Venegas and the bands Café Tacuba, Maná, Molotov, Jaguares (previously known as Caifanes), and Maldita Vecindad, among others. They mix a wide range of musical influences in their repertory: standard rock, samples of traditional Mexican music, funk and ska grooves (the latter especially associated with Maná), hip-hop, electronic music, punk, heavy metal, and others.

Café Tacuba, founded in 1989, is one of the leading Mexican rock en español bands today; it is named after the famous restaurant of the same name on Tacuba Street in downtown Mexico City. The group presents an eclectic mix of styles that blends elements of Mexican folk music (incorporating genres from Veracruz, for example), punk and electronic music (the group used a drum machine instead of a live drummer until about 2002), rock, and música norteña. Café Tacuba’s very popular song “Chilanga Banda” (Mexico City Gang) is a partly sung, partly spoken recitation of Mexico City slang—over a funk/hip-hop beat—that plays on the sounds of the Spanish consonant “ch” and the word chilanga (meaning someone or something from Mexico City). It refers to modern life among a sector of the working class: “Ya chole chango chilango / que chafa chamba te chutas / no checa andar de tacuche / y chale con la charola” (Cut it out, Mexico City dude / What an uncool job you have! / You don’t look good in a suit / And what’s with the badge?). Cafe Tacuba’s music has been used in the prominent Mexican films Amores Perros (2000) and Y tu mamá también (2001). Argentine composer Gustavo Santaolalla, who wrote the critically acclaimed musical score to Amores perros, has produced most of Café Tacuba’s albums (see Chapters 9 and 10).

Café Tacuba’s song “Eres” (You Are) (Listening Guide 3.7), comes from their album Cuatro Caminos (Four Roads) CD of 2003, inspired by the name of a Mexico City subway station. “Eres” discusses the passion of all-consuming love, reinforced by the frequent repetition of the word eres. The song is a carefully crafted studio product, typical of urban popular music. Most of the song is written over a four-measure recurrent harmonic pattern in A minor: A min-C-E7-E7, with occasional more extended and jazz-influenced chords. Note the use of both electric and acoustic guitars in the recording, at times used separately, at times layered on one another, as well as the use of synthesizer and the studio-altered vocals toward the end. Only partial lyrics are included below; complete lyrics and translations are available online.

Classical music on the European model was first introduced in colonial-era Mexico soon after European conquest in 1521 and has had a significant presence ever since. After Independence from Spain in 1821, sacred art music continued to be performed in Mexico’s many cathedrals and parish churches, as it had since the arrival of Christianity. Secular instrumental and vocal music particularly flourished after Independence in public theaters, as well as in the salons in private homes of the upper and middle classes. Before independence, the Church had been the principal patron of many formal musical events. Subsequently, private and governmental initiatives played a greater role, and by the mid-twentieth century a large infrastructure for classical music existed in Mexico. Some of the important components of this musical establishment included music conservatories; professional orchestras, chamber music ensembles, and opera companies; and governmental patronage of music, including support for composers, performers, and music scholars. This section investigates several topics among many of the important aspects relating to classical music in Mexico––piano music, music for theater and film, and symphonic music––and features three of Mexico’s most important twentieth-century composers: Manuel M. Ponce, Carlos Chávez, and Silvestre Revueltas.

The piano had a significant impact in Mexico from at least the nineteenth century. Many middle-and upper-class Mexican families owned pianos, which were often played by women. An ability to play the piano was considered a sign of sophistication and of good upbringing, much as in the United States and Europe at the time. Preferred repertory included arrangements of works from the Spanish-language musical theater; operatic paraphrases; Mexican and Cuban danzas, usually two-part, 32-measure solo piano works based on the Caribbean habanera rhythm (see Chapter 2 and Listening Guide 2.10); piano fantasies; as well as other classical pieces. From the nineteenth century onward, Mexican and visiting foreign virtuosos performed works by Franz Liszt (1811–1886), Frédéric Chopin (1810–1849), and other European and Mexican composers in public performance venues throughout the country.

