The Hispanic Caribbean is a vibrant area both culturally and musically. This relatively minor region with its small population has proven to be a cultural force rivaling or even surpassing wealthy countries of the developed world. Commercial music from Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Dominican Republic is now listened to around the globe. Of course, the Hispanic Caribbean supports many non-commercial forms of traditional African- and European-derived music as well. It boasts classical music performance, everything from music for the Catholic Mass to avant-garde electronic composition. And external musical influences from rap to flamenco continue to influence local practices, resulting in new hybrid forms.

In geographic and cultural terms, the boundaries of the Caribbean are difficult to define. The Atlantic coastal regions of South and Central America have a great deal in common with the islands discussed in this chapter. The music and lifestyle of Cartagena, Colombia, for instance, resemble those of Havana or San Juan much more than those of Bogotá. For this reason, scholars tend to refer both to the Caribbean as such and to the “circum-Caribbean” area as related. Recent years have witnessed massive numbers of Caribbean immigrants moving abroad to New York, Miami, Madrid, and elsewhere, further complicating notions of Caribbean geography. Several factors do tie the Caribbean together, however, related to the common experience of colonial domination and exploitation, as discussed in the introduction, and the gradual emergence of cultural forms in the context of West African slave labor.

Concepts of mestizaje or creolization are central to scholarship on Caribbean music. As discussed in the introduction, these terms refer to the fusion of different racial and/or cultural groups over time — in the case of the Caribbean primarily West Africans and Spaniards — and the creation of something new and unique. Mestizaje may be evident in the color of people’s skin and other aspects of their physical appearance, but it is also manifest in local languages, cuisines, religious expression, and in music. Of course, hybridized music exists side by side with other forms that may not be as hybrid, for instance music that continues to employ African languages or that derives from Spanish heritage, such as the música guajira tradition described below. One might conceive of a continuum of Caribbean music in this sense, with some genres more culturally blended than others; residents of the region move with ease among a dizzying array of different styles of music. After discussing the history of the Caribbean, this chapter provides examples of various styles of traditional music, then moves on to consider more fundamentally hybrid popular genres, and classical music.

Early missionary accounts tell us that several indigenous groups lived in the Caribbean when Christopher Columbus first sailed into the area, believing he was in Asia. Natives there included the Arawaks, Siboneys, and Taínos. Though most greeted the newcomers as friends, it quickly became apparent that Spaniards wished only to subjugate them. During the first decades of the conquest, conquistadors ruled their new possessions in the Americas from the island of Hispaniola (now divided into Haiti and the Dominican Republic). Within 150 years, they had killed off most of the original inhabitants through open warfare, disease, and starvation. Some scholars suggest that millions of native people may have died in the Caribbean during this period.

Regrettably little information remains about the culture of these indigenous groups. Some native foods like cassava (similar to the potato) are still cultivated; practices such as sleeping in hammocks and smoking tobacco also persist. The names of many Caribbean islands derive from indigenous languages (e.g., Cuba from “Cubanacan,” Taíno for “central place”). One type of communal music event is mentioned in early accounts as well, involving as many as a thousand participants who danced in circles around a group of musicians. Some of these ceremonieswere religious, others took place after the death of a community member or in preparation for war. They could last several days. Dancers would sing chants in a responsorial style, following a lead singer and accompanied by various percussion instruments. These included hollowed-out logs, maraca-like instruments, and gourd scrapers similar to the modern güiro. Small hand percussion of this sort may have persisted as an indigenous musical influence into the present.

From the late 1490s through the mid-seventeenth century, Spain alone controlled the Caribbean region; Caribbean countries that speak Spanish today thus reflect the earliest phase of European colonization. In the seventeenth century, Britain, France, and the Netherlands began to contest Spanish authority and to attack various islands. In 1650, the British succeeded in taking the island of Jamaica. France controlled much of Hispañola by 1664. Trinidad and Tobago passed hands at various times between the British, French, and Dutch.

The Atlantic slave trade greatly influenced modern Caribbean history and culture. The slave trade accelerated in the late seventeenth century as colonial powers established plantations to cultivate sugar and other crops. Following massive slave revolts in the French Caribbean of the 1790s, other islands including Cuba began importing slaves in larger numbers to meet the European demand for sugar. By the 1880s, when slavery was finally abolished in all of Latin America, three or four million Africans and African descendants lived in the Caribbean region.

African descendants in the Americas derive from three major West African cultural groups: (1) Muslim-influenced peoples originating in the Sudan, the Gambia, and Sierra Leone; (2) Bantu-Kongo tribes from the area that now comprises Angola, Central African Republic, and the Democratic Republic of Congo; and (3) groups associated with the coastal rainforest regions of present-day Cameroon, Nigeria, and Benin, especially the Yoruba. Bantu groups are prominent in all former Portuguese and Spanish colonies. Yoruba-derived traditions are strongly represented in countries such as Cuba whose slave trade peaked in the final decades before abolition.

Spanish-derived music has strongly influenced traditions throughout Latin America as well. Musicians accompanied the conquistadors on their very first visits to the Americas. Likewise, Catholic priests incorporated music into their efforts to “civilize” and convert first indigenous groups and later Africans. The legacy of Spain is evident in the many epic ballads and songs still sung in the region, as well as their poetic forms. European-derived instruments abound as well. Virtually all string and keyboard instruments in the region come from Spain or were based on European models. Even though they represented a demographic minority in the Caribbean, Europeans controlled local societies and influenced them profoundly. They brought elite musical traditions, i.e., classical music of various sorts and church music performed by conservatory-trained instrumentalists, as well as traditional music. This split reflects the divisions between the poorer, common people who emigrated from Europe and the smaller circle that controlled political and business interests.

Cuba is the largest and most populous island of the Caribbean, and lies less than 100 miles south of the Florida coast. Cristopher Columbus visited the island during his first voyage across the Atlantic; it remained a Spanish colony for over four hundred years. Following a series of Wars of Independence, Cuba became independent, though heavily influenced by the business interests and foreign policy of the United States. In 1959 the island entered a new period of revolution, left-leaning politics, and alignment with the Soviet Union. Since 1989, Cuba has struggled to survive without the assistance of its former Soviet allies and continues to be constrained by the U.S. economic embargo.

In depth

The proximity of Cuba to the United States has caused many tensions between the two countries. By the late nineteenth century, only two Spanish colonies remained in the Americas: Cuba and Puerto Rico. Many North Americans sympathized with the independence movement in Cuba, led by José Martí (1853-1895). The U.S. government, however, saw in the conflict a chance to annex the island from Spain; this eventually led to the Spanish-American War of 1898, after which both Cuba and Puerto Rico came under U.S. influence. Despite Cuba’s official independence in 1902, its economy and government remained in the grip of the U.S., which still retains a naval base at Guantánamo Bay. Puerto Rico became a U.S. commonwealth in 1917, a status it still retains.

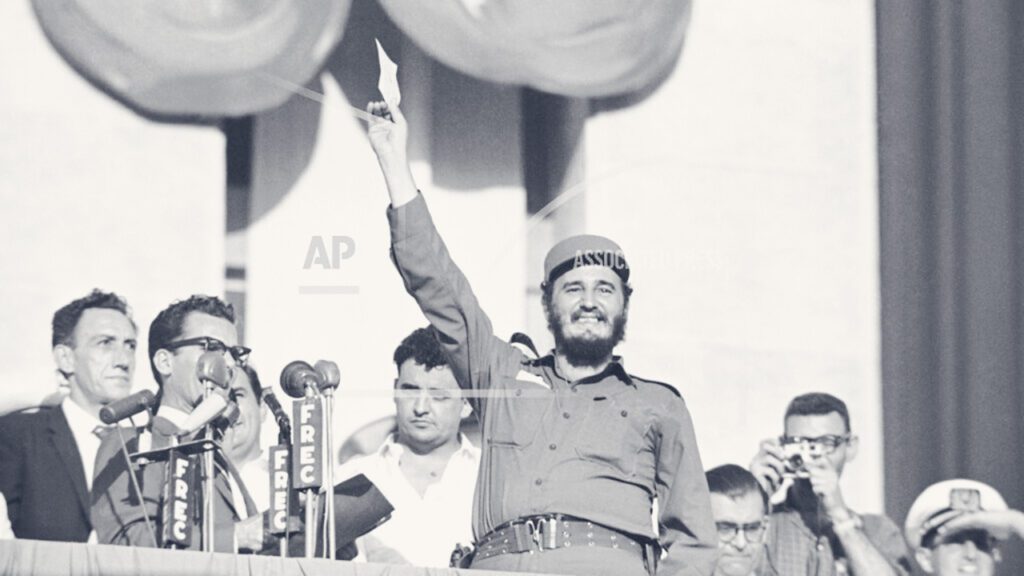

Fidel Castro (b. 1926) led a new revolutionary effort in the 1950s and wrested control from dictator Fulgencio Batista. Castro had communist sympathies and soon allied himself with the former Soviet Union, nationalizing or evicting foreign companies, and threatening to spread leftist revolution throughout Latin America. This alarmed the U.S. government and led to attempts to assassinate him, to overthrow his government (the Bay of Pigs Invasion), to a crisis over the stationing of Soviet nuclear weapons in Cuba in 1962, and the imposition of an economic embargo. The embargo has increased the hardships of the Cuban people without weakening the revolutionary leadership.

During the first half of the twentieth century, Cuba became a playground for vacationing Americans, and especially in the 1950s a center for gambling and organized crime. Since 1959, relations between the countries have entered a deep freeze, with severe restrictions on travel and no formal diplomatic relations. Cuban expatriates who fled the Castro revolution have congregated in Miami and elsewhere, where they exert a strong influence on North American politics, especially as regards maintaining the embargo. Politics within the exile community have been changing, however, and hopefully improved relations with Cuba will be possible in the coming years.

Música guajira is the term used in Cuba to denote traditional music associated with rural farmers, often of Spanish ancestry. Música guajira is most frequently heard on the western end of the island (known for its tobacco farms), and in the center, specifically the area stretching from Santa Clara to Camagüey. It is music for entertainment, performed at parties and other informal gatherings, as well as at annual competitions such as the Festival Cuculambé. Spanish-derived string instruments predominate in this repertoire and come in a bewildering number of shapes and sizes. One of the most common instruments used is the tres, an instrument like the guitar but smaller, and with three double sets of metal strings. Similar music exists Puerto Rico that foreground the cuatro, a folk guitar with four or five doubled strings. Spanish-derived string repertoire of a similar nature exists in Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, and throughout the hemisphere.

Cuban música guajirais usually performed in a major key and in triple meter. It emphasizes sung poetry, with instruments in a secondary or supportive role. In many cases, singers and instrumentalists use pre-composed melodies or chord progressions rather than creating new ones. Singers tend to improvise their lyrics on the spot, just as rappers in the United States might do.

