INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this appendix is to explore the world of sound as music, treating the various means of manipulating sound to create music and the terms and concepts associated with doing so. In this way, you can acquire a vocabulary for describing and understanding what you hear in music. Reading this appendix in advance will help you to assimilate the material in the previous chapters much more easily, and it will facilitate discussion of the musical examples to which you will be listening.

Each listening example is accompanied by a listening guide, which provides you with a summary of information about the piece, its composers and/or performers, the performing media involved, its form, rhythm, and other salient aspects. Then a table lays out the major events in the piece, providing both descriptions and timings so that you can follow along. The text below includes references to listening examples, figures, and musical examples throughout the text that help to illustrate the terms and concepts in question.

It may seem an obvious thing to state that all music consists of sound. But sound is a phenomenon that requires thoughtful treatment, for it is more complex than you may imagine. To begin, what constitutes musical sound? Is any kind of sound potentially music, regardless of its origin or purpose? The authors of this textbook prefer the definition that John Blacking provided in his 1973 book How Musical Is Man? That is, music is humanly organized sound. It is crucial to bear in mind, however, that this is only one perspective and not relevant to all cultures. In many languages, such as Quechua and Náhuatl in Latin America, there is no single word for music itself, but many terms and phrases referring to various kinds of musical performance. In fact, there are many ways that people can relate to the sounds of their immediate environment, and those they make themselves, as music. These are inevitably based in local culture.

There are two basic kinds of sound in music: unpitched and pitched. Unpitched sounds are sometimes called noise, a word people often use in a pejorative sense to describe music they do not like, to assert that it is not really music at all. But the reality is that unpitched sound plays a crucial role in most kinds of music (for instance, the sound of a cymbal crash, or the beat of a bass drum). The difference between unpitched and pitched sounds is easy to summarize: an unpitched sound has an irregular waveform or vibration, while the waveform of a pitch is uniform and regular in shape.

Like pitches, unpitched sounds may be lower or higher, but they lack peaks of intensity occurring over regular periods of time (cycles per second, or cps). Instead, their frequencies are spread more evenly across a broad spectrum. Pitches have measurable frequencies. For instance, in the United States, “concert” A, the pitch to which orchestras tune up, is currently 440 cps. Every pitch has its own rate of vibration. The distance between any two pitches is called an interval. The most basic interval is an octave, the point at which the frequency of a pitch is doubled or halved. An octave above A-440 is A-880; an octave below, A-220 (other intervals will be treated further on).

In short, when you snap your fingers, the resulting sound is unpitched; when you hum a tune, you use pitches. Both are musical sounds. In a rock band, the drum set consists largely of unpitched instruments. Electric guitars produce mostly pitches. Both unpitched and pitched sounds combine to create music.

In fact, there is a universe of sound generators, some of which produce unpitched sounds, some pitched, and many both. The most obvious examples are the human voice and body. The human voice is capable of great subtlety and variety in the sounds it can produce, and vocal production is the term one uses to describe the quality of a singer’s voice, whether it is rich, full, nasally, pinched, throaty, and so on. The basic types of vocal categories correspond to how high or low they sing: female voices from high to low are soprano, mezzo-soprano, and alto; male voices, tenor, baritone, and bass. In addition to the voice, the fingers, hands, and feet can all be used as percussion instruments through snapping, clapping, and stomping.

Beyond the body, there are four traditional categories of sound generators, as well as a more recent addition. The first is membranophones: instruments that are meant to be struck (called percussion) and that produce sound by means of a membrane, made of animal hide or synthetic material, that vibrates when hit with the hands or with sticks (mallets). An Aztec huehuetl is an example of a membranophone (see Fig. 2.2 and Listening Ex. 2.2, 0:00-1:03).

The second is idiophones: percussion instruments that do not employ a membrane and whose sound derives directly from resonance of the object itself. Woodblocks, cymbals, or chimes are all idiophones, because sound results from striking wood or metal directly. Again, the striking element may be hands, sticks, or some other object. The Aztec teponaztli is a good example of an idiophone (see Fig. 2.1 and Listening Ex. 2.1, 0:00-1:13).

The third category consists of chordophones: instruments that produce sound by means of a vibrating string, as on type of guitar called a cuatro (see Fig. 5.4 and Listening Ex. 5.4, 0:00-0:09, 0:32-0:43). Strings may be set in motion with a bow (violin), the fingers or a plectrum (guitar), or with hammers (piano). The root word—chord—does not refer to harmony (see below) but rather to a string of some kind, whether of animal sinew, silk, metal, or nylon.