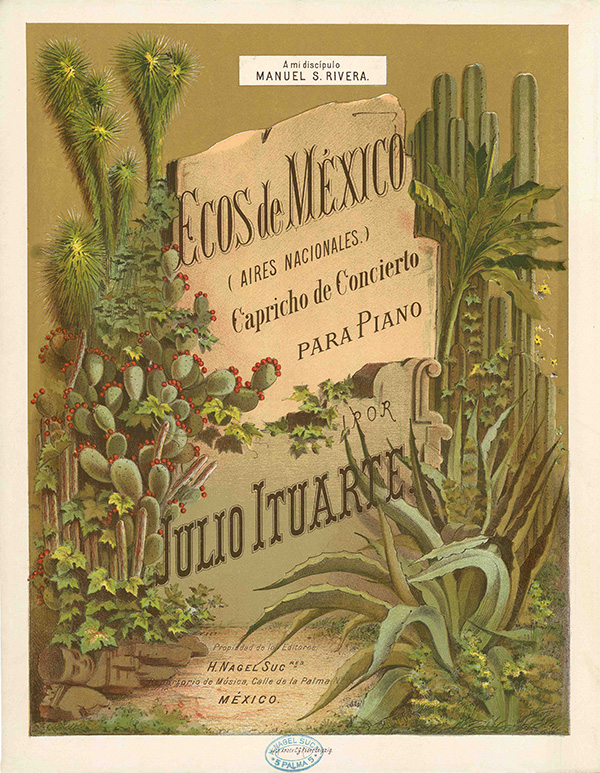

Composer-pianists such as Julio Ituarte (1845–1905), Ernesto Elorduy (1853–1913), and Ricardo Castro (1864–1907) wrote many works for solo piano in the standard European forms. They also composed nationalistic pieces that reflected their interest in Mexico’s rich local musical heritage. In his Ecos de México: Aires nacionales (Echoes of Mexico: National Tunes), Ituarte incorporated numerous well-known traditional son melodies. His work is an elegant musical homage to Mexico that shows the melodic richness of the Mexican folk music on which it is based, as well as Ituarte’s harmonic inventiveness, grasp of balanced musical form, and melodic ingenuity in quoting and reworking the traditional Mexican sones in novel ways. Mexican composers also wrote many piano pieces based on nineteenth-century social dance forms such as the waltz or mazurka. The best-known example is probably the world-famous waltz “Sobre las olas” (Over the Waves) by the Indigenous Mexican composer Juventino Rosas (1868–1894).

In nineteenth-century Mexico, comic and serious operas in Italian became increasingly prominent forms of expression, as did operas by Mexican composers and Spanish theatrical forms such as the zarzuela. Among Mexican composers writing Mexican operas on Italian models at the time was Melesio Morales (1838–1908). Morales studied composition in Europe and wrote four operas in Italian that were performed at the National Theater in Mexico City, the most famous being Ildegonda (1865). Foreshadowing later developments, Aniceto Ortega’s (1825–1875) Guatimotzin (1871) was one of the first Mexican operas to deal with a local subject. It told the story of the defense of Tenochtitlán by the Aztecs against the Spanish.

Mexican composers have continued to write operas. La mulata de Córdoba (1948) by José Pablo Moncayo (1912–1958) retells the Mexican legend of a mulata enchantress who vanished in a puff of smoke when called to appear before the Spanish Inquisition. The most successful Mexican opera composer, however, may well be Daniel Catán (1949-2011), whose Spanish-language operas include Florencia en el Amazonas (Florencia in the Amazon, 1996); La hija de Rapaccini (Rapaccini’s Daughter, 1990), based on Mexican writer Octavio Paz’s play warning of the dangers of blind science; and Salsipuedes, a Tale of Love, War and Anchovies (2004). Catan’s opera Il Postino (The Postman), based on the 1994 film about the life of Chilean poet Pablo Neruda when in exile in Italy, premiered in Los Angeles, California in 2010, starring the world-famous Spanish tenor Plácido Domingo as Neruda. Several of Catán’s operas have become regular repertoire pieces, especially Florencia en el Amazonas.

Recordings of Morales’s Ildegonda, and Catan’s La hija de Rapaccini, Florencia en el Amazonas, and

Il Postino are available.

