Brazil is the largest and most populous country in Latin America; it is also fifth in the world in terms of territory (3,287,597 sq mi) and seventh in population (estimated at 217 million in 2024). This giant country is the homeland of peoples from a variety of ethnicities and backgrounds and Brazilians are particularly proud of their rich musical heritage, which draws from musics of Amerindian, European, and African origins, among others. Brazilian performers and composers have blended and transformed these traditions to produce a myriad of commercial popular styles that continue to expand the local musical scene. Within a large country populated by a variety of peoples, music making in Brazil has been particularly important as a channel for communal expression, as well as a marker of locality, regionalism, and nationality. Several Brazilian popular styles such as samba, bossa nova, Brazilian country music, and rock, have crossed the country’s borders to impact the international scene. Alongside other cultural icons such as soccer, music has served to showcase Brazilian culture abroad while at the same time helping to mediate communal participation and create internal bonds of citizenship.

Brazil is the only Portuguese-speaking country in the Americas, and the language has served well over the years to unify the country’s large and diverse population. Nonetheless, other languages have co-existed with the “official” Portuguese and play roles in Brazil’s vibrant cultural diversity. Descendents of European immigrants have maintained German and Italian dialects in communities in the South and Central Brazil, and the huge influx of Japanese immigration in the first half of the 20th century brought Japanese language and culture into the lives of residents of central Brazil, especially in the state of São Paulo. Although most commercial popular musics are sung in Portuguese, West African dialects are kept alive in Afro-Brazilian religious songs and in regional popular musics. In addition, some 180 native languages are spoken in contemporary Brazil. Amerindian words appear in the names of cities, rivers, and food, and in the lyrics of traditional songs. A national interest in reviving native cultures has also led popular musicians, such as singer and composer Marlui Miranda and metal bands Sepultura https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sepultura and Arandu Arakuaa, to record songs in Amerindian languages.

Brazil’s extensive territory is occupied by a myriad of landscapes, climates, flora, and fauna. Have a close look at the map above and you will see, for example, that over 60% of the Amazon forest lies in the Brazilian Western territory, and that the country also enjoys 4,600 miles of Atlantic coastline. Brazil spans four time zones and hosts one of the world’s most extensive river systems. In addition, the country’s several climate regions range from a vast tropical area in the North and Northeast coast, to semi-arid areas in the Northeast and central states, to subtropical and temperate climates in the Central-South, where extensive coastal mountains are covered by subtropical forests.

Throughout the centuries, the splendor of the local landscape has appealed to European explorers and colonizers. When, in 1500, the Portuguese Pedro Alvares Cabral arrived on Brazil’s Northeast coast, his reports included enthralled descriptions of the “discovered” land’s grandeur, beauty and, of course, commercial potential. The country’s mesmerizing landscape has ever since been depicted in historical reports, poetry, and novels with an intense pride and has been transformed into an important icon of Brazilian culture. Landscape, nature, and its sounds were a vital source of inspiration for the romantic nationalistic music of 19th– and early 20th– century Brazilian classical composers. The country’s beauty has also been a unifying theme in the lyrics of Brazilian popular music, from urban sambas and Bossa Nova to rock and hip-hop songs.

But while landscape and language have served to promote shared feelings of Brazilian nationality, they have also set Brazil apart from the rest of the continent. Today social media allows people all over the world to communicate and learn about one another, but less than one hundred years ago communication and transportation systems could not overcome Brazil’s geographical hurdles. Although Brazil shares borders with most South American countries (Ecuador and Chile being the exceptions), the vast Amazon forest and the Andes mountains in the West have historically hindered Brazilians’ cultural exchanges with their Latin American neighbors. Furthermore, with the Amazon forest covering 1/3 of the country’s territory, the majority of the Brazilian population lives in large cities situated on or near the coast, where large ports maintain the country’s economic, political, and cultural ties to Europe and Africa, perhaps more so than to Spanish-speaking Latin America. Consequently, Brazil’s history is marked by a constant flow of European consumer goods, European and West-African cultures, and music.

Explored and settled by the Portuguese, Brazil’s colonial history (1500-1822) intensified this divide. With political and commercial policies that favored commerce and trade over settlement, throughout the colonial years the Portuguese exploited Brazil’s natural resources for the economical gain of the motherland, not for the benefit of the colony. As a result, colonial Brazil did not harbor strong cultural institutions that helped to recreate European music on its side of the Atlantic. No printing presses were allowed in the colony and no institutions of higher education were created in Brazil until the first decades of the 19th century. The discovery and rush for gold in the second part of the 18th century surely caused a large immigration to areas of central Brazil and boosted the local musical production, as we learned in Chapter 3. Even so, when compared to the richness of the European music that flourished in Spanish speaking countries during colonial times, Brazil lingered much behind.

In 1808, the Portuguese monarchs moved their court from Lisbon to the Brazilian capital, Rio de Janeiro, to avoid Napoleon’s army, then invading Portugal. The arrival of the court in Brazil was a unique political and historical event in the Americas. As the Portuguese royal family sought to foster a European empire in the New World, they drastically changed the policies that had restricted the growth of their South American colony. Later, in 1822, it was Pedro I, heir to the Portuguese Braganza family, who declared Brazilian independence from Portugal. The monarchical regime continued when his son Pedro II ascended to the throne in 1840, and was not disbanded until the proclamation of the Brazilian republic in 1889. While, during the 19th century, wars for independence in Spanish-speaking countries resulted in political and social unrest, Brazilian independence began on a politically stable foundation that favored the development of European-style institutions and a constant flow of the latest European musical trends to Brazilian cities. As a result, a myriad of European musics found fertile ground in Brazilian cities, from Italian opera to traditional musics derived from the Iberian Peninsula. Some of these traditions have been maintained almost unchanged, while others have been transformed into musical manifestations that reflect the new context of the country’s multicultural society.

But the Portuguese did share several practices with other European colonizers in the Americas. Like the Spanish, upon their arrival on Brazilian shores the Portuguese started by enslaving natives for agricultural work. Cultural conflicts, forced labor, and widespread disease led to the deaths of millions of Amerindians. It is estimated that about four to five million natives from some 1,000 different cultural groups were living in Brazil when the Portuguese arrived. Only about 370,000 Amerindians from about 220 cultural groups remain today. The Brazilian natives, which are dispersed throughout the country, belong to four large ethnic groups, Tupi, Gê, Arawak, and Carib. Some communities were integrated into mainstream Brazilian society and settled in large cities, others have maintained indirect contact with the culture of the colonizers, while others, living in remote regions, have managed to keep their cultural and musical heritages almost intact.

Another similarity between Spanish and Portuguese colonization was the enslavement of Africans to work on sugar cane and coffee plantations in the Brazil’s Northeast and central coast. Under Portuguese colonial rule and as a monarchy during the 19th century, Brazil imported and enslaved over 4 million Africans, more than any other single country in the Americas. Although the slave trade was formally abolished in 1850, illegal traffic continued for several decades and thus the actual number of Africans brought to Brazil is believed to have been well over 5 million. Although in the 19th century African and Afro-Brazilians were a majority of the population, under a strong monarchical rule Brazilians managed to maintain the institution of slavery until 1888, decades after abolition in most Latin American countries and the U.S. According to the latest demographics, in today’s Brazil Afro-Brazilians, mulattos (descendants of African and European), caboclos (descendants of African and Amerindian), and mixed-race individuals account for some 45 % of Brazil’s population.

The Africans brought to Brazil were mostly from West African countries such as Nigeria, Benin, and the Portuguese colony of Angola. The majority belonged to Yoruba and Bantu-Ewe cultural groups and brought with them a wide gamut of African religious and secular musical practices. The large number of Africans taken to Brazil, the endurance of slavery, and a close and lasting interaction between Africans and white Europeans in urban areas resulted in a strong influence of African culture on mainstream Brazilian culture. African traditions are particularly felt in the Northeast, an area that holds the largest concentration of people of African descent outside Africa. As in Cuba and other countries in the Caribbean, Brazilian culture is deeply marked by a long history of contrasts and clashes between the cultures of the Africans and Europeans. But Brazilian culture is also distinguished by a conspicuous intermingling of these cultures, a complex mix that characterizes the core of the country’s musical scene. This intermingling can be seen most clearly in a variety of popular musical styles that fuse West African musics, instrumentation, and performance practices with traditional musics inherited from Portugal and a myriad of European urban popular musics transplanted to Brazil during the 19th century.

With the abolition of slavery in 1888 and the proclamation of the republic in 1889, Brazil finally got started on the process of breaking away from the Old World. Growing industrial production, the rise of the local economy, and the growth of a middle class concentrated in large cities helped shape the path towards modern Brazil. At the beginning of the 20th century, and especially during the government of populist president Getulio Vargas (1930-1945), Brazil witnessed a strong wave of nationalism—a political and intellectual movement that supported artistic expressions symbolic of a new and unified nation. The movement was born as a formal celebration of the local mix of ethnicities and cultures, a mix in which the European and African elements were the main threads in the general fabric of a Brazilian national culture. Throughout the 20th century, the idea of Brasilidade (Brazilianness), of something that identified the uniqueness of Brazilian culture, has been vital in the understanding of local musical traditions and has also been a constant force in the production and consumption of popular musics. Three generations of classical music composers also contributed to the dissemination of nationalism as they explored a variety of local traditions, and the Afro-Brazilian heritage in particular, to express musically the Brazilian culture.

