The over 44 million inhabitants (based on a 2015 estimate) of this relatively small isthmus correspond to the highest “nation state density” in Latin America per square mile forming seven contemporary countries: from northwest to southeast, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Panama. Although a relatively small geographical area, a narrow arc under 202,000 square miles and about 1,140 miles end to end, this zone encompasses a variety of ecosystems. The Caribbean littoral from Belize through much of Costa Rica are tropical lowlands, which in Nicaragua extend far inland. A mountainous plateau extends south from the Guatemalan highlands to encompass most of Honduras, the middle portion of Nicaragua, a great deal of Costa Rica (including the most densely populated part of the nation), and ending in northern Panama. Along the Pacific Coast, low lying plains and small coastal hills hold the bulk of the population of El Salvador and Nicaragua. Central America can be roughly divided into Pacific Ocean- and Caribbean Sea-bordering zones. The northeastern Caribbean region consists mostly of low-lying tropical plains and savannahs, crossed by several major rivers in Honduras and Nicaragua. The southwestern Pacific region contains a more mountainous central area, from the large Guatemalan highlands through to southern Costa Rica, together with the coastal plains and hills that hold the bulk of the population in El Salvador and Nicaragua. As its name implies, Central America is a meeting ground between two large continents, and shares flora and fauna from both. It contains the narrowest land division between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, only 30 miles in one part of Panama, which has made it a focus of outside economic and political interest since the conquest.

The Caribbean region was inhabited by peoples related through a shared Chibcha language prior to European contact. The remoteness of much of the territory and a lack of easily exploitable natural or human resources slowed the consolidation of Spanish control; by the seventeenth century the English had greater contact throughout much of the eastern coastal area. The inability of the Spanish to extend their control from coast to coast in Central America has meant that the eastern zone’s primary cultural and economic relationship with the outside has been with the greater Caribbean basin.

In the west, the Spanish quickly subdued local Indigenous peoples. To the north, Mayan city-states had collapsed only a couple of centuries earlier, for reasons still not fully understood. The coastal Chorotega-Mangue peoples of Nicaragua suffered a rapid 90% depopulation owing to murder, disease, and forced deportations to Peru as slaves. Musical performances of native repertoire were prohibited and native documents burned to eliminate cultural resistance to European rule. Similar fates befell the Lenca communities in north-central Honduras, the Pipil in El Salvador, and other peoples. During the colonial period a widespread process of racial and cultural mixture along the Pacific Coast region formed a majority mestizo ethnicity and culture south of Guatemala. In mountainous Guatemala (like the state of Chiapas in neighboring Mexico) the Maya’s relative inaccessibility aided their cultural survival. K’iche, Kaqchikel, Mam, and other Mayan groups still number almost half of Guatemala’s contemporary population of over 18 million; almost all the rest is mestizo (usually called ladino.)

The large area west of the Caribbean did not allow for the cultivation of crops (like sugarcane) that led to the mass importation of Africans elsewhere in Latin America. A relatively small African presence was established in the late 1700s on the Honduran coast by the arrival of the Garífuna, or Garinagu, mixed Carib and Arawak Indian and African slaves deported from St. Vicente island by the British after an unsuccessful rebellion. A small number of slaves and escaped slaves also dot the coast. West Indian immigrant laborers settled in the eastern region from the late 1800s onwards. A lack of contact, and sometimes even a segregation of the two zones, continued well into the 1950s; Afro-Costa Ricans were actually barred by apartheid laws from entering San José, the highland capital. Distinctions between the Pacific and Caribbean areas began to break down significantly when various mestizo political leaders moved to more fully integrate them. The spread of popular music from the Afro-Central American Caribbean zone to the mestizo west has been key in this process, introducing citizens of the same country to one another for the first time, though integration remains far from complete.

Too often the more European descent ruling elite has utilized crude and violent policies to maintain a divide between themselves and Indigenous and poor mestizo populations. In the nations north of Costa Rica a series of tyrannical military regimes, some of the worst in Latin America, has enforced this social order. In 1932, for instance, near-starving Indigenous peasants in El Salvador tried to unseat their military rulers but failed. Soldiers and landowners slaughtered over 30,000 people within days, an event still called La Matanza (The Massacre.) In the aftermath, Indigenous people feared to speak their languages or wear traditional clothes; musicians burned almost all of their small-sized marimbas. Around the same time in Nicaragua, Augusto Sandino organized a peasant militia to combat that nation’s corrupt military, supported by U.S. Marines, until his murder brought in the Somoza dictatorship that lasted for over four decades. Two negative terms used to denigrate Latin America come from this period: “banana republic” was coined to describe the dominance of U.S.-based United Fruit over national politics of Honduras; and “the backyard of the United States” describes the overt and covert intervention of the U.S. government in Central American internal affairs.

Not until the late 1970s did social movements in Guatemala, El Salvador and Nicaragua finally grow enough to take on the oppressive social conditions. The successful growth of community and workplace organizations brought on a brutal repression that spiraled into full-scale war that brought international attention to the region. The effects of this period still reverberate in Central American societies. For example, at great human cost the Somozas were defeated by the leftist Sandinista (from Sandino) Front in 1979, only to face a U.S.-sponsored economic and actual guerilla military war that debilitated the attempted social reforms. The immense weight of United States power also underwrote severe repression in El Salvador and Guatemala, the latter reached levels of genocide against the rural Mayan population.

The peace treaties in the early 1990s basically achieved the U.S. government’s goal of keeping Central America’s ruling strata on top, but North American promises of investment and rebuilding never materialized. Instead, the gradual imposition of neoliberal privatization worsened economic conditions for the popular classes north of Costa Rica and a huge human migration has ensued to the U.S. Tourism, coffee and maquiadores, sweatshops particularly manufacturing clothing, are the largest hard currency generators for Guatemala and Honduras. In El Salvador for many years remittances from abroad have been the biggest “industry.” Organized gangs grew to such strength that El Salvador’s government took the drastic step of mass imprisonment to try and counter their threat. Nicaragua’s turn towards rule by one family (Murillo–Ortega) and economic stagnation mostly due to continued hostility from the U.S. has led to the emigration of over a half million Nicaraguans to Costa Rica. In general, the lack of sustained economic development throughout the northern part of the region continues to impact music performance, from traditional repertoire to local popular music to chamber orchestras

Costa Rica avoided the same level of violence as its northern neighbors with a successful institutionalization of electoral politics and an economic social safety net that ameliorated class conflict. This relative peace allowed Costa Rica to economically develop to achieve the highest per capita living standards on the isthmus. Although in recent years it has struggled to absorb the large-scale Nicaraguan immigration, Costa Rica’s socioeconomic position remains the highest in the region. Panama’s development has been characterized by its unique position between continents with a narrow land mass that offers the possibility of connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. After an earlier French failure, the United States finished the Panama Canal in 1914, eventually ceding ownership back to Panamanians by the end of the century. In recent decades Panama City blossomed into a substantial international financial hub, though the benefits have been limited to a new elite many of whom inhabit the large number of new skyscrapers that dominate one part of the capital city. Tourism, especially newer eco-tourism, has grown in Costa Rica and to a lesser degree in Panama. The illegal drug trade continues to threaten extending its reach using Central America as a stop between South America and the driver of the trade, the U.S. market.

There are nearly 3 million Mayan descendants, almost all in Guatemala and Chiapas, Mexico. Many communities have continued pre-contact religious beliefs and rituals, though they have absorbed some outside influence over centuries. Probably the largest cultural change has been the recent intrusion of Protestant evangelism, sponsored by North Americans. Ancient and contemporary Mayan beliefs do not adhere to a rigid division between religious and secular aspects of life, including music, rather all things, such as nature, have at least some degree of sacred significance. An important musical example is the linkage of the sun deity with the tun (or tun-tun), an onomatopoetically named two-note instrument formed by cutting an “H” into the top of a suspended hollow log and struck with mallets.

The same instrument is called teponaxtli among central Mexican-origin Nahuatl speakers (see the decorative stone example from the Aztec elite in Fig 3 in Chapter 2_.) We have evidence of pre-Contact existence of this instrument in western Nicaragua from a large, tall stone statue that depicts a two-note slit drum, in this case a teponaxtli brought by Nahuatl speakers when they migrated from central Mexico centuries before the arrival of Spanish adventurers.

Other instruments are documented in accounts of contact-generation Spaniards or archeological iconography, such as the amazing mural at Bonampak in Chiapas that neighbors Guatemala. Painted in 790 for royalty, it depicts a large musical ensemble performing for a ritual sacrifice of a captive. These include long trumpet-horns and tortoise shell and several large rattles. We can only guess at the actual music that was played; even contemporary reconstructions of the instruments give only a rudimentary idea of the sounds and how they were combined.

Music continues to play a central role in Mayan life. These include song cycles and dance-dramas that recount origin myths. The Rabinal Achí of the K’iche’-speaking people is the dance-drama best known outside the Mayan community and the most elaborate one to have survived colonial suppression. The name in K’iche’, Xajoj Tun – dance with tun – shows the prominent role of the tun drum. Other music genres include ancestor songs to invoke spirits of the departed; songs of healing; and a corpus of music determined by the Mayan calendar that relates to agricultural cycles. A well-balanced world requires music to be performed as dictated by ancestors and supernatural forces, and encompasses many forms, for instance: solo singing; cane flute repertoire, often paired with small double-headed drums; guitar pieces on modified local instruments; and tun music, sometimes played together with long valveless horns or European-style trumpets (as in the Rabinal Achí.) Following Mayan belief, most Mayan instruments are gendered, i.e., classified as either male or female. Actual musical performance, however, remains limited to men.