The final traditional category is aerophones: instruments that produce sound by means of a vibrating column of air, as on the Andean panpipes (see Fig. 8.4 and Listening Ex. 8.2, 0:00-0:36). The flute, trumpet, and saxophone are all aerophones. The column of air may be set in motion by blowing over a notch or hole (flute), or by blowing on a reed or double reed pressed between the lips (clarinet, oboe, bassoon). All brass instruments use a cup mouthpiece, into which one buzzes one’s lips to create the vibrating column of air. Holes, keys, or valves on an aerophone allow for adjusting the length of the instrument to accommodate different pitch frequencies.

One additional, more recent, category consists of electronic instruments, or electrophones, such as synthesizers and computers. These produce electronically generated signals that can be modified in an almost limitless number of ways (see Listening Ex. 9.5).

Obviously, some instruments represent a sort of hybrid, like the electric guitar or electric piano. The organ, an instrument very prominent in Latin American churches and cathedrals, is basically an aerophone, as its sound is produced when air is forced through pipes. Before the age of electricity, wind entered a pipe opened by means of mechanical keys. In modern times, this mechanism is often electronic. A synthesizer can simulate the sound of almost any instrument.

A composer thus has a very wide variety of sound generators to choose from when writing a piece of music. The term instrumentation refers to the instruments that a composer or musicians have chosen to use in a particular piece. Orchestration refers to the art of deciding how to combine various instrumental parts in a composition.

What distinguishes the sound quality of Colombian gaita flutes (see Fig. 4.11) from that of a guitar, even if they are playing exactly the same pitch? The physical characteristics of a sound generator (i.e., the parts of it that resonate) determine its sound quality, known as tone color or timbre. In fact, it is possible to elicit a variety of timbres from the same instrument. For instance, if I pluck the string of an acoustic guitar with a hard plectrum, or pick, the resulting sound will be rather strident and tinny. If I pluck it with a pick made of felt, the sound with be much mellower. The same effect can be produced by plucking it first back by the bridge (where the strings attach to the body of instrument), and then over the sound hole or neck. To understand how this is possible, and how different timbres are created in the first place, it is necessary to understand the concept of overtones.

Just as white light is a composite of various colors (frequencies), so any pitch produced on an instrument or by the human voice is comprised of many notes called overtones, which form the overtone series. This is a sequence of higher notes that combine together in the background when a fundamental note is played and help generate its characteristic timbre. For instance, if you play a C in the lower register of the piano, above that fundamental note will sound (even if you cannot hear them easily) another C, then G, C, E, G, B-flat, C, and many other pitches beyond those. These are the overtones (also called partials or harmonics). They provide richness and variety to musical sound.

Because of its unique construction, when a gaita flute plays that C, certain overtones are stressed more than others. This pattern gives it a timbre that is different from that of a guitar, because the guitar will stress other overtones. To return to our example on the guitar, if I play with a hard pick (or fingernails) or back by the bridge, where the string tension is very high, I will bring out the higher overtones, producing a strident timbre. Conversely, playing with a soft pick or the flesh of my finger, or over the sound hole where the tension is lower, will bring out the lower overtones, lending a softer quality to the sound.

One last crucial element of sound pertains to its intensity or dynamics, how loud or soft a sound is. If pitch is determined by the frequency of a sound wave’s vibration, and if tone color is the product of its overtone series, then intensity arises from the amplitude of the sound. That is to say, the actual height of the sound wave, not the frequency of its movement past a fixed point, determines how loud or soft a sound is. The guitar again provides a useful means of illustrating this simple point. If I pull a string back as far as it will go, it will vibrate back and forth across a wider area than if I use minimum force to displace it from its point of rest. In other words, the farther back I pull the string, the louder the sound it makes. For the same reason, the harder I hit a drum head, the louder the resulting sound will be, because I have displaced the head farther than by hitting it gently. The sound waves thus generated will be larger (though not faster), i.e., they will have greater amplitude.

