In the twenty-first century, one may hear something called “Andean music” nearly anywhere in the world. For decades, musicians playing stylized versions of indigenous Andean music have populated the subway stops and festival stages of major cities throughout Europe, Asia, and the Americas. Instruments once tied to distinct indigenous communities and seasonal practices in the Andes––such as panpipes or the charango, a small stringed instrument similar to a tiny guitar––can now be heard on Hollywood movie soundtracks, sampled into popular rock and rap hits, and found for sale at import shops and online music stores in the United States. More often than not, such music is accompanied by images of llamas and towering mountains, or the Inca ruins at Machu Picchu, linking ideas about Andean music with rural indigenous lifeways and the ancient past in the global imagination.

This sort of music represents only a small and relatively recent part of the extraordinary musical and cultural diversity of the Andean region. For nearly five centuries, the Andes have been a site of significant cultural mixing between indigenous, Spanish, and African peoples. This mixture, or mestizaje, however, is distinctive from that of many other areas in Latin America, due in part to the enduring and vibrant legacy of the region’s indigenous heritage. Quechua– and Aymara-speaking peoples, two of the largest indigenous linguistic groups in Latin America, have constituted an outright majority of the population in the countries of Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia throughou much of their history, and more than ten million people continue to speak these languages daily. To the east, in the upper reaches of the Amazon basin, and stretching south to the Patagonian region, dozens of other distinct indigenous groups preserve their own languages and cultures. These groups have rarely held significant political or economic power in the region since the Spanish conquest, but their large numbers have nonetheless made them a dominant flavor in the cultural stew of Andean societies.

Urbanization, emigration, and the transnational media also play an important role in the formation of contemporary Andean musical cultures. The last half century has witnessed a tremendous demographic shift as people in rural areas have left their villages and resettled in larger cities in search of work and opportunity. A majority of the Andean population today is thus more likely to live within sight of a skyscraper than a snow-capped peak—or, in some places, both simultaneously. Whether urban or rural, most residents of the Andes now dress in Western clothing, watch television, and own cellphones, and many use the Internet daily for communication and commerce. Not surprisingly, these developments have further diversified musical practices. Young people especially find new ways of expressing their identities, fusing indigenous, mestizo, and Afro-descendant traditions with rock, rap, and other Latin American popular musics, even as those traditional forms continue to be valued and performed on their own. Indeed, one of the striking features of musical traditions in the Andes is that nothing ever seems to be abandoned completely; newer forms exist alongside older ones, all changing and evolving together, in a process of continual layering.

The very diversity of peoples and cultures in the Andes makes defining the region, musically or otherwise, difficult. Geography has played an important role in creating this diversity. The Andes Mountains, with their endless deep valleys, high plateaus, and snow-capped peaks and volcanoes, stretching for thousands of miles along the western edge of South America, constitute an imposing barrier to the movement of people and goods, and many cultural microregions have consequently emerged within this rugged landscape. On the Andes’s northeastern flanks lie the equally forbidding rainforests of the Amazon basin, while to the west, the mountains descend to a narrow strip of coastal land along the Pacific Ocean, marked by dense vegetation and rainforest in contemporary Ecuador and Colombia to the north and stark desert in Peru and northern Chile in the south. This coastal region is where many of the largest cities are located, and in Peru, it is now home to a majority of the country’s population.

Numerous civilizations have united broad stretches of the Andean region over the last five thousand years. Of all of the empires to emerge prior to the arrival of the Spanish, however, none compared in size or power to the Incas. Centered in Cuzco, the Incas grew from a small regional state in the fourteenth century to a massive empire a century later, dominating an area that stretched from northern Ecuador to central Chile. Known in Quechua as Tawantinsuyo (“Four Suyos,” representing the quartal division of the empire), the rapid expansion of the empire was facilitated by an innovative blend of military ruthlessness and cultural flexibility. Although the Incas forcibly resettled those who resisted their control, they also demonstrated remarkable tolerance to certain cultural and religious differences among their subjects. Consequently, though Quechua was imposed as the official language of the realm, musical practices varied widely, which helps to explain some of the continued musical diversity found in the region.

The arrival in 1532 of Francisco Pizarro and his Spanish conquistadores to the shores of Peru signaled an abrupt end to Inca rule. Aided by lingering resentment of Inca control among some conquered subjects, the Spanish rout of the empire was as quick as it was devastating. Within a few short decades following Pizarro’s execution of Atahualpa, the last Inca emperor, the Spanish had built a new colonial regime literally on the ruins of the one it defeated. Spaniards made use of the roads and other aspects of Inca infrastructure to quickly establish their control and authority over the region, and constructed new Christian churches and cathedrals directly on top of sacked Inca temples (Figure 8.2). The Spanish colony also built upon Incan or otherwise indigenous cultural practices. The forced conversion of Andean peoples to Christianity, for instance, was often accomplished by inserting Catholic elements into pre-existing indigenous festivals, and many religious and musical practices retain an essentially hybrid character today.

European colonization also ushered in a new period of racial and ethnic differentiation in the Andes. Early mixing between indigenous and Spanish populations produced a substantial class of mestizos, who formed an important intermediate social class between elites and peasants. The Spanish also introduced enslaved Africans to the Andes in the sixteenth century. Though Afro-descendant peoples make up only a small percentage of the current Andean population, they constituted a sizable presence during the colonial era, outnumbering Europeans in some areas, and they strongly impacted the region’s music. Afro-Andeans also intermarried with the local indigenous population, producing yet another racial category: zambos, people with combined Indigenous and African ancestry.

Over time, these terms came to describe social position more than biological heritage, and by extension, a set of cultural practices that included music. After independence from Spain in the early 1820s, for instance, criollos—descendants of Spanish settlers—took over from Spaniards at the top of the social order. Though the term criollo maintained an implicit association with lighter skin, in practice it referred to any member of the elite class with a European cultural orientation. Similarly, by the nineteenth century, most people identified as indio (“Indian”) or mestizo could likely trace their background to both indigenous and Spanish forebears; individuals were identified as one or the other based less on physical appearance than on where they lived, their social position, and their cultural practices. The growing presence of other ethnic groups in the later nineteenth century, including small but significant populations of Japanese, Chinese, and Arab immigrants to certain Andean regions, and their consequent intermarriage with local mestizos and others, only reinforced the social (as opposed to strictly racial) nature of these identities.

In the twentieth century, a number of political, economic, and social forces combined to further diversify local identities. As already noted, massive migration from rural to urban areas at mid-century produced a new class of urbanized indigenous people, often referred to derisively as cholos, even as efforts to combat the discrimination faced by the indigenous population surged. Progressive and populist governments in Peru and Bolivia sought to valorize the contributions of indigenous cultures to national identity, while simultaneously emphasizing class over ethnicity in official discourse, for instance replacing the derogatory term indio with campesino (“peasant”) in Peru. Indigenous peoples themselves also took the lead in asserting their rights in the latter twentieth century, particularly in Ecuador and Bolivia, where social movements of indígenas— their preferred term—have become a powerful political force.

This chapter explores some of the musical practices of the people who inhabit and define the social and cultural landscape of the contemporary Andes. It focuses particularly on Peru, the largest and arguably most diverse of the central Andean countries. With a population of 34 million people, divided between the cosmopolitan cities of the coast, the smaller villages and towns located in the Andes mountains themselves, and the vast expanses of the upper Amazon, Peru provides a reasonable cross section, both geographically and culturally, of the Andean region as a whole. The first section surveys a broad range of folk and popular music, beginning with Indigenous genres deeply rooted in the colonial and pre-Hispanic past, proceeding through mestizo and criollo practices, and ending with an examination of popular music genres of more recent, cosmopolitan derivation. The chapter concludes by considering the history of art music in the Andes since the nineteenth century.

Indigenous Musical Practices

Andean Indigenous peoples have hardly lived “outside” of history; the forces of colonial and postcolonial rule have had a tremendous impact on their social and political organization and are reflected in many of their most important cultural and religious practices, from festivals celebrating Catholic saints to the adoption of European instruments, like the harp and violin. Nonetheless, Indigenous peoples continue to hold on to many spiritual, ritual, and musical practices whose roots date to the precolonial era. Certain instruments, such as panpipes or the end-blown kena flute, have had a continuous existence in the Andean region for millennia. Other ideas about music also clearly predate the arrival of the Spanish, including a widespread preference for dense, high-pitched sounds and the use of paired musical structures.

Taken as a whole, indigenous musical practices vary tremendously. In some places, a walk of an hour from one village to another may present a listener with an entirely different set of instruments, genres, and musical or ritual events. Certain instruments and practices, however, are associated with broader regions. The latter is true of the two contrasting examples focused on here: the singing of songs called harawis in a Quechua-speaking village in Ayacucho, a region in south-central Peru, and the playing of panpipes called sikus in the area surrounding Lake Titicaca, along the Peruvian/Bolivian border.