The marimba serves as both a signifier of a musical unity as well as a prism into the wide cultural diversity on the isthmus. Marimbas consist of a series of wooden keys in increasing size attached to a frame and struck with mallets. The names marimba and malimba exist in several languages in sub-Saharan Africa where it is widely dispersed in various forms. No one knows exactly when or precisely where, but this instrument first appeared in several places in Latin America when captive Africans began to re-create them. In some places where we know marimbas once existed, like Brazil, the marimba has fallen out of use. But they are still found in African-American communities along the Pacific Coast of Colombia and Ecuador; in 2015 UNESCO recognized their continued vibrancy and importance. The first written mention dates to 1680 in Guatemala City, Guatemala. The Indigenous population adopted them from the few Africans brought into Central America, a group so small that they mixed with the Indigenous and mestizo population and eventually disappeared as a distinct group. Over time the marimba has become associated exclusively with Indigenous peoples, leading to unfounded assumptions about its Mayan ancestry. My own speculation is that the similarity of using a mallet to strike a tun and/or teponatxli made for easy adoption of recreated wooden keyed African marimbas.

Over the last two centuries, social pressures and the desire to perform more urban and European-based music led to experiments by Central Americans and Mexicans to enlarge and change the form of the marimba. Historically there have been three main types, and contemporary Guatemalan marimbas provide a useful example because all three types are still in use there: the marimba de tecomates; the marimba sencilla; and the marimba doble.

Marimbas have various names in Mayan languages. The Spanish name (above) comes from term used for the resonators under each key. This earliest form of marimba has a hoop, or an arc, of wood attached on each end of the frame; a single performer sits inside the hoop. The instrument’s single row of 28 large keys is diatonic (like the white notes on a piano.) Keys are cut from a heavy, dense type of wood; their weight usually obliges the marimbista to prop up the front of the marimba with a stick. This marimba is rarely seen outside of Mayan villages deep in the countryside, sometimes accessible only by foot. It provides music at rituals, such as the blessing of seeds before planting, as well as in secular contexts like recreational dancing. Often it is accompanied by a small drum and vertical cane flute.

This instrument was created to play popular music beginning in the 1800s. “Sencilla” (simple, single) with one row of keys, it is also diatonic. Urban Mayans and mixed-race mestizos expanded its range to four to five octaves (33 to 40 keys), so the arc had to abandoned in favor of legs to support the increased weight. Multiple musicians can play on a marimba sencilla: one carries a bass line, and others produce chords and harmonized melodies. Gradual deforestation of the region led builders to design rectangular wooden boxes to replace the tecomates. In Guatemala, Honduras, parts of El Salvador and Costa Rica, these marimbas play alone or together with a trap drum set and other percussion. The growth in instrument size reflects the parallel growth of small towns and cities and their increased contact with musical influences outside traditional village life.

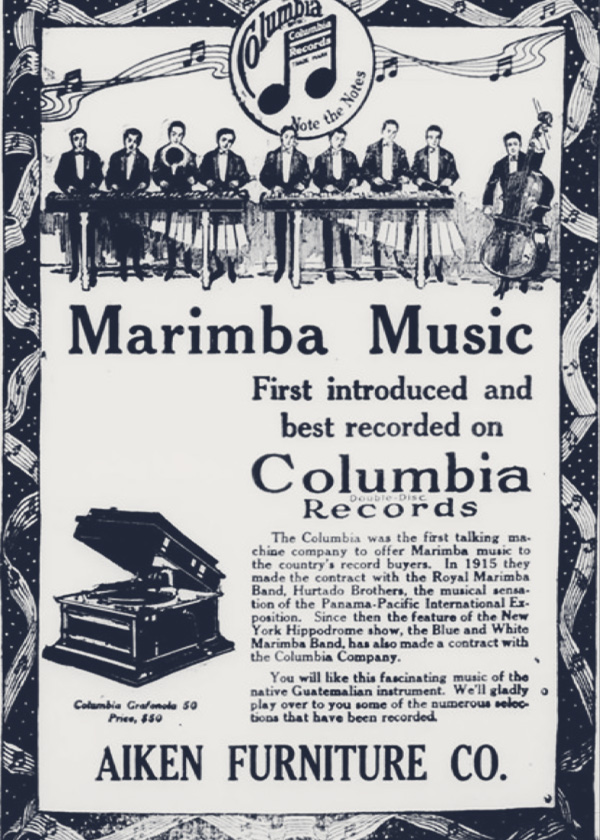

Apparently unbeknownst to one another, Sebastián Hurtado of Quetzaltenango, Guatemala in 1894, and then Corazón Borraz Moreno of Chiapas, Mexico in 1897 added an upper row of keys like the black keys on a piano to the marimba sencilla. This innovation eventually changed the attitude of the well-heeled elite when they heard marimbas reproduce music previously only heard in the parlors of wealthy homes. The marimba doble soon became very popular in urban areas throughout Central America, and as early as Hurtado’s first trip in 1908 marimba doble groups toured the United States and Europe as novelty acts. Slowly, the marimba was adopted and transformed outside Central America with metal cylinder resonator tubes to become the vibraphone instrument currently used in jazz, new age and Euro-classical music.

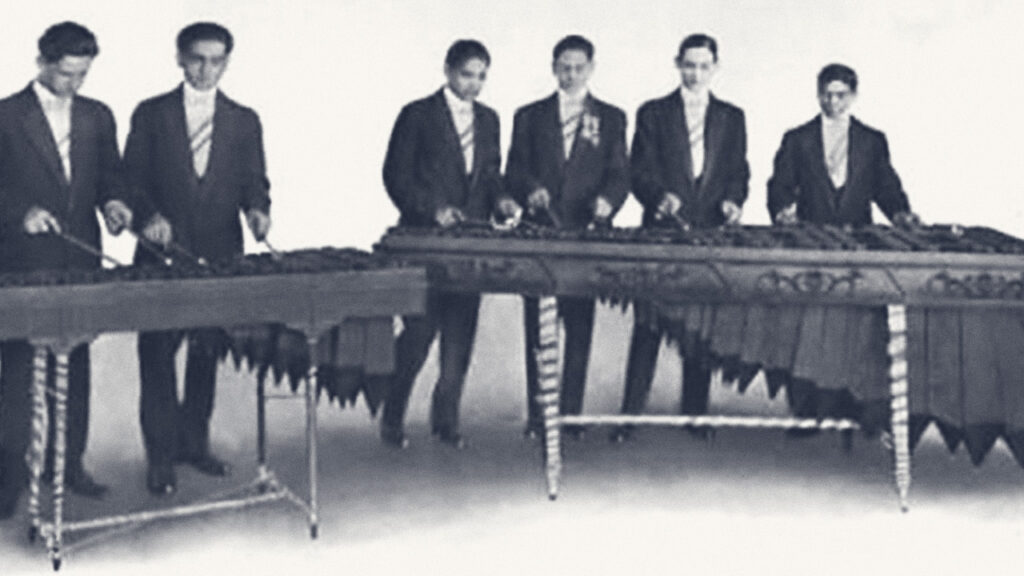

In Central America, musicians often combine a four-person lead marimba with a smaller three-person one to produce a “wooden wall of sound” where the lyrical melodies result from precise repetitions on the same keys by expert musicians. Note that all African and Latin American marimbas have a distinctive “buzzing” sound; when the marimba was transformed outside of Latin America this buzz sound was eliminated. A hole near the bottom of each resonator is surrounded with thick, black bee’s wax, and some kind of membrane stretched across it (see Fig. 4.5.) Traditionally the thick webbing around spiders’ eggs were used, but now dried pig intestine is preferred, following the same principle that makes a kazoo buzz.