Música guajira lyrics are expected to follow strict and difficult rhyme sequences. One common pattern, known as a quatrain,uses a four-line “internal” rhyme scheme in which line one rhymes with line four and line two with line three (ABBA). A more extended variant of the same idea consists of two five-line units; the first half adopts the structure ABBAA, a quatrain with an extra line; the second half follows the same pattern, but with different rhymes: CDDCC. In Latin America, the generic name for this sort of poetry with ten lines is décima poetry.

A recent example of décimasfrom Puerto Rico is provided on the CD Ecos de Borinquen: Jíbaro Hasta el Hueso, by Smithsonian Folkways. It exemplifies the way many Caribbean performers foreground local identity and images of rural life in such music. Another interesting aspect of virtually all compositions on the release is that they include a “forced foot” (pie forzado), a poetic line the singer is obliged to work into the last phrase of every décima. The pieces on the CD are pre-composed, but a forced foot may also be given to singers in competitions to see how effectively they can incorporate it as they improvise. The Smithsonian Folkways website provides video clips of the Ecos de Borinquen performances as well.

Listening example 5.1 presents improvised décima poetry from Cuba. It is called simply “Controversia” or “controversy,” the name for an improvised poetic duel. Note that the pulse of the song is not strict, but instead slows down and speeds up at various points. Musicians perform slowly and out of time in the background as singers improvise new verse. When singers finish a given segment, the musicians suddenly break into a lively tempo, playing repeated stock phrases in variation until one of the singers begins again.

In some cases, while one singer is in the process of inventing a verse, the other may actually jump in and “steal” the verse away with a different line than his/her opponent was planning, but one that nevertheless rhymes appropriately within the décima. This sort of intervention takes place in our listening example during the last minute or two of the track as indicated in the listening guide. A partial guide is provided below because the full transcription is rather long. The full guide is available on the textbook website . Bold letters outline the décima rhyme scheme.

The scope and diversity of Afro-Caribbean musical traditions is nearly overwhelming, and much research remains to be done on their countless variants. African musical heritage is strongest in religious repertoire. In many countries, African slaves and their descendants managed to reconstruct their ancestral beliefs, using religious worship to retain a sense of common heritage. Indeed, some colonial authorities encouraged the creation of Afro-Caribbean religious institutions; they hoped slaves would maintain both their distinct identities and the ethnic rivalries that some harbored, making them less likely to revolt en masse.

Listening example 5.2 comes from Cuban Yoruba-derived traditions associated with the religion known as “Santería” or Regla de Ocha; Santería means worship of saints or deities, but in this case African deities as well as Catholic ones. Traditional West African religion is based on ancestor veneration, including the spirits of deceased parents and other family members. Even the most powerful deities (orishas) of Santería are believed to be ancestors as well, figures who lived centuries ago but whose spirits still influence the present. They represent fundamental aspects of human life in a metaphorical sense: wisdom, motherhood, beauty, skill in warfare, and aspects of nature. Perhaps most important for our purposes, both music and dance are fundamental to worship of theorishas.

Each deity in this religion has many specific praise songs, rhythms, and dance movements dedicated to him/her. Santería involves spirit possession; practitioners believe that the gods want to advise those on earth and will take over the body of an initiate in specific contexts to interact with the community. Yoruba-influenced religious music in Cuba has multiple ensembles; here there is time to discuss only one representative example: batá drumming, considered the most sacred.

Batá drumming typically takes place in the homes of individual believers. Worship may be organized to celebrate a particular saint’s day, to become an initiate, to mark the anniversary of becoming an initiate, or for other reasons. The ensemble consists of a set of three hourglass-shaped, double-headed drums (batás). The largest drum leads the others, performs the most extended improvisations, and (together with the lead singer) provides cues to transition between rhythms. The middle drum also performs considerable improvisation and elaboration as it complements the rhythms of the lead drum. The smallest drum functions as a metronome, providing a basic pulse and playing a relatively static rhythms.

Sacred batásused in ritual contexts must be constructed and consecrated through an elaborate ritual process. They are believed to contain an orisha that aids in communication with other divine beings. Since the 1930s, unconsecrated drums have also been made for use in secular contexts. Recently such drums have appeared in jazz and popular music ensembles, as well as in more traditional contexts.

Each batá drum has a large head and a small head. The larger heads generate the prominent open and closed tones that, in combination with other drums, create characteristic aggregate melodies specific to each rhythm. The smaller head is more often slapped, providing rhythmic accompaniment. The large drum usually has a net of brass bells draped around the outside; the jingling creates a complementary sound to that of the drumheads. A lead singer and a chorus complete the performance ensemble. They sing praise songs in a fragmented, 200-year-old form of Yoruba as brought to the island by slaves in the nineteenth century; the exact meanings of some songs have been lost.

Formal religious events often begin with unaccompanied drumming in front of an altar hours before most guests arrive; this serves to purify the space. Drums play a series of rhythms dedicated to particular orishas in prescribed order that takes roughly half an hour. A second kind of drumming begins after most guests have arrived, providing accompaniment for dancers and singers during the main event. This is the kind of music that has been recreated in the recording studio by the performers of Listening Example 5.2 . The second section also begins by praising major orishas(there are about twenty of them) in prescribed order. Following this, the lead singer is at liberty to choose songs with greater freedom, and to invoke a particular orisha repeatedly as necessary to induce spirit possession. In all, ceremonies last many hours.

Our example of batámusic comes from the CD Tambor Yoruba: Elegguá, Oggún, y Ochosi. “Tambor” is the word for “drum” in Spanish, and the final three words in the CD’s title refer to particular orishas, all of them warriors. Elegguá is known as a messenger, “guardian of the crossroads” or important moments involving choice, and also as an opener of doorways, spiritual and otherwise. He is always worshipped first in any event to facilitate communication with the other divinities. Oggún is an orisha of the forge and metal working, known for his dogged determination. Ochosi is a wise woodsman and hunter whose symbol is the bow and arrow. All major orishas in the Santería religion are associated with particular Catholic saints as well. In this hybrid form of devotion, for instance, Ochosi is believed to be an incarnation of the Catholic angel Santiago and of an African deity simultaneously.