The Harawi

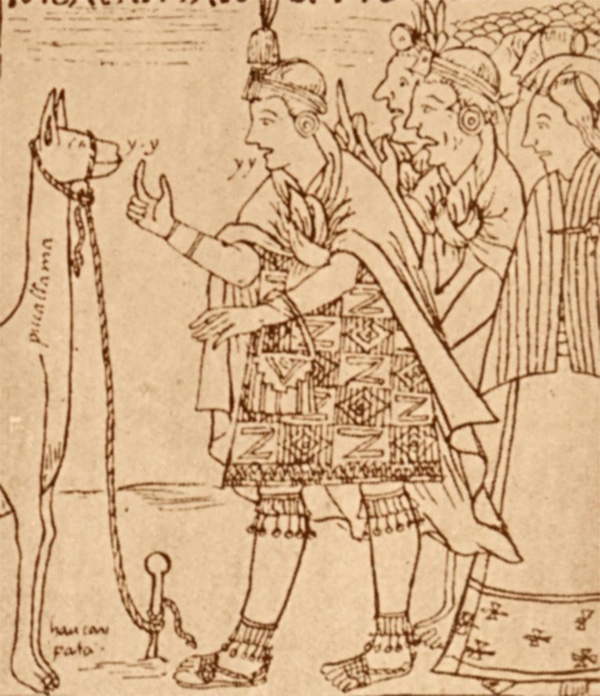

The harawi is one of the oldest musical forms practiced in the Andes, a vocal genre dating to the period of Inca rule. According to early Spanish chroniclers, the Incas sang harawis on many occasions: during the harvest season, as love songs, and as epic sung poetry performed at Inca festivals (see Figure 8.3). Unfortunately, the chronicles provide few clues about what such songs actually sounded like. We do know that the meanings and performance practice of the genre evolved over the intervening centuries. Harawis today are sung in Quechua-speaking communities primarily to accompany agricultural work or for ritual occasions, such as the roofing of a house or the burial of a deceased infant.

Musically, perhaps due to their roots in the pre-Hispanic era, harawis are distinctive even in comparison with other kinds of indigenous Andean music. Sung a cappella, they are performed exclusively by older women in a high vocal range, and are often limited to a three-note or tritonic scale. Though residents of small villages in the Andes are increasingly bilingual, harawis are still sung exclusively in the Quechua language, with lyrics derived from long-standing oral tradition. Verses are usually repeated, and lyrics alternate with vocables (syllables like “la-la-la”). The latter are especially prominent at phrase endings, when the women sing a high “ay yah!” or “yaooh!,” then let the melody slide down in a long glissando—one of the defining characteristics of the genre. The performers include any capable female singers who happen to be present; harawis thus often have a heterophonic texture, with each woman varying her melody slightly in accordance with her own preferences and knowledge of the song. This type of slightly varied repetition, in which a single musical phrase is performed repeatedly with minor variations, is typical of indigenous Andean music.

Listening Guide 8.1, a harawi, was recorded in the village of Alcamenca, a small town in the Ayacucho region, at the beginning of a long day of work planting corn. Periodically throughout the year, members of the community come together for faenas, or communal work parties, to clean an irrigation canal, fix a road, or in this case, plant a communally owned field. Work at the faena is usually separated by gender, with men working in the field, while women sing, prepare food, serve periodic glasses of chicha (homemade corn beer) or a handful of coca leaves to each worker, and in between these tasks, work in the field themselves.

In Alcamenca, agricultural harawis are sung at the beginning, middle, and end of the workday. On this occasion, as the men begin to work, the women gather in a corner of the field to perform the morning harawi, modestly placing their hands over their mouths and following the lead of the most experienced singer.

The harawi is the only genre performed in this region without instrumental accompaniment. During other times of the year, or at other musical or ritual events, one may hear harp and violin duos, brass bands, saxophone orchestras, cow-horn trumpet duos, six- or twelve-string guitars, and more––sometimes, during major festivals, all at once! As with most regions dominated by Quechua-speaking peoples, though, people in Alcamenca place heavy emphasis on vocal genres and songs. Even in the case of instrumental performances, the melodies played often come from songs with lyrics. Moving farther south to the Peruvian-Bolivian border, however, to the high arid plateau known as the altiplano, songs diminish in importance and purely instrumental genres come to the fore.

In depth

Numerous indigenous groups throughout lowland South America practice forms of shamanism, in which ritual specialists, often referred to as curanderos (“healers”), communicate with spirit and/or animal worlds for purposes of healing, prophecy, and more. Though found as far south as central Chile among the Mapuche people, shamanism is particularly prevalent among groups in the upper Amazon. In this region, bordering the eastern Andes, shamans play an important role in the ritual life of indigenous peoples such as the Shuar and Napo Runa in Ecuador and the Asháninka and Shipibo-Konima peoples in Peru.

Music forms a key part of shamanic practices, structuring phases of a ritual while acting as a bridge between human, spirit, and animal worlds. Among the Napo Runa, for example, shamans called yachaj (Quichua for “one who knows”) are believed to travel via song between this world and the spirit world in the context of healing ceremonies. In addition to providing a vehicle for metaphysical travel, songs offer commentary on the healing process itself, identifying sources of illness and narrating their resolution.

One Amazonian practice that has drawn global attention in recent years is the use of ayahuasca, a psychoactive tea brewed from the banisteriopsis caapi vine and other plants that produces strong visions and hallucinogenic effects among users. In ayahuasca ceremonies, typically lasting all night, a curandero uses music to create a structured and protected space for healing and transformation, guiding participants’ experiences and shaping the emotional and spiritual dimensions of their journey. The rhythms, melodies, and tonal qualities of the music can influence the flow of visions, emotions, and insights, helping participants navigate the often intense and unpredictable effects of the ayahuasca brew.

At the heart of this musical tradition are icaros, sacred songs sung by the curandero during the ceremony. Icaros are believed to carry spiritual power, transmitted through direct experience, dreams, or teachings from plant spirits. Each icaro has a specific function—it may call in protective forces, cleanse negative energies, summon healing spirits, or guide participants through difficult psychological territory. The curandero often tailors the choice and delivery of icaros in response to the energy of the group or the needs of individual participants, functioning as a spiritual navigator throughout the journey.

Beyond their energetic and spiritual influence, icaros serve as a bridge between the physical and non-physical realms. Their often repetitive, hypnotic nature can help induce altered states of consciousness, deepen introspection, and connect individuals with deeper layers of memory, emotion, or transpersonal awareness. For many, the music becomes the language through which healing and insight are transmitted, making it not just an accompaniment to the ceremony, but an integral and transformative part of the experience

Look for the CDs Music of the Jívaro of Ecuador (Folkways FE 4386, 1973), which includes several tracks recorded by a Shuar uwishin or shaman, and Soul Vine Shaman (Polar Fine Arts, 2007), featuring a field recording of an ayahuasca ceremony among the Napo Runa.

The Sikuri

The use of wind instruments (aerophones) has a long history in the Andes, with archeological remains of flutes dating back more than four thousand years. Indigenous communities of the altiplano still play dozens of different wind instruments, including tarkas (block duct-flutes), kenas (end-notch flutes), and perhaps most famously, different types and sizes of panpipes such as the siku (see Figure 8.4). While it is standard practice in Western societies to combine different types of instruments in a single ensemble—such as a saxophone, trumpet, piano, bass and drums in a small jazz group—most indigenous wind instruments are performed exclusively in groups of similar instruments, accompanied by drums or other percussion. This practice derives in part from the association made between certain instrument types and the season in which they are played. Panpipes are considered a “dry season” instrument, for instance, and many believe that playing them during the growing season could attract a drought or frost. Even in places where such beliefs no longer hold, dry season instruments are simply not played with their wet season counterparts.

Though all members of a siku ensemble may play the same instrument, they do not necessarily play the same part; this is a crucial component of the community-based nature of this music. Sikus are constructed in pairs, with the complete notes of a diatonic scale alternating between the two halves of the instrument (see Figure 8.5). A different musician plays each half in a practice of interlocking notes called hocketing. Though similar techniques existed in medieval and Renaissance Europe, evidence suggests that hocketing has been used in the Andes since at least the Inca era, and perhaps as far back as the Moche civilization (400–1000 CE). Hocketing requires a great deal of coordination between two mutually dependent players or groups of players, who play parts identified as ira and arca (“leader” and “follower,” respectively, in the Aymara language). There is no place for a solo performer in this music, reflecting a general emphasis on communal solidarity and cooperation as defining social values in most rural Andean communities.

Siku ensembles typically include 10 to 15 pairs of musicians, or 20 to 30 people, whose instruments are further differentiated by size, with several pairs of sikus tuned an octave or fifth above or below the main melody instrument. Three sizes of sikus, tuned to a low, middle, and high octave are most common, but here again great variation exists from one community to the next. In the sikuri (music and dance associated with sikus) tradition of Conima, Peru, for instance, studied by the ethnomusicologist Thomas Turino, no less than nine different voicings are used, including fifths and thirds, spread out over more than three octaves. Instrument makers also allow for slight variances in tuning from one octave or pair of instruments to the next, which produces a shimmering acoustic effect when the entire ensemble plays together. Virtually all pieces follow a similar formal structure, consisting of three individually repeated phrases (AABBCC).

Given the number of people and instruments required, the performance of sikuri music is restricted to large-scale festival contexts celebrated by the entire community, or sometimes multiple communities. Such festivals typically honor a particular Catholic saint or event in the Christian religious calendar. As noted, however, the roots and significance of a given festival may go beyond its surface Christian elements. Many festivals align with important moments in the agricultural cycle, such as planting or harvesting, and incorporate symbols from the pre-Hispanic past such as representations of the sun and moon, alongside Catholic iconography. In the region around Lake Titicaca, the largest annual festival, dedicated to the Virgin of Candelaria, takes place on February 2. “Mamacha Candelaria,” as she is affectionately known in Quechua, is also associated with the lake itself—the birthplace of the Incas, according to legend—as well as Pachamama, the feminine Earth Goddess or “Mother Earth” of Inca mythology, who is still widely revered throughout the Andes.

Sikuri music constitutes an important tradition on the island of Taquile, located twenty miles from the shores of Puno on the Peruvian side of Lake Titicaca. Like most communities in the vicinity of the lake, people on Taquile perform a variety of instrumental traditions, including flute ensembles, siku panpipes, and various string instruments, each played for a particular festival. Traditionally, Taquileños play sikuris during festivals held in the months of May and June. During these events, two different sikuri ensembles, representing the social division of the island into “upper” and “lower” halves, engage in an informal competition with one another by playing and dancing together in the central town square. Each group consists of roughly 30 male musicians, with several female dancers, drawn from their respective side of the island. Each ensemble maintains its own set of instruments and performs tunes specific to the occasion and to each group. The result, as the two groups play different tunes simultaneously in close proximity, each trying to sonically overpower the other amidst shouts of encouragement from community members, is sheer cacophony. From a Taquileño perspective, all the “noise” is a major part of the fun!