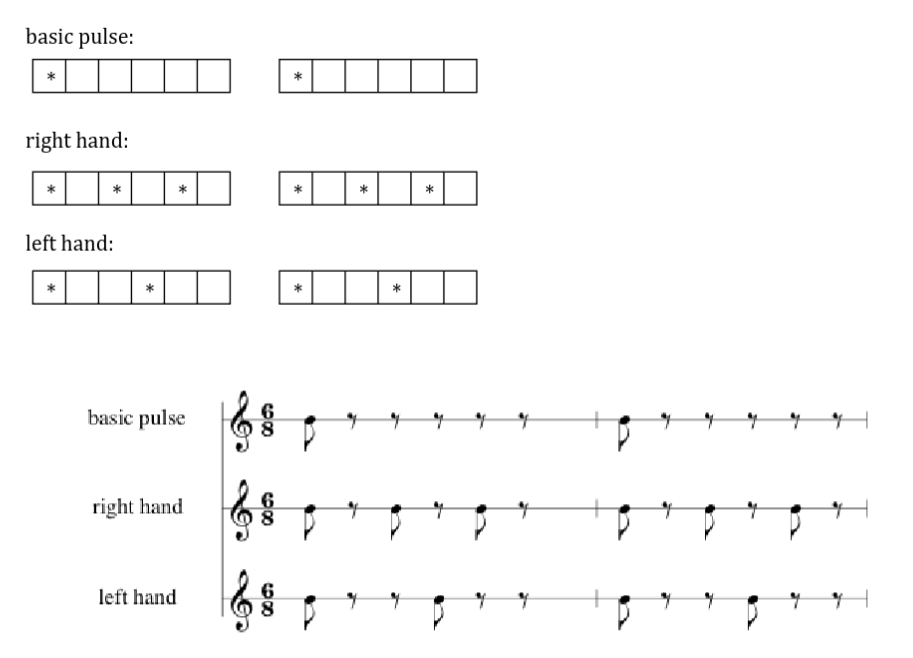

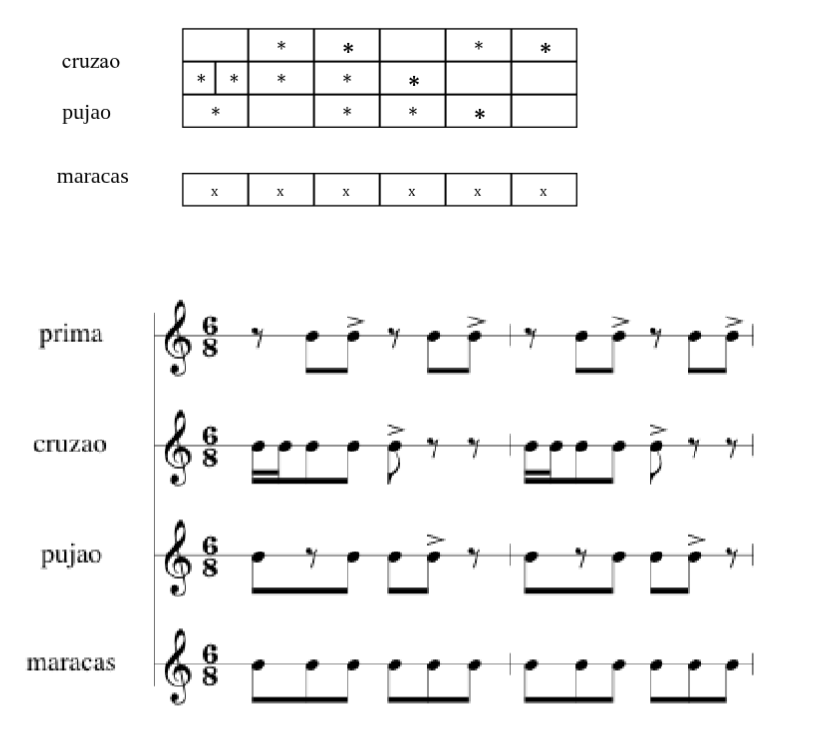

The Nicaraguan marimba de arco offers a clear example of how closely tied dance often is to marimba music. Practically all pieces are in a major key. The tempo is quick, usually in 6/8, though some sections switch to 3/4. The standard format is that of a trio: a guitar strums a triple pattern and sits by the bass keys of the marimba, and a small, high-pitched 4-metal stringed guitarilla sits by the treble keys and strums a quick 6/8 rhythm. The marimbero plays two musical roles: in his left hand, a single mallet (sometimes two) alternates primarily between two notes in a four-beat pattern, and the right hand continually changes the position of two mallets between thirds, sixths, octaves or even a single note to play and harmonize the usually syncopated melody based on a pattern of 6 beats. You can feel this metric duality by following Ex. 1. below. First try the main beats with both hands; then change just the right hand in groups of 3 beats; then back to both hands on the main beats; then try the left hand in groups of 2. Whenever you feel ready for your first step, add them together to beat twos against threes.

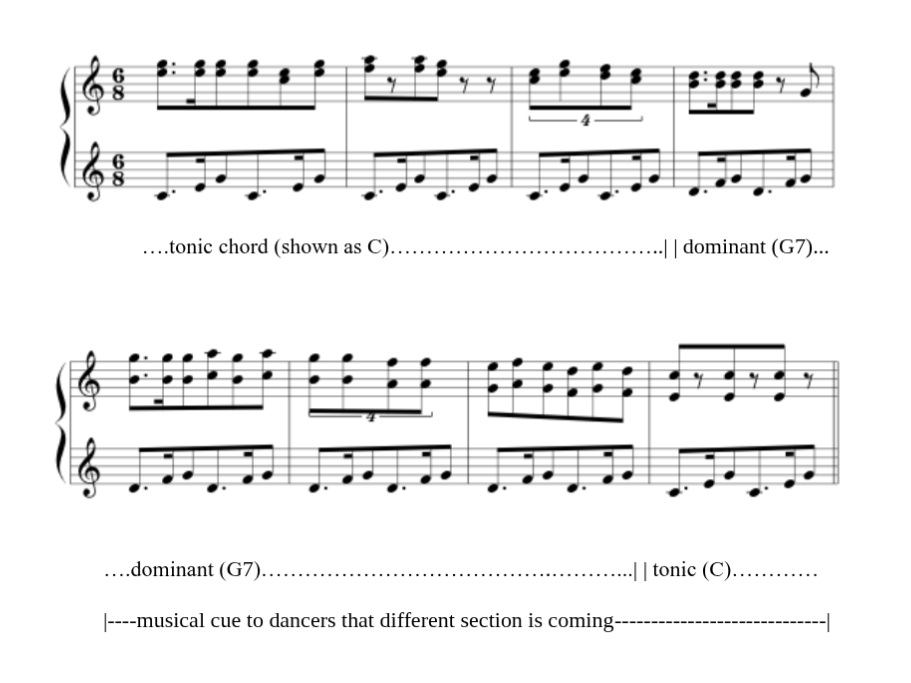

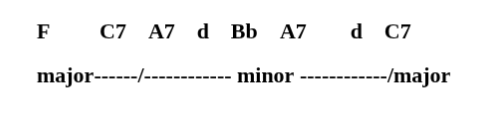

The form of pieces is usually either ABAB, or ABABA, with some exceptions. Dances areperformed by couples, for fun in private homes or more publicly on saint’s day celebrations. During the latter, groups of four to eight couples practice their choreography for weeks. During processions the marimba is carried and couples line up by sex and face each other, trying to move sideways down the street as they dance. Groups go from one sponsor’s house to another and one pair dances at a time in the living room. The marimba trio may be jammed behind a wall of spectators, but the structure of each piece is so standardized that they and don’t require eye contact with the dancers. This didn’t used to be the case: the musical structure used to be quite flexible and marimba players would cue each section. Constraints of recordings and demands of new semi-professional dance troupes codified the repertoire into its current form. The cues still remain in the music: Ex. 4.2 shows the marimba de arco’s playing at the point that cues the next section, and the chords that change at this point (at 0:38 to 0:46, and 1:45 to 1:50 in Listening Ex. 4.1.)

Though women dance, before this century only a few women from marimba families learned to play and then only up until reaching adolescent. The explanation usually given is that female musicians would not be able to perform in the heavily male-dominated world of fiestas and parties. For example, in the 1990s one daughter of a famous Masaya dancer mastered the instrument and appeared on television, yet the nature of alcohol-infused social scenes far from home deterred her from pursuing a professional career as a marimba de arco musician. In the last two decades government funded instruction has enabled several women to learn the basics of the traditional repertoire. Recently the adult daughter of a well known dancer has mastered the instrument enough to play on stage with other marimba players in some folk dance group presentations in Managua, but so far no one has ventured into an actual professional career.

If you could visit mid-20th century Nicaragua, you would find marimba de arco ensembles, mostly in certain regional towns, and marimba doble groups in larger cities. If someone told you that only one instrument survived to the end of the century, wouldn’t the larger chromatic instrument seem the obvious choice? Yet the opposite occurred. The close identification between the marimba de arco and the folk dance it accompanies led to its increasing visibility (and audibility), especially after the 1979 Sandinista revolution. The public’s identification with feelings of nicaragüanidad, “Nicaraguan-ness” granted the 22-key marimba a symbolic power that allowed it to persevere while larger marimbas were marginalized. This provides us a lesson that what is important about music is its social meaning, not the complexity of its formal structure. Nicaraguans have access to the world’s many technological sonic devices, yet the marimba de arco still holds a special place in people’s hearts in contemporary culture.

Compare Listening Example 4.1 with marimba de arco selections on ¡Nicaragua Presente!: Music from Nicaragua Libre, as well as compilations like Music From Honduras, Vol. 1 and Music from Guatemala, Vol. 1. Large Guatemalan and similar Mexican ensembles of marimbas grandes abound and some bands cover seemingly every type of music possible to play on wooden keys

Countless popular musical styles that have developed over the last hundred years in this region. In Guatemala the marimba has retained a place of national prominence where it is heralded as the “national instrument.” Mayan-Guatemalans, now about half the population, still intensely identify with the marimba, and additionally a singular piece of legislation helped cement the instrument’s place among mestizos. In the 1950s the government decreed that all radio stations had to play a significant block of national marimba music every morning. While at first some chafed at this rule, in time the law had its desired effect. Today Guatemalan marimba doble ensembles, often expanded with drums, bass and horn sections, remain popular and interpret all kinds of musical styles.