Although a 1964 military intervention held Brazil back politically, the country re-emerged as a democracy in 1985 and continues to grow as a major political and economic power in the Americas. Today Brazil has the 8th largest economy in the world, a wealth that is concentrated in the hands of a few. As a country of extreme richness and accentuated poverty, the harsh social divide has also become part of the Brazilian culture. If hybrid popular musical styles have contributed to symbolize a unified country within a nationalistic political agenda, a rich variety of regional musics have also played a role in highlighting Brazil’s social and ethnic divides. Finally, contemporary Brazil is a young country: 50 percent of its population ranges from 20 to 40 years of age, the great majority living in large cities where access to an increasingly advanced system of communications puts them side by side with other cosmopolitan youngsters around the world. Thus, contemporary Brazilian musical life reflects its youthful population’s desire to belong to and to contribute to the musical “global village.”

As we start to explore some of these musics, keep in mind Brazil’s ethnic and cultural richness, geography, history, and cosmopolitan experiences, as well as its ethnic mix and social divides. These elements overlap and interact in complex ways, and result in musical styles and performance practices that often cross the boundaries of traditional musical classifications, such as popular, religious, traditional, and classical musics. In addition, in urban settings Brazil’s Native, African, and European heritages appear diluted in a variety of original musics in which tradition and modernity go hand in hand.

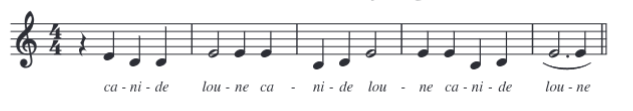

In 1557, the French Calvinist missionary Jean de Léry ventured inland from the central Brazilian coast and lived among the Tupinambá Indians for almost a year. He wrote about what he saw and heard and in 1558 published a book that included reports about the lives, music, and dance of the Tupinambás. Léry’s publication is invaluable because it includes the earliest transcriptions of Amerindian songs in the Tupi language and thus gives us a glimpse of the nature of their music when European explorers first arrived in Brazil in the 16th century. The song Canidé-ioune transcribed by Jean de Léry (Musical Example 5:1) is a Tupinambá homage to a bird with yellow feathers. The song has been re-printed in several publications over the centuries and continues to be revived in a variety of versions, the most famous of which is an arrangement for chorus done by 20th-century Brazilian composer Heitor Villa-Lobos. Thus, this Tupinambá song collected in the 16th century continues to remind Brazilians about their native roots.

During colonial days and in the 19th century, other explorers traveled to remote areas of Brazil and published reports on native musical practices, but the culture and music of the Brazilian Amerindian only began to be studied with academic rigor in the last fifty years or so, when a new wave of young ethnomusicologists has set out to explore the musical practices of individual Amerindian groups. However, considering the wide range of native cultures spread over an extensive and often rough territory, ethnomusicologists still have a lot of work ahead of them before we can fully comprehend such a rich musical culture. In this text we can just glance over an amazing variety of native musics. Nonetheless, there are some commonalities among the various Amerindian musical practices, especially among the groups living in the large Amazon basin, that can be studied as general traits tying various native musical cultures together.

In terms of performance practices, we know that music making is usually a social activity and serves to organize social interaction. As a result, there is a prevalence of communal singing and group instrumental performances in which there is no distinction between performers and audiences. Instances of solo performances are also found in the Amazon basin and are often associated with rituals to connect with the supernatural. In addition, the body is an essential part of the native’s musical expression, as there is an intrinsic link between musical performances, singing, and dance. Not unlike most cultures around the world, to the Brazilian natives the meaning attached to music is directly linked to the music’s role in specific ritualistic and social functions; thus, their rich musical tradition is comprised of repertories associated with celebrations, commemorations, fishing, hunting, work, religious rituals, and cure songs used to extract diseases believed to be caused by supernatural forces. The musical repertory is passed down orally from generation to generation, a job often performed by the Shaman, a religious and/or political leader. Music making is also a strong marker of gender roles. In several groups in the Amazon basin, for instance, women are not allowed to play flutes, and in some rituals, not even permitted to see their performances.

We can also identify characteristics common to the music itself as it is performed in the Amazon basin:

Our listening example is a field recording done by Jean-Pierre Estival. The Assurini (Surini) is a Tupi-Guarani-speaking group who live on the bank of the upper Xingu River, a large tributary of the Amazon in the Northern state of Para. The group’s economy is based on fishing, hunting, agriculture, and unique clay pottery produced by the women. The Tiwagawa ritual of the Assurini is one of several native rituals with song and dance that link animals as “guardian spirits” and humans. During the ritual the Assurini sing and dance to invoke the jaguar’s spirits (Tiwá=jaguar spirits) and prepare for war. Jaguars are a constant presence in the region and, as powerful hunters, they are quite respected. In this excerpt, you will hear two songs that are part of a long sequence of songs performed during the ritual. In this short example we can identify some of the musical characteristics noted above: communal singing; foot stomping to mark a constant pulse; pentatonic scale; constant repetition of a short melodic line; isometric structure; predominance of descending line with the lowest note of the refrain functioning as a tonal center; syllabic text setting interspersed with speech; heterophonic texture caused by individual variations of the melodic line; and an accompanying vocal drone.

Musical instruments are manufactured by hand and as a result they are not uniform and come in a multitude of sizes and shapes. They are made from a variety of local materials such as wood, clay, coconut shell, animal horn, bone, bamboo, and, when available, conch shell. A great deal of work and care is put into the construction of musical instruments. They are often ornately decorated with leaves and/or feathers, and colorful designs are drawn with paints extracted from seeds. Among the groups living in the Amazon basin, there is a preference for musical instruments from the aerophone and idiophone families. Some scholars believe that cordophones were not introduced to Amerindian culture until the arrival of the Jesuits during colonization. Membranophones are also uncommon in the Amazon basin. Instead, hollow log drums serve to accompany celebratory and Shamanistic rituals. Although several kinds of drums with stretched animal skin are found in the North, the use of membranophones by Tupi groups living along the coast is believed to be the result of contact with Europeans.

Aerophones come in two generic types: those in which the sound is produced by agitating a material, usually wood in the air, and those where sound is produced by blowing. Examples of the earlier are the zumbidores, or zunidores, instruments made out of a hollow wood or bamboo stick linked by a string to a flat wood panel that is twisted several times in the air to produce a buzzing sound. Examples of the latter are flutes and whistles; vertical flutes, with and without reeds, and panpipes are the most common. There are also horizontal flutes and a variety of vessel flutes, like ocarinas, in which the sound resonates in the entire cavity of the instrument.

Flutes are special instruments to Amerindians because they can be used to imitate birds and other nature sounds. They are also essential in rituals associated with fish and fishing, a crucial activity to many communities in the Amazon basin. Flutes are widely used in religious rituals and are believed to connect humans to their spiritual ancestors. One group that uses flutes in several rituals is the Kamayuras (Kamaiurás, Camaiuras), a community of some 355 people who live on a large reservation in the area of the Upper Xingu River. The Kamayuras are known for their use of the uruá flutes, a long double-flute, the larger cane tube measuring approximately 7 feet, and the shorter about 5 feet. Uruás are used in rituals to reach the Kamayuras’ ancestral spirits and to honor the dead, to celebrate the rite of passage to puberty, and to collectively commemorate marriage. During these rituals, male performers move from house to house playing the uruá, and are joined by women and children during the final collective festivities.

Idiophones are also widely used by all Amerindian groups. They come in a wide variety of forms, but shakers are the most common. Attached to the ankles, wrist, or waist as bracelets and belts, they look like small ornaments made out of seeds, animal teeth, or claws. These small shakers can greatly expand the sound of foot stomping, and when attached to stamping tubes or a wooden stick they mark the rhythm as accompaniments to dancing and/or singing. Another very common shaker is the maracá (maraká, maraca), usually a gourd filled with seeds. This instrument, which continues to hold its original Tupi name throughout Brazil, is essential in music making to accompany dance, but is also vital in Shaman rituals where the instrument symbolizes spiritual power.

Amerindian music may be perceived as simplistic or monotonous by those used to an array of social media apparatus that exponentially expand sounds and musical possibilities. Nonetheless, we invite you to look at and listen to Amerindian music in a context that does not require complexity, at least not at an immediate level. Native musical performances are part of a set of worldviews founded on an intrinsic connection between human beings and nature. However, if this connection is optimistically perceived as “natural,” there is still a lot to be investigated and learned about a complex set of cultural relations created by a variety of different timbres, vocal emissions, and instrumental sounds that communicate subtle human interactions and social structures and that are very specific to each of these small native communities.

We should also keep in mind that several musical traits of the Brazilian natives have blended with European and African traditions and are manifested in the caboclo culture and music of the North and Northeastern regions. In addition, the idealized image of the Brazilian Indian as pure and authentic, explored in 19th-century romantic classical music, has been retained to this day in popular culture through a kind of “native nostalgia.” The figure of an idealized native is recreated every year by singers and dancers who dress in native “costumes” and parade during carnival celebrations throughout Brazil.