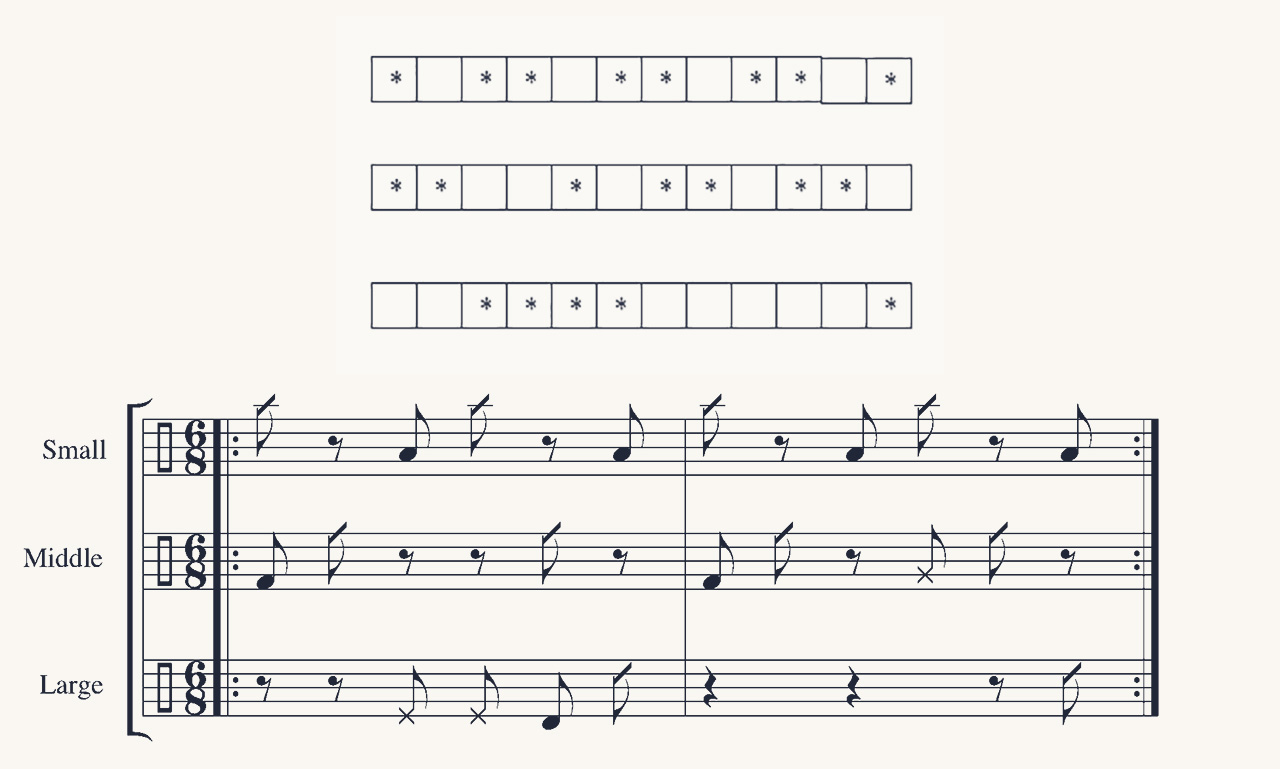

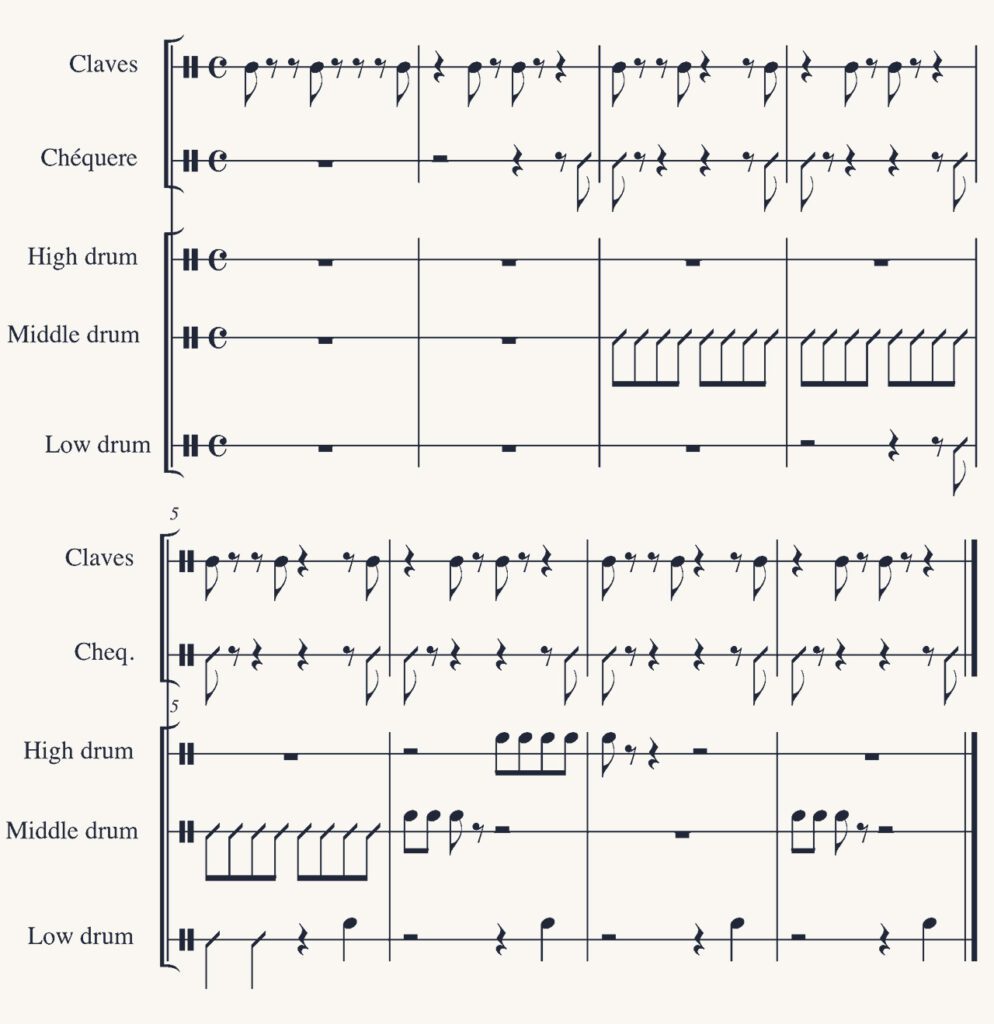

The rhythms associated with batádrumming are complex, and with six heads sounding at once it takes time to learn to distinguish between all of them. Below is a transcription of one rhythm heard in this excerpt, called ñongo; it is one of about thirty standard batárhythms used to accompany religious ceremony, and is heard in our example beginning at 1:10”. In the Western notation, high notes represents hits on the small drumhead and low notes on the large head. Slash heads indicate slaps, an “x” means a muffled tone, and a normal round notehead indicates an open tone.

Try to reproduce the rhythmic patterns above, then try to sing a couple of the melodies in this piece. You can learn them by ear, like performers in the Caribbean do. Or if you read music, refer to the transcription of the melodies (Ex. 5.2). Note that in cases where the melody is divided, smaller text indicates the part sung by the lead singer and capital letters indicate the response by the chorus. Remember that the lead singer improvises and changes his melody constantly, so the transcription represents only one way he might sing it.

To contrast this piece with a different African-influenced tradition from Cuba, consider the rumba. Rumba music is secular, not religious; it developed in the late nineteenth century out of earlier forms associated with Cuba’s rural Afro-Cuban population. With the abolition of slavery in 1886, many former slaves and agricultural workers moved to cities such as Havana and Matanzas in search of better jobs and an education. In these cities, in large tenement buildings, rumba music and dance coalesced as a style. Like música guajira, it is a form of entertainment, traditionally performed among friends or community members. Many variants exist; Bantu/Kongo rhythms and culture are said to have been especially influential in rumba’s formation, and in fact the “conga” drum (also known as a tumbadora) still bears the name of this ethnic group.

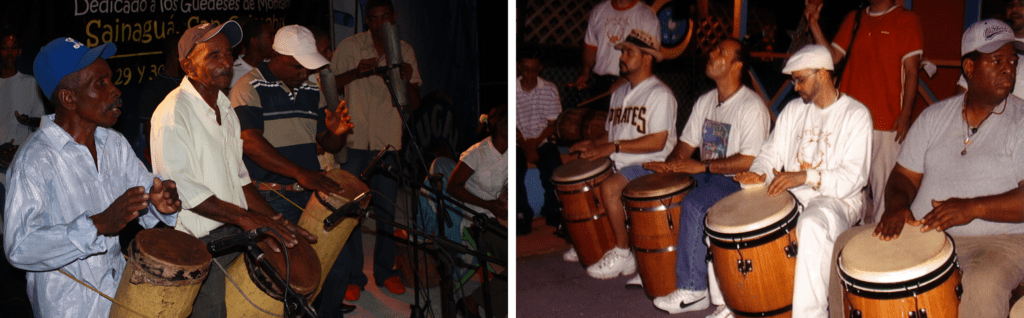

Rumba can still be heard on the street corners of poorer neighborhoods and similar informal contexts (see Fig. 5.6). Because of its close associations with the Black working class, and widespread bias against drumming on the part of elites, laws existed to keep it from being performed in other areas for many years. Even today, some Cubans cannot see value in this music, or in African-derived religious repertoire, considering it backward or uninteresting. Nevertheless, rumba has been recognized as a bona fide part of Cuban culture; since the 1970s, the ministry of culture has supported it through recordings and promotion, and finds places for rumba musicians to perform publicly on a regular basis. These include “Sábado de la Rumba” (Rumba Saturday) events hosted by the state-supported National Folklore Troupe (the Conjunto Folklórico Nacional).

Many instruments can be used to perform rumba, but the most common are a set of three conga drums of different sizes, a set of claves (short, resonant wooden sticks), and a pair of sticks used to strike a wood block or the side of a drum itself. The rhythm produced by the sticks is sometimes called a “shell pattern” (cáscara) because it was often performed on the shell of a drum. This pattern has been adopted by present-day salsa performers, as discussed later. Sometimes resonant boxes (see Fig. 5.6) are heard as well, or other percussion. As in the case of batá drumming, a lead singer and chorus perform along with drummers and dancers. The drum with the highest pitch improvises most in this style. The middle-pitched drum and the lowest-pitched play more static patterns, though they can also improvise. By contrast, the claves and sticks play patterns that remain constant throughout the performance.

Rumba sounds African-derived to many listeners, but upon closer examination it also demonstrates European influences. Most songs are sung in Spanish, for instance. The first section of the music is strophic, with changing lyrics over a constant melody, a European concept. Some of the poetic forms employed are also Spanish-derived, including the décima described earlier. Rumba lyrics touch on many topics including love, politics, famous rumba players of the past, and the like. As in the case of most traditional music, rumba tends to be performed in a single key and does not modulate.

Rumbas typically begin with a brief improvised melody over the percussion rhythms, sung by the lead singer in order to establish a tonal center. After this come the two major sections of the piece: the strophic verse, then a final section, the fastest and most improvisatory known as the montuno. In the montuno, the lead singer improvises short vocal lines in alternation with the chorus, much like in the batáexample above. The tempo speeds up a bit, dancers begin to dance, and the lead conga player improvises more aggressively. This spontaneous jam can last as long as the participants feel inspired to continue, anywhere from a few minutes to half an hour or longer. The montuno is cyclic, based on repeating loops of rhythms and interlocking sounds; this sort of open-ended performance style derives from traditional West African aesthetics.

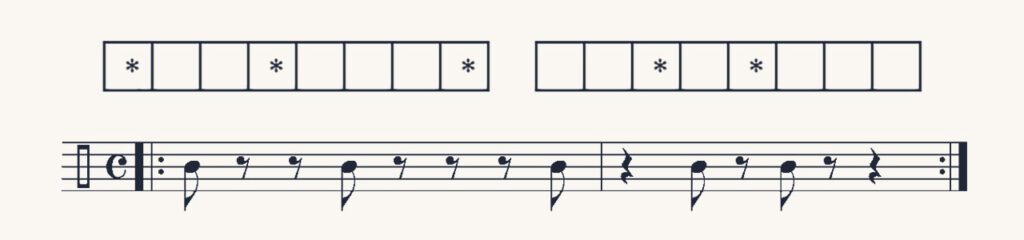

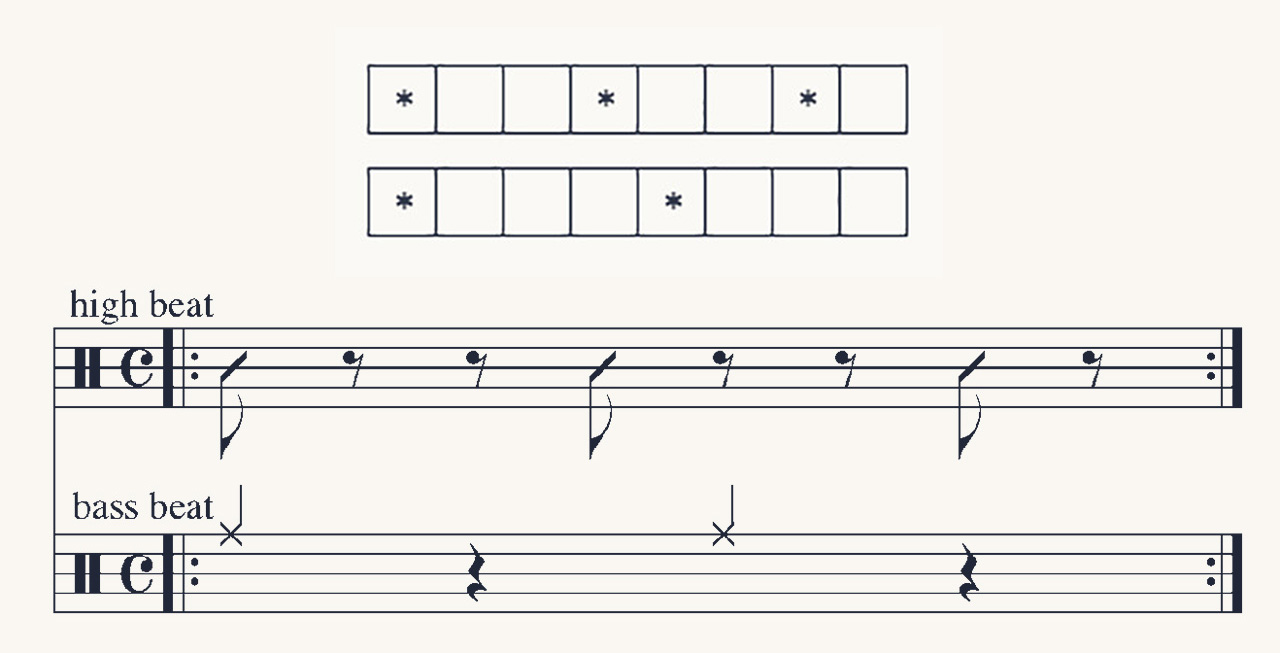

Before continuing, it is important to discuss clave. “Clave” or “claves” can refer to a percussion instrument, as mentioned. However, clave also refers to a constantly repeated rhythmic figure that serves as the structural foundation for the rest of a piece’s rhythms. Repeated patterns of this sort are found in many kinds of Afro-Caribbean music. They often contrast a more syncopated figure in one half of the clave rhythm (often known as the “three-side,” since it incorporates three beats) against a relatively straight figure in the other half (known as the “two-side”). As mentioned, the clave patternshould correspond with other rhythms in the song; if such a correspondence does not occur, musicians may describe the song as being “out of clave” or having a “crossed clave.” Distinct clave patterns exist for the son, rumba, Yoruba-derived religious music, and other genres.