Central American popular music has had three major waves of exposure outside the isthmus: the above-mentioned tours of marimba groups in the early 20th century; the spread of protest music in the 1970s and 80s; and the popularization of Garífuna (or Garinagu) music since the 1990s. The violent social upheavals of the 1970s produced at least one positive result: a prolific outpouring of new music and its dissemination internationally. Music with social or political content played a key role in mobilizing the population for more social equality and democracy. The 1979 overthrow of the Somoza dictatorship and the extended warfare throughout the 1980s in the northern half of the region ocused the world’s attention on Central America as never before. Exiled music groups from El Salvador and bands in Sandinista-led Nicaragua (1979-1990) toured Latin and North America and Europe; several albums were released on labels outside the region.

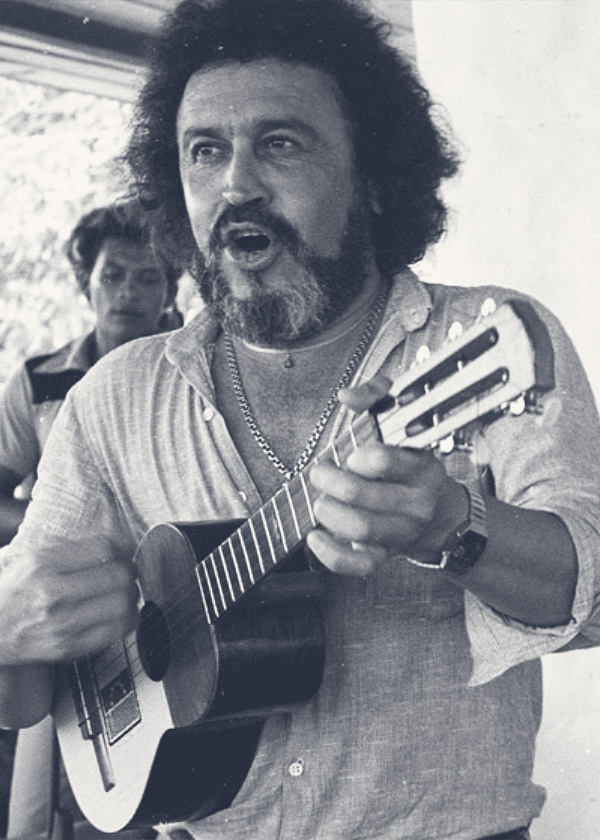

Far and away the best-known musical figure from Nicaragua is Carlos Mejía Godoy. It would be hard to overestimate the fundamental importance of his music to motivate his compatriots to first overthrow the dictatorship, and to work to transform the nation in the 1980s while simultaneously defending it from attacks on civilians by the U.S.-funded “contra” (counter[-revolutionary]) forces based in Honduras. Mejía Godoy’s primary medium was a song style created as recently as the 1930s known as the son nica that borrowed its defining rhythm from the marimba de arco trio’s guitar triple-stroke strumming pattern. Certain patterns of melodies and the major key of son nica songs also stem from marimba repertoire, which is consistently in a major key.

Following two hugely popular albums, Carlos Mejía Godoy composed a mass based on the tenets of Liberation Theology entitled La Misa Campesina Nicaragüense, The Nicaraguan Peasant Mass. As in his other works, he masterfully drew from the everyday speech and local cultural manifestations. Mejía Godoy made a call to all musicians to work together to create the mass, but only Pedro Pablo Martínez, “El Guadalupano” responded. Martínez’s song, the Meditation section of a mass, evokes the countryside and its closeness to nature using a theme of bird calls — in the recording studio the musicians accurately imitate them to open the song. A group of Miskitu people from the Caribbean coast added one Christian religious folk song in their language. In the recording Mejía Godoy included many types of traditional repertoire, such as brass bands performing raucous music never allowed inside a church for the celebratory Gloria. In everyday life, however, congregations sang the mass with what they had, guitar accompaniment. The mass was first held in 1975 in a small adobe church in Solentiname, a small Liberation Theology community in the south of the country. The first public celebration of the mass in the capital city Managua two years later was violently broken up by Somoza’s military and the conservative church hierarchy banned it outright, but printed lyrics circulated widely underground and the mass grew in clandestine popularity. The 1979 overthrow of the dictatorship allowed for a full 1980 studio recording with a wide variety of instrumentation that corresponded to the differing styles that Mejía Godoy used to try and represent all of the nation’s musics. The mass not only attained lasting popularity in Nicaragua but has been translated and celebrated throughout the Americas, even sung in several U.S. Protestant churches.

One part of the mass, the Credo (I Believe, in Latin) , became popular on its own and has been rerecorded in many languages throughout the world. In this section of the Catholic mass attendees straightforwardly state their Christian beliefs. Instead of the usual memorized sentences for this and other parts of the mass, Mejía Godoy drew from his keen observations of daily life to celebrate and dignify common working people. This appreciation of the spiritual nature of everyday life related to the movement of Liberation Theology growing throughout the 1960s and 70s that advocates for Christians to exercise an “option for the poor.

Compare this recording of La Misa Campesina Nicaragüense with an electrified pop version named La Misa Campesina that was recorded in Spain in 1978. Listen also to the almost entirely son nica-based Misa Popular Nicaragüense versus the variety of regional styles used in the Misa Campesina Nicaragüense. You may enjoy other songs by Carlos Mejía Godoy, as well as his younger brother Luis Enrique Mejía Godoy. One of Carlos’s sons plays a marimba in the contemporary Nicaraguan band La Cuneta Son Machín (Sidewalk Sound/son Machine) that punks up traditional songs and their own high speed compositions

Ricardo Arjona is faraway the best-known musician from Guatemala. He has had tremendous success, earned two Grammys and sold over 20 million records. He began as singer-songwriter dedicated to general romantic topics and in the mid 1990s expanded his lyrics to deal with social themes as an aware singer-songwriter, much in the vein of Carlos Mejía Godoy. Based on Guatemalan musics one would not guess his nationality, he draws from Latin rock and pop, Cuban dance styles and lately the Tejano/Norteño genre — but passed over marimba music, the most identifiable musical marker of Guatemala that remains limited to that country’s national market. Arjona first found success as a romantic singer on his second album released in 1988, Jesús, verbo no sustantivo (Jesus, Verb not Noun). The poignant lyrics and Arjona’s compelling singing style made it a major success throughout Latin America and among the Latino population in the United States. Like Carlos Vives of Colombia (see below) his musical career was boosted by his role in a telenovela (soap opera.) He fully came into his own in 1996 with Si el Norte fuera el Sur (If the North were the South); the title track indicates his new exploration into socially relevant lyrical material on the album

The Garifuna, or Garinagu people dot the eastern Caribbean coastline from Belize to Nicaragua. They have a unique history different from other African-Central Americans. Kidnapped from West Africa and taken to the Caribbean island of Saint Vicent, the enslaved people gradually mixed with the local Amerindian indigenous population. After a successful rebellion that expelled the British, the colonizers returned and in 1797 dumped the “Black Carib” population onto the small island of Roatán, from where they spread out along the coast. Garifuna music ranges from deeply African drumming to guitar-based ballads, but is primarily known outside the community for the popular dance music punta. In the 1990s this style, with its African-based sensual dance, became very popular in Honduras. It spread to international audiences with the massive success of “Sopa de caracol” (Conch Soup,) a punta song by a Garifuna composer of Belize redone by the Honduran mestizo group Banda Blanca, with a mix of Spanish and original Garifuna lyrics. In the early 2000s one of the most accomplished musicians, Andy Palacios, seemed poised to become a major World Music star when he tragically died young. His album Watina showcases his commanding blend of acoustic folk and dance styles.

Panama remained a Colombian province until the United States literally created the country in order to occupy it and construct an inter-oceanic canal. Finished in 1914, the canal project attracted large numbers of Jamaicans and Trinidadians laborers who reinforced Afro-Panamanian elements of the nation’s culture. One of the first stars of modern reggaetón was Panamanian El General (Edgardo A. Franco). Other Panamanians made their mark in New York earlier during the explosion of salsa in the 1960s and 70s. The best known of these is Rubén Blades, a greatly admired composer, singer and band leader. He revitalized salsa towards the end of its “boom” with lyrics that spoke to social issues and ethnic and national pride. When the height of salsa’s popularity subsided, Blades relaunched his career with music that reflected his renewed interest in his home country. Eventually he even ran for president in 1994. Though unsuccessful, he later served as Minister of Tourism 2004-09.

Blades’s return hit was a cover of “La Rosa de los Vientos” by the talented singer-songwriter Rómulo Castro. Castro has composed and performed in politically oriented New Song groups, his current and most enduring being Grupo Tuira (a river.) Just as Panama is a crossroads of many cultural influences, Rómulo Castro draws from a wide palette of musical styles. His lyrics can stand alone as poetry; their beauty defies foreign translation. In fact, for his international rerelease Rubén Blades reworked a good part of the lyrics below to be more broadly accessible – or more pedestrian, depending on one’s point of view. The song was composed just after the United States military invasion that overthrew corrupt general Manuel Noriega, once a close ally of U.S. intelligence services. Most Panamanians were glad to be rid of Noriega but regretted the lack of U.S. support for earlier Panamanian resistance to him and the invasion’s indiscriminate destruction. As referenced in the song, entire working-class neighborhoods in Panama City were targeted. A Grammy winner and a hit throughout the continent, the lyrics of “La Rosa de los Vientos” appealed to many concerned with national and regional sovereignty.