Finally, as a result of recent efforts to mitigate global warming and pollutants, popular musicians from all over the world have visited and performed with Amazon groups, and brought them to larger cities to perform in concerts for the preservation of rain forests. The most well-known example is the singer/composer Sting, who visited the Xingu reservation in the late 1980s and performed with the Xavante group. More recently, Brazilian jazz performer Egberto Gismonte has also appeared in concert with the Kamayuras; Brazilian metal band Sepultura visited the Xavante in the 1990s and included some of their sounds in their famous recording Roots (1996) [Available on Spotify https://open.spotify.com/search/Sepulturaa%20Roots]. But rather than wait for outside celebrities to bring their culture and pleas into the spotlight, musicians from several indigenous groups have inserted themselves in the local musical scene, performing, recording, and sharing their work on social media, and making a rich contribution to Brazilian popular music of various styles, from rock, rap, and pop, to creative blending of these with their traditional musics. Their strong presence in the contemporary scene can be seen in sites like https://kalamidade.com.br/20-artistas-indigenas-que-fortalecem-a-musica-contemporanea-parte-1/ and https://novabrasilfm.com.br/notas-musicais/vozes-indigenas-para-acompanhar-na-musica-brasileira-confira-10-musicas , and many others easily accessible on social media.

The Iberian Peninsula’s long-held traditions of outdoor festivities, parades, and dramatizations with music and dance are alive and well in contemporary Brazil. Sacred music dramas recounting passages of the Catholic Church calendar were vital during colonization as a tool for converting natives and Africans to Catholicism, and they survive in today’s Brazil in several regional variations. For example, the Folia de Reis, asacredfolk drama recreating the Christmas Cycle, can be found in small towns in rural areas as well as in working-class neighborhoods in large cities. The celebrations of the Folias start on December 24 with the announcement of the birth of Christ, and end on January 6 (Epiphany), the Dia de Reis (Day of the Three Kings). Usually on the last day of the cycle people join the members of the Folias in large outdoor festivities that include musical performances, dances, food, and drinks.

The Folias typically consist of groups of 6 to 8 people who sing and dance from house to house and in return receive food, drinks, and sometimes donations in the form of money. But Folias can also be organized into larger groups of 20 plus participants that put on elaborate parades and whole-act dramas. Each Folia has original songs and different performing styles to greet the residents. The groups sing toadas, strophic songs with lyrics inspired by biblical passages, accompanied by several instruments; in the Northeast the zabumba, a double-headed bass drum, is the most popular, but the ensembles typically also include a caixa (snare drum), guitar, sanfona (accordion), and pandeiro (tambourine); in the Central and Southern regions a guitar, a cavaquinho (four-string instrument, similar to a ukalelê), or a rabecca (violin) are sometimes also included.

Iberian traditions are also evident in Brazil in a number of secular dramatic dances, of which the bumba-meu-boi is one of the most popular. Found in different formats in small towns and rural areas throughout Brazil, the bumba-meu-boi is a tradition that goes back to colonial days when Brazilian cattle farms were staffed with slave labor. But although the dramatization derives from the Iberian dramatic dances, the bumba-meu-boi plot is a Brazilian creation that connects the European, African, and Native traditions. The drama metaphorically recreates the agrarian cycle by enacting the kidnapping, death, and resurrection of an Ox. The plot, which is told in a variety of ways throughout the country, involves a Portuguese master and his wife, a slave (Pai Francisco) and his pregnant wife, and other Afro-Brazilians and native slaves. As the story goes, one day Pai Francisco’s wife craved to eat an Ox’s tongue, in particular the tongue of her master’s favorite Ox. Pai Francisco kills the Ox to satisfy his wife, but as a result falls in disgrace with his master. The master orders Francisco to bring the Ox back to life, which he does with the help of native medicines and sacred rituals. The animal awakes and everyone dances through the night. Some scholars believe that the bumba-meu-boi folk drama depicts the interaction among social classes in colonial Brazil, in particular denouncing slave owners and ridiculing the ruling class.

The bumba-meu-boi tradition is part of the Ciclo Junino (June Cycle) and is most prominent in the North and Northeast, where the drama unfolds in elaborate outdoor parades that re-tell the plot in original ways. The Ox, the main character of the drama, usually makes a dramatic appearance as a dancer in the middle of the parade covered by a colorful and ornate Ox costume. The Ox dances, is killed, then is resurrected, and everyone sings and dances together. During the dramatizations participants sing strophic songs, toadas do boi (Ox songs), in responsorial style accompanied mostly by percussion, especially the bass drum zabumba and pandeiros, but the ensemble can also include a sanfona, pifano (flute), guitar, and maracas. In the Northeastern state of Maranhão, bumba-meu-boi performances are a major attraction during the month of June. Their bumba-meu-boi groups are famous for their large percussion ensembles, which include: the characteristic pandeirão, alarge frame drum that can range from 24 to 32 inches in diameter; matracas, two hardwood sticks, similar to a Cuban clave; and tabor-onça (friction drum). Each group has its own sotaque (style), characterized by unique rhythmic patterns, instrumentation, and song style. Usually, the matraca and maracas provide a time-line that consists of alternating duple and triple rhythmic patterns, resulting in constant hemiolas. The pandeirões provide a bass pattern as well as improvised rhythms that enrich the overall sound. Some of these bumba-meu-boi sotaques can be heard in the State of Maranhão web site. In the State of Amazonas the Ox celebrations have been adapted and transformed to include native symbols and myths, as well as imagery from the Amazon River and its natural environment. Recently, these traditions have been enhanced in a most exquisite June celebration of the Ox in the city of Parintins, where Ox songs highlight the caboclo culture, and modernize the traditional musics by adding updated electronic sound apparatus to the already mixed celebration.

In depth

With a population of some 100,000 inhabitants, the city of Parintins is situated on an island in the Amazon River between the State capital of Manaus and the city of Santarem in the State of Para. Even though Parintins can only be reached by boat or air, recently it has attracted businesses from all over Brazil and abroad. The reason might be its location as a commercial hub in the Amazon river. But some believe that Parintins has become the center of attention for outsiders because of its elaborate June celebrations of the Ox. In Parintins the bumba-meu-boi tradition is known as boi-bumbá and, as with similar traditions in the Northeast, the Ox is the central attraction of outdoor parades that involve music and dance. The Boi-bumbá dramatizations in Parintins have grown to gigantic proportions to become major mega folk events that attract some 100,000 spectators every year, doubling the city’s population.

The celebration includes a competition between two groups: the Caprichosos and the Garantidos. These groups have existed since 1913, but it was not until the 1960s that the competition between them was formalized. Since then, during the month of June red and blue, the colors of the Caprichosos and the Garantidos, color the streets of Parintins and serve as banners for excited supporters. In 1988, the celebrations moved to the bumbódromo, a stadium in the center of the city constructed in the shape of an Ox. The bumbódromo accommodates some 35,000 spectators who gather to see the two boi-bumbá groups, with 4,000 members each, compete with one another with luxurious costumes and floats, much like the outdoor parades during Carnival in Rio de Janeiro (see next section). Meanwhile, the rest of the people celebrate the re-enactment of the killing and resurrection of the Ox by dancing freely in the streets of Parintins.

The boi-bumbá celebration of Parintins has a plot similar in its basic themes to the bumba-meu-boi. But in the Amazon it has acquired several Amerindian elements. The native “motive” is a constant presence in the dramatization, especially the Pajé’s (Shaman’s) role of resurrecting the Ox through music and dance. Depictions of nature dominate the decorations, floats, and costumes, and the lyrics of songs recount the myths of the Amazon forest, whether or not associated with the Ox. In the bumbódromo, the European and the native are not only wedded but also modernized, as electronic equipment, laser lightshows, amplifiers, and electric instrumentation bring the Ox celebration of Parintins into the 21st century.

While the red and blue teams parade they sing stanza and refrain toadas. Some toadas are part of a traditional repertory passed down orally, but lately professional composers have begun writing new toadas every year. These “toadas do boi” (Ox songs) are recorded in local studios and released every year locally. Unlike the bumba-meu-boi of Maranhão, in Parintins these songs are accompanied by brass, strings, and electronic instrumentation and a percussion section that produce mellowed rhythms resembling Caribbean merengues (see Chapter 10). Recently, some of these Ox songs have begun to cross over and reach the larger pop music market. Still, during the parade the beat of zabumbas, pandeiros, and maracas in duple meter are a constant in the large percussion groups that can include 400 performers. The toadas of the Ox can be heard in the Parintins website (www.parintins.com), where you can also browse through pictures and videos of the parade. For a video of the2019 parade check.