Listening example 5.3 provides a good introduction to Cuban rumba and to the notion of clave because it is fairly slow and the drum parts are relatively easy to hear. This piece is actually a remake of a song originally written for guitar and voice in the early twentieth century. The only unusual aspect of it musically is that it does not include a stick part. Try listening to the beginning of the track. It starts with a pair of clavesplaying the traditional rumba clave:

Next, a chekeré, a gourd shaker with a net of beads around it, enters at about 0:03” playing “and-one” at the end of each measure and the beginning of the next. The middle conga drum enters simultaneously. Initially it plays soft, muted notes with rapid touches on the drum head. After this, it plays prominent open tones against the “two side” of the clave. Sometimes the middle drum plays several open tones in a row, sometimes a single tone. This first happens at about 0:07” and 0:09”.

Against all this, the low drum enters as well, improvising for a moment about 0:05” and then playing a clear open tone on beat “4” of each measure (you can hear it at about 0:07” and 0:09”, for instance). Finally, the high lead drum makes its first entrance at about 0:08” with a series of prominent open tones. Try listening to the drum patterns on headphones for clarity, focusing on their different pitches in order to distinguish them. A complete transcription of the percussion parts against one another during the first ten or so seconds of the song would look something like this in Western notation:

As you listen through this piece, you will begin to hear the characteristic melody in this subgenre of rumba, a melody created through the interaction of the open tones on the two lower conga drums. That constant low-high pitch alternation, with the open tones of the middle drum against the “two side” of the clave, forms the essence of the sound. Try to keep track of the clave as the piece plays, as well as of the low drum and chekerépatterns, which are relatively constant. Then focus on the improvisations by the high conga drum, noticing how they become busier between vocals and at the end of the song. Listen for the beginning of the montuno and the increase in tempo that ensues.

Traditional rumba has influenced many composers and musical styles. The two-part form of the rumba with its verse and montuno has served as the model for contemporary salsa. The shell rhythms played by the sticks have been adopted by the timbales, also in modern dance music. And rumba rhythms are now used in various formats, from Latin jazz to classical chamber music to pop songs. If you can find the recordings, listen to pieces such as “Obsesión” (interpreted by Manny Oquendo and Libre) or “Camerata en guaguancó” (interpreted by the Camerata Romeu) and see if you can hear how they have been influenced by traditional rumba.

The most widely known form of Cuban popular music is the son (not to be confused with other sonesfrom countries such as Mexico). Son has become a national symbol, in large part because it effectively integrates African and European aesthetics. Although its lyrics are primarily in Spanish, African-derived terminology also appears at times. Son instrumentation includes both string instruments from Spain and percussion modeled on African traditions. It incorporates European harmonies but combines them with ostinati —looped, repeated rhythmic or melodic patterns — in an African style. As in the case of the rumba, the structure of son music is hybrid, combining a strophic verse section and a call-response montuno, similarly demonstrating the fusion of African and European influences. Finally, the dance style is also mestizo, with a choreography derived from European-style couple dancing, but adding hip and shoulder movements derived from West Africa.

Cuban son developed around 1890 in eastern Cuba where it was performed by Afro-Cubans in the hills surrounding cities such as Santiago, primarily at parties and similar gatherings. In its earliest manifestations, the son consisted of only a repeated choral refrain supported by percussion and very simple tonic-dominant chords on a string instrument (usually the tres). Against this, a lead singer might improvise brief phrases, in alternation with the chorus.

The years following the Wars of Independence against Spain witnessed much demographic movement on the island. Eventually, performers brought the rural son to Havana where it began to fuse with the bolero (see below) and other popular music traditions, including North American jazz. By the 1920s an urban son stylehad developed and was first performed publicly in beer gardens, dance academies, brothels, and other sites of working-class entertainment (similar in this respect to early jazz, the tango, etc.). Its typical instrumentation included guitar, the smaller, guitar-like tres, maracas, claves, bongo drum, bass, and later a trumpet. Sones broke many racial barriers as it gained widespread acceptance, allowing working-class performers of color into the mainstream music industry for the first time.

Various musical characteristics define the son. One is its clave rhythm, usually played on the clavesthemselves. Another are the unique melodies played on the tres, outlining or implying chords but not actually strumming them. In the final montuno, especially, melodies on lead string instrumentsoften correspond to the clave, with a syncopated half of the melody played against the “three-side” and a straighter rhythm played against the “two side.” Another pattern found in son music, played by the bongo drum (see Fig. 5.7), consists of strong strokes on the smaller head of the drum on beats one and three of a 4/4 measure, and then a hit on four on the larger drumhead. However, bongo players improvise frequently, deviating from this pattern.

Probably the most unique aspect of the son is its anticipated bass; bass notes are often played slightly earlier than one might expect. In many types of music the bass pattern sounds on “one” and “three” of the 4/4 measure, as for instance in rock or U.S. country music. In the son, by contrast, the bass plays on the and-of-two (i.e., an eighth note before the “normal” spot on beat three) and on four (a full quarter note before the “normal” spot on beat one). This lends the music a syncopated feel and can make it hard to discern the downbeat.

Below is a guide to Listening Example 5.4 , an example of traditional son as interpreted by a modern-day ensemble. The small quartet performing here includes only bass, a guitar that has been modified with doubled strings to sound like a tres, bongo, maracas, and voices. Yet musical elements are easy to hear in the smaller group, and the overall sound is like that of early son bands. The only unusual aspect of the piece is that some verses repeat after the chorus is heard; usually a longer montunowould follow the verses and end the song.

In the 1940s, an expanded son music format that included a second and often a third trumpet became popular in Cuba. This in turn required written arrangements to coordinate melodies played by the entire wind section. As more performers joined son bands and music literacy spread, groups performed more structurally and harmonically elaborate pieces. Pianos became a standard part of son instrumentation at this time. A single conga drum was added as well, and by the 1950s the timbales came to be played alongside the bongo and two congas. This expanded format contributed to the development of salsa music in the 1960s and 1970s as performed by Latin American immigrants in New York. Salsa musicians adapted the son style to their own needs and tastes, in some cases changing the original style markedly.

In this piece, the musicians imitate a Puerto Rican rhythm called bomba sicá from 1:12-1:28”. Research this rhythm on your own, and about bomba music in general, on your own to determine how it has influenced salsa.

In New York, salsa first gained popularity in the context of social and political activism on the part of Latino immigrants. Many lived in the poorer neighborhoods of east Harlem and the Bronx. As they struggled to get by in their new home, they came to resent the disregard for Latin American history and the Spanish language within most public schools. Salsa thus became an important emblem of cultural identity as Latinos slowly asserted their rights. Many also associated the music with the movement in Puerto Rico for complete independence from the United States.

Partly for these reasons, early New York salsa has a raw, edgy sound. It tends to be performed at a much faster tempo than son, with percussion featured prominently. Its harmonies are more complex than that of earlier Cuban dance genres, reflecting the influence of jazz and other U.S. repertoire. The prominent use of trombones also makes the sound distinct. New York-based salsa performers may incorporate folk instruments such as the cuatro, or percussion rhythms unique to Puerto Rico or elsewhere in Latin America as well.

Two well known performers who lived in New York for many years collaborated on Listening Example 5.5: Celia Cruz and Ray Barretto. Celia Cruz (1925-2003) represents one of the best known vocalists during salsa’s heyday in the 1970s and 1980s. Born in Havana, Cuba to a modest family, Cruz first came to the attention of the public singing on local radio broadcasts in the 1940s. After she won several talent competitions, a dance band called La Sonora Matancera (The Matanzas Sound) offered her a job as a singer. Following the Cuban revolution of 1959, Cruz and other Sonora Matancera band members left the island and resettled in the United States. She recorded subsequently with bandleaders such as Puerto Rican Tito Puente and Dominican Johnny Pacheco, becoming a star on New York’s Fania Record label. Her death was a major public event in Miami, with hundreds of thousands of fans taking to the streets in remembrance.

If you like salsa, compare the sound of this example to timba from Cuba that mixes son and salsa with funk, rap, and Afro-Cuban traditional music. Groups such as Azúcar Negra, La Charanga Habanera, and Klímax are examples of timbabands.

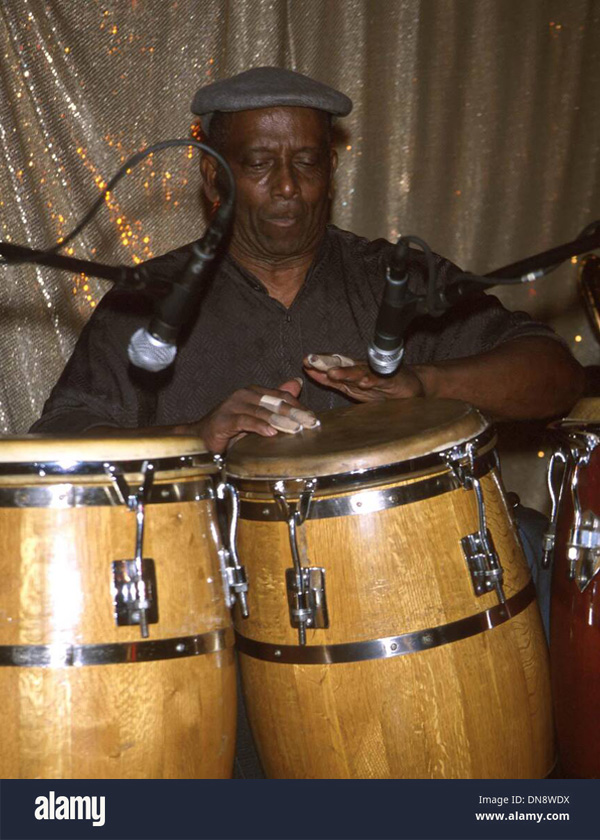

Conga player and bandleader Ray Barretto (1929-2006) is remembered as an award-winning musician and a prominent part of the U.S. salsa and Latin jazz scenes for many years. Born in New York to parents of Puerto Rican descent, Barretto grew up listening to mainstream music from the U.S., jazz, and traditional music of the Spanish-speaking Caribbean. In the early 1960s his music fused elements of Latin dance music with R&B and he played conga on recordings for groups such as the Rolling Stones. In 1967 he too joined the Fania label, eventually becoming its musical director. In 1990 Barretto was awarded a Grammy for his Ritmo en el corazón CD, which features our listening example.