Regrettably, at the time of their release CDs by Rómulo Castro were difficult to obtain outside of Panama. He now has a YouTube channel that includes a live version of this song with added instruments. The album by Rubén Blades on his Grammy-winning CD La Rosa de los Vientos features songs by other Panamanian composers

The historical record of music in the Euro-classical tradition, much of it housed in churches, has suffered from the destruction of earthquakes and the ravages of wars following the independence struggles of the 1820s. Central America still lags far behind most of the continent in careful, systematic research on all types of music; hopefully more scholarship will appear in the future. Spanish Colonial authorities’ efforts to reproduce Europe’s elite music favored Guatemala, the center of political authority for the isthmus (outside of Panama, governed from Bogotá) and the largest church organs and ensembles developed there.

In the mid-19th century, secular compositions and the first conservatories dedicated to the classical idiom began to appear. Composers with some formal training typically wrote sacred works for church ensembles, especially choruses, and sacred and secular works for brass and wind bands. These bands featured the best trained musicians within their respective countries and often developed over time into symphony orchestras. One of the most important brass bands has been the Honduran Banda de los Supremos Poderes (Band of the Supreme Powers.) Its fame throughout the region was established by composer and director Manuel Adalid y Gamero (1872-1947) and it remains a leading ensemble.

As Central Americans had little contact with contemporary compositional practices in Europe, waltzes and other dance forms typify the secular works of the latter nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Nicaragua is a representative example. Like others of his generation, José de la Cruz Mena (1874-1907) adopted a European academic style reminiscent of Haydn for his masses, but his most famous pieces are instrumental waltzes like those of Strauss. Band and chamber orchestra director Pablo Vega Raudes (1850-1919) founded the nation’s first school of music. His son Alejandro Vega Matus (1875-1937) wrote sacred masses and led the most celebrated dance and orchestral band of the day, a vehicle for his many fox-trots, one-steps, pasodobles and other songs.

Symphonic orchestras have suffered from a lack of consistency, forming, disbanding, and reorganizing according to the vagaries of government and upper-class financial underwriting. However sporadic their existence, symphonic orchestras and the gradual expansion of formal musical education spurred nationalist compositional currents. Almost all composers relocated for a time to Europe to advance their studies, then relied on their own research into local folk music for nationalist material. For instance, the most prominent early nationalist composer in Panama, Narciso Garay (1876-1953), was also one of the nation’s most prominent folklorists. Unhappily, the embryonic state of ethnomusicology and folklore research has often led composers to a very uneven and often erroneous grasp of traditional music. Salvadoran Maria de Baratta (1894-1978) and Nicaraguan Luis A. Delgadillo (1887-1962), for instance, studied in Italy and upon returning based several works on both imagined Indigenous music before 16th century contact and at times not so rigorous or careful collection of contemporary groups of high-Indian heritage. De Baratta deserves credit not only for being a pioneering woman leaving the domestic role assigned to women, but also for directly engaging as someone with upper-class status with the reduced communities identified as “indio,” of high Native American heritage. All things “indio” continued to be disparaged and marginalized after The Matanza, and her investigations were a courageous move after which little has been seriously researched. She published a book with transcriptions of traditional music interlaced with some highly speculative conceptions of pre-Contact musical culture and its supposed survival to modern times. Her and even more so Delgadillo’s notions of Indigenous musics may have suffered from inaccuracies, but that did not hinder the music’s acceptance in some elite circles: their fellow middle-and upper-class audience members were so not interested in actual authenticity as demonstrating that their country was just as capable of creating a national elite style as the rest of the world. The same was true of Guatemala’s salient composer in the first half of the twentieth century, Ricardo Castillo (1891-1966.) He wrote several short orchestral works of nationalist character inspired by Mayan religion, sometimes integrating actual melodies and rhythmic sensibility.

Many composers in the European-based classical tradition continued conservative approaches that harked back several decades, but more recent compositions parallel the most avant-garde cosmopolitan currents. Guatemalan Joaquín Orellano (b. 1937) is one of the region’s most original composers. He experiments with the sonorous possibilities of the marimba and created several unique instruments that he integrates into non-tonal and minimalist compositions, sometimes combined with electronic tape. His crescent-shaped imbaluna combines “im” from “marimba” and “luna” (moon.) His ciclo im faces keys inwards, so that when spun a ball randomly hits the inverted keys.

Other major composers include Salvadorans Gilberto Orellana Sr. (b. 1921), the first Salvadoran to use serial techniques in the early 1960s, and German Cárceres (b. 1954) who led the national symphony for many years; Hondurans Sergio Suazo Lang (b. 1956), pianist and composer; (1917-1989) founder and director for many years of the Juan Manuel Mena Moreno Nicaraguan National Chorus, whose creative settings of folk music remain well known. Panamanian Roque Cordero (1917-2008,) remains probably the best known Central American composer (in part because he relocated to the United States) and one whose non-nationalist work is most easily available.

Colombia constitutes the northwest corner of South America, almost twice the size of Texas (at 440,000 sq. mi.) Its contrasting geographical zones can be grouped into five major regions (presented from northwest to southeast): 1.) The Pacific coast, a tropical lowlands west of the Andes mountains. Historically isolated, its heavily African-descent population is famous for marimba-centered music and dance (see Chapter 8). 2.) The Atlantic/Caribbean coast, known simply as La Costa. It contains the nation’s beach destinations and the city of Cartagena. Its population is of mixed European, African, and indigenous ancestry. 3.) The Andes. Agricultural and industrial production, political power, and a majority of the country’s population are located in the central Andes, which is primarily European and mestizo. The capital, Bogotá, and major cities of Medellín and Calí are all found in this region. 4.) The Colombian Amazon, in the far south, is a tropical lowlands populated with isolated Indigenous groups. Over 100 distinct Amerindian languages are spoken within Colombia, most in the Amazon region. 5.) The Llanos or prairie, in the southeast (see below). Colombia’s total population of nearly 53 million is estimated to be approximately 50% mestizo, 26% fully European, l4 % strongly African descent mixed mulatto, and 10% clearly Indigenous.

During the colonial period the Spanish invested significantly more in what is now Colombia than in neighboring Venezuela. The discovery of gold and other valuables in Colombia supported the development of European musical practices in the churches of Bogotá and Cartagena, while Venezuela received less attention. Most of Spanish-speaking South America broke ties with Spain in the early 1820s during prolonged wars of independence, led by Simon Bolívar and other European-descent elites. Bolívar’s dream of creating a Greater Colombia failed, but Ecuador, Colombia and Venezuela still recognize an affinity, as evidenced in their similar national flags. Independence soon consolidated emancipation for African-descendant slaves, though economic systems in both countries concentrated resources in the hands of a small ruling class.

Colombia has received comparatively little immigration since independence due to the general weakness of its economy. Coffee exports represented the only source of modest export revenue through the 1970s, and much of the rural population still lives in poverty. Attempts at socioeconomic reform literally died with the assassination of progressive politician Jorge Gaitán in 1948. His murder plunged Colombia into a protracted civil and ideological war, often referred to as “La Violencia.” Although the social actors and organizations have changed and mutated, to a great extent the same socioeconomic contradictions continue into the present.

Both the once-populist guerrilla movement and military-dominated governments were corrupted by the tremendous revenues generated through cocaine and heroin production. Despite growth in industrialization and agricultural development, drug production has had an outsized influence on politics and the national economy. Struggles to control the supply of cocaine (to satisfy demand in the United States) have hampered Colombia’s democratic process and led to terrible violence, at first mostly committed by the military and its affiliated “civilian” para-military units but increasingly over time also by corrupted guerilla groups. Sophisticated transnational networks now control coca-rich regions, prioritizing business goals rather than political ones. Similar to how the U.S. mafia’s activities underwrote the flowering of dance music in Havana, Cuba until their ouster with the 1959 revolution, the dark clouds of expanding narco cartels in the 1970s onwards also bore a kind of “silver lining” in a lavish spending of their new riches on musicians. For example, the “narco economy” contributed directly to the spread of vallenato music (see below) and later the salsa “boom” in Cali, with drug lords frequently sponsoring their favorite artists or groups. In fact, it can be reasonably argued that the faster tempos of Cali salsa bands correlated to omnipresence of cocaine. In recent years there have been hopeful signs of alternative development. For instance, the city of Medellín, once considered a dangerous haven for the narcotics industry, now boasts a series of improvements, from gondolas that help to integrate the poorer areas with the rest of the city to other local improvements. The result is a substantial increase in international tourist trade. The African-Colombian population has achieved some greater national visibility and positive recognition, as evidenced in the political realm by the current vice-president, Francia Márquez, breaking ground as the first African-Colombian woman to reach such a high office.

If one had to single out the one Colombian musical form that has achieved the widest international popularity it would have to be the cumbia. The basic commercial version is easy to master, and the music so infectious that for many decades, in its various local interpretations, it reigned as the dance music of choice in Mexico, most of Central America, and Peru (there renamed “chicha“, see Chapter 8).

The traditional cumbia sounds quite different, though its African-based rhythms have informed all subsequent permutations of the genre. The traditional dance is performed at night by couples standing in a circle around the musicians. Women illuminate the scene with bundles of candles wrapped together in cloth. The folk ensemble conjunto de gaitas has been the touchstone for several transformations into various modern styles. This ensemble clearly demonstrates the tripartite Indigenous, African and European cultural formation of the Caribbean coastal area of Colombia. The flutes are of Indian origin; the drums are of African derivation; and the language of any lyrics used, and the music’s melodic form and tonal harmony, trace back to Europe. The term gaita refers to a flute, a musical genre, and also a traditional ensemble. Some 20th-century urban popular music continues to be called gaitas, but most of the music derived from the conjunto de gaita, together with other styles from the Atlantic Coastal region, are now subsumed under the umbrella term cumbia.