The tradition of sung improvised poetry of the Iberian Peninsula is also alive in several Latin American countries. In Brazil it is known as cantoria, a tradition that identifies the rural, peasant roots of wandering singers, cantadores, whose lyrics are improvised over the strumming of a viola, a string instrument smaller than the guitar with five double metal courses. Violas are crafted by a handful of local manufactures out of local pinewood, although recently a different kind of viola with an internal metal resonator has been the preferred type of modern cantadores. Their tuning varies depending on the region, but cantadores usually prefer an open tuning of a D chord. As they improvise their verses in song cantadores strum only one or two chords on the viola: the D chord, which serves as a drone to their declamatory style of singing, or the D and A. The melodies, set syllabically to the improvised text, are built on a limited number of notes and are sung with a characteristic raspy and high-pitched vocal style. In the Northeast, cantadores are part of the daily scene in both rural and urban areas. Their verses cover a range of issues from their peasant world, like life on a farm, local gossip and politics, but cantadores also sing about contemporary social issues and even international relations, as their songs’ lyrics highlight their well-rounded knowledge. There are several ways that cantadores organize the meter and rhymes of their verses, the sextilha, six-line verses, being the easiest and most common. The example below is a poem with three verses of ten lines each called décimas; here a poet from the State of Ceará talks about contemporary issues such as world climate changes. Let’s look at how the rhyming scheme works in the Portuguese language:

A.- Reciclar é muito importante Recycling is very important

B.- E precisa-se educar o povo, It’s necessary to educate the people

B.- começando já desde do ovo, Starting with the early egg

A.- num processo muito urgente, In a very urgent cycle

A.- porque a terra tá muito doente; Because the land is very sick

C.- com terremoto e furação; With earthquakes and hurricanes

C.- os animais estão em extinção. And animals are in extinction

D.- Já está faltando oxigênio, There is not enough oxygen

D.- não alcançamos novo milênio. We’ll not reach another millennium

C.- A terra será um grande vulcão. Because Earth will turn into a volcano

A.- O ozônio também está sumindo, The ozone is disappearing

B.- está acabando com as geleiras, It’s melting the glaciers

B.- e ainda com as cordilheiras. And also the mountains

A.- O mar a terra está invadindo; The sea is invading the land

A.- os oceanos já estão subindo, The ocean levels are going up

C.- têm causado tanta destruição And have caused a lot of destruction

C.- do Canadá até o Japão. From Canada to Japan

D.- A culpa é dos seres humanos, The human beings are to be blamed

D.- que em breve, dentro de poucos anos, who, very soon, in a few years

C.- da terra desaparecerão. Will disappear from Earth

“Vamos reciclar o planeta” (Let’s recycle the planet) by Henrique César Pinheiro Outubro/2006. Translation by Cristina Magaldi (Usinas das Letras http://www.usinadeletras.com.br/exibelotexto.phtml?cod=9474&cat=Cordel&vinda=S)

Cantadores often confront one another in desafios (duels) with fights of words, double entenderes, clever rhymes, and reciprocal put-downs, where they display their general knowledge, arguing capabilities, memorization, eloquence, diversity of themes, and talent in creating comic and satirical verses. Audiences in bars or informal gatherings in town squares participate by challenging the duelists, suggesting topics and rewarding them with change passed around in a small tray. As the tradition has spread from rural to urban areas, and even to large cities like São Paulo and its surroundings, national competitions have gathered the most skilled cantadores and showcased them on radio and popular TV shows. Since the 1960s, cantadores have been receiving growing interest from the pop music industry, where singers like Elomar and Zé Ramalho have used the cantadores’ style to appeal to a large audience. In addition, the similarity between the techniques of cantoria and U.S. rap, the improvised poetry over a repetitive base, has not escaped the attention of the younger generation, and has created much debate about the “true” Brazilian origin of rap. Regardless, young popular musicians from Recife, the capital of the Northeastern state of Pernambuco, have been very successful in wedding the two traditions. The rap group Faces do Subúrbio, for instance, has achieved great success with songs that explore improvised rhymes accompanied by drum machines and strong bass lines.

The tradition of the wandering singer accompanied by violas has also served as a symbol of identity in Central and Southern Brazil, where música caipira, or hillbilly music, has grown to become a best seller in the Brazilian pop music market. Música caipira can be understood as the music of the rural peasant, but it has also crossed the rural/urban boundaries because of a heavy migration of peasants to large cities. In música caipira, a duo sings in parallel thirds to the accompaniment of violas, guitar, and/or sanfona. Their verses are not improvised, but strophic songs about romance and life in the country. Singers of musica caipira do however sing with the same characteristic nasal, high-pitched vocal tones of the wandering cantadores and the sound of the viola is often present or implied. As música caipira reached the air waves, it spawned hits in large cities and became known as musica sertaneja, or country music. New duos have popped up in the growing market and have wedded the sound of the viola with electronic instrumentations and bass drums, string orchestras, and updated sounds produced in state-of-the-art studios. One of the most successful duossertanejos of the 1980s and 1990s is Chitãozinho & Xororó. They have dominated radio and TV and sold millions of records in Central and Southern regions. Their music has also reached the international market; they have recorded songs in Spanish and collaborated with famous U.S. stars like the Bee Gees and Reba McEntire. As with U.S. country music, most duos sertanejo’s songs focus on romance and nostalgia for life in the country. Chitãozinho & Xororó have influenced a host of new duos sertanejos who dominate the Brazilian airwaves today and that are widely available in social media, including the duo Zé Neto & Cristiano, who are one of Brazil’s most well-known contemporary sertanejo groups. Check their site for videos, shows, and recordings, which are also available on Spotify and YouTube.

Let’s start learning about the rich African heritage in Brazil with a sacred musical tradition from a religion called Candomblé. African religions have strong influences in other Latin American countries, especially in Cuba, as we will learn in Chapter 6. But in the Brazilian Northeastern state of Bahia, the pervasiveness of African religions is such that the state’s capital, Salvador, is said to be for African religions the equivalent of the Vatican for Catholicism. Thus, Salvador is the center of all musics derived directly or indirectly from African religious practices, not only in Brazil, but in the Americas. And Candomblé is the most distinctive of all these African religions because it has preserved direct links with its original West African sources, in particular those of the Yoruba culture.

Candomblé followers worship a supreme being Olorum, with orixás, or deities, as intermediaries between the worshipers and the God Olorum. Orixás are mythological figures that symbolize all parts of nature, as well as spiritual ancestors. The high point of the Candomblé ritual is when initiates pass into a trance and a state of spiritual possession where the orixá takes over their bodies to communicate with and bless the worshipers. Orixás’ animistic characteristics are represented in Candomblé by different colors, special clothes, types of food, and particular objects or symbols; for example, Yemanjá is the female orixá of the oceans and her preferred colors are blue and white. Each orixá is also associated with specific songs, rhythmic patterns, and dance movements. During the ceremony the initiates, practitioners specially trained in the symbology of the ritual, dress in the clothes and colors of each orixá and place his/her favorite food at the altar. Then they sing and dance to the sound of sacred drums, the atabaques, to evoke that orixá and to eventually get him/her to possess their bodies. Thus, song and dance are essential to the Candomblé religion as they have a vital role in the act of trance and possession, which is an indication of the presence of the orixá.

It is the job of the Candomblé religious leaders, the babalorixá (male) and ialorixá (female), to know and teach the associations between each orixá and their songs, as well as the placement of each song within the liturgical sequence of the ritual. Worshipers sing in the Yoruba language and in responsorial style, where the leader makes the call and the initiates and participants respond in unison with short phrases and/or interjections. Because drumming plays a crucial role in “calling” and communicating with the orixás, the main drums, the atabaques, are considered sacred instruments. They undergo a ritual baptism and are painted with special colors and decorated with colored scarves, beads, and other materials associated with specific orixás.

Atabaques are cone shaped, single-headed drums played with a wooden stick or, depending on the tradition, with a combination of hands and sticks. They come in three sizes: from the lowest to the highest pitched they are called Rum, Rumpi, and Lê. The master drummer, or alabê, is the second in importance in the Candomblé hierarchy. He plays the Rum, the largest and most important drum, and provides the basic rhythmic patterns, gives clues for changes in rhythm and drives the general tempo for singing and dance movements performed by the initiates. The alabê also assists in leading the singing and directs the improvisations played on the rumpi and lê. The Candomblé musical ensemble also includes an agogô, or double-bell, and sometimes a xekerê or afoxé, an idiophone made of a calabash gourd covered with beads. Each instrument has a small, improvised rhythmic pattern that is repeated several times in ostinato.