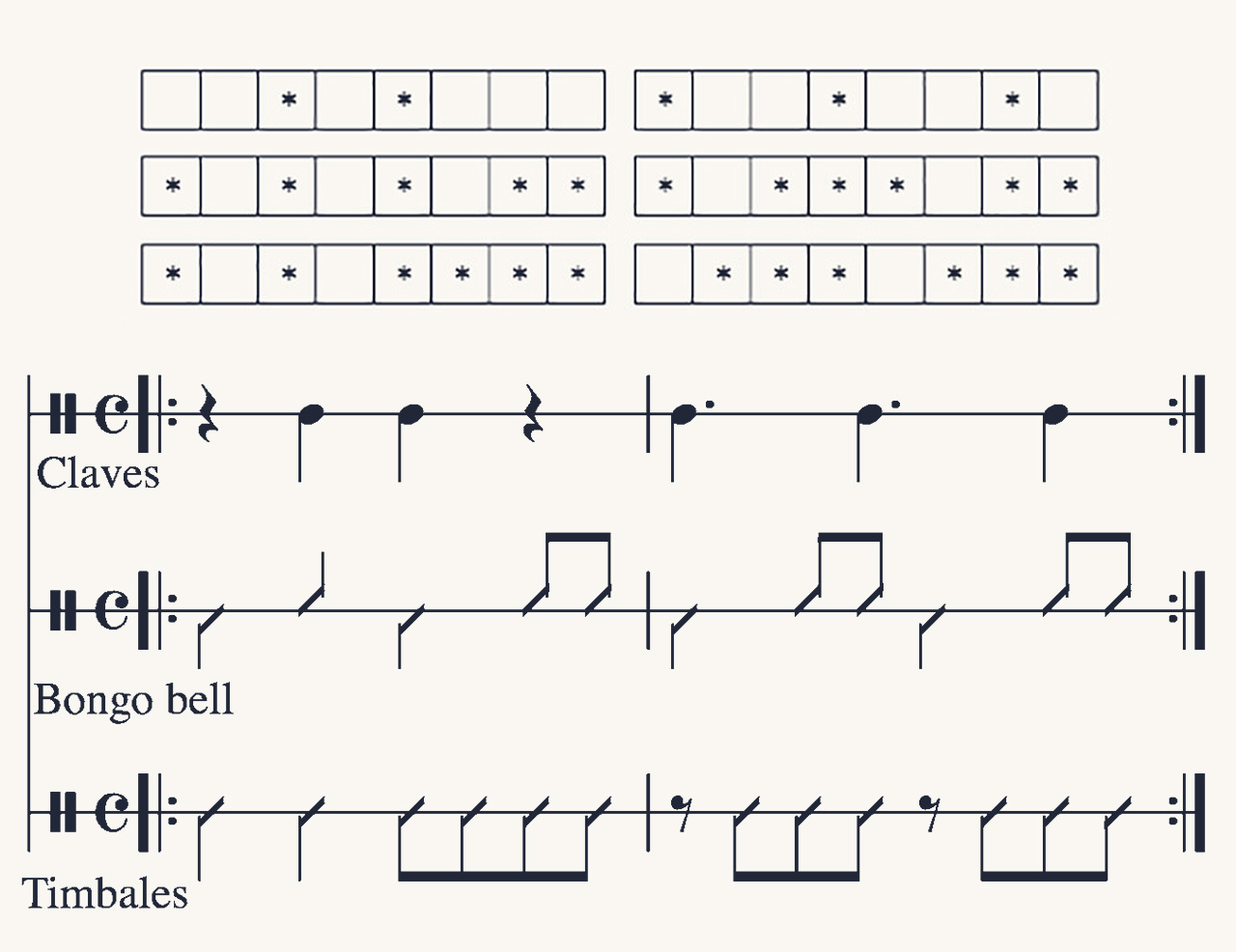

Many other musical aspects of salsa could be discussed, but one of the most prominent is its bell patterns. The timbales sticks play on the side of the drum during the verse, but switch to a driving bell pattern that locks together with the bongo bell during the montuno. Here is a transcription of typical bell patterns played by the timbales and bongo players against son clave. In the staff transcription, stems down on the bongo bell indicate a stroke on the larger end; stems up indicate a stroke on the smaller end.

Merengue has long been the most popular music in the Dominican Republic. It began as an Afro-Dominican variant of ballroom genres imported from Europe such as the polka. Initially rejected by elite Dominicans as vulgar — because of its intimate dancing, its associations with the working classes, and its instrumentation which includes African-derived percussion — merengue slowly gained acceptance in the 1920s and 1930s. The instrumentation of the traditional rural merengueconsists of button accordion, metal scraper (güira), a bass instrument of some sort (sometimes a large African-derived thumb piano), a double-headed drum called the tambora, and singers. Over the years, commercial merengue has adopted influences from jazz and international popular music, as in the case of son and salsa. Pianos now perform many commercial merengues instead of the accordion, and often a large horn section features saxophones and trumpets. Merengue became an international phenomenon in the 1980s, competing with salsa for air play on Latin radio stations throughout much of Latin America and the U.S.

Most merengues have a form like that of salsa: they begin with an instrumental introduction followed by a verse and finally a call-response section, interspersed with horn interludes. Horn lines in later sections often overlap each other just like the moñas of salsa music, fitting together in a manner similar to the percussion parts. The technique derives from West African musical structures (refer to the earlier commentary on batás and rumba).

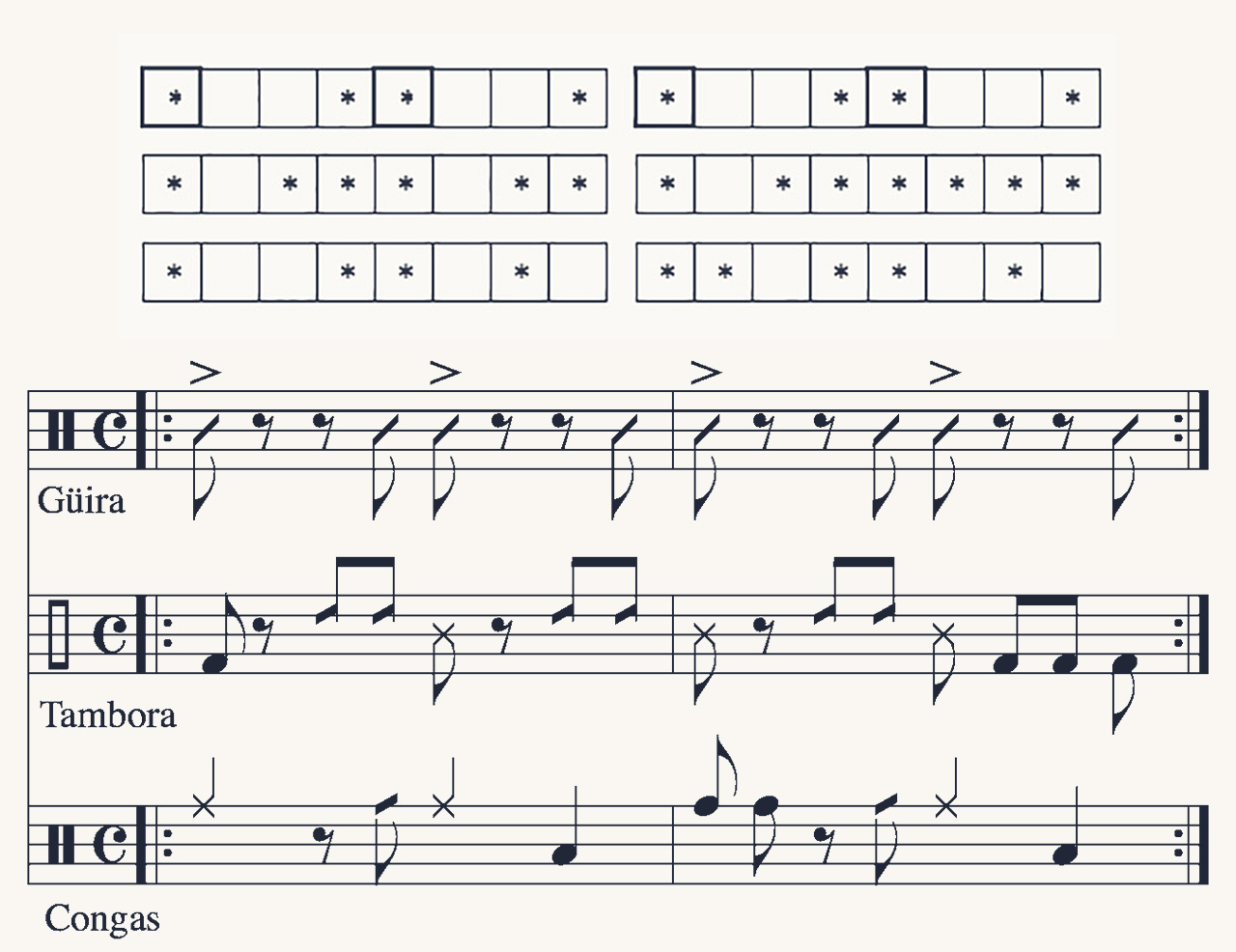

The tambora has its own unique rhythms to play. Percussionists place the drum across their knees and strike one head with a stick, the other with their hand. The hand with the stick sounds more loudly, alternating high, sharp cracks on the rim of the drum and open tones on the head. The metal scrapertends to emphasize strong beats (“one” and “three” of the 4/4 measure), but also improvises with virtuosic flourishes and variations. In larger dance bands, conga drums play a characteristic two-measure pattern against other percussion.

A transcription of characteristic rhythms performed by these percussion instruments appears below. In the tambora line of the staff notation, round note heads designate an open tone and slash heads a rim shot. In both the tambora and conga lines, stems up are performed by the strong hand, stems down with the weak hand, and an “x” designates a slap. In the conga transcription, the different levels denote drums tuned at different pitches; slash heads indicate a soft touch. Blackened boxes in the TUBS graph represent stronger accented notes

As you play Listening Example 5.6 , you will recognize that one unique quality of this genre is its speed: merengue tempos and horn lines are usually more rapid than in other Latin dance music. The prominence of saxophone is also striking. Saxophones play fast, repeated melodies, outlining the chords. Keyboard parts in modern merengue also tend to be fast and syncopated, like those in salsa. Bass part vary. In the past, the most common beat was a straightforward pulse on “one” and “three.” However, in the last fifteen years a drum set’s floor tom has taken over this role, and the bass has been used more to add color or “punch” at various moments. Sliding and slapping sounds are prominent, and bassists stop and start rather than playing consistently. Note that complete lyrics to the example below should be available on the internet.