In order to comprehend this performance, you must also understand some of the ways in which the residents of Taquile are quite unlike any other indigenous community in the region. Beginning in the 1970s, drawn by the majestic beauty and mystique of Lake Titicaca, foreign travelers began touring the lake on boat tours. These tourists were particularly attracted by Taquile, which had a reputation as a source for exquisite handmade textiles and offered tourists a chance to experience what they imagined to be “uncorrupted” indigenous Andean life. Seeking to capitalize on this interest, Taquileños began shuttling tourists back and forth to the island on their own boats, and a booming tourist industry was born. Several decades later, this small island with only around two thousand inhabitants hosts up to thirty thousand tourists annually and has become one of the most popular destinations in all of Peru for foreign visitors. Island residents now make a majority of their income providing services like food and lodging for tourists, as well as selling textiles. Not surprisingly, these developments have had a major impact on virtually every aspect of Taquileño life.

Listening Guide 8.2 was recorded on Taquile during the Fiesta of Santiago in 2000. Traditionally, residents celebrated the fiesta on July 25 with groups of transverse flutes (called pitus) and string bands, followed eight days later with dances accompanied by kena flutes and percussion. Beginning in the 1980s, however, authorities began sponsoring a crafts fair during the festival in order to attract more tourists, taking advantage of the high season for tourism, as well as the proximity of Peruvian Independence Day on July 28. Organizers then altered festival customs further to present a variety show featuring all of the island’s music and dance traditions, drawn from the annual ritual calendar, performed daily over the course of two full weeks of the crafts fair. Though sikuris were not originally part of the Santiago festival, they now constitute the most important component of crafts-fair performances. In this particular recording, even the obligatory competition between lower and upper halves of the island has been eliminated. In order to give all performers some time off to get other work done, different groups perform serially on a rotating basis during the two weeks of the fair. The lack of a second, competing group, however, is the only notable change to the sound of this performance. In all other aspects, from the three-octave voicing of instruments to the AABBCC structure of the piece, it reflects typical performance practice.

Rather than competing with one another in an event of local religious significance, Taquileños now stage representations of their own traditions for foreign audiences, altering them to better accommodate audience expectations. Folklorists and ethnomusicologists often refer to this process of decontextualization and staged representation as folklorization. This should not, however, be simply dismissed as the corruption of a local tradition by foreign audiences. All traditions change, and in this case, the people of Taquile have been active participants in altering their musical practices to meet contemporary needs. Indeed, thanks to income generated by tourism to the island, Taquileños are now among the wealthiest “peasants” in Peru. They have managed to accomplish this while holding on to—indeed, by promoting—some of the oldest and most “traditional” aspects of their culture.

In depth

Indigenous music in the Andes today is not limited to flutes, drums, and vocal genres with pre-Hispanic origins. One of the most popular Andean instruments today is the charango, a small strummed or plucked lute that developed during the colonial era, representing a unique hybrid of European and Andean practices. Lutes, the instrument family to which both the charango and the guitar belong, arrived in the Andes in the sixteenth century. Attracted to this type of instrument, indigenous peoples invented their own version, altering several important features in accordance with their own musical sensibilities. Most prominently, the charango is much smaller than the guitar, similar in size to a mandolin. This gives the charango a higher “voice,” reflecting the general Andean preference for high-pitched sounds.

Charangos vary from region to region, depending in part on what materials are available locally. In parts of the southern Andes, instrument makers often construct the charango body out of the shell of the kirkinchu armadillo. In other areas, performers construct the instrument entirely out of wood, more closely resembling a small guitar. The number and type of strings on a charango also vary, reflecting both local custom as well as individual aesthetic choices. Mestizo versions of the instrument since the early-twentieth century have tended to use gut or nylon strings, but indigenous groups almost invariably utilize metal strings, producing a thinner and more cutting tone. Similarly, while the standard mestizo charango today has ten strings (tuned in five double courses: GGCCEEAAEE), and is often plucked to produce individual notes, indigenous charangos may have as few as four or as many as 15 strings, all generally strummed together.

Among indigenous groups in Southern Peru and Bolivia, the charango is often associated with courting practices, and the belief that charangos have a power to attract and seduce women. Indeed, in some regions men play the charango almost exclusively to attract women. Related to the instrument’s role in courtship activities is its relationship with mythical beings called sirenas (“mermaids” or “Sirens”) who inhabit rivers and lakes and are believed to imbue the charango with its seductive power.

Meanwhile, in urban and cosmopolitan contexts, the charango has continued to evolve. Virtuoso performers such as the Bolivian musician Ernesto Cavour promoted the instrument to national and international audiences beginning in the 1960s, helping to standardize its tuning and expanding its reach and popularity beyond indigenous or folk music audiences in the Andes. The singular charango grew to include a family of instruments, including the ronroco or bass charango that was utilized by bands like the Bolivian supergroup Los Kjarkas in the 1970s and 80s, and the Argentine composer and producer Gustavo Santaolalla, who incorporated it into unexpected musical realms such as the soundtrack for the Hollywood film “Brokeback Mountain.” Contemporary performers like Peruvian virtuoso Federico Tarazona have continued to experiment with the instrument, creating a hatun charango (“large charango”) with seven courses of strings designed to facilitate the performance of concert and Western art music repertoire.

Explore. For a sense of the extraordinary diversity of Andean Indigenous music, peruse the discs in the eight-volume Traditional Music from Peru series published by Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, as well as their earlier two-volume release, Mountain Musics of Peru. The films Dancing with the Incas and Mountain Music in Peru, both by John Cohen, also present compelling portraits of indigenous music, as does the more recent Sigo Siendo (“I Am Still Here,” 2013) by the Peruvian filmmaker Javier Corcuera. Beyond Peru, numerous recordings are available commercially from the Otavalo region in northern Ecuador and North Potosí in Bolivia, both renowned for their vibrant Indigenous musical life.

Mestizos, as noted earlier, are identified today less by their mixed Spanish and Indigenous ancestry than by their relative social position and cultural practices, which vary from region to region. In most parts of the Andes, mestizos are characterized as middle- to upper-class people who speak Spanish as their primary language, live in larger towns and cities, and engage in more “refined” pursuits and professional occupations. Many mestizo families are descended from hacendados, or hacienda owners, who formed the rural aristocracy until the early twentieth century. Upwardly mobile individuals from poorer or indigenous sectors of society might also achieve mestizo status through education, urban employment, and—importantly—by adopting mestizo cultural practices, including music. Conversely, in other areas, such as Peru’s Mantaro Valley or Bolivia’s Cochabamba region, most residents self-identify as mestizo, whether rural or urban, and the term connotes working class rather than elite identity.

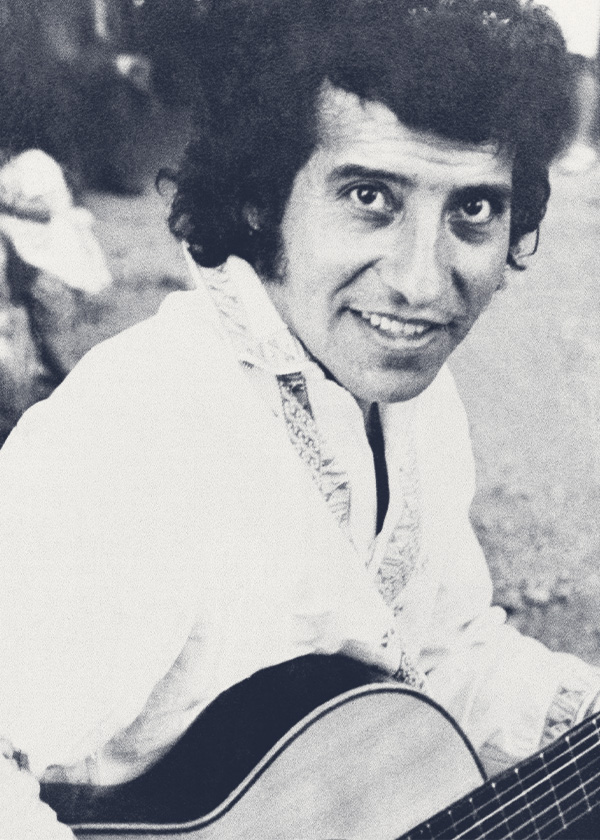

Defining “mestizo music,” then, has less to do with mapping a combination of Spanish and indigenous musical influences—though it may include these, and others—than it does with identifying the diverse kinds of music viewed as emblematic of a mestizo identity in a given locale. The discussion here focuses again on the Ayacucho region of Peru. The dominant mestizo instrument in Ayacucho is the six-string guitar, played with tremendous skill by people from the region, and often accompanied by other string instruments such as the mandolin. Many people believe that playing the guitar well is one of the hallmarks of a true Ayacuchan mestizo, and they refer to the region as the “cradle” of Andean guitarists. In keeping with their social position, however, most mestizos also believe that playing the guitar should remain an amateur pursuit, kept separate from an individual’s more reputable, and presumably more lucrative, profession. Even one of Ayacucho’s most famous musicians, the world-renowned guitarist Raúl García Zárate (1931-2017), continued to work as a lawyer even after his national and international performance career could have supported him financially. Being a professional musician, with very few exceptions, carries lower-class associations in the Andes.