The conjunto de gaitas consists of two long, vertical gaita flutes made from cardón, a type of cactus tree. The ones heard in Listening Example 4.4 are gaitas largas, almost three feet long. Players blow across a quill from a turkey, carefully embedded in a mass of beeswax mixed with some ground-up coal on the top end of the flute. The sound is breathy, rich with many overtones. The gaita hembra (female) traditionally has five holes about halfway down the flute, and the slightly longer (and therefore lower-pitched) gaita macho (male) two holes. Modern urban gaita flutes often substitute other materials and may employ electrical drills to make the holes, but the beeswax is a necessary ingredient. The gaita hembra takes portions of the melody that the gaita macho complements by doubling or contrasting, with the two flutes exchanging short phrases back and forth. In traditional ensembles the gaita macho players also played the maracas with one hand, but now a separate musician plays maracas. The maracas are filled with dried seeds and can be made from large gourds or from metal or bamboo tubes

Cumbia percussion comes from three distinct kinds of drums. The tambor llamador, as its name implies, “calls” by holding the group solidly in rhythm with a consistent pattern. It has a single head, is cylindrical in shape, and the drummer holds the drum horizontally on his lap. The tambor alegre (“lively drum”) offers the greatest variety of pitches and is around two feet long in a cone shape, not unlike the famous Cuban conga drum. As the name implies, the tambor alegre improvises the most< and often enters into a dialogue the gaita hembra. The tambora, the lowest pitched, is a large double-headed drum usually supported on a wooden stand that is hit with drumsticks on the heads and the shell. This drum has a deep, bass sound, and represents a more recent addition to the ensemble.

For decades Los Gaiteros de San Jacinto have been the best known conjunto de gaitas in Colombia. They formed in the 1930s in the region known as Montes de María near the Caribbean. Folklorists first helped to promote them in the 1950s, and they toured internationally and made recordings that cemented their national status. In recent years Los Gaiteros have obtained more international success as a World Music group. This international recognition has helped inspire a revival of interest in traditional gaita music among urban performers and audiences in Colombia, the most influential example being Carlos Vives (discussed below).

The lyrics of the title song of their album Un Fuego de Cumbia (Cumbia Fire) refer to laments, for the conjunto de gaitas traditionally perform for funerals as well as dances. The singer mentions the combination of ethnicities that form Colombian culture, with stereotypical attributes for each: animated African influences from the drums and “passive” (stoic) Indian melodies on the flute. The phrase “sangre pura” (pure blood) references both the connectedness of the population through bloodlines as well as the strength and courage it takes to survive in this zone of armed conflict.

Fighting and landmines have endangered farming and even the harvesting of the cardón to make flutes

As in many other parts of Latin America and the Caribbean, urban military brass and woodwind bands in the latter half of the 19th century inspired similar ensembles in Colombian towns and small cities that adapted local musical forms into new formats. The first to achieve national diffusion was the bambuco, labeled at first simply “canción colombiana” (Colombian Song.) This music transformed guitar and other string instrument repertoire from the country’s interior into arrangements appropriate for large bands that performed in city ballrooms. In the 1930s and 1940s, the predominantly European-descent upper and middle classes in Bogotá and elsewhere found the reworked bambuco easier to accept than music from the African-influenced coastal regions. Ever-larger orchestras incorporated non-Colombian styles into their repertoire such as waltzes, fox-trots, and tangos. By the 1940s musicians began incorporating Caribbean dance music influences as well (mambo, son, merengue) and increased the size of ensembles to become like jazz orchestras in the United States, and elsewhere. These influences helped smooth the way for the successful adaptation of the Afro-Colombian coastal porro, which is rhythmically quite similar to the cumbia, followed by acceptance in elite circles of other dance band transformations of traditional.

By the 1950s these Afro-Atlantic Coast forms had become the most popular form of national dance music and collectively were termed música tropical. Lucho Bermúdez led one of the most innovative and successful orchestras of this type. Dressed in suits or swanky uniforms and following careful arrangements, Bermúdez’s band and those of others helped to make coastal music suitable for “high society” ballrooms and social clubs.

While Afro-Cuban popular music impacted música tropical, the repertoire was undeniably Colombian and featured the smooth sound of the woodwind section (imitating traditional reed instruments.) In the following selection, “Gaita de las Flores” (Gaita of the Flowers), note how the horn section often plays repeated short phrases, a trait taken directly from the traditional cumbia as heard on the gaita flutes in the previous example.

By the 1970s, salsa music — the “New Yorican” transformation of Cuban popular dance music — quickly expanded to four principal cities: New York; San Juan, Puerto Rico; Caracas, Venezuela; and Cali, Colombia, the last sometimes self-promoted as the “salsa music capital.” Some of the biggest names in salsa — Joe Arroyo, Fruko sus Tesos, and La Sonora Carruseles — have come from Colombia and orchestras continue to flourish there.

The origin of vallenato is contained in its name: “nato” – born in, “valle” – valley. This hugely popular music and dance form emerged as a distinct style around the 1940s in the city of Valledupar, in the rural northeast region. A typical early vallenato band consisted of a button (not piano keyboard) accordion, a small single-headed drum called caja (literally, box) and a guacharaca, a scraper usually made from a dry gourd. Around the 1970s vallenato bands added an electric bass, and this quartet created new versions of traditional Colombian music, including cumbia. Unlike some música tropical, lyrics are an indispensable element in vallenato. The lead singer is always joined by another who harmonized a good part of the song in 3rds. Lyrics include themes of romantic heartbreak, leavened with some of the joys of falling in love, as well as an oral tradition that chronicles the lives of people in Valledupar. Two common genres performed by vallenato groups are the merengue in 6/8 meter and the paseo in 4/4 meter (see below.)

During the heyday of música tropical, most of the nation disdained vallenato as the music of hicks from the countryside. Nevertheless, it slowly gained popularity, also crossing the border to become a favored style in western Venezuela. Rafael Escalona’s compositions and talent helped expand vallenato out of its regional base, furthered later by his portrayal in a blockbuster telenovela (TV series) by Carlos Vives. The popularity of vallenato throughout Latin America was enhanced from the geographical setting and many references to the music in the bestselling novels of Gabriel García Márquez, Colombia’s most famous and critically acclaimed writer. Some ensembles tried to expand their appeal by adding synthesizers and more percussion. Central to the music’s ascension was the rise of the marihuana industry in the region that expanded exponentially from the 1970s onwards. Drug cartels patronized bands and underwrote their recordings and tours. By the 1990s, vallenato began to eclipse música tropical nationally with talented band leaders as Diomedes Díaz, Binomio de Oro, and Lizandro Meza, the last an amazing accordionist and singer who broke into the international World Music market. Vallenato attracted a new generation when pop musician and actor Carlos Vives broke sales records with his rock interpretations of vallenato and other traditional forms, as discussed below.

The classic quartet of accordion, caja, guacharaca, and bass is still the mainstay of vallenato music. This is the format of the various groups that the Smithsonian-Folkways label recorded in 2008. It’s not surprising that one of the songs was “Cadenas” (Chains.) Composed by one of vallenato’s most respected composers, Rosendo Romero Ospino, whose popularity some people credit as the most important artist in establishing vallenato’s popularity on a national level.

A classic version of vallenato is “Cadenas” (“Chains”) by Ivo Díaz y su grupo, Listening guide 4.6 (Ivo performs another famous vallenato by his father, Leandro Díaz, who explains its inspiration here.) “Cadenas” is a vallenato-paseo, slightly modified with the addition of a repeated chorus, indicative of the plasticity of form of many modern vallenatos. The lyrics tie the composer’s feelings of despair from personal mistakes to the loneliness of the narrow streets in small towns in the northeastern mountainous region of Colombia.

The artists mentioned above remain very popular. For more recent vallenatos as well as a plethora of releases search YouTube for the seminal record label Discos Fuentes and Carlos Vives’s “rockified” vallenatos on Clásicos de la Provincia and El Amor de Mi Tierra discussed below.

Colombian musicians, always in competition the international Latin and Anglo pop music industry, received a huge boost when Carlos Alberto Vives Restrepo (b. 1961) turned his talents from portraying a vallenato musician on a runaway hit telenovela (TV soap opera) to concentrate on arranging and singing in a studio and on stage. Some vallenato purists were taken aback, but no one can deny that when Carlos Vives released his album Clásicos de la Provincia (Classics from the Provinces/Regions) it not only reminded Colombian musicians and audiences of the depth of their nation’s musical riches, it also introduced his reworking of vallenato and other Colombian genres to the rest of the continent in a tremendously successful way. The embrace by thoroughly urban audiences of musical sounds like actual gaita flutes showed that city dwellers now feel far enough removed from their rural origins to not fear losing social status from association with such music. Vives’s fusion of local forms with rock, pop and some Caribbean musical elements garnered Billboard and Grammy recognition and encouraged Colombians to draw from national sources for inspiration. Vives opened the door to compatriots Juanes and Shakira, both of whom composed in a similar stylistic vein before moving into more generically Latin American and North American crossover pop stardom respectively. Following Vives, the Latin American rock-en-español movement took off and groups around Latin America rode a new wave of creativity and commercial success. For more on this movement, and in particular international stars Shakira and Juanes, see the section _”Contemporary Latin American Popular Music Colombian Hit-Makers: in Chapter 10.