The term “bolero” is used in Spain to refer to a genre of music played in triple meter to the accompaniment of string instruments and castanets, but the Latin American bolero is an urban romantic song form influenced by European parlor music. It first developed in eastern Cuba in the late nineteenth century. Performers there, relatively affluent Afro-Cubans, used the term to describe songs in a slow duple meter, usually performed by two singers and accompanied by two guitars and claves. One guitar played a bass line and provided basic harmonic accompaniment, the other improvised melodies between vocal phrases. These Cuban boleros were slow and harmonically complex, intended for listening, with refined lyrics reflecting middle-class taste. Musicians played them in private homes, in cafes, and similar venues for their friends.

As an introduction to the bolero, try listening to “Dos gardenias” (Two Gardenias) or “Veinte años” (Twenty Years) from the Buena Vista Social Club releases of the mid-1990s, or Puerto Rican favorites such as “Perdón” (Forgive Me) or “Obsesión” (Obsession) by Pedro Flores.

Beginning in the 1930s, the genre spread internationally and Mexico became the most important center of bolero performance. Composers in that country (María Grever, Augustín Lara, etc.) fused the Cuban idiom with influences from jazz and popular music of the day. The popularity of recordings made in Mexico and disseminated through record sales, radio, and film resulted in the proliferation of new bolero composers and performers throughout Latin America. The mid-twentieth century represents a heyday of sorts for the boleroin which it dominated popular music recording throughout the region. A sampling of thousands of well known boleroshave been collected in Jaime Rico Salazar’s Cien años de boleros (Bogotá: Panamericana Press, 2000).

Since the 1950s, the bolero has continued to change. In the 1940 and 50s, bolero music accompanied by big-band orchestras became popular. Perhaps most the influential innovation as of the 1960s was the fusion of elements from the earlier classic bolero with elements of international pop music (the drum set, synthesizer, electric guitar, string arrangements, etc.). Mexican Armando Manzanero and Brazilian Roberto Carlos were early exponents of this variant. Some critics consider their songs “watered-down” Latin American culture, not “Latin” enough, yet they have proven very successful commercially. In the 1990s the bolero (with a somewhat “rockified” backtrack) made a strong come back across Latin America with the wildly successful recordings of Mexican Luis Miguel.

In depth

In the Dominican Republic, bolero repertoire from Mexico and elsewhere inspired the music now referred to as bachata. The history of this bolerovariant demonstrates the ways in which international music traditions often become “localized” over time. As documented by Deborah Pacini Hernandez,bachataemerged in shanty towns on the edges of Santo Domingo in the 1970s. Early artists performed for dances and parties on acoustic guitars with small ensembles featuring the bass, bongo, and maracas, or metal scraper. At that time, the term “bachata” was used to refer to all music performed by the urban poor, including boleros and acoustic merengues.

Since the mid-1980s, however, bachata has come to represent a distinct genre, developed in part by musician Blas Durán. Modern bachata is performed at a slightly faster tempo than standard boleros and adopts a more percussive sound, although its harmonies tend to be simpler. Bands now feature electric guitars and additional percussion including drum set and drum machine. An electric guitar with a flange effects box typically plays instrumental melodies, often outlining chords in quick runs. A unique dance step has developed as well that involves taking three steps to each side in alternation followed by a distinctive hop-like motion. It is performed by couples who hold each other in a tight embrace, swinging their hips markedly.

Bachatalyricsfor many years employed colloquial forms of expression, “street slang,” rather than the refined lyrics of earlier boleros, and reflected a decidedly male perspective on love and relationships. Bachatalyrics often express despair, suffering, indignation, longing. Bawdiness and sexual double entendre are common as well. As one might imagine, therepertoire initially struck middle-class listeners as rather crude. Of course, since the music has gained a broader public its lyrical content has conformed more to that of other international popular music. The Bronx-based Dominican group Aventura represent one of the most successful recent groups, performing at the White House in 2009 and modernizing the image of the genre. Consult the internet and library resources to learn more about bachata’s history, the sound of the music, and its dance style.

Socially engaged song first became popular within Latin America in the 1960s and 70s; the most common term for it is “nueva canción” or “new song.” The genre first emerged in South America, specifically Argentina and the southern cone region (see Chapter 7), but it soon spread to the Caribbean and developed a loyal following there. Early enthusiasts tended to be young adults, primarily college-educated, and performed in coffee houses, on campuses, small theaters, and sometimes at political rallies. They sought an alternative to music dominating the media that they perceived as overly commercial. Some nueva canciónartists created new kinds of music of high quality, often by incorporating elements of local repertoire that earlier generations considered of little interest. Others co-opted international genres (rock, blues, the bolero) and adapted them to their own purposes. Nueva canciónlyrics have touched on many subjects, drawing attention to social injustice or discussing more conventional themes such as romance in fresh, unconventional ways.

Cuban youths who grew up in the aftermath of the revolution (1959) have been strong advocates of nueva canción (though Cubans refer to it as “nueva trova”). The government there actively encourages artists to comment on social issues and to avoid slavish imitation of music from the United States and Europe. Among prominent first-generation figures associated with the nueva canción movement are Pablo Milanés (b. 1943) and Silvio Rodríguez (b. 1946). Milanés, an Afro-Cuban, has consistently demonstrated an interest in traditional genres (son, bolero, rumba), and many of his songs demonstrate such influences. For his part, Silvio Rodríguez has more typically taken inspiration from international rockers including Bob Dylan and the Beatles. His musical output is extensive and quite varied; many songs are noteworthy for their harmonic complexity. Rodríguez’s lyrics are highly sophisticated and metaphorical. He was the first nueva canción musician recognized as such, appearing on Cuban television in 1968, and continues to be a prominent composer today.

Search for recorded examples of the Puerto Rican protest singers mentioned, and for further information on the plena. The short film Plena Is Work, Plena is Song (New York: Cinema Guild, 1989) provides a good introduction to the latter and its associations with protest; the book Music in the Hispanic Caribbean (Oxford University Press, 2010) contains info on both.

Listening Example 5.7 represents a good introduction to Rodríguez’s repertoire. The composition can be read as a love song, as commentary on the country’s political leadership, or as a critique of Cuba itself in the 1970s. Regarding the latter, the song’s at-times apocalyptic statements apparently refer to momentous events that framed the revolution’s initial decades such as the October missile crisis, the Cold War, the ongoing embargo and isolation of Cuba, and tense international relations. Though he is a believer is socialism, Rodríguez had numerous conflicts with government officials early in his career; perhaps for this reason, he has tended not to comment on the specific inspiration for many of his songs. The multiple readings of music increase its appeal to diverse audiences.

Puerto Rico has many of its own nueva canciónsingers including Roy Brown (b. 1945), Andrés Jiménez

(b. 1947), and Antonio Cabán Vale (b. 1942). Some compose in a style similar to that of Silvio Rodríguez; others work with local Puerto Rican traditional genres. Their music is worth exploring on your own, as it references important political tensions between Puerto Rico and the United States. And the plena, an important musical genre from the Afro-Puerto Rican community, has for many years served as a grassroots form of protest in its own right.

Reggaeton is one of the most popular forms of music from the Hispanic Caribbean, especially among younger listeners. The genre emerged in the early 1990s. It is fundamentally transnational, with roots in the modern dance music of Jamaica as well as in black U.S. genres. Characterized by segments of spoken and/or sung lead vocals and a constant, syncopated beat, reggaeton might be thought of as a form of Spanish-language rap that uses a rhythm known as “Dem Bow” under most tracks. Lyrics tend to focus on partying and romance, but some also reference issues of pan-Latin American and pan-Latino pride, racial consciousness, and other social concerns.

Aside from the music, fans also are also attracted to reggaeton dance moves, often of a provocative and sexually explicit nature. Probably the best known of these is “el perreo” (roughly, “doggy-style”), which seems to derive from Jamaican dances of the 1980s. The overt sexuality of many moves and the vulgarity of some reggaetonlyrics became the focus of considerable controversy for a time among those who preferred salsa, merengue, or other more traditional forms of music and dance.

The modern reggaetonbeat is created through the combination of a low drum playing a steady pulse on “1” and “3” of the 4/4 measure and a tresillo rhythm played against it by a contrasting instrument. The tresillo figure is found in virtually all of the Caribbean, as well as in other parts of Latin America influenced by African heritage. It is centuries old, with roots in the music of Kongo cultures and those of the Middle East.

Jamaican artist Shabba Ranks first popularized the reggaeton beat as modern dance music in his song “Dem Bow” from the 1991 CD Just Reality. “Dem Bow” circulated in several countries and influenced releases by numerous Spanish-speaking artists. By the mid-1990s, Puerto Rican producers had created entire albums based on the Dem Bow groove, re-labeling it reggaeton. The music can take many forms depending on who records it. While it foregrounds the samebeat, it may include introductions or interludes of entirely different rhythms. Artists often change the timbre of the instruments playing the tresillo and may add in new harmonies, background melodic figures, and so on. Current stars of the genre include Puerto Ricans Don Omar (William Omar Landrón, b. 1978) and Daddy Yankee (Ramón Ayala, b. 1977).

Listening Example 5.8 comes from Tego Calderón (b. 1971), an Afro-Puerto Rican performer. His music often incorporates insightful social commentary, and in some instances blends Puerto Rican traditional rhythms with electronic sounds. Calderón took the name for this composition from a small beachside neighborhood outside of San Juan known for its Afro-Puerto Rican population and its preservation of bomba drumming. The transcription below is partial; complete lyrics are available at www.***.

Cuba and the Caribbean have a long history of classical music performance, with the earliest forms of such repertoire associated with the Catholic church. As early as 1540, organists at the cathedral in Santo Domingo offered instruction to aspiring performers; by 1600, other cathedrals had been built and the post of chapel master was established, one that involved the coordination of all musical activity. As mentioned, colonial authorities used church music to convert indigenous and African peoples to Catholicism. For this reason, mixed-raceand non-European members of society figured prominently in the performance of European religious music from the earliest years. In Cuba, for instance, the mulatto Esteban Salas began composing in the 1750s; his substantial body of Baroque compositions consist of masses, psalm settings, motets, and Christmas music for church choir.

Secular forms of classical music took longer to develop. Their earliest manifestations, dating from the eighteenth century, involved music accompanying events of state such as the celebration of a new Spanish king or the performance of minuets and other light classical dance forms. Public concerts of classical music began to appear consistently only in the nineteenth century, owing to the growing wealth of colonial populations, primarily the result of profits from slave labor. A one-peso tax on the importation of each new slave brought to Cuba, for instance, provided Spanish governor Miguel Tacón with ample funding to create the Teatro Tacón in 1838, the largest opera and symphony house in North America or Latin America at the time. This and other theaters hosted artists from France, Spain, Italy, the United States, and elsewhere.