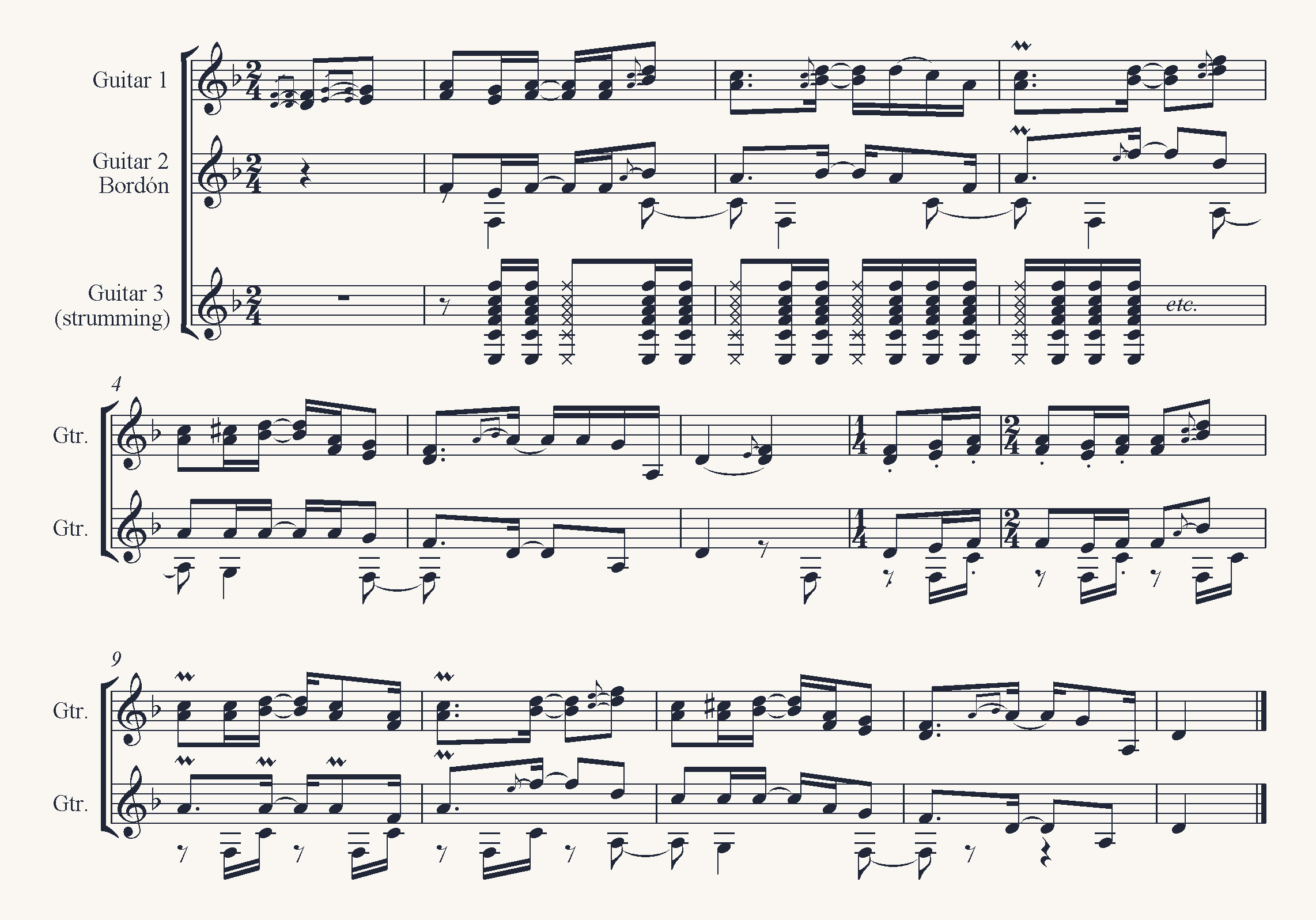

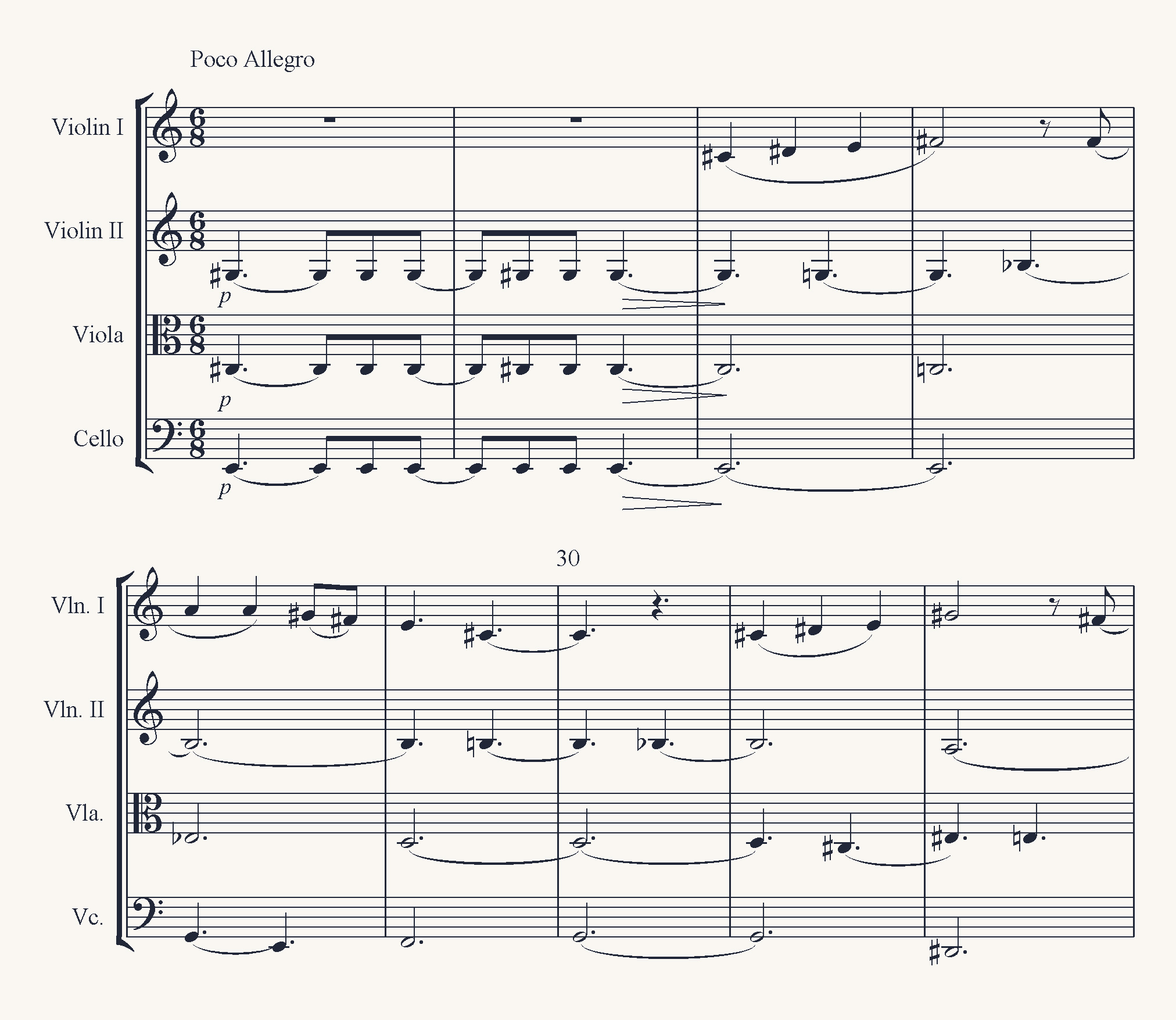

Nonetheless, part of the pride exhibited in the prominence of the guitar in Ayacuchan music is the technical difficulty of the regional style. One of its key features rests on the ability of the guitarist to simultaneously play a syncopated bass line, called the bordón, on the lower strings, while the other fingers pluck out a melody or strum on the upper strings. In the hands of a skilled guitarist, one guitar can sound like two or three playing at the same time. Other traits of the Ayacuchan mestizo style include extensive sixteenth-note passages in the introduction to most songs, or during instrumental breaks between verses, and frequent harmonization of the melody played on the upper strings, paralleling the vocal harmony (see Example 8.2). Mastery of this style is complicated by the presence of multiple guitar tunings corresponding to different genres that make playing their respective bordones (bass lines) easier.

Though the guitar may be played in public during certain festivals in Ayacucho, especially carnival, and at staged presentations of folkloric music, mestizos most frequently play it informally in private house parties. During such parties, a group of friends may gather for hours—sometimes, all night—to eat, drink, dance, and make music. Indigenous musicians, especially harpists, may also be hired to entertain at important mestizo family occasions such as a birthday or anniversary; part of their role is to accompany any mestizo guests who wish to play or sing, and to keep the festivities going between such moments. Until the mid-twentieth century, serenades were also a popular activity, in which a soloist or small group of musicians would visit another house, performing outside for the enjoyment of those who would come out to listen. This was a classic manner of courting, with a young man singing love songs to his intended bride.

Among the different genres of mestizo music, the wayno (also huayno, huayñu) is by far the most important and frequently performed. Found prominently throughout the central and southern Andes of Peru and Bolivia, the wayno originated early in the Spanish colonial era as a couples dance, and it remains the most popular genre in the region today. One remarkable aspect of the wayno’s diffusion is that it is performed and enjoyed by indigenous peoples and mestizos alike, though often with significant variations in instrumentation, tempo, and lyrical themes. Indeed, these differences are important indicators of class distinctions. Although indigenous waynos generally reflect the musical aesthetics of native communities, including a preference for high-pitched women’s voices, instrumental ensembles like panpipes or the harp and violin, texts in Quechua, and fast tempos for dancing, mestizo waynos are comparatively slower, sung in a lower key and/or octave, often by men, typically address more sentimental lyrical themes, and may be sung in Spanish or a mix of Spanish and Quechua. Unlike genres such as harawis or sikuris, performed at set times of the year and in particular contexts, the mestizo wayno may be performed at any time for secular entertainment.