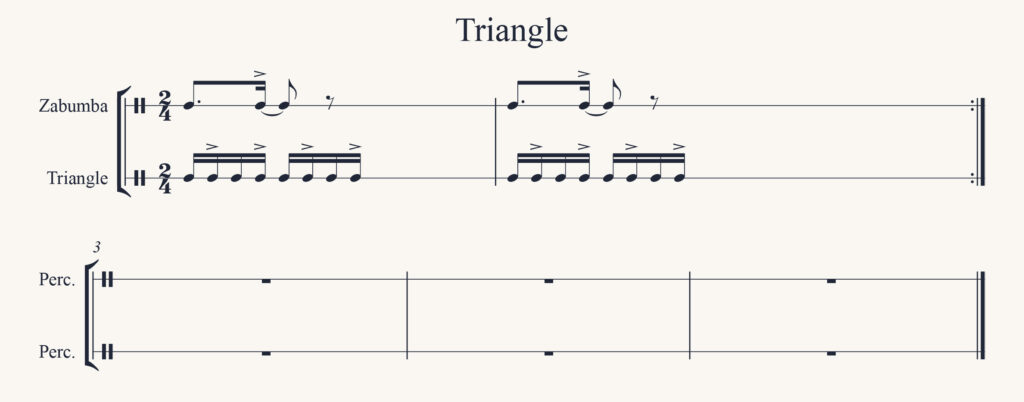

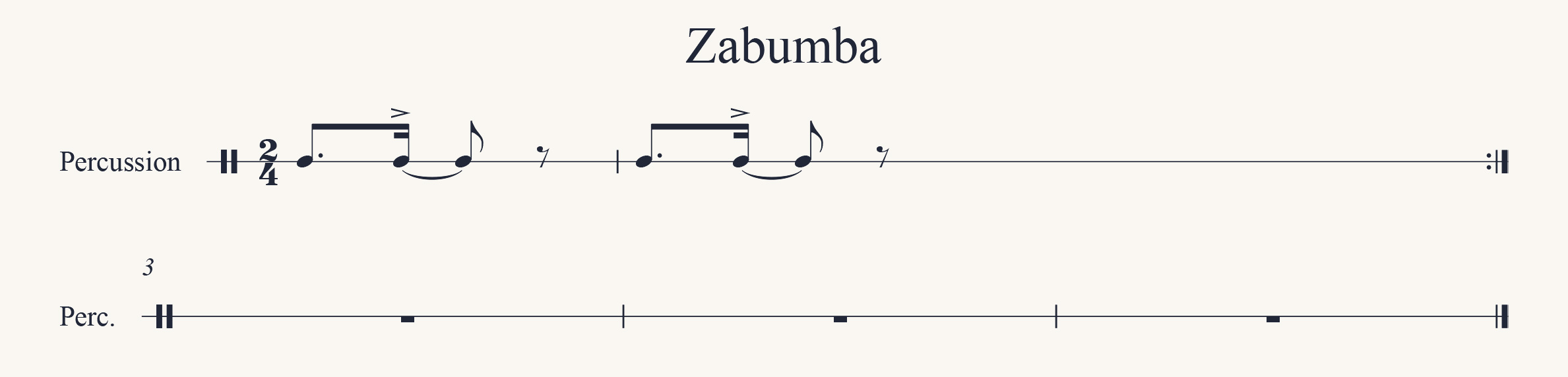

Ethnomusicologist Gerard Béhague studied the liturgical functions of songs within the Candomblé ritual and transcribed several rhythmic patterns associated with specific orixás. Musical Example 5:2 shows a section of the avaninha rhythm, which is performed by an ensemble of atabaques and agogô at the beginning of the xirê, the public ceremony of Candonblé. This rhythm is performed by percussion as the initiates enter the main room, hence it has a march-like tempo. What is noticeable in this and other Candomblé rhythmic patterns is the predominance of compound duple meters, 6/8 or 12/8, which allow for easy changes between duple and triple accentuations (either two times three–with accents on one and four–or three times two, with accents on one, three, and five). These rhythmic patterns are repeated several times in ostinato, and feel like a round rhythmic line that never ends. You can play this easily by tapping on a table, one beat on each hand, counting until six, and accentuating the right hand on one and the left hand on the four and then repeating it incessantly; then do the same, but this time accentuating the right hand on one, three, and five. Then you can simply alternate these accentuations repeatedly. A continuous circular feel emerges, and it is the insistence on these particular rhythmic patterns that helps create the trance among the Candomblé initiates. Also quite common is the distribution of five beats within a measure, so that the first three follow a triple division, while the last two follow a duple division. This five-note sequence played by the Rum and the agogô in the notated example below is very similar to some African time-lines and to Afro-Cuban claves (see Chapter 10).

It is believed that about 1.5 million Brazilians are devoted to the Candomblé religion and its practice is well known and acknowledged today. But this was not always the case. In fact, until the beginning of the 20th century Afro-Brazilians were prohibited from practicing their faith in the open. As a result, Candomblé worshipers often disguised the practice of their religion by blending it with Catholicism. In this way, many orixá names have come to be associated with catholic saints so that, for example, Yemanjá is also worshiped in Brazil as the Virgin Mary. Nonetheless, African songs and drumming remain the most important symbols of Candomblé and a strong mark of the African traditions preserved in Brazilian music. Even when it mixes with other traditions, crosses over to the secular realm, and is performed in commercial popular musics, African drumming has never lost its symbolic power of “communicating” with the supernatural and of linking Brazilians with their sacred African heritages.

Among the most popular Afro-Brazilian secular musical practices is the performance of capoeira, a fight/game/dance with movements similar to martial arts. During the times of slavery capoeira served to conceal fights among African groups and factions by disguising the fights as dances. Today it is used more as a dance and/or a game that also involves high degrees of physical strength and agility. Capoeira is performed by two players who dance in the middle of a circle made up of observers and other participants. What makes capoeira unique is the dependence of the movements on the music. Also noteworthy in the practice of capoeira is how it links Afro-Brazilians to other African derived traditions in the Americas. For example, the moves of capoeira closely resemble those of African American break dancing in the U.S.

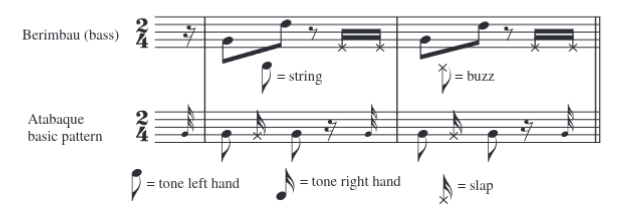

Capoeira’s toques (rhythmic patterns and tempo), dance moves, and style of fight are accompanied by one or more atabaques, pandeiros, and three berimbaus; the latter instruments give the music its most distinctive timbre. The berimbau is a musical bow made out of wood in the shape of an arc and strung with a steel wire and is played by striking the wire with a small stick. A dried gourd is attached at the bottom of the bow and serves as a resonator. Berimbau performers hold a small rattle, the caxixi, with the right hand and coordinate it with a rock or coin held between the thumb and indicator. When the rock or coin touches the wire, it produces the berimbau’s characteristic metallic, buzzing sound.

The capoeira dance/game is performed in a roda de capoeira (ring of capoeira) with three berimbaus of different sizes: the gunga, the bass berimbau, plays the melody and sets the rhythmic pattern and tempo that guides the choreography and style of dance. The other two are called berimbau medio and berimbau viola; they complement the gunga and improvise. Each berimbau produces two pitches, one low and the other one step higher. The different combinations of these pairs of sounds, the buzzing tone created by touching the string with the rock or coin, and the varying tempos make each capoeira toque distinctive.

While the dancers perform in the ring of capoeira, the participants continuously clap and sing in responsorial style, where the player of the berimbau gunga makes the call and the rest of the participants respond with small phrases in unison. A varied repertory of capoeira songs are learned orally, and have lyrics that report, revive, and recount the experiences of Afro-Brazilians since the times of slavery. In the roda de capoeira, the leader (gunga player) sings the ladainha, a long, narrative song, and then follows with a chula, which is sung in responsorial style…

Capoeira as a fight once served well in the slave’s fight for freedom. And it evidently received much disapproval from the ruling classes, who historically responded to capoeira gatherings with force and imprisonment. Although this is no longer the case and capoeira groups abound in all sorts of informal gatherings throughout Brazil, to this day the idea of resistance and liberation is ingrained in the minds of capoeiristas, regardless of their ethnicity or origin. Today, people from all over the world engage in capoeira for both its physical and spiritual benefits. Expectedly, there are countless capoeira academies spread across continents, and several international competitions with participants from all over the world, which are also readily accessible for viewing and listening through social media.

Back in Brazil, let’s look at how these Afro-Brazilian traditions merged with European styles and other traditions of the African diaspora in the Americas. The celebration of carnival is perhaps one of the best examples of how the mingling of these traditions in Brazil produced a unique musical style that was also able to cross the boundaries between traditional and popular musics.

Carnival is not unique to Brazil, but an ongoing tradition in various countries of the Americas where the Catholic Church played a role in colonization. Latin Americans from Cuba, Colombia, Mexico, Trinidad and Tobago, Argentina, and several other countries organize elaborate carnivals every year. The best-known North American equivalent is New Orleans’ Mardi Gras celebration. Originally a Roman Catholic annual event, carnival marks the preparation for the season of Lent, a period of fasting and disregard for the pleasures of the flesh (“carnevale”), which starts on Ash Wednesday, forty days before Easter. During the week leading up to the beginning of Lent, usually at the end of February, communities revel in the last opportunity for the excesses of the flesh and commemorate with masquerade balls, games, outdoor parades, musical performances, singing, and dancing. Carnival became especially important in Latin America in colonial days because servants and slaves were allowed to celebrate at the same time as, and even together with, the European colonizers and white elite. It did not take long for the celebration of carnival to become a symbolic act of inclusion, a time of collective euphoria when racial and social divides were replaced by celebrations of ethnic amalgamation, solidarity, and union.

Carnival is one of Brazil’s most widely shared cultural traditions. No other cultural expression achieves, so well and so intensely, the status of a “national” event. However, not everyone celebrates the same way. Brazilian carnival occurs in various formats, from small, rural, informal gatherings, to larger, urban, organized events. During the 19th century, carnival was celebrated in large cities with masquerade balls where dancers, in truly European fashion, danced waltzes and polkas until the crack of dawn. Old-time Portuguese traditions were also part of informal outdoor celebrations, such as the entrudo game, in which participants with painted faces danced and sung aimlessly in the streets while throwing powder and liquids at each other. Outdoor carnival celebrations became more elaborate in the first part of the 20th century, especially in large cities such as Rio de Janeiro, Salvador, and Recife where, to this day, parades including music, singing, and dance mark the event in an exquisite manner.

Rio de Janeiro hosts Brazil’s most elaborate carnival parade, one that has been considered the world’s most luxurious outdoor celebration. Since early in the 20th century, small neighborhood groups called blocos and cordões have paraded in Rio de Janeiro’s streets during carnival in costumes, singing and dancing popular tunes accompanied by brass instruments and zabumbas. But it was the participation of Afro-Brazilians in these outdoor celebrations that transformed an essentially European tradition into a Brazilian celebration. In less privileged Rio de Janeiro neighborhoods, where the population consisted of low-income European immigrants and a majority of mulattoes and Afro-Brazilians, carnival was celebrated with African derived dances, such as batuques, lundus, and later sambas, accompanied by percussion.