An electric amplifier takes the signal from an instrument, via a pickup, and increases (amplifies) the size of the sound wave. Until you plug it into an amp, a solid-body electric guitar makes a very soft sound, because the thick wood does not resonate easily. An acoustic guitar has its own built-in amplifier: the soundboard and hollow body of the instrument amplify the sound made by plucking or striking the strings, and it projects out of the hole on the front. High volume or intensity is often referred to by the Italian word for strong, forte, while passages of lower intensity are described as piano (soft). A gradual increase from soft to loud is called a crescendo, and from loud to soft, a decrescendo.

Exercise Appendix.1: Intensity. Listen to Listening Ex. 3.10 and compare the intensity level of the opening (0:00-2:00) to that of the conclusion (6:01-7:04). Does the work get softer or louder, and how is the shift in dynamics accomplished?

The term rhythm describes the way that musical sounds are organized over time. In its most basic sense, rhythm refers to the relative durations of musical sounds. I say “relative” because one perceives the length of any musical event in relation to events around it. A note of some absolute duration may seem longer or shorter depending on what goes on before and after it. For instance, a note one second in duration will seem very long if preceded and followed by notes lasting only a fraction of a second. Conversely, it will seem quite short if surrounded by notes of several seconds’ length. There is an almost infinite number of possible sound durations and combinations of rhythms, which musicians exploit to great effect.

Another dimension of rhythm has to do with beat, a regularly occurring form of rhythmic organization in a piece of music. Though most music has a beat, it is not necessary in a musical composition, and there are kinds of music without a pronounced beat or pulse; they are referred to as ametrical or unmetered. A sense of beat occurs, as mentioned, when one can hear regular emphasis or stress in the rhythm. Such stress often encourages sympathetic physical movement, and “toe-tapping” rhythms are popular around the world.

When these pulses are organized into recurring patterns of weak and strong beats (i.e., some beats are stressed more than others), the phenomenon of meter arises. This term has been borrowed from poetry, where a similar phenomenon occurs. Take, for example, the popular rhyme “Jack and Jill went up the hill to fetch a pail of wat-er.” The syllables in bold note recurrent stresses in a regular pattern, that is, on every other syllable. These regular stresses give a sense of meter to the poem. In notated Western music, one such unit of meter is called a bar, or measure.

There are many kinds of metrical rhythm, but the most common ones are based on two’s and three’s. For instance, marches are always composed in groupings of two, also known as duple meter: ONE-two, ONE-two, or ONE-two-THREE-four. This is because the march’s primary purpose has been to accompany and regulate the movements of soldiers in the field or on parade. Human beings with two legs move in binary ways, which suggest duple meter (see Listening Ex. 7.4, 0:00-1:00). Fortunately, our range of motion is not quite so limited. The waltz is a very elegant dance that exhibits triple meter, and one that humans imitate through motion: ONE-Two-three, ONE-Two-three, etc. The waltz, with features three beats per measure, emphasizes the first beat strongly, the second less so, and the third weakly (see Listening Ex. 3.3, 0:00-1:00). Another type of meter is called compound because its metrical stresses take place on multiple levels. In compound duple, for instance, there are two (or four) primary pulses, but each pulse is subdivided into three subordinate beats (see Listening Ex. 4.1, 0:00-1:00). Compound triple exhibits three pulses at both levels. Some pieces in compound meter may also be written in aggregate segments, for instance 3 beats followed by 2, or more complicated groupings (3 + 3 +2, etc.), such as the rhythm discussed below.

Exercise Appendix.2: Meter. Listen to Listening Ex. 5.4 from the beginning, and see if you can identify the meter, i.e., is it duple, triple, or compound duple? Choose a few other assigned examples from the text and analyze their metrical structure as well.

Any musical composition can use none or all of these, or it may alternate various meters. Hispanic music very often alternates compound duple meter with triple meter, a type of rhythm called hemiola (in Spanish, sesquiaáltera): ONE-two-three, ONE-two-three/ONE-two, ONE-two, ONE-two/ ONE-two-three, ONE-two-three/ONE-two, ONE-two, ONE-two (see Listening Ex. 3.4, 0:00-0:56). A classic example of this device is the number “America” from the musical West Side Story by Leonard Bernstein (text by Stephen Sondheim). He employs the rhythm as a kind of musical marker to identify the Puerto Ricans who sing and dance it. Hemiola also occurs when compound duple meter is juxtaposed against triple meter (see Musical Ex. 7.1).