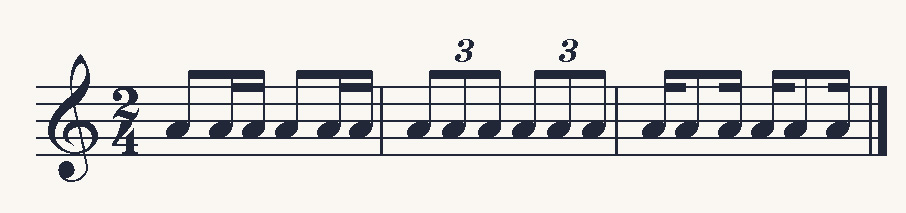

All waynos share several musical features. Rhythmically, the genre is identified by a repeated figure (bar A in Example 8.1), which musicians may vary substantially in the course of a performance (see bars B and C for examples of standard variations). This pattern is especially evident in the strumming patterns heard on instruments like the guitar and charango, or in the bass notes of the harp when a wayno is performed by a harp and violin. In the latter scenario, a third musician often reinforces the rhythm by striking the body of the harp with his knuckles. All waynos are strophic and follow a binary form in each verse (commonly AABB), and most rely on predominantly pentatonic (five-note) melodies set in minor keys. The prevalence of minor tonalities in Ayacuchan waynos have led many people to erroneously believe that they are inherently “sad.” Although some song texts do indeed address tragic or deeply sentimental themes, these are not related (as in Western music) to the minor key. On the contrary, many wayno texts address joyful and even mildly erotic themes and frequently engage in amusing wordplay. Finally, waynos typically incorporate a concluding section known as a fuga (“flight,” not to be confused with a “fugue” in the classical music definition of the term), in which the melody is shortened and the tempo may speed up slightly.

The wayno heard in Listening Guide 8.3, “Adiós pueblo de Ayacucho” (“Goodbye, Ayacucho Town”), is a classic of the Ayacuchan mestizo wayno repertoire. Written by an unknown composer around 1900, it was first recorded in the 1920s by a young harpist named Estanislaus “Tany” Medina, on one of the first recordings of Andean music. The song’s lyrics reflect the painful emotions aroused by its protagonist’s departure from his hometown and family, questioning whether he will ever return. At the time it was written, migration away from Ayacucho’s endemic poverty to the coast had just begun in earnest, and this song, along with others, emerged as an expression of longing for homes in the highlands. The song’s theme resonated in a poignant way at this performance in the 1990s, as many people had recently fled the Ayacucho region once again as a result of a decade of horrific political violence (see In-Depth 8.3). Nonetheless, when played at a brisk tempo in the context of an evening party or other festive occasion, “Adiós Pueblo de Ayacucho” can just as easily prompt a crowd to dance.

In depth

On May 17, 1980, a Maoist faction of the Peruvian Communist Party known as the “Shining Path” launched a guerrilla war from rural Ayacucho in hopes of toppling the Peruvian government. The guerrillas’ calculated use of extreme violence, coupled with a brutal counterinsurgency campaign by the Peruvian military, soon plunged the region into chaos. According to the final report of the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2003, nearly seventy thousand people were killed or “disappeared,” and hundreds of thousands forced from their homes between 1980 and the end of the conflict in the 1990s following the capture of Shining Path leader Abimael Guzmán.

In the midst of the violence, musicians in Ayacucho turned to their art as a way of bearing witness to the brutality of the conflict. Using traditional music forms, including the wayno, singers and songwriters built upon a deep tradition of social commentary in Andean music to forge a new song movement, one that spoke with a powerful voice of outrage, and at times, hope, in a climate otherwise marked by fear and silencing. Cassette tapes of canciones testimoniales (testimonial songs) soon circulated between Ayacucho and its scattered refugee population, while new star performers of this music emerged, including Carlos Falconí, Manuelcha Prado, and many others. Their songs continue to be performed and recorded today, providing a forum for the remembrance those deadly years.

Listening Guide 8.3, a live concert recording made at a prestigious concert hall in Lima and featuring two renowned contemporary Ayacuchan musicians, Manuelcha Prado and Carlos Falconí, captures all of the distinguishing characteristics of the Ayacuchan mestizo wayno. The performance begins with an instrumental introduction marked by heavily ornamented guitar lines played by both players (with a third guitarist providing strumming accompaniment), giving way to a less ornamented style during sung verses. Rhythmically, the syncopated bordón emphasizes the “upbeat” and often omits the downbeat altogether, typical of the Ayacuchan wayno. Spanish musical influence can be heard in the style of vocal harmonization, with a second vocalist frequently singing a third below the melody, while indigenous influence is apparent in the bilingual text, alternating between Spanish and Quechua. Finally, the performers end the wayno with a fuga, a short concluding verse. Though some waynos include a fuga composed specifically for that song, performers often draw upon a repertoire of relatively interchangeable ending verses that may be appended to any song. In this case, the musicians have opted to include a short, patriotic verse as a fuga in order to provide a more ringing and definitive conclusion to their concert.

This section has examined one of the emblematic musical genres of mestizo music from Ayacucho; in other regions, different influences have prevailed. To the north of Ayacucho in the Mantaro Valley of central Peru, for instance, the most important mestizo musical ensemble since the mid-twentieth century has been the saxophone orchestra, or orquesta típica, playing waynos and other regional styles of mestizo folk music. Farther south, in the Cuzco region, mestizo musicians have appropriated indigenous instruments such as the kena and charango and altered the way they are played to better fit mestizo aesthetics, as part of an ideological movement known as indigenismo (“Indianism”; see Chapter 3). In all cases, however, musical tastes and practices have been a crucial way of asserting a mestizo identity.

Afro-descendant peoples constitute a relatively small portion of the Andean population today, and are concentrated in just a few key locations: the Arica region in northern Chile, the Yungas Valley in northern Bolivia, the coastal region of central Peru, and the Chota River Valley and the Esmeraldas Province in northern Ecuador. In all of these places, they have mixed racially and culturally with the surrounding mestizo, criollo, and/or indigenous populations. Nonetheless, people who self-identify as Black have had a significant impact on the musical cultures of their respective countries in recent decades, and thus merit more discussion here than their small numbers might otherwise suggest. This discussion focuses on Ecuador, the smallest of the Andean countries, but the one with the largest Afro-descendant population.

Two distinct Black population centers exist in Ecuador, both with their own representative musical traditions. Enslaved Africans were first brought to the highland Chota River Valley by Jesuit priests in the seventeenth century, and their descendants continue to live in the valley today. Given their small numbers and their close relationship with surrounding mestizo and indigenous Quichua-speaking communities (an Ecuadorian dialect of Quechua), their musical traditions exhibit a mix of cultural influences. This is especially prominent in the musical genre for which they are most known, a dance music known as bomba. The typical musical ensemble for bomba includes one or more guitars, a smaller guitar known as a requinto, the small two-headed bomba hand drum, plus other percussionists and vocalists. Beyond these obvious Hispanic and African influences in instrumentation, the harmonic and melodic language of bomba music closely resembles the alternating minor-major tonality of Indigenous music, as does the Quichua-inflected Spanish in which most bomba songs are sung. In recent years, this music has become popular with a wider class of Ecuadorians, especially in fusion versions that combine this already-hybrid music with more mainstream and commercial popular music styles.

Several hundred miles to the west, the coastal Esmeraldas Province is home to the largest African-American population in the Andes, part of a larger cultural and geographic region that extends northward along the Pacific coast into Colombia. It is a green and verdant area, marked by dense mangrove swamps, hundreds of rivers, and a temperate rainforest that extends inland for more than a hundred miles. It is home to the marimba, a type of xylophone with African roots that is played together with several other drums and percussion instruments, accompanying a lead singer and chorus. Neither the instruments nor the music played by the marimba ensemble are exact copies of any particular African tradition. Unlike Afro-Cuban Santería or Brazilian Candomblé, which can trace aspects of their musical and religious practices to the Yoruba people of Nigeria, Afro-Ecuadorian musics are essentially creative hybrids, containing both Hispanic elements and a strong pan-African character.

The marimba ensemble typically includes a number of different percussion instruments: one or more marimbas, two cununos (a conical, single-headed hand drum), one or more bombos (a double-headed bass drum played with sticks), and numerous tubular bamboo shakers called guasás (all visible, except the guasás, in Figure 1.5).

While the marimba and drums are usually played by men, the shakers are often played by women known as respondadoras, who sing in “response” to the lead singer, known as a glosador. The latter may be a man or woman. Call and response relationships mark virtually all aspects of the music. Marimba parts are divided between the bordón, here referring to a repeated ostinato bass line, above which the tiple part improvises. Cununos are similarly divided between macho and hembra (male and female) parts that respond to one another.

Historically this music occupied a specific place in the lives of Afro-Ecuadorians, played at Catholic saint festivals and for secular entertainment at weekly dances, but today it is performed almost exclusively by amateur and professional folklore groups at large festivals and at beach resorts. These folklore groups first began forming in the early 1970s, when an elder generation of musicians grew concerned that not enough young people were learning to sing and dance the marimba tradition, due in part to mestizo antipathy towards Afro-Ecuadorian traditions, as well as to the slow incursion of foreign popular musics. Petita Palma formed one such group, “Tierra Caliente,” in 1972, and set out to train young singers and dancers through participation in her ensemble (see Figure 8.8). Hundreds of local performers have now passed through the ranks of her group and others, and many have gone on to found their own folklore troupes, both in Esmeraldas and in other towns and cities. Thanks to their collective efforts, the marimba has emerged in recent years as one of the principal symbols of a resurgent sense of ethnic and racial pride among Afro-Ecuadorians. One of the largest public celebrations in Esmeraldas is now the annual marimba festival held during Carnival in February, drawing thousands of spectators.