By the mid-nineteenth century, Cuban composers such as Laureano Fuentes Matons (1825-1898) began composing symphonies, operas, and chamber music in a European classical style. Nicolás Ruiz Espadero (1832-1890) established himself as one of Cuba’s first piano virtuosos, writing pieces modeled after those of Franz Liszt. Ignacio Cervantes (1847-1905), probably the most important Cuban composer of his era, wrote short, stylized dance music pieces for piano that was considered the epitome of Cuban national expression. In this sense he perfected a tradition established by his predecessor, Manuel Saumell (1817-70). In Puerto Rico, Felipe Gutiérrez Espinosa (1825-99) began composing operas and religious music beginning in the 1850s, and Manuel Gregorio Tavárez (1843-83) and Juan Morel Campos (1857-1896) salon repertoire based on dance music. Music conservatories were established in the Dominican Republic following its independence from Haiti in 1844, training composers such as José Reyes (1835–1905) and José María Arredondo (1840–1924).

In the final decades of the nineteenth century, the habanera song genre became popular internationally. The habanera rhythm on which it is based, virtually the same one heard in modern reggaeton, soon found its way into light classical compositions. Visitors to Cuba learned popular habaneras and performed them in other Latin American countries and in Europe. The rhythm contributed to the emergence of the Argentine tango and was featured in European operas of the day such as Bizet’s Carmen (1875). Other European classical composers who have used the habanera rhythm in their works include Debussy, Ravel, Albéniz, and de Falla.

Composer and violinist Amadeo Roldán (1900-39) became director of Havana’s municipal conservatory in the 1920s, as well as director of the Philharmonic Orchestra, one of two symphonies in that city. In 1930, Roldán, a bold experimenter and modernist, wrote the first piece of classical music exclusively for percussion as part of a work called Rítmicas. He and his contemporary Alejandro García Caturla (1906-40) promoted an artistic movement called afrocubanismo, attempting to reconcile influences from Afro-Cuban percussion and/or song with classical traditions. Movements 5 and 6 of Rítmicas, for instance, feature claves, bongo, güiro, and other traditional instruments. This work generated considerable controversy among conservative listeners of the day who did not feel that such instruments were appropriate in the concert hall.

One of the most famous and commercially successful Caribbean classical composers of all time is Ernesto Lecuona (1896-1963). His career reflects Cuba’s strong tradition of classical piano performance. In the 1950s, Lecuona’s name was well known even to many North Americans. He grew up in a fairly affluent family outside of Havana and developed a reputation as a child prodigy; most who heard him believed that he was destined for a career as a concert soloist. After the premature death of his father, however, Lecuona began playing music in theaters to support himself, often for silent films, blackface sketches, or other comedy acts. Later, as the result of successful compositions such as his Andalucian Suite for piano, he returned to the concert stage and toured internationally, fulfilling his childhood ambitions.

Lecuona’s music represents a sophisticated fusion of classical and popular elements, straddling the boundary between the two repertories. Often his works take inspiration from traditional sources of various kinds, including música guajiraand Afro-Cuban music. He was one of the first classically trained performers to create works based on Afro-Cuban themes. Lecuona should also be remembered as an internationalist, someone open to styles from many countries. His compositions are amazingly diverse; they include pieces inspired by Spanish dance music, zambas from Argentina (see Chapter 7), and foxtrots and blues-inspired music from the U.S.. He gained greatest recognition within Cuba for his musicals, often based on life in the colonial past.

The best-known experimental composer living in Cuba today is Leo Brouwer (b. 1939). Also renowned as a guitarist, conductor, and arranger, Brouwer came from a musical family (his great uncle was none other than Ernesto Lecuona!). He took classical guitar lessons from an early age and later studied in the United States, both at Julliard and at the Hartford School of Music. Since the late 1960s, Brouwer has gained international recognition as a composer of many kinds of music (symphonic repertoire, chamber pieces), but especially guitar works. His etudes, for instance, are idiomatically suited to that instrument, beautiful, challenging, and innovative.

Brouwer’s harmonic language is expansive and varied, incorporating everything from references to traditional or popular music from the Caribbean to extreme avant-garde timbres and unusual sonorities. More than virtually any other Cuban composer, he has demonstrated an interest in world music, adopting traditional Andean melodies, North Indian ragas, and African rhythmic patterns as sources of inspiration. Since 1981 he has been a principal conductor of the Havana Symphony Orchestra.

Brouwer’s work demonstrates his interest in expanding the sonic possibilities of the guitar. He has developed innovative ways of playing chords, for instance by using the thumb of his left hand on the fret board in addition to the fingers. He adapted muted pizzicato plucking techniques associated with violins and originally developed by Bela Bartók to the guitar. He may specify that performers employ harmonic overtones as part of melodic sequences or play on unusual parts of the guitar string, such as between the bridge and the tuning pegs. He has written guitar works to be played with a bow, as typically used on a cello or acoustic bass. Pedals (sustained notes) and ostinati of various kinds are common in his work. He has developed alternate guitar tunings for some compositions. On occasion, he has also used the body of the guitar as an instrument, instructing instrumentalists to rap or tap on the wood. In addition to writing for the concert stage, Brouwer has set music to some of the most famous Cuban films of all time including Death of a Bureaucrat, Lucía, Memories of Underdevelopment, and The Last Supper.

Among his most distinctive and original works is La espiral eterna (The Eternal Spiral) for solo guitar, an atonal, avant-garde work. Its music suggests an endless spiral in its rapid alternation of notes, and it is a virtuoso showpiece that reveals Brouwer’s remarkable talents as a performer as well as a composer.

The final artist discussed in this chapter is Michel Camilo (b. 1954), a Dominican whose work has consistently straddled the boundary between the worlds of classical music, popular music, and jazz. In this sense, his music is indicative of tendencies toward the fusion of elements from many kinds of music within and beyond the Caribbean in recent years. Camilo first trained at the National Conservatory in Santo Domingo where he studied classical piano and percussion, and shortly thereafter he took a job as percussionist in the National Symphony Orchestra (at age sixteen!). In 1979, Camilo moved to the United States, studying music at the Julliard School and Mannes College. 1987 marked his debut as a conductor of the Dominican National Symphony, interpreting works by Beethoven, Dvorak, and others. Camilo has appeared as a piano soloist with the Atlanta Symphony, the Copenhagen Philharmonic, the BBC Symphony Orchestra, any many other world-class classical ensembles.

In addition to his classical focus, Camilo has long demonstrated interest in both jazz and Caribbean traditional music. He took part in the International Montreal Jazz Festival in 1982 as a member of Puerto Rican Tito Puente’s band. Between 1982 and 1986 he performed regularly with Cuban jazz saxophonist Paquito D’Rivera and shortly thereafter collaborated with Cuban percussionist Ignacio Berroa as well. Camilo has composed prolifically both in the classical and jazz idioms, writing scores for television and film. One of his best known pieces, “Why Not,” is heavily influenced by North American jazz and helped win him a Grammy in 1983. Other works, such as Listening Example 5.10 , have been interpreted by jazz great Dizzie Gillespie and others.

Because Camilo’s work contains elements of both classical repertoire and Latin jazz, it would be useful to define the latter term briefly. As a general rule, the complexity of jazz lies in its harmonies and in sophisticated arrangements, while the complexity of much Afro-Latin music lies in its rhythms, its varied timbres, and the ways in which it layers particular melodic or rhythmic elements. Latin dance music tends to be harmonically simpler than jazz, and to consist of shorter formal structures (often two, four, or eight measure phrases) that are repeated many times in variation; it is closer to its West African roots in this sense. Styles of soloing often differ between jazz and Latin artists as well. Since they cannot necessarily rely on frequent harmonic changes to generate interest, Latin jazz performers rely more on innovative uses of rhythm, on repeated melodic shapes known as sequences, and other techniques.

The significant differences that exist between jazz and traditional Caribbean music made the two genres somewhat difficult to reconcile with one another. Probably the most common means of fusing them has involved reliance on jazz harmonies and big band jazz instrumentation supported rhythmic patterns, anticipated bass lines, and syncopated melodies derived from Cuban son, salsa, and other genres. Michel Camilo builds on earlier Latin jazz experimentation, molding it to his personal tastes and infusing the already hybridized idiom with elements from light classical repertoire such as the compositions of Ignacio Cervantes and Juan Morel Campos mentioned earlier.

This brief introduction to Spanish Caribbean music should serve as a point of departure as you continue exploring the traditions of various islands, regions, and composers on your own. There are countless styles of music that we have not covered well here, and that deserve mention: the danza and danzón, the cha-cha-chá and mambo, carnival music of various sorts, Latin rock and rap, Afro-Dominican drumming, etc. Though the overview has not been comprehensive, it provides some insights into the diversity and complexity of the region. It offers frames of reference for thinking about the interrelations between various styles and the cultural influences that have given rise to them. Finally, the chapter has emphasized the fundamentally mestizo nature of Caribbean cultures and music. Most West African- and Spanish-derived traditions performed today have blended over time, resulting in genres that reflect a uniquely New World reality. And hybridized culture as it exists today continues to assimilate new external influences from the hemisphere and beyond, leading to ongoing musical innovation and synthesis.

Austerlitz, Paul. Merengue: Dominican Music and Dominican Identity. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1997 (a social history of the merengue).

León, Argeliers. Del canto y el tiempo. Havana: Letras Cubanas, 1984 (an insightful Marxist-influence overview of Cuban music history).

Lizardo, Fradique. Danzas y bailes folklóricaos dominicanos. Santo Domingo: Museo del Hombre Dominicano, 1975 (a classic text on Dominican traditional music by one of the most prominent ethnologists of his day).

Manuel, Peter. Caribbean Currents, 2d. ed.. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006 (a textbook devoted exclusively to music of the entire Caribbean, including French-speaking, English-speaking, and Indo-Trinidadian traditions).

Moore, Robin. Music of the Hispanic Caribbean. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010 (a more detailed exploration of music and topics introduced in this chapter).

Pacini Hernandez, Deborah. Bachata. A Social History of a Dominican Popular Music. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1995 (emphasizes bachata’s origins and rise to popularity).

Quintero Rivera, Ángel. Salsa, sabor y control!: sociología de la música “tropical.” México : Siglo Veintiuno Editores, 1998 (a sociologist’s introduction to popular dance music in Puerto Rico).

Rivera, Raquel. New York Ricans from the Hip Hop Zone. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003 (on the history of Puerto Rican involvement in rap).

Rondón, César. The Book of Salsa: A Chronicle of Urban Music From the Caribbean to New York City. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008 (a brief history of salsa, and biographical info on prominent artists of the 1970s).

Vélez, María Teresa. Drumming for the Gods: The Life and Times of Felipe García Villamil, Santero, Palero and Abakuá. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2000 (the biography of an Afro-Cuban drummer).

Waxer, Lise, ed. Situating Salsa. Global Markets and Local Meanings in Latin Popular Music. London: Routledge, 2002 (selected essays on salsa).

Date of composition: [1980s]

Date of recording: 2002. Guateque. Havana: EGREM CD.