The juxtaposition of two or more different meters in a piece of music is called polymeter, and the foregoing example (Musical Ex. 7.1) is a perfect case of it. Polyrhythms result from the juxtaposition of two or more different rhythmic patterns, even though all the parts may be in the same meter (see Musical Ex. 6.1). Polymeters and polyrhythms are very characteristic of Afro-Latin music in general, especially in Cuba and Brazil, being derived as they are from West African music, in which this kind of rhythm predominates (see the discussion of West African music in chapter 5).

A rhythmic (and/or melodic) pattern that is repeated over and over is called an ostinato, the Italian word for “obstinate” (see Musical Ex. 6.4 and Listening Ex. 5.2, 0:00-0:27). This technique appears frequently in Latin American music with an indigenous or African character, as they often incorporate looped rhythms or melodies of various sorts as a basis for improvisation and dance.

When music emphasizes musical pulses between beats (upbeats) that are normally weak, one creates syncopation. This device is especially characteristic of African- derived music (see Listening Ex. 6.6, 1:19-1:30). In fact, it is absolutely central to jazz, because it lends “swing” to the rhythm. In similar fashion, rock relies heavily on syncopation to give it its characteristic motion. Rock is almost always in duple meter, four beats per bar. Normally in such a situation, the first and third beats of the measure would be emphasized: ONE-two-THREE-four. But in rock, the pattern works like this: one-TWO-three-FOUR. This pattern, also called a backbeat, is articulated in the drum set, while the melody usually hews to the meter in a more conventional way. The resulting rhythmic contrasts and interactions give rock its infectious beat (see Musical Ex. 8.2 and Listening Ex. 10.2, 0:00-1:15).

Regardless of how many beats there are or how they are accentuated, tempo (Italian for “time”) refers to how rapidly the beats are moving. Performing a particular piece at a slow tempo will yield a much different effect from a performance of the same work at a faster tempo. No other parameter of the music changes, yet it may sound altogether like a different work. For instance, think of any song you enjoy and imagine it at different tempos. A march in particular will sound ridiculous if played either too slowly or too fast. There is a rather narrow range of march tempos that will produce a satisfying effect, for instance, somewhere around 120 beats per minute, or 2 per second. Often a composer will specify the precise tempo in terms of beats per minute, which can be determined with a device called a metronome, suggesting a particular tempo.

Exercise Appendix.3: Tempo. Listen to Listening Ex. 3.9 (0:00-2:08 and 2:09-6:45) and try to discern any difference in tempo between the two passages. Are they slow, fast, or somewhere in between? If you can, find a metroinome and experiment with its various tempo settings, comparing them to various pieces assigned in earlier chapters.

Finally, any rhythm can be subdivided, that is, broken down into smaller parts by dividing it into two’s or three’s. For instance, two normal beats, ONE-two, can be divided by two to become ONE-&-two-&, that is, each beat consists of a downbeat followed by an upbeat; another subdivision by two can be expressed as ONE-e-&-ah-two-e-&-ah. Dotted rhythms represent not a division but rather an addition to a note of one half its value. The Cuban habanera features a prominent dotted rhythm that can be expressed by saying aloud only the first and last syllable of the following pattern: ONE-e-&-ah. This pattern becomes a kind of ostinato in the habanera and is one of this song’s distinguishing traits (see Fig. 2.6 and Listening Ex. 2.12, 0:00-0:39). It is very similar to the syncopated beat of a much more recent and familiar style of music called reggaetón. You can see this rhythm in Mus. Ex. 5.7 and Listening Ex. 10.1). Try tapping it out against a basic pulse, as in the transcription, to get a feeling for how syncopation works.

It is quite possible to have a musical composition without a melody, but never without rhythm. As soon as you make a single sound intended as music, rhythm occurs. Nonetheless, most styles of music depend heavily on melody to convey emotion and meaning. All songs, for instance, rely on melody as well as text for this purpose. Whereas one could easily organize a work utilizing only unpitched sound, melody requires pitches.

The best way to understand the concept of melody is to make analogies to speech. A melody is essentially a succession of single pitches forming a musical sentence, a complete musical idea that has an identifiable beginning and ending. A melody may be preceded and followed by other kinds of music, and other music may be going on at the same time, but it can stand alone as a recognizable and coherent statement. And, like any sentence, a melody can be broken down into constituent parts. A phrase is like the musical version of a clause in a sentence. Western melodies are typically made up of two or more phrases, even as this sentence is made up of two clauses. The smallest subdivision of a melody, however, is not the phrase but the motive. Motives are short musical ideas, consisting of two to five notes, which give a melody its distinctive character. A motive is very much like a phrase in language. Many well-known songs are made up of two- or four-bar phrases, to make for a very logical structure. Think, for example, of the U.S. national anthem, “The Star-spangled Banner.” Its melodic structure is very symmetrically laid out in four-bar phrases. The opening three-note motive gives it a distinctive and immediately recognizable character.