Samba music and dance have origins in the Angolan semba, and are found to this day in their original form in rural areas of Brazil. Samba involves a specific choreography, the umbigada, in which dancers move their navels and hips inviting others to dance. As Afro-Brazilians migrated from Bahia to Rio de Janeiro, they brought samba with them and in the new urban context it was mixed with European dances such as the polka and the march to become the urban version of samba performed during carnival. Since the 1930s, samba music and dance have become the hallmark of Rio de Janeiro’s carnival parade, with its marching and percussive music and a choreography that still recalls the traditional umbigada.

As outdoor carnival parades became more elaborate, people started to meet to rehearse their sambas. These meetings, called escolas de samba, samba-schools, were transformed into neighborhood associations, where participants could meet and learn to perform, sing, and dance that year’s samba and to learn their role in the parade. The first school of samba Deixa-Falar started the tradition in 1928, and by the 1930s, several samba-schools were parading in the streets of Rio de Janeiro in fierce competitions. With subsequent state supervision and financial support, Rio de Janeiro’s samba-school parade has grown to gigantic proportions; it has become a multi-million-dollar industry and a showcase for tourists. In 1984, Rio de Janeiro’s government built the sambódromo, a mile-long street with bleachers on either side with a capacity of some 65,000 spectators. Today, some 60 samba-schools with some 2,000 to 4,000 dancers each parade to samba music and dance during carnival with luxurious costumes and floats. But despite the current carnival’s grandeur, samba schools are still local entities headquartered in the neighborhoods where the schools’ participants live. The success of the parade depends on a large population of low-income and mostly mulatto and Afro-Brazilians who work throughout the year as a community for their samba school to have a one-day magnificent carnival show.

Every year, the organization of the parade involves:

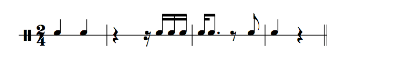

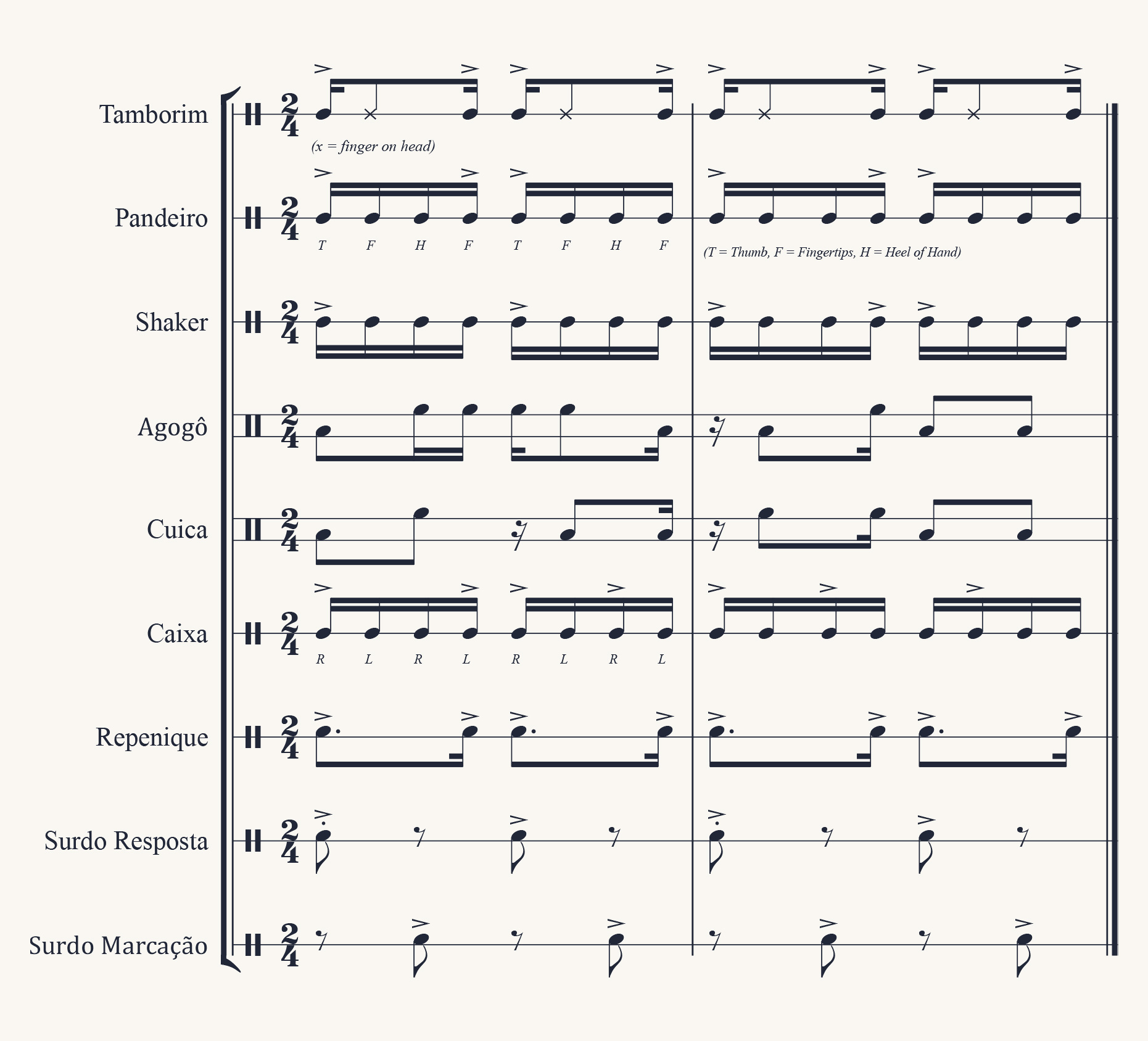

Schools of samba parade with a style of samba called samba-enredo (samba-plot), strophic songs that narrate a story related to the experience of Brazilians, usually a historical event. This enredo (plot) is then dramatized in the parade with music and dance, in the traditional Iberian style of dramatic dances that can also be viewed as a popular, outdoor opera. Unlike traditional dramatic dances or opera, samba-enredos are seasonal compositions: a new one is needed every year for the parade. Like commercial popular musics, sambas-enredo have catchy, memorable refrains that can be easily learned by large numbers of people whose enthusiastic singing helps their neighborhood do well in the competition. To coordinate a large group to sing together over a one-mile stretch of street, a leader, or puxador, sings from a strategic position or with a microphone, and accompanies himself with a cavaquinho, the same ukulele-like four-string instrument we encountered in the dramatic dance Folia de Reis. As with other types of sambas, samba-enredos are duple meter march-like songs that help dancers make their way through the sambódromo in synchronization. The singers and dancers are accompanied by a huge percussion section of some 300-500 performers called the bateria. Samba baterias include a variety of instruments from both European and African heritages. The most important instruments in samba-schools’ baterias are:

1) Surdo: a bass drum played with one mallet while damping the head with the other hand. The surdo provides the basic duple-meter rhythm that drives the samba. There are three kinds of surdos: the one with the largest and deepest sound is the surdo marcação. It accents the “2” of the basic “1, 2” rhythm of samba, while the surdo resposta (response) answers accenting the “1”. The smallest surdo is the cortador fills in with syncopations.

2) Repique: a high-pitched double-headed drum played with one hand and a small mallet. The repenique plays the part of a conductor for the bateria; it supports the surdo beats and provides the calls that cue the entrances of the other percussionists.

3) Cuica: a friction drum. The cuica is a single-headed drum capable of producing both high and low pitched notes that are essentially improvised on top of the basic surdo marching beats. The cuica’s “squeaking” sound is produced by rubbing a damp cloth along the stick inside the drum with one hand (see picture below). The thumb of the other hand is used to press down on the skin of the drum to produce different pitches, usually a combination of high and low.

4) Caixa or tarol: a double-headed snare drum played with two sticks.

5) Pandeiro: a hand held, single-headed frame drum similar to a tambourine with metal jingles and a tunable head. The pandeiro produces different sounds when it is played with the thumb, fingertips, or palm of the hand. It is in a variety of types of sambas and related musical styles and genres. We already discussed its use in dramatic dances and will see it again in bossa nova (below). In samba-schools, pandeiro performers show off their dexterity by tossing the instrument around with acrobatic movements while they parade (see picture above).

6) Tamborim: the smallest and the highest pitched drum in the bateria; the tamborim is a single-headed small frame drum and it is played with a flexible metal drumstick and has no jingles. Tamborims provide countermelodies or polyphonic improvisations on top of the constant syncopated rhythms of the lower drums.

7) Agogô: a double (or sometimes triple) bell of African heritage. It provides a metallic sound and melodic quality to samba percussion, and alternates between high and low pitches. We already encountered agogôs in the percussion group that performs in Candomblé rituals.

8) Ganzá our chocalho a shaker. Ganzás come in a variety of shapes and styles, but modern ones are constructed from several metal canisters filled with beads and attached to one another to produce a loud sound.

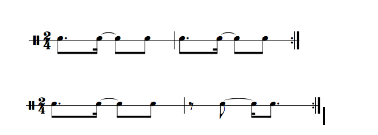

Each of these instruments plays a short rhythmic ostinato, which can be repeated incessantly or varied according to the skills of the performer and the role of the instrument within the bateria. Below you can see a few of these rhythmic patterns, but keep in mind that an infinite number of variations are possible. The score shows two measures that can be repeated continuously. What is important to note are the polyrhythms and the dense texture produced by different timbres in the percussion and the variations in each instrument’s rhythmic patterns.