In contrast to the operatic repertory with its more universal themes, Spanish-language zarzuela of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries performed in Mexico frequently based its stories on Spanish or Mexican topics. It also incorporated spoken dialogue instead of the recitative (declamatory, speech-like singing) used in all-sung opera, and prominently featured dance rhythms and song forms. Popular zarzuelas frequently performed in Mexico included Spaniard Tomás Bretón’s very popular La verbena de la paloma (The Festival of the Dove, 1894), set in working-class Madrid, and Luis G. Jordá’s Mexican work Chin-Chun-Chan (1904). Musical revues, known as revistas, also held the stage in Mexico during the first half of the twentieth century. These were similar in many respects to Broadway musical revues such as the Ziegfeld Follies of the 1910s and 1920s. These Broadway shows had a minimal plot and stressed songs (often with erotic lyrics), dances by scantily clad chorus girls, and comic skits. However, Mexican revistas were often more politically charged and satirical than their Broadway counterparts, which sometimes led to their suppression or censorship by Mexican governmental authorities.

In the twentieth century, music to accompany motion pictures assumed an important role. From about the turn of the twentieth century, through the 1920s, piano, organ, or orchestral music almost always accompanied silent films in Mexico. From the 1930s, Mexican motion picture studios produced films with soundtracks and employed some of Mexico’s leading songwriters and composers. Their films utilized scores featuring full orchestras, as well as mariachis and other Mexican popular ensembles. A notable documentary film that included an important classical score was Redes (The Wave, 1936), with music by Silvestre Revueltas. Indeed, the Mexican motion picture industry enjoyed a golden age between the 1930s and the early 1960s, with many film genres featuring sound tracks with a variety of musical styles: the sentimental tearjerker; the romantic swashbuckler; the comedia ranchera (rural comedy); cabaretera films, dark tales of urban deception and redemption, often dealing with cabaret girls, nightclubs, and prostitutes; and comedies featuring the antics of Cantinflas (Mario Moreno Reyes, 1911–1993) or Tin-Tan (Germán Valdés, 1915–1973). Many film releases continued to center around song and orchestral music through the 1970s. Films from past decades continue to air on television and circulate on DVD and streaming services, and songs from the Mexican cinema retain an important place in the Mexican musical imagination. Among film scores of the past several decades, Argentine composer Gustavo Santaolalla’s music for the critically acclaimed Mexican film Amores Perros (2000) is especially notable.

DVDs of the following classic Mexican motion pictures in various genres, all of which include musical scores, are available: the cabaretera film Aventurera (Adventuress, 1950); the rural dramas María Candelaria (1944) and Flor Silvestre (Wild Flower, 1943), with Dolores del Río and Pedro Armendáriz; and the comedy Dos tipos de cuidado (Two Careful Fellows, 1953), with Jorge Negrete and Pedro Infante. Also look for the many films by Cantinflas and Tin Tan, with their musical scores.

Like their counterparts in the United States, Mexican classical composers embrace international models while also referencing local musical, literary, and historical elements in their works. During the Porfiriato, or rule of President Porfirio Díaz in the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Mexican government gave subsidies to musicians to study in Europe with master teachers. Paris was an attractive location for study for composers such as Ricardo Castro and Manuel M. Ponce. When they returned to Mexico, they opened their own private music schools, and many taught at the National Conservatory in Mexico City.

The Mexican Revolution (1910–1920) disrupted but did not end classical concert and operatic life. In its aftermath, the Mexican government’s interest in encouraging representations of indigeneity and Mexican themes encouraged stylistic innovation in many artistic fields, including classical music composition. Diego Rivera painted his famous murals on Mexican subjects at this time. With her paintings representing Indigenous themes, especially the tehuana (woman from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec), Frida Kahlo, Rivera’s wife, also contributed to this trend. Concert activity increased significantly from the 1920s on. In 1928, composer Carlos Chávez founded the Orquesta Sinfónica de México (Mexican Symphonic Orchestra, now the Orquesta Sinfónica Nacional—the National Symphony Orchestra), which he directed for many years. Under Chávez’s leadership, the ensemble performed numerous works by Mexican composers, North Americans such as Aaron Copland, and Europeans. Chávez also performed his own pieces regularly, as well as those of Ponce, Revueltas, José Rolón, and other Mexican classical composers.

The opening of the Palacio de Bellas Artes (Palace of Fine Arts) in Mexico City in 1934 stimulated the growth of classical music. This important performance space is located in the downtown city center, near the Zócalo (the main plaza), the Cathedral, and the National Palace, and is the venue for orchestral, chamber music, choral, operatic, theater, and dance performances, including the Ballet Folklórico de México, the world-famous professional folkloric dance troupe.