After subduing the Indigenous peoples and suppressing their musical life, Spain transferred both their elite and popular musical practices into the Nueva Granada colony, what would become independent Colombia. For the church-based music the early 1600s Bogotá’s cathedral boasted the largest collection of written music in the Americas. This efflorescence in the religious realm of the European art tradition continued apace for a century, when it began a slow decline. By the 1820s, church organs were in disrepair, and few professional singers could be found. The rest of the 19th century saw the slow development of secular Euro-classical music, overwhelmingly centered in Bogotá. Early attempts at nationalist composition by José María Ponce de León [link in Spanish] (1846-82), like pieces based on bambucos, failed to generate widespread interest.

Only as the 20th century progressed did determined efforts at institutional European classical education begin to bear fruit. Guillermo Uribe Holguín (1880-1971) founded the Orquesta Sinfónica Nacional (National Symphonic Orchestra) in Bogotá in 1936, and conservatories and permanent performing ensembles established themselves in Cali and other cities. Uribe Holguín studied with the Panamanian composer Narciso Garay (_link to CAm section ref.). His work, strongly influenced by studies in Paris, has recently enjoyed a certain revival. A notable composer in the latter 20th century is Jesús Pinzón Urrea (a short Spanish-language biography here) (b. 1928-2016), founding director in 1967 of the Orquesta Filharmónica de Bogotá, currently the most prestigious Colombian symphony. He has written pieces without set forms and using chance composition (see Appendix). He also attempted to adapt Indigenous music from the far south Amazon, most famously in his work for chorus and orchestra Goé Payarí of 1982.

There are many active contemporary composers and most experiment with integrating national musical material. Blas Emilio Atehortúa (1943-2020), who studied with Alberto Ginastera in Argentina, gained international attention especially through film scores, notably for Oedipus Mayor (1996). Francisco “Pacho” Zumaqué (b. 1945) must be one of the continent’s most eclectic musical talents: he first worked with his father’s Afro-Caribbean band and wrote the pop-salsa hit “Colombia Caribe” that was chosen as the theme song for the national soccer team. He composed electro- acoustic avant-garde pieces but is most well-known for combinations of popular themes and rhythms in classical orchestrations, such as Fantasía Caribe recorded in various instrumentations. Luis Pulido Hurtado [link in Spanish] (b. 1958) twice won the annual Ministry of Culture’s composition prize, in 2006 with a woodwind quintet entitled Diosa Chía, named from a mythical female figure of the Indigenous Chibcha people. Representative of his general style is the chamber orchestra piece “Tete Malkutak.” The dedication of composers and performing musicians has maintained this tradition despite the historical shortcomings of financial support necessary to more fully expand the understanding and popularity of this genre.

The Llanos qualifies as a bi-national region with an identity all its own. “Llano” means flat, and the associations with this large swath of plains parallel those of the mythic West in United States culture. Like the U.S. “Old West,” and like the broad pampas in Argentina, historically the main occupation in the Llanos has been cattle raising. The Llanos region, however, floods during the rainy season and cowboys with water all the way up to the bottom of their horses have to herd cattle onto dry areas where they feed. Ethnically, llaneros (Llanos residents) are a mixture of peoples of European, Indigenous and African descent, the last including many escaped slaves that made their way from the coastal plantations south to freedom in the distant Llanos. In Colombia and Venezuela, mestizo refers to any combination of this tripartite ethnic make-up.

Though an important region in Colombia as well, the Llanos hold a special place in the Venezuelan imagination. In the 20th century Venezuela’s elite promoted the Llanos as a touchstone of national identity. As the nation urbanized, images of open land and rugged individualism comforted those moving into concrete buildings with city noise and pollution. To this day, the novel Doña Bárbara, set in the Llanos, is required reading for all Venezuelan high school students. Música llanera has played a role similar to that of country music in the U.S., closely associated with an earlier, more rural time. Overall, it remains the genre most commonly identified with Venezuela.

The hallmark music from the Llanos is the joropo llanero genre, also known simply as música llanera. The word “joropo” probably stems from the Arabic “xörop,” the same root for the English word “syrup,” a reference to something sweet and pleasing. Writers in the early 19th century used “joropo” to describe celebrations with music and dancing. Currently the term references specific musical styles and the couple dances that accompanies them. Note that there are many forms of joropo in Venezuela, but the principal one is from the llanos region.

Joropo llanero instrumentation consists of a singer, a four-stringed cuatro (not to be confused with the Puerto Rican cuatro; see Chapter 5), maracas, and the arpa llanera, a 32-stringed harp. The cuatro is strummed in a quick, fast manner, not plucked (further discussed below.) Joropo maraca players are probably the most virtuosic in the world. They often hold a pair of small, high-pitched maracas vertically and execute complex rhythmic improvisations, moving their arms in an amazing display. The harp is a diatonic instrument, derived from folk instruments brought by Spanish settlers. Its strings were made originally from animal gut but now are of plastic. Harpists play a bass line on lower strings with their left hand and chords or melodies simultaneously with their right, often using both hands melodically during solos. Recently, performers have added an electric bass guitar, and sometimes the larger guitar-like bandola also joins in, but the basic iconic quartet continues to represent llanera culture.

Joropo llanero music is in a 6/8 or 12/8 meter, usually at a moderate tempo, but sometimes very quick and therefore musically challenging. Singing is prominent in this style, with lyrics often recounting historical events in a manner similar to that of Mexican corridos (_see Chapter 3). Vocals have a high, pinched, nasal quality. A true llanero singer must not only have an extensive repertoire of memorized songs, but most importantly be able to improvise four-line coplas (rhyming sets of verses) on the spot. There are a good number of female singers, but this is a male-dominated tradition. Like the desafíos, vocal duels between two singers of central and southern Spain, and like the acerbic commentary in traditional music from western Africa (and therefore like rap), an accomplished llanero singer locked in competition with another singer will try to “one up” his compatriot with biting comments. Hailing from an impoverished small town in the western Venezuelan Llanos, ex-president Hugo Chávez Frías grew up in such an environment that prized verbal dexterity. During the 200s and 2010s he publicly sang joropos, a proud acknowledgement of his humble roots that valorized a tradition no previous president would “stoop” to associate themselves with.

Singer-songwriter Reynaldo Armas is one of the best known and most prolific masters of música llanera. His first album in 1977 launched his popularity.

The song “Indio” was a major hit for Armas and speaks to the pride people of the plains maintain in their mestizo heritage. The majority of joropos llaneros are in a major key, though many are in minor like this example. Armas chose this slow tempo and minor key because of the contemplative nature of the lyrics. Notice how at the beginning of section B he declaims several lines using only two or three notes, almost like talking. Sometimes singers emphasize this technique when improvising, especially in duels with other singers. This composite video integrates a good feel for the nature and people of the llanos with a short clip of Armas singing the song much later in his career.

The joropo llanero continues to be very popular in this co-national region with a constant replenishment of new talent. Venezuelan Emily Galaviz, like many popular music artists, first came to the nation’s attention from a TV talent show in 2022 when she was only 15 years old. She released many successful singles and had a breakout hit in 2024 with a medley of some of these famous joropos llaneros simply titled “Popurrí 01.” Her YouTube video brought millions of views despite its rather barebones production of singing in a studio. The video for “Yo sí sé” (Yes I Know, or I Know For Sure), her most recent as of this writing (released August 30, 2025), gives more of a feel for the Llanos region and especially celebrates llanera women

There are a multitude of other videos under “música llanera” or “joropo llanero” on YouTube. One of the most important is singer songwriter Simón Díaz (1928 – 2014) who helped establish the genre’s enduring popularity in Venezuela. The album Sí, soy llanero: Joropo Music from the Orinoco Plains of Colombia contains relatively recently recorded Colombian musicians and demonstrates how identical the style is across the two national borders.

Venezuela, about twice the size of California (352,000 sq.mi.), is one of the most ecologically diverse nations on the planet. The continents of Africa and North and South America first separated along a line in the spectacular southeast region where today tepuis, tropical mesas, still yield new discoveries of plant and insect life (this region inspired the book The Lost World.) The southeast is inhabited by scattered Indigenous groups and a stream of tourists that flock to see Angel Falls, the earth’s tallest waterfall. The far southeast overlaps with Amazonian Brazil. Venezuela’s immense southern Llanos make up over a fourth of the country, shared with Colombia to the west. The northern end point of the long Andes Mountain range descends in western Venezuela and is sometimes called The Tropical Andes due to the high humidity from the Caribbean weather environment that reaches over 6,000 feet. This area provides vegetables from small farms cultivated by people of European and Indigenous descent. In the far northwest of Venezuela lies Lake Maracaibo, the largest freshwater lake in South America, that rests atop now mostly depleted oil reserves that generated immense wealth in the 1900s. A strong African-descendant presence remains in several towns around the lake and has contributed to racial mixing in the nation’s second largest city, Maracaibo. Other heavily African-Venezuelan pockets dot the northern coast where cacao has been cultivated, the largest and most famous being the eastern Barlovento area. The Indigenous Wayu’u live both in the arid Perijá peninsula, shared with northeast Colombia, and in the northern neighborhoods of Maracaibo. The bulk of the population of over 28 million lives in the northern third of the national territory and is one of the most urbanized in the world at 93% (compare with 74% of Colombians.)