Keep in mind that it is a huge challenge to put together a winning parade with impeccable bateria, singers, dancers, costumes, etc. The largest samba-schools in Rio de Janeiro have web sites with video, pictures, and descriptions of the entire process. Check out the sites for Rio de Janeiro’s most traditional schools of samba: Mangueira and Portela. Although the sites are in Portuguese, on their pages you can hear all their sambas-enredos, including the latest one in preparation for the next carnival celebration.

In the Northeast, very distinctive carnival celebrations showcase Brazilian cultural richness. In the 1970s and 1980s carnival in the city of Salvador (state of Bahia) became an important channel for the expression of Afro-Brazilian traditions and for the unification of African cultures in the diaspora. Less formal than the samba-school parades in Rio, in Salvador blocos (groups) gather thousands of participants to parade around town for a week (sometimes longer) before Ash Wednesday. The most traditional groups are the Afoxes, who celebrate their authentic African roots by bringing to the streets instruments and rhythms used in Candomblé. Another typical group is the bloco-Afro, who parade to the sounds of Afro-Brazilian songs and percussion, but also include Afro-Caribbean rhythms and instrumentation. The best-known bloco-Afro in the 1980s, Olodum, has performed with a variety of mixed Afro-Brazilian and Afro-Caribbean rhythms, like the samba-reggae, which weds Candomblé, samba, reggae, and merengue rhythms and instrumentation. Their ensemble includes surdos, repeniques, and caixas, as well as congas and timbales. Recently Olodum has added saxophone, electrical guitar, and keyboard to the band to attract a pop international audience. In 1995, they recorded in Salvador with Michael Jackson the song “They don’t care about us,” and performed several times outside Brazil with well-known artists. In 2014, they provided the instrumental accompaniment for Pitbull and Jennifer Lopez in the official song of the World Cup, “We are one, Ole, Ola.”

Yet another way carnival is celebrated in Salvador is with the Trio Elétricos. These are huge trucks onto which all manner of electronic instrumentation is mounted to offer loud music to throngs of up to 20,000 people who follow dancing through the city’s streets. Active since the 1970s, Trio Elétricos have become fantastic machines of sound and light. To give you an idea, each of these trucks is equipped with guitars, bass, several keyboards, electronic and traditional drums, and up to 68 amplifiers, each one producing 650 watts of sound that feed some 206 loudspeakers.

In the1990s, the new electrified carnival of Salvador gave rise to Axé music. Axé is a Yoruba word that can be roughly translated as “good vibrations” or “power.” In music, Axé is an umbrella term used to refer to dance-like music that mixes Afro-Brazilian (Candomblé and samba) and Afro-Caribbean musics (reggae, merengue, rumba), with the electric sounds of the Trio Eletricos and disco. Axé tunes have crossed boundaries to become major hits in Brazilian commercial popular music, as well as best sellers in the market for “World Music.” One of the pioneers of Axé music is Daniela Mercury , a versatile songwriter, arranger, and energetic performer, whose career as a singer has grown to impact the music scene in Brazil and abroad.

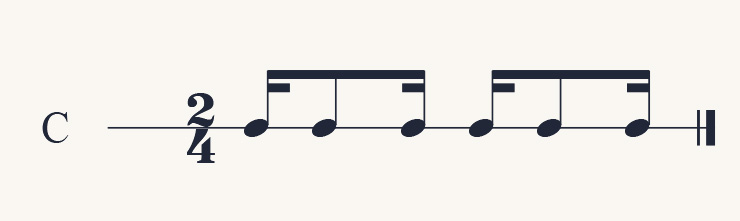

Before the emergence of the recording industry, radio, and the movies early in the 20th century, theaters and dance halls were the main venues for the popularization of music in urban areas of Latin America. Quite popular in Brazil were arrangements for small ensembles of operatic arias, short songs in Portuguese called modinhas, and European dances, in particular polkas, marches, and waltzes. The polka was the most popular dance and, just like rock and roll in the middle of the 20th century, it spawned a variety of local variants throughout the Americas; these include the Brazilian fado, the Brazilian tango, the habanera (from Havana, Cuba), the two-step and ragtime (from the U.S.), and several others. At times, these dances, regardless of their titles, were nothing but polkas written for the growing white middle class. But overall, the New World versions shared one common trait: the lively duple meter of the polka was wedded to rhythmic figures derived from theatrical renditions of African derived dances. Invariably they included syncopations and/or dotted rhythms in the bass, the melody, or both; they also tended to stress off-beats and favor anacrusis. Some of these rhythms are notated in the musical example below.

In Rio de Janeiro the most popular of these polka-derived pieces was the maxixe. Born in the poor neighborhoods of Rio de Janeiro where Afro-Brazilians, Portuguese, and other immigrants lived in close proximity in small tenements, the maxixe was first popularized in comic theatrical acts.. The maxixe was a couple-dance in duple meter, with syncopation and dotted rhythms in the bass line, and short melodic lines that usually started on the upbeat. These generic characteristics were not unique to the maxixe, as mentioned above. What made the dance so popular at the time was not the music per se, but a daring choreography saturated with sexual overtones that involved female and male hip movements in close contact.

At the turn of the 20th century, the most successful Brazilian composer of polkas, waltzes, tangos, and maxixes was Ernesto Nazareth (1863-1934), who became known as the “king of the Brazilian tango.” Nazareth was also a virtuoso pianist who made a living playing in cafés, theatrical intermissions, and in early movie theaters. He was one of those musicians who, like U.S. composer and pianist Scott Joplin, filled the needs of the early music industry at a time when the distinctions between popular music, mass culture, and concert music were not yet clearly defined. Thus, his pieces were performed in the streets and cafés, as well in concert halls; they were recorded on piano rolls and were among the earliest pieces recorded by Casa Edison (Odeon), the first Brazilian recording company.

Waltzes, polkas, Brazilian tangos, maxixes, and habaneras circulated in sheet music publications for the piano, but they were also performed in the streets of Rio de Janeiro by popular musicians in instrumental ensembles composed of flutes, trumpets, trombones, and other instruments common in military bands, dance and theatrical orchestras. Soon the ensembles incorporated guitars, mandolin, and cavaquinho. The performers in these ensembles became known as the chorões, probably because of their overuse of low guitar notes as countermelodies to their improvised elaborations on long melodies, a style that was described as chorar, to lament or cry, although the origin of the word is still a controversy among scholars. Chorões improvised on modinhas, arias, polkas, waltzes, habaneras, tangos, and maxixes, bringing several urban musical experiences together and integrating the European and African heritages in the Brazilian context. The music performed by the chorões eventually became known as choro (cry or lament), or chorinho, Rio de Janeiro’s first style of instrumental popular music.

In choro, long melodies reminiscent of operatic arias are extended in improvised instrumental passages. The mandolin, cavaquinho, and flute are the preferred soloists and have roles similar to that of an operatic “prima donna.” But the ensemble may also include a piano, a clarinet, and light percussion used to stress the syncopated rhythms popular in Brazilian tangos and maxixes. A famous musician who made significant contributions to the choro repertory was Alfredo da Rocha Viana Filho (1896-1973), an Afro-Brazilian performer (flute and saxophone), composer, and arranger known in Brazil as Pixinguinha. He left a long list of pieces that have become standards in the repertory of Brazilian popular music. In the 1920s, he traveled to Europe with his group, Os Oito Batutas (The eight masters), where they showcased their skills in instrumental improvisations. In several ways, Pixinguinha and his group’s role in the Brazilian popular musical scene of his time parallel that of African American composer and band leader James Reese Europe, who also visited Europe with his ensemble during WWI and introduced jazz abroad.

Maxixe, tango, and choro could not have developed as powerful creative musical styles, as a combination of European melodies and dances, and African-derived rhythms and choreographies, if it was not for the marked presence of Francisca Gonzaga (1947-1935). A woman working in a male-dominated world, she managed to contribute to the development of early popular music industry in Brazil in a number of ways, as a composer, performer, ensemble director and manager, as a collaborator with the most prestigious musicians of her time, and as a defender of the rights of the popular musician. She left a long list of works that are the definers of the early popular musical styles in Brazil. She wrote works for the dance hall, waltzes and polkas, as well as for the theater where she experimented with the myriads of rhythms being introduced to audiences on the city’s stages. Listen, for example, to her “Pudesse esta paixão”, and “Corta Jaca”, where she uses the dotted rhythms of tangos and maxixes to support long melodic lines that recalls Italian opera, a coexistence of styles so characteristic of the time and of which she helped shape and develop in creative ways.

Choro music was kept alive throughout the 20th century thanks to the performances of virtuosos such as mandolin master Jacob do Bandolim (1918-1969) and cavaquinho virtuoso Waldir de Azevedo (1923-1980). As a result of their revival efforts, choro is taught today in music schools, where young performers learn the art of instrumental improvisation and virtuoso performance and preserve this Rio de Janeiro tradition.