With a population of more than ten million people, more than a quarter of the population of Peru, Lima is one of the largest and most culturally vibrant cities in South America. Founded in 1535 as the seat of Spanish colonial power on the continent, for centuries it served as an enclave for Spanish elites and their criollo offspring, who remained culturally oriented to the fashions of Europe. This would not change significantly until the late nineteenth century, when a distinctive popular culture began to emerge from Lima’s working-class neighborhoods, followed in the mid-twentieth century by a massive wave of immigration from the Andean highlands that irrevocably changed the social makeup of the city. Today, Lima is home to a thriving and diverse popular culture, reflecting influences from all of Peru and beyond—from indigenous and mestizo folk music to upscale nightclubs featuring jazz, salsa, and rock. The following section explores some of these distinct musical scenes.

Criollo and Afro-Peruvian Music

Despite its reputation as a center for Spanish and European culture, Lima has always been a multicultural and multiethnic city. For much of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Afro-Peruvians outnumbered the Spanish and criollo population, and smaller but still significant numbers of mestizo and indigenous Andean peoples have also resided in the city since its founding. Although the aristocracy maintained its European cultural orientation following Peruvian independence in 1821, new cultural currents began brewing in working-class neighborhoods where other segments of the population lived and worked together. Concentrated in the callejones of central Lima—narrow alleyways with shared washing and cooking facilities, surrounded by rows of cheap dwellings—a new, syncretic popular culture emerged that combined African as well as Hispanic influences. One of the primary contexts for the development of this new hybrid culture was the jarana, a festive gathering filled with music, dancing, and food that sometimes went on for days.

Explore For a fascinating audio document of jarana musical practices, especially the marinera and associated traditions of improvised singing, look for the album Jarana’s Four Aces (Topic Records, TSCD926, 2005), based on recordings made in Lima in the 1950s.

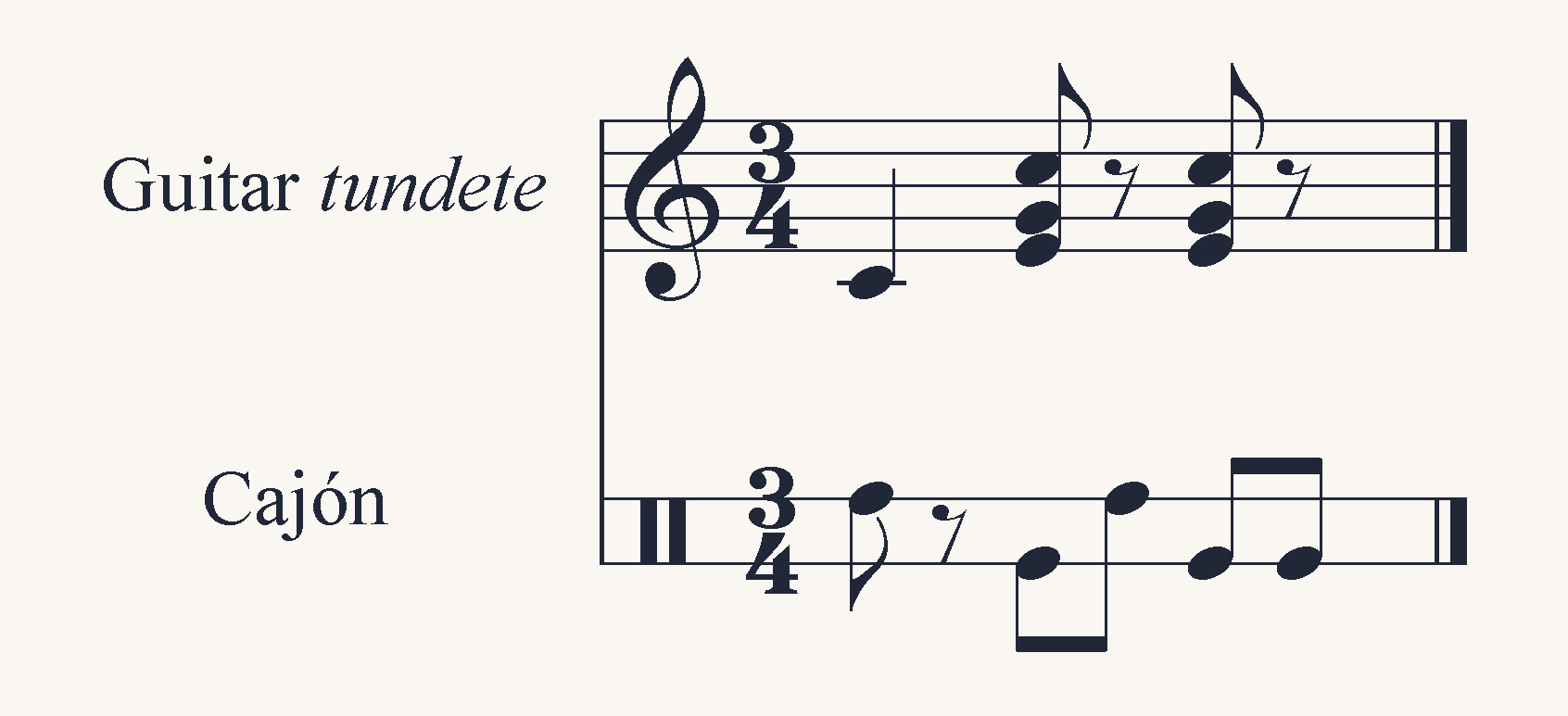

Though musicians played many types of music at jaranas, including the marinera, a syncopated 6/8 couple dance widely regarded today as Peru’s national dance (closely related to the Chilean and Bolivian cueca), the most popular genre at the turn of the twentieth century was the vals. A modified version of the European dance, Peruvian valses (as with their northern cousin, the Ecuadorian pasillo) maintained the genre’s 3/4 meter, but unlike the primarily instrumental European waltz, the vals was meant to be sung. Singers performed with one or more guitarists who played variations on a stock rhythm known by the onomatopoeic term tundete. Beginning with the thumb playing a bass note on beat one (the “tun”), guitarists then pluck and quickly dampen a chord on the top strings on beats two and three (“de-te”; see Example 8.3). Later in the mid-twentieth century, performers added the Afro-Peruvian cajón (wooden box drum; see Figure 8.9) as standard accompaniment for the vals.

The vals figured prominently in the musical life of the poorer working-class neighborhoods of the city. Paradoxically, though the genre today is recognized as quintessentially criollo, many of its most prominent innovators were Afro-Peruvian, or even of Chinese and Japanese descent. The criollo elite, for its part, initially shunned the genre as a debased version of the European original. Some of these class tensions were expressed in the music itself; while the lyrics of the “Old Guard” that pioneered the genre around 1900 primarily addressed romantic themes, a new generation of composers in the 1920s used the genre as a vehicle for more overt social commentary. Felipe Pinglo Alva (1899–1936), today hailed as one of the most important figures in the history of this music, penned his biggest hit with “El Plebeyo” (“The Plebian”), which narrates a poor man’s lament over the impossibility of love for an upper-class woman:

Mi sangre, aunque plebeya

También tiñe de rojo

El alma en que se añida

Mi incomparable amor

Ella de noble cuna

Yo un humilde plebeyo

No es distinta la sangre

Ni es otro el corazón

¡Señor! ¿Por qué los seres

No son de igual valor?

My blood, although poor

Also stains red

The soul in which nests

My incomparable love

She of noble birth

I, a humble working man

Our blood is no different

Nor our hearts distinct

Lord! Are all people

Not of equal value?

Pinglo notably incorporated influences from foreign genres then popular into his music, ranging from Argentine tangos to North American jazz, further contributing to the developing sound and harmonic language of the vals.

By the 1930s, middle- and upper-class audiences in Lima gradually accepted the vals. Early commercial radio played an important role in this process, as it began featuring music programs that helped legitimize the vals and associated genres. A second reason for the wider acceptance of this music was a surge in Peruvian nationalism and a consequent search for national symbols. This current swept across Latin America in the early twentieth century, as the challenges brought on by economic modernization, industrialization, and urbanization left governments and citizens scrambling to redefine themselves.

Not surprisingly, the search for a national culture brought old social rifts to the fore. Mestizo intellectuals and elites in the highlands turned to indigenous references, especially those dating to the Inca Empire, as a way of defining “Peruvian-ness.” Collectively, their efforts gave birth to the movement known as indigenismo (“Indianism”), though it rarely acknowledged or even engaged with the Indigenous population itself. Middle- and upper-class elites in Lima, on the other hand, sought symbols that could represent a culture that was at once “Peruvian” as well as “coastal,” in order to justify their economic and political control over the country. The vals, marinera, and associated forms of criollo music fit the bill, despite the poor opinion many elites previously held of such genres. By the 1940s and 1950s, they were being promoted in the capital as the national music of Peru, and the Peruvian Congress even declared a national annual “Day of Criollo Song” in 1944.

The most celebrated singer and songwriter of criollo music during this era was María Isabel Granda Larco, better known as Chabuca Granda (1920–1983; see Figure 8.10). Raised in an upper middle-class family in Lima, she formed a lifelong association with the city and its popular culture. Her most famous composition, the vals “La Flor de la Canela” (Cinnamon Flower), captures both the spirit of criolloismo (criollo-ism) in mid-twentieth century Lima, as well as the evocative and sensual poetry that was Granda’s trademark. “La Flor de la canela” offers a nostalgic and romanticized view of an older (and more exclusively criollo) Lima, evoking specific places such as the bridge that passes over the Rimac River in the center of the city. Granda personifies the city as a young, mulata woman with “jasmine in her hair and roses in her face,” a genteel allusion to the Afro-Peruvian influences on criollo music.