Venezuela takes its name from the Amerindian houses on stilts that reminded the first Spanish of Venice. The colonial era brought only slow economic development to this region, mostly agricultural. Simón Bolívar (1783-1830), known as “The Liberator,” was born into wealth and a slave holding family. Eventually he realized that emancipation was key to mobilizing the African-American and mixed-race population against Spain He allied with the fierce mestizo horsemen of the Llanos who carried the day in the final 1821 clash with Spanish colonial forces. The landed aristocracy, however, soon reasserted control, marginalizing other groups from power. Despite various rebellions since independence, near-feudal conditions continued until oil was discovered in the early 20th century. Oil production generated considerable revenue. Sadly, for the bulk of the population the newfound wealth circulated only among a small professional class while successive dictatorships perpetuated one of widest economic gaps between rich and poor in the Americas.

Several campaigns in the 20th century to “whiten” the nation succeeded in attracting (in order of number) Spaniards, Italians, Portuguese, and (Christian and Muslim) Lebanese to Venezuela. The creation of affluent mini-cities surrounding oil production sites created and run by United States companies contributed to a sense that the nation was advanced and cosmopolitan, and in this way exceptional to much of Latin America. The United States culture in these “oil cities” impacted Venezuela’s sociocultural reality (see Tinker Salas’s insightful study The Enduring Legacy.)

In the realm of culture, the Venezuelan upper classes, more than some other national elites, eschewed local popular culture for symbols of national identity and favored an orientation towards ideas of Western modernity, especially in the visual arts. Cutting-edge architecture gave a modernist look to new construction in Caracas. One side effect relevant to music is that this oil wealth allowed the pioneering ethnomusicology couple Luis Felipe Ramón y Rivera and Isabel Áretz (originally Argentinian) to systematically document many musical traditions, a rich archive still active today. In the 1980s through the 2000s they were able to host an intensive training workshop for music folklorists and ethnomusicologists from throughout Latin America, the only continent-wide initiative of its kind. Caracas also became a magnet for the nation’s impoverished who constructed shantytowns in the surrounding hills. At night, hundreds of thousands of light bulbs continue to twinkle from small houses and shacks on the periphery of the capital city. In the latter years of the decade of the 2000s a government program gradually allowed for the substitution of energy-saving LED lights throughout these communities, actually changing the color of the hills at night. It is a captivating sight, but also a visible indicator of still-disproportionate divisions of wealth

Economic “neo-liberalism” involves the privatization of public institutions and industries which better fits a new model of globalized corporate capital. Beginning in the 1970s the developed world increasing imposed neoliberalism on Latin American nations, including Venezuela. These policies resulted in declining living standards for the majority. In Latin America this worldwide scheme met its first serious public challenge in Venezuela in 1989. The newly elected government had promised to change the neo-liberal economic direction, but when it reversed course and drastically raised prices on public services a huge rebellion erupted in Caracas and elsewhere. Though disturbances ended in a few days, the government ordered military reprisals in poor residential areas and a series of massacres resulted. Called the “Caracazo,” this violence spurred a mass movement that eventually elected a charismatic candidate, Hugo Chávez, president in 1998. Among other things, the new constitution overwhelmingly approved in 1999 guaranteed some key Indigenous people’s rights and that the nation’s material wealth could not be privatized. In 2002 a right-wing coup overthrew the government and dissolved all elected offices and the judiciary; the U.S. government immediately recognized the new ruler. But a massive outpouring of grassroots support dismantled the conspiracy within 48 hours.

A mobilization and conscientization of the popular classes characterized the Chávez administration that lasted through 2012. The renamed Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela was successful in reviving OPEC, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, and global oil prices returned to more profitable levels. Oil revenues, an overwhelming factor in the nation’s economy, were redirected into a series of social programs that sharply reduced poverty. This period saw many improvements in the national infrastructure, from building sewage treatment plants to free medical and dental clinics and new universities. Venezuela passed through a unique era: the desperately needed social services existed side by side with an entrenched ruling class without a significant transformation of the existing economic system, together with a modernized voting system ex-U.S. President Jimmy Carter called the best his election center had monitored. One sociocultural change that effected music was a challenge to the previously little questioned myth that “there is no racism in Venezuela.” The new empowerment of the darker-colored majority brought racist attitudes out into the open and led to more discussion of the topic.

Hugo Chávez died from cancer in 2013, and unfortunately for Vice President Nicolás Maduro the price of oil plummeted the next year. Public and private corruption has been a problem that has troubled almost every Latin American nation, but perhaps the single large source of oil income has made it even more damaging throughout Venezuela’s history; there appears to be little or no progress on this front so far this century. While the United States government was always hostile to the model of social welfare that Venezuela began to offer, diplomatic and media attacks were now joined by devastating open economic warfare. Under the more innocuous name of “sanctions” the many times more powerful U.S. so dominates the world’s financial systems that a targeted country’s economy can be systematically destroyed; the plight of Cuba is a revealing example. Between 2012 and 2020, Venezuela suffered the worst peacetime economic contraction in the world since 1950, overwhelming a result of U.S. economic sanctions. Social programs were eviscerated. Most of the medical clinics have simply disappeared. Funding dried up for initiatives that aided local music and musicians. The deadly sanctions account for the loss of thousands of lives. Where historically Colombians emigrated to Venezuela for higher paying jobs, the accumulated economic effect of this economic warfare has reversed the trend, leading to a huge out-migration of Venezuelans to many countries, especially to the United States that up until the recent Trump presidency gave preferential treatment to both Cuban and Venezuelan immigrants.

No elections can be fully democratic if a foreign power wields enormous economic and military power, and announces, both openly and more covertly, what the election results should be. Like so many national elections in Latin America, the Venezuelan national elections in 2024 were held in such circumstances. While both sides claimed victory at the ballot box, it’s most likely that Maduro lost at the ballot box from a protest vote. How would the population choose if the U.S. economic war ceased, even for a year, and then elections were held without threats of a return to outside interference? It’s doubtful we will ever know. It is certain, though, that whatever the political leadership, peaceful and equal relations between Caracas and Washington would drastically improve the unfortunate plight that continues to beset the Venezuelan nation

Heritage from Spain remains vital in the great variety of folk forms within the nation, though of course many genres have changed over time from interaction with African and Indigenous aesthetics, and traditions vary widely. In the Tuy valley region just south of Caracas, for instance the joropo tuyero uses a harp with metal strings that produces a completely different sound from the joropo llanero. The cuatro is not used, and song lyrics incorporate a complicated Iberian rhyming scheme. The hilly state of Lara, between Lake Maracaibo and Caracas, is often thought of as the most musical region of the country. The best cuatros are handcrafted in Lara, and some cuatro variants have additional strings. The Spanish-derived cuatro is so widespread within Venezuela that it is considered the national instrument.

One of the numerous song forms that utilize a cuatro is the polo, distinct from the Spanish flamenco variant of the same name. Polo is found in the far northeastern state of Sucre, named for José Antonio Sucre, a young compatriot of Bolívar. Listening Ex. 4.8 “Los Dos Titanes” (The Two Titans) is a polo sucrense (from the state of Sucre) written in the early 20th century and still well known. Polos are characterized by a moderate tempo in 3/4 or 6/8 meter. Their accompaniment consists of four sections that alternate between major and minor. The particular repeated pattern of “Los Dos Titanes” is shown in Ex. 4.4:

Daisy Gutiérrez is from the eastern part of the country and struggles to make a living as a professional musician. “Los Dos Titanes” comes from the album she and her husband produced themselves. She accompanies herself on the cuatro and has added a flute and mandolin played in a semi-classical manner. This type of arranged folk material came to prominence in the 1970s and is discussed below

You can find Daisy Guitiérrez on YouTube, where you can also find a version of “Los Dos Titanes” by María Rodriguez (d. 2014), one of Sucre’s artistic treasures who continued to perform into her late 80s.

There are other types of joropo in Venezuela with differing instrumentations but always with the essential common element of a quick 6/8 rhythm. The joropo oriental, the northeastern variant of the joropo almost always has a cuatro and the same smaller maracas together with various possibilities such as guitar, mandolin, violin, even accordion. ¡Y Que Viva Venezuela! Maestros del Joropo Oriental showcases some of the possible ensembles. A completely different type, the joropo tuyero, also called joropo mirandino or joropo central, is found in the mountainous Tuy region in the state of Miranda, found in center of the country between Caracas and the Llanos. Unlike the nylon strings (originally gut strings) on the arpa llanera, the arpa tuyera uses very distinctive thin metal strings and has larger sounding box to help amplify the sound. The result is evocative of a harpsichord, also metal-stringed. The lyrics often use an involved format that traces back to Spain. Most typically only two instruments, the harp and maracas, accompany the singer, who often is himself the maracas player. The vigorous dance style involves a couple that embraces and includes many spins, a totally unique dance style in the country. In 1974 the band 1,2,3 y Fuera (1,2,3 and Off They Go) substituted a keyboard with a similar tone, added an electric bass, saxophone and drum set and/or other percussion. They introduced this electric version of the joropo tuyero to new audiences in Caracas. After 13 successful albums they semi-retired, but came back in 2006 for several years with a younger keyboard player, Victor Morles, who has continued their tradition with his own group in Caracas

In depth