In the 1930s and 1940s another popular musical style dominated the recording industry and radio: the samba-canção (samba-song). We already learned about samba-enredo performed during carnival in Rio de Janeiro. In samba-canção, however, samba’s danceable, syncopated rhythms are softened by slower tempos, long melodies, and romantic lyrics. Rather than full-scale percussion ensembles, samba-canção favors the guitar and light percussion, and occasional accompanying flutes, brass, or string orchestra. A prominent role is given to the solo singer; thus, samba-song crooners became national radio stars during the 1930s and 1940s. The earliest example of a recorded samba was the 1916 song “Pelo telefone” by Donga and Mauro de Almeida, but it took until the 1930s for samba songs to impact the national scene. One of the most successful samba singers/composers was Noel Rosa (1910-1937). During his short lifetime, Rosa wrote memorable sambas with sophisticated lyrics and well-crafted melodies that appealed to a large middle-class. His sambas, now classics in the repertory of Brazilian popular music, created a tradition in Brazilian popular song that influenced later styles such as Bossa Nova and MPB.

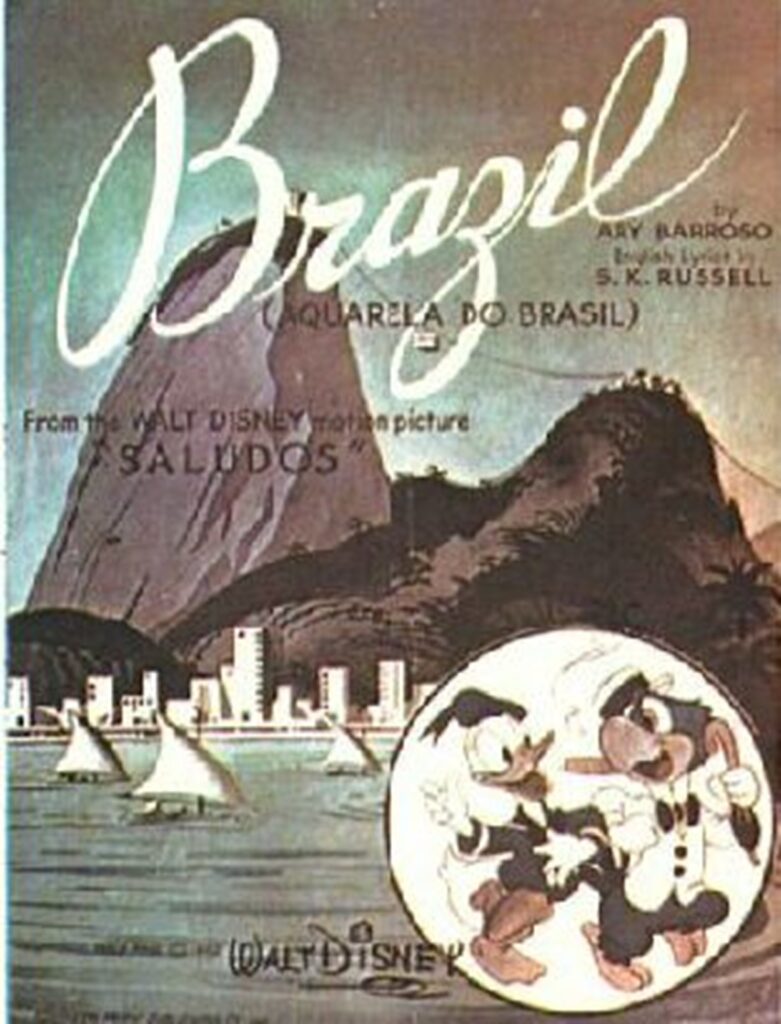

Another important samba-canção composer was Ary Caarl(1903-1964), the author of the famous “Aquarela do Brasil” (1939) (known in the U.S. simply as “Brazil”). The song is in a style called samba-exaltação, a samba-song with nationalistic lyrics that praise the beauty of the country and its people. “Aquarela” and other similar sambas were important tools for political propaganda during the populist government of Getulio Vargas. “Aquarela” also boosted Barroso’s international career when it was included in Walt Disney’s movie Saludos Amigos (1942). Since then, the song has been recorded with English and Portuguese lyrics in a variety of arrangements by famous artists like Frank Sinatra, Johnny Mathis, Dezi Arnez, Dionne Warwick, Ray Conniff, and Chick Corea, among others. One of the most popular interpreters of Barroso’s sambas was Carmen Miranda, whose voice, dazzling performing style, and outfit recalling Afro-Brazilian Candomblé dancers showcased samba-songs as an international symbol of Brazilian music (see Chapter 10).

The popularity of samba in its various formats has never slackened. A more recent style called samba-pagode has taken the lead in popularity as a way of going back to samba’s roots and shying away from the largely commercialized carnival sambas. Samba-pagode is most prevalent in large Brazilian cities and is usually performed in social gatherings and bars. It features a singer soloist and a small instrumental ensemble consisting of cavaquinho, pandeiro, shakers, tamborim, a repique de mão (a one-headed drum placed on the performer’s lap and played with hands), and a tan-tan (a portable bass drum played with hands).

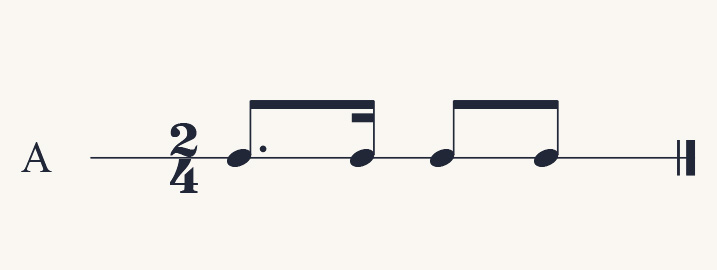

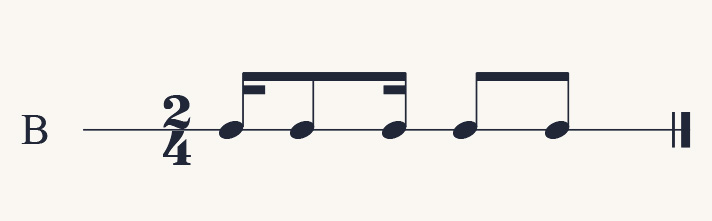

In the 1960s and 1970s, Brazilian urban popular music was greatly diversified as a result of industrial development and the empowerment of the middle and upper classes. Bossa nova (new wave or new style) led the way. The “new” style was associated specifically with the city of Rio de Janeiro and the lifestyle of its classy neighborhoods, dreamlike beaches, blue summer skies, and easy upper-class life. Singing in an intimate low tone and using the picking of guitar chords to emulate samba percussion, singer/composer João Gilberto (1931-2019) started the trend. Gilberto was joined by highly educated and extremely creative musicians and poets, such as composer Antônio (Tom) Carlos Jobim (1927-1994) and poet Vinicius de Moraes (1913-1980). Together they wedded long melodic lines derived from 19th century operatic bel canto with the popular guitar of the chorões, the percussion beats of samba, and their original, well-crafted lyrics, creating a “new way” of performing samba-canção. Gilberto and Jobim then updated the samba-canção with new arrangements and instrumentation; similar to samba songs, in bossa nova only light percussion is featured, usually the pandeiro and a shaker. But then, they brought the guitar to the forefront and used it to recreate the samba syncopations with a characteristic bossa nova beat (see the musical example below). Bossa Nova musicians also added jazz harmonies to their songs. Jobim’s songs are saturated with 9th and 11th notes piling on chords that move in parallel motion, a common characteristic of jazz. In addition, influenced by his classical music training, Jobim’s long melodic lines move easily and smoothly in the most awkward directions (as in the song “Wave”), or do not move at all (as in the song “One note samba”), but are supported by fast changing harmonies in the bass, recalling the guitar of the chorões. These elements made the music extremely attractive to cosmopolitan audiences in Brazil, the U.S., and Europe. Jobim’s tunes became classics in the pop music world and are alive today in the repertory of jazz musicians in Brazil and abroad. The intimate, laid back feel of bossa nova has also made it appealing as background music in cocktail parties, waiting rooms, and elevators.

Soon after Bossa Nova reached the international music scene, a political turmoil erupted in Brazil; the years between 1964 and 1985 mark the emergence and fall of a military regime. During this time, the country witnessed another wave of nationalism, a movement led by left wing intellectuals, artists, and musicians, who presented themselves as both critics of the regime and defenders of an authentic Brazilian music. This new, politically oriented musical movement promoted a variety of styles that were grouped under the umbrella term MPB, an acronym for Música Popular Brasileira (Brazilian Popular Music). As with Bossa Nova, MPB musicians were highly educated, middle-to-upper-class artists who catered to the tastes of left-wing intellectuals and college students. But instead of bossa nova’s jazz harmonies and laid-back soft lyrics dealing with beaches and easy life, in MPB the focus was on socio-political lyrics and stylized versions of Brazilian traditional musical styles.

The most well-known MPB musician is Francisco Buarque de Hollanda, known as Chico Buarque (b. 1944). Born into a family of intellectuals and writers, Chico Buarque’s music and lyrics reflect both his opposition to the military dictatorship and his criticism of the social and racial issues affecting the country. In 1971 he released the LP Construção (Construction). The title song of the album, “Construção,” shows how Chico Buarque puts his musical and poetic talent to work for socio-political criticism. The lyrics are a long narrative on the tragic death of a construction worker during a morning of heavy traffic on a busy street. Chico Buarque’s lyrics are filled with double-entendres and build the story slowly and in layers, to convey the emptiness and lack of prospects for uneducated workers in urban Brazil. As with his ingenious play of words, Chico Buarque’s music helps to “construct” the story with a clever use of instrumentation. The work starts only with voice and percussion and has the feel of an old-time samba. But as the story unfolds new instruments are added to intensify the dramatic plot. A full brass section enters as a surprise in the last sentence, to overstress the worker’s death.