The immediate and sustained popularity of “La Flor de la Canela” among criollo audiences represented a reaction against Lima’s rapidly changing social and musical environment. Uncontrolled population growth and industrialization altered the very face of the city, erasing many signs of its colonial past and its historically criollo identity. Members of the elite viewed such changes with alarm, and the idealized vision of their city’s past as expressed in songs like “Flor de la canela” undoubtedly comforted them.

Importantly, Afro-Peruvian musicians, who played such a critical role in the development of criollo music, and who remain some of its most popular performers today, also began reclaiming their own musical heritage in the 1950s. The Afro-Peruvian revival, led by the siblings Nicomedes and Victoria Santa Cruz, demanded recognition for Afro-Peruvian contributions to criollo music, even as it promoted more exclusively Afro-Peruvian genres such as the festejo and the landó as symbols of a separate identity. Chabuca Granda—who was not Afro-Peruvian—also championed these genres later in her life, and her song “Maria Landó” became famous internationally in the 1990s as performed and recorded by Afro-Peruvian singer and folklorist Susana Baca. Indeed, Afro-Peruvian music has proven far more successful than criollo music in so-called world music markets in the U.S. and elsewhere in recent years, and Baca herself won a Latin Grammy for “Best Folk Album” in 2002 for her CD Lamento Negro (Black Lament).

Explore The Afro-Peruvian compilation CD produced by David Byrne, Afro-Peruvian Classics: The Soul of Black Peru (Luaka Bop, 1995), first spurred international interest in Afro-Peruvian music, and it remains useful for its selection of historic tracks by key artists. Look also for solo CDs by musicians including Susana Baca, Eva Ayllón, and the group Perú Negro.

Though the Afro-Peruvian revival presented a challenge to Lima’s criollo exclusivity, the biggest change in Lima in the 1950s was the explosive growth of the Andean immigrant population. This “Andeanization” of Lima ushered in a new era in the city’s popular music, and added yet another layer to the texture of Peru’s musical cultures. Though criollo music continues to be viewed as the “national music” of Peru in certain contexts, its historic claim to that title has been challenged repeatedly with the advent of a sustained Andean music scene in the capital.

Between 1940 and 1960, Lima’s population nearly tripled, jumping from just 650,000 residents to more than 1.8 million; it almost doubled again in the following decade and has continued to grow ever since. Most of this growth resulted initially from migration from the rural Andean highlands. Migrants came for many reasons, but their principal motivation was financial: Lima held the best prospects for employment as well as education. Migrant hopes for a better life, however, often met a bitter end in Lima’s shantytowns, or pueblos jóvenes (young towns). Marginalized in their new surroundings and dismissed as cholos (a derogatory term for urbanized Indians), migrants turned to one another for support, and decades would pass before they achieved middle-class status in significant numbers.

Along with their meager possessions, migrants brought music and musical tastes to the capital. Nostalgia for the highlands and for family and friends left behind, coupled with an emergent sense of identity as provincianos (provincials), provided the impetus for creating new forms of urban Andean repertoire. In the 1950s, an entire industry developed around this new music. Entrepreneurs organized Sunday afternoon concerts in coliseos (outdoor sports arenas or large tents) in which hundreds of spectators gathered to listen to music, eat typical highland food, and socialize. AM radio stations began broadcasting early morning shows dedicated to highland music, as well as announcements and news directed at the migrant community. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, a national recording industry developed that recorded and distributed Andean music, accounting for half of national sales between 1950 and 1980.

Musically speaking, the Andean music that first developed in Lima built upon mestizo traditions from the highlands, with several adaptations. The most prominent change was an emphasis on solo singers who performed with a band in a staged environment. As previously discussed, in the highlands great emphasis is often placed on the group nature of performance. In Lima, however, a star system emerged among performers, most of whom adopted folksy stage names that stayed with them throughout their careers, such as Jilguero de Huascarán (The Goldfinch of Mt. Huascarán), El Picaflor de los Andes (The Hummingbird of the Andes), and Pastorita Huaracina (The Little Shepherdess of Huaraz). Literally thousands of such figures emerged in the mid-century.

These names reflected the kind of rural persona promoted in the music—similar to that of urban country music in the United States—and also reflected the continued importance of regional identities among migrants. Singers chose specific places from their home areas as part of their stage names, and reinforced that association by wearing folkloric clothing. Most importantly, they also chose their backup ensemble to reflect a particular region. El Picaflor de los Andes (Víctor Alberto Gil, 1929–1975), for instance, came from the Mantaro Valley, located east of Lima, and employed a saxophone orchestra from that region. Pastorita Huaracina (María Alvarado Trujillo, 1930–2001) migrated from the Ancash region, and performed with a string band representative of mestizo practices there (Figure 8.11), while the trio Lira Paucina (The Lyre from Pauza) played the guitars and charangos associated with southern Ayacucho. Audiences for such groups, however, came from areas all over the highlands.

The wayno dominated the repertoire performed by these singers and musicians. Though certain new performance practices emerged in the city, such as the interjection of verbal comments by the singer during instrumental interludes, a practice developed in radio broadcasts, the formal structure of the wayno remained intact with its characteristic rhythm, tonality, and pentatonic melodies. This fidelity to the wayno’s original form and regional styles also helped to popularize migrant singers back in their home provinces, where recordings began circulating soon after being released in the city.

The performance of a commercial wayno from the 1970s featured in Listening Guide 8.5 gives a sense of such changes and continuities, as well as some concerns expressed in the lyrics of Andean migrant music. “Neblina blanca” (White Fog) is a chuscada, a regional wayno variant from Ancash, recorded by Basilia Zavala Camones, “La Huaracinita” (The Little Woman from Huaraz). On this recording, she is backed by a traditional Ancash string band, including guitar, violin, harp, and an accordion. The song follows the typical AABB form of most waynos, concluding with a fuga section, and harmonically alternates between the usual minor and relative major.

Lyrically, “Neblina blanca” typifies many waynos in lamenting a lost love, but also contains elements of social critique reflecting the difficulties of migrant life. It begins with a statement of despair: “White fog of the month of May / It is you who steals the hopes of my passionate heart.” “White fog” is a specific reference to life in Lima, where a mist hangs over the city for nearly nine months a year, thanks to the cold Humboldt Current that runs just off its shores. On a more subtle level, the “white fog” of this song could also be a metaphoric reference to Lima’s criollo (i.e., “white”) culture, and the demoralizing climate of prejudice faced by highland migrants to the city.

In the second verse, the singer bemoans the loss of an unnamed love, noting that she has traveled “around the world” but has never found “similar affection as yours.” Although on its surface this is a straightforward romantic lament, when heard in the urban context it echoes the kind of nostalgia felt by many migrants for the familiarity of highland life they left behind. Finally, in the fuga, nostalgia turns to a condemnation of those migrants who forget where they are from and turn their back on their heritage. Much like musical taste, an individual’s choices in food and drink are often indicative of social identity. In this case, the singer condemns her old lover for drinking “dark beer,” an expensive beverage in Peru, with his “millionaire friends,” while she remains true to the migrant community by drinking chicha de jora, homemade corn beer.

By the 1980s, the “golden era” of the Andean wayno in Lima drew to a close. Competition from foreign genres, including Latin pop and salsa, and the development of variations of cumbia that appealed to second- and third-generation migrants (see In-Depth 8.4), contributed to the wayno’s decline. Nonetheless, classic recordings by stars from the earlier era continue to sell well today, and new styles of wayno have emerged in recent decades. Beginning in the 1990s, younger musicians from Ayacucho introduced synthesizers, drum set, electric bass, and pan-Andean instruments like the kena and panpipes into the traditional guitar-based mestizo Ayacuchan sound, and forged a style—simply called música ayacuchana, “Ayacuchan music”—performed by stars like Max Castro and the Duo Gaitan Castro, that remains popular today. Another style of contemporary wayno, featuring the strident, high vocal style of indigenous Andean music accompanied by amplified steel-string harp and drum machine, sometimes called wayno con arpa (harp wayno), has also become tremendously popular among working-class listeners. In a sign of the changing social perception of Andean peoples in the capital, a 2004 television series about the life of wayno con arpa singer Dina Paucar captivated Peruvians of all social classes, and catapulted Paucar into the national limelight.

New Andean Pop

In addition to the revitalization of older genres, a new and vibrant wave of Andean popular music utilizing the Quechua language has emerged in the new millennium in Peru, blending traditional Andean sounds with contemporary genres like reggaetón, hip hop, and electronic dance music. One of the earliest trailblazers was Uchpa, a hard-rock and blues band formed in Ayacucho in the 1990s. Uchpa gained acclaim by performing Quechua-language covers of classic rock and blues songs by artists like Nirvana, later crafting original Quechua songs like the wayno-infused “Chachaschay.” Their 2000 album Qukman Muskiy (“Different Breath”) brought Quechua rock into Peru’s mainstream, proving indigenous language and modern genres could thrive together.

Expanding on this framework, Damaris Mallma emerged as a prominent figure in the early 2000s fusing Andean folkloric music elements with softer contemporary pop styles, including frequent use of the Quechua language. Born in the highland city of Huancayo and active since childhood, Damaris first began performing with her mother, prominent folk singer Victoria de Ayacucho (also known as Saywa), before beginning to write original material while still in her teens. She was the first Peruvian artist to win Chile’s Viña del Mar International Song Competition with a Quechua-language song—“Tusuykusun” (“Let’s Dance”)—in 2008, followed closely by a Latin Grammy nomination for her album Mil Caminos. She remains active as a performer and recording artist today, utilizing both Quechua and Spanish on recent albums released to global audiences.