Composer/Lyricist: improvised décimas by Adolfo Alfonso and Justo Vega

Performer/Instruments: Alfonso, Vega, and the Orquesta Palmas y Cañas

Form: varied strophic

Tempo: brisk 6/8 time punctuated by pauses

What to Listen for:

Time

04:18 - 04:48

Track

A Tratas de ser ocurrente

B Festivo, irónico y ducho [2x]

B Porque a tí te gusta mucho

A Todo lo que no es decente

A Busca la luz del presente

C Que a todos nos ilumina

C Porque con esa rutina

D Esa guasa, y esa cosa

D Estás negando la hermosa

C Superación campesina

Translation

You try to be slick

Festive, ironic, smart

You so enjoy

What isn’t decent

Find the light of the present

That shines on us

Cause with that routine

Those jokes, and all that

You deny the beautiful

Progress of the farmer

Description

Vega begins singing

Time

04:49 - 05:13

Track

A No puedo negar la hermosa

B Superación campesina

B Que a toda Cuba ilumina

A En su marcha victoriosa

A Por tu forma caprichosa

C Me pintas como no soy

C Y más que seguro estoy

D Que lo haces para engañar

D Procurando desvirtuar

C Los palos que yo te doy

Translation

I can’t deny the lovely

Farmers’ progress

All Cuba shines over

Their victorious march

In your capriciousness

You describe me falsely

I’m more than sure

You’re doing it to deceive

Trying to deflect

The blows I’m giving you

Description

Alfonso

Time

05:14 - 05:43

Track

A Cuando te expresas así

B Insolente renacuajo [2x]

B Es cuando te miro abajo

A Muy por debajo de mí

A Pretendes negar aquí

C Mi capacidad humana

C Cuando tú eres tarambana

D Antes la presencia mía

D Por cobarde una jutía

C Y por miedoso una rana

Translation

When you talk like that

Insolent tadpole

I see you down below

Far below me

You try here to deny

My humanity

When you are a rascal

In my presence

A cowardly rodent

A frightened frog

Description

Vega

Time

05:44 - 06:12

Track

A Compárame a la jutía

B Y compárame a la rana [2x]

B Porque a mí no amilana

A En nada esa tontería

A Lo terrífico sería

C Mi querido compañero

C Es que en un tono ligero

D Cualquiera sin meditar

D Me quisiera comparar

C A este esqueleto rumbero

Translation

Compare me to a rodent

Compare me to a frog [2x]

It doesn’t scare me

All that silliness

What would be scary

My dear friend

Is that in a casual tone

Anyone, without a thought

Might compare me to

This skeletal rumba player

Description

Alfonso (the “skeletal rumbero” refers to Vega, since he is an older, thin man)

Time

06:13 - 06:25

Track

A Esa falta de respeto

B Una vez más ha probado [2x]

B Que eres un maleducado

A Un bruto, un analfabeto

Translation

With your lack of respect

You’ve proven once again

You’re uneducated person

A brute, an illiterate

Description

Vega

Time

06:26 - 06:39

Track

A Hay que ver que a este sujeto

C Siempre la ira a lo ciega

C Mas cuando el momento llega

D A pesar de su recato

D El viejo se pone sato

C Lo que pasa es que lo niega

Translation

This subject

Always rages blindly

Yet when the moment comes Despite his modesty

The old guy gets crafty

But he always denies it

Description

Here Alfonso jumps in, stealing away the décima

Time

06:40 - 06:44

Track

A Eso es mentira, mentira

B Hipócrita deslenguado

Translation

That’s a lie, a lie

Insolent hypocrite

Description

Vega tries again

Time

06:45 - 06:49

Track

B Para no verte agitado

A Toma jarabe de güira

Translation

Don’t get too excited

Take some güira syrup

Description

Alfonso jumps in a second time

Time

06:50 - 06:51

Track

A Cállate la boca, mira

Translation

Shut your mouth, listen

Description

Vega does the same to him

Time

06:52 - 06:55

Track

C Déjate de ser gruñón

C Poeta mariposón

Translation

Don’t be a whiner

You gay poet

Description

Alfonso, with an inappropriate slur

Time

06:56 - 07:01

Track

D No me vuelve a ofender

D Porque te voy a romper

C La boca de un pescozón

Translation

Don’t offend me

Or I’m going to break open

Your mouth with a punch

Description

Vega finishes the décima to applause

Time

07:01 - end

Track

Translation

Description

Brief instrumental coda

Title of piece: “Elegguá, Oggún, Ochosi II”

Date of composition: traditional

Date of performance/recording: 1999

Composer/Lyricist: anonymous

Performer/Instruments: 3 batá drums, singers

Form: The piece is structured around a series of praise songs in call-response form

Tempo: moderate triple meter

Function: Religious worship; in this piece, all songs pay homage to Elegguá

What to Listen for:

Time

00:00 - 00:10

Track

Ago, Elegguá abukenke [2x]

Translation

Praise to Elegguá, he takes so he can be rich

Description

The track fades in with the lead vocalist singing the first song; drummers are playing a variant of a rhythm called latokpa.

Time

00:10 - 00:15

Track

AGO ELEGGUA ABUKENKE [2x]

Translation

[same]

Description

The chorus responds with the same chant.

Time

00:15 - 00:21

Track

Translation

Description

The lead singer varies the melody.

Time

00:22 - 00:27

Track

Translation

Description

Chorus, same chant.

Time

00:28 - 00:32

Track

Abukenke, abukenke Amila topa loko

Translation

This chant mentions a particular incarnation of Elegguá

Description

Lead singer begins a second chant; drummers switch to a rhythm called abukenke.

Time

00:33 - 00:36

Track

ABUKENKE, ABUKENKE

Translation

[same]

Description

Chorus responds.

Time

00:37 - 01:19

Track

Elegguá demas unkio, etc.

Translation

Translation unknown

Description

Lead singer continues improvising phrases against the chorus. At about 1:12” the drums switch to ñongo.

Time

01:20 - 02:02

Track

BENI BENI MABE ECHUO BENE MABO, BENE BENE

Translation

Translation unknown

Description

The lead singer calls a third chant and the chorus responds. Chorus and soloist continue in alternation.

Time

02:03 - 02:53

Track

OBA KEYEN KEYEN ELEGGUA

Translation

Elegguá the child king

Description

A fourth chant begins, led in by the lead singer. The larger batás begin to improvise frequently.

Time

02:55 - 04:16

Track

CHENCHE MABO

Translation

Translation unknown; “chenche” means spiritual work

Description

The final chant in this segment begins. The tempo of the piece increases, and the drums improvise freely, imitating the “hotter” final sections of a religious event.

Title of piece: “En opuestas regiones” (“In Opposing Regions”).

Date of composition: 1910s

Date of performance/recording: 1999. Los Muñequitos de Matanzas. Rumba Caliente, Qbadisc Records QB 9005.

Composer/Lyricist: Sindo Garay

Performer/Instruments: The Muñequitos de Matanzas. Three conga drums, claves, chekeré, singers.

Form Binary: strophic section followed by montuno

Tempo: Moderate 4/4

What to Listen for:

Time

00:00 - 00:09

Track

Translation

Introduction

Description

Percussion instruments enter in staggered fashion, as described above.

Time

00:10 - 00:19

Track

Translation

Description

The lead singer establishes the key.

Time

00:24 - 03:18

Track

En opuestas regiones

Dos almas grandes nacieron

Siendo la Independencia

Su único ideal

También en opuestas

regiones cayeron

Las dos almas templadas

Dos héroes de gloria

De nombre inmortal

El apóstol de Cuba,

El verbo elocuente

En la inmensa Habana

Fue donde nació

El genio guerrero

Maceo en Oriente

Allá en Punta Brava

Perdió su existencia

Martí en Dos Ríos

De cara al sol cayó

Translation

In two opposing regions

Two great souls were born

Independence being

Their only ideal

And also in different regions fell silent

Two beating hearts

Two glorious,

Immortal heroes

The “apostle” of Cuba

Of eloquent tongue

In immense Havana

He was born

The brilliant warrior

Maceo in the east

There in Punta Brava

He was lost to us

Martí fell to his death

in Dos Ríos facing the sun

Description

The verse section of the song begins, sung as a duet. The two “opposing regions” discussed are the eastern and western extremes of the island.

Time

03:18 - 03:22

Track

Translation

Montuno begins

Description

A lead singer sets up the call-response vocals.

Time

03:22 - 03:24

Track

A estudiar cubano

Cubano mi Cuba ya es libre

A ESTUDIAR CUBANO

Somos libres y soberanos

A ESTUDIAR CUBANO

Evacuen si, evacuen ya

Ay pero evacuen si, evacuen ya, rumbero

EVACUEN SI, EVACUEN YA

Estamos evacuando a los de arriba

Y también a los de abajo

EVACUEN SI, EVACUEN YA

Evacuen la rumba que me esta llamando

Pero evacuen ya, yere

EVACUEN SI, EVACUEN YA

Translation

Start studying, Cubans

Cubans, my Cuba is now free

START STUDYING, CUBANS

We’re free and sovereign

START STUDYING, CUBANS

We’re getting them out, getting them now

Oh, but get them out, get them rumbero

GET THEM OUT, GET THEM NOW

We’re taking out the elites

And also those from below

GET THEM OUT, GET THEM NOW

Leave the rumba, it’s calling me

But get out now, yere

GET THEM OUT, YES GET OUT NOW

Description

Choral responses are indicated below by capital letters. The first chorus underscores the importance of knowing history; the second alludes to the U.S. and has anti-imperialist associations.

Title of piece: “Beso discreto” (Discrete Kiss)

Date of composition: 1941

Date of performance/recording: 2006 (Eliades Ochoa: Best of Buena Vista, Original Versions. Universal/Vene Music CD 653 146).

Composer/Lyricist: Miguel Matamoros

Performer/Instruments: Eliades Ochoa and the Cuarteto Patria/ Guitar, bass, bongo, maracas

Form: 2-part, strophic section followed by a brief montuno

Tempo: brisk duple

Function: entertainment

What to Listen for:

Time

00:00 - 00:09

Track

Instrumental introduction

Translation

Description

The melody is played on the guitar to the accompaniment of other instruments.

Time

00:10 - 00:31

Track

Una niña enamorada

Al novio con ilusión

Le dice muy apurada

“Bésame en este rincón”

El novio dice: espera,

“Deja que pase la gente

Que miradas callejeras

Son miradas imprudentes”

Translation

A girl in love

To her boyfriend

Says quickly:

“Kiss me in this corner”

The boyfriend says:

“Let the people go by first/ Cause folks on the street

stare imprudently”

Description

First verse.

Time

00:32 - 00:43

Track

Instrumental melody

Translation

Description

This is the same melody used in the introduction.

Time

00:43 - 00:51

Track

Como quieres que

Te bese, mi amor

Si la gente está

mirando de aquí?

Esperemos un momento mejor