While Uchpa and Damaris showed the potential for Quechua-language music in mainstream markets, contemporary Quechua rap artists like Renata Flores and Liberato Kani are pushing boundaries both musically and politically. Hailed as the “Queen of Quechua Rap,” Renata Flores was born in 2001 in Ayacucho, and first captivated audiences as a teenage singer with Quechua-language covers of hits by Michael Jackson and Alicia Keyes before transitioning to original trap, hip-hop, and rap tracks with socially charged lyrics. Her 2021 album Isqun addresses issues such as gender violence, environmental degradation, and indigenous pride, positioning Quechua-language performance within modern protest and pop cultures in Peru. Similarly, rapper Liberato Kani’s music and political activism, embodied in his 2016 debut album Rimay Pueblo, positions the use of Quechua as an explicit act of cultural resistance, defying the historic and continued marginalization of indigenous peoples in Peru. The popularity of their music marks a cultural shift in the Andes, where indigenous languages and identities are no longer relegated to the rural periphery, but are rather gaining visibility in mainstream media and youth pop culture. Platforms like TikTok, YouTube, and Spotify have also allowed Quechua-language artists to reach international audiences directly, contributing to a growing appreciation of Andean cultures and their diversity worldwide.

In depth

Commercial recordings of the Colombian cumbia burst onto Peru’s musical scene in the 1960s. Within a decade, Peruvian bands were playing their own versions of the genre, experimenting with instrumentation and musical forms, and creating what would eventually coalesce into discernable “Peruvian” variants. Early bands like Los Destellos, led by electric guitarist Enrique Delgado, drew on influences from surf rock and psychedelic music of the 1960s to craft a shimmering, hypnotic sound that differed substantially from its Colombian origins and became a hallmark of the genre. Los Mirlos, another pioneering Peruvian band from the Amazonian region, experimented further with additional guitar and keyboard effects, which eventually coalesced into a recognizable “psychedelic cumbia” subgenre that remains popular today.

Cumbia held a special appeal for the children of Andean migrants in Lima. Caught between a city that refused to fully accept them, and a highland culture they had never truly known, second-generation provincianos found in cumbia a modern, cosmopolitan genre with which they could identify. Given the similarity of the basic rhythms underlying both the wayno and cumbia, influences from the former were easily incorporated into the latter, and a number of early hits borrowed wayno melodies. The resulting music, fusing electric guitars and bass, Latin percussion like bongos and timbales, Andean melodic motifs, and lyrics about working-class migrant life in the city, became known as cumbia andina or chicha (after the fermented corn drink). The band Los Shapis and the singer Chacalón (Lorenzo Palacios) were two of the biggest chicha stars of the 1980s, and their recordings still circulate today.

Cumbia also took root in Peru’s Amazon region. This “tropical” variant, centered at first in cities like Iquitos, had few of chicha’s Andean influences. The style spread to the rest of the country in the 1990s, where it eventually became known as technocumbia. In contrast to chicha, which had never gained the approval of Lima’s middle and upper classes, technocumbia captivated a broad cross-section of the listening public; according to ethnomusicologist Raul Romero, this was arguably the first time that a single musical style had achieved such popularity in Peru across social, class, and ethnic lines. In place of Andean influences, technocumbia referenced pan-Latin American popular dance music forms and included strictly romantic lyrical themes. This contributed to its broad appeal, as did the provocative dress and suggestive choreography of its mostly female performers. The singer Rossy War (see Figure 8.11) catalyzed the technocumbia boom with her 1998 hit “Nunca Pensé Llorar” (I Never Thought to Cry). Her most common stage outfit was a modified version of the revealing black leather attire worn by Selena, the Mexican-American performer of tejano music (see Chapter 10). Rossy War’s hoarse, alto vocals are modeled after that of another Mexican musical icon, the popular singer Ana Gabriel. If earlier versions of chicha emphasized ways to “localize” cumbia and make it meaningful on Peruvian terms, technocumbia took it in the opposite direction, attempting to “globalize” it by incorporating disparate elements and influences from abroad.

Technocumbia artists continue to perform and record, while recent years have also witnessed a resurgence of older cumbia and chicha artists, as well as the popularization of salsa-influenced cumbia orchestras from Peru’s northern coast. Psychedelic cumbia made a tremendous comeback in the 2000s, exemplified by the already-mentioned cumbia pioneers Los Mirlos performing at the Coachella music festival in 2025—the first Peruvian band ever invited to perform there, more than fifty years after the band’s founding. Newer groups, such as Bareto, have also revived older cumbia hits and fused them with new influences from ska, reggae, and other transnational pop genres, winning new international audiences and Latin Grammy nominations along the way. Finally, some of the bigger Peruvian cumbia stars have recently been the subject of documentary films and biographical miniseries on national television back at home in Peru—a true sign of changing attitudes and audiences for this formerly “lowbrow” music.

t this point, you might reasonably be asking how the music examined thus far connects with the “Andean music” you are most likely to have heard before. Search on the Internet or any streaming service for “Andean music,” and you will undoubtedly find recordings of bands wearing ponchos or colorful hand-woven vests, playing a combination of instruments that includes panpipes, the kena flute, a charango, a bombo bass drum, and one or more guitars. The music might include stylized versions of indigenous or mestizo music repertoire, but probably also includes covers of other Latin American popular music, hits from the United States, and even new age compositions foregrounding breathy panpipes over synthesized sounds. Where did this music come from, and how did it come to represent “the Andes” for international audiences?

According to ethnomusicologist Fernando Rios, the “Andean music ensemble” of today emerged primarily in Buenos Aires and Paris, rather than in the Andes themselves. As explored in Chapter 7, rural folk music styles in Argentina were performed in peñas (folk music clubs) in Buenos Aires as early as the 1920s, where Andean genres also had a limited presence. By the 1940s, Andean influence had grown, bolstered in part by the presence of Bolivian and Peruvian musicians. Attracted to indigenous repertoire, but not bound by the practices of any specific tradition or community, these groups experimented with new combinations of instruments. One of the most prominent Argentine groups, Los Hermanos Abalos (The Abalos Brothers), performed with a lineup that incorporated the kena, charango, bombo, and guitar, standardizing a model for “neo-Andean folklore”—another example of folklorization—that would influence the presentation of Andean music internationally for many decades.

By the 1950s, recordings and artists like Los Hermanos Abalos had traveled, along with other Argentine musicians, to Paris, where their stylized repertoire captured the interest of listeners in the bohemian clubs of the Latin Quarter. Folk music clubs that programmed Andean groups became trendy nightspots. One, L’Escale (The Stopover), became famous for both its Andean music and as a hangout for celebrities like actress Brigitte Bardot. Few musicians who played there, however, had any personal connection to Andean music cultures. Indeed, the most prominent band of the Andean music craze, Los Incas, consisted of two Argentine and two Venezuelan musicians who had never played Andean music at all before moving to France. Nonetheless, the virtuosic way in which they and others performed appealed to international audiences, and contributed to the dissemination of this new sound.

Recordings and tours by such groups eventually made their way back to the Andean region itself, where they met with varied reactions. In rural communities and among urban migrants, this music never became popular. Among middle-class audiences, however, especially college students and other urban mestizos, neo-Andean folkloric music steadily grew in popularity from the 1960s onward. In Bolivia, groups like Los Jairas, founded by Swiss kena player Gilbert Favre, became a national sensation and played regularly at their own club in La Paz when not on tour internationally. In the 1970s, the previously-mentioned Bolivian group Los Kjarkas emerged as arguably the most influential folklore group of the region. Their song “Llorando se fue,” based on the rhythms of a Bolivian genre known as caporal-saya, circulated worldwide in the late 1980s as accompaniment for the lambada dance craze.

One of the performers at the L’Escale club in Paris in the 1950s and early 1960s was the noted Chilean folklorist and songwriter Violeta Parra. When she and her two children, Ángel and Isabel, returned to Chile in 1965, they helped launch one of the most influential musical movements in the history of Latin America. Known as nueva canción (“new song”), this movement fused Latin American folk music styles, especially the influences the Parras brought back from Paris, with leftist political sentiments then surging among students in Southern Cone countries.

As in many parts of the world, the 1960s and 1970s were a turbulent time in the Andes. Student groups, labor unions, and peasant federations took to the streets, and in some cases, took up arms, in attempts to address widespread poverty and severe social inequalities. In the context of the Cold War, many adopted explicitly Marxist politics and goals, viewing the Cuban Revolution of 1959 as a model for the rest of Latin America. Alarmed by such developments, conservative political forces sought to protect their economic interests and limit the gains made by these groups. Though the confrontation varied in its details and intensity from one country to the next, its polarizing effects were most striking in Chile, where conflicts between right and left reached their peak during the presidency of Salvador Allende in the early 1970s.

Nueva canción grew out of this struggle. Just prior to the Parras’s return to Chile, in 1963, a group of poets, musicians, and writers in Mendoza, Argentina, including a young Mercedes Sosa (see Chapter 7), published a manifesto in which they called for a nuevo cancionero, or “new songbook,” that drew inspiration from that country’s folkloric music, but without being limited by its traditional canons. The group hoped to create a new, socially and politically conscious form of folk music. Inspired by their model, as well as by North American singers like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez, young Chilean musicians began creating songs that conspicuously incorporated Andean instruments and influences (see Figure 8.13). These musicians played a crucial role in the election of Salvador Allende, candidate of the leftist Popular Unity coalition, who took office as the president of Chile in 1970.