Of course, the concept of melody is common to almost all music cultures. Yet, the way melody is structured may or may not resemble what was described above. Just as different languages have their own syntax and sentence structure, so different musics can exhibit unique ways of organizing melody. For example, the melodies sung by the Kayapó-Xikrin Indians of the Amazon, treated in Cristina Magaldi’s chapter on Brazil (see Listening Ex. 6.1, 0:00-1:00), does not resemble the melodies people commonly sing in the United States, especially since the distinction between speaking and singing is not always clear in their songs.

Exercise Appendix.4: Melodic Styles. Listen to Listening Ex. 3.1, 4.5, and 5.12. Compare the melodies in terms of their structure and even their vocal production.

A composer or performer uses a series of notes called a scale on which to base a piece of music. The composer or improviser is not limited to the notes in a particular scale but will rely on them more than any others to give the piece a sense of unity and coherence. The notes of a scale are sometimes called degrees, as in the “third degree” of a scale, meaning the third note up from the first. The greater the distance between degrees of the scale, the larger the interval.

Most but not all scales span an octave. In the European tradition (and, by extension, much Latin American music), scales of many types have appeared, but the two most common scales are called major and minor. As their names imply, many in Europe and the United States associate the major scale with a bright, happy quality, while describing the minor scale as sad and brooding. However, these are culture-specific associations. In Latin America, minor scales appear much more frequently in traditional and popular repertoire than in the United States, and the key does not necessarily seem sad to listeners.

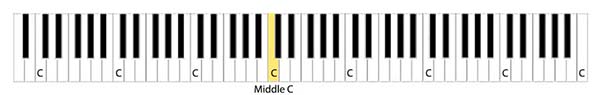

A minor scale can be created by playing a major scale beginning on the sixth degree and continuing upwards for an octave. Because certain keys are related in this way, one speaks of relative major and relative minor scales, e.g., C major is the relative major of A minor, and vice versa, because to get an A minor scale, you play on the white keys of the piano starting on A, not C.

Exercise Appendix.5: Major and Minor. Listen to Listening Ex. 8.3 (0:24-1:06) for changes between major and minor keys.

Major and minor scales consist of a series of tones either a whole step or a half step apart. A whole step is equivalent to moving from one white key to another on a piano, provided there is a black key between them. The distance from a white key to an adjacent black key is a half step. On the piano, half steps occur between white keys in only two places, E-F and B-C. It is a particular sequence of whole and half steps that gives any scale its characteristic quality, although scales are not limited to whole and half steps and may have larger or smaller gaps between notes. For instance, in other music cultures the steps themselves may be larger or smaller; intervals smaller than a half step are called microtones, and they figure prominently in music of Amerindians in the Amazon region (see Listening Ex. 6.1, 0:01-0:59).

It should be obvious by now that there are many other scale possibilities than these. In fact, there are hundreds of other possibilities. For the Western system is not a universal standard: scales can have a variable number of notes in them, with different kinds of steps arranged in a myriad of sequential patterns.

Fortunately, there are only a few other scale types that appear in most of the examples throughout this textbook. One is the chromatic scale, consisting entirely of half steps, i.e., all the keys on the piano (a scale consisting entirely of whole steps is called a whole-tone scale). Chromos is the Greek word for color, and as the name suggests, this kind of scale can have a colorful quality (see Listening Ex. 5.9, 0:00-1:30). One other scale type that is of crucial importance in Andean music in particular is the so-called pentatonic scale. The five notes of this scale can be rendered by simply playing the black keys of a piano. There are no half steps in many pentatonic scales, such as those found in traditional Andean music; instead, they consist entirely of whole steps or even larger intervals (see Listening Ex. 8.2, 0:08-0:36).

You have noticed the use of capital letters to refer to particular notes. This is a Western convention dating back hundreds of years. Rather than run through the entire alphabet, however, early on people decided it would be easier to use the first seven letters of the alphabet and then repeat them after reaching the octave: C, D, E, F, G. A, B, C. Half steps between these notes are indicated by using sharp (#) and flat (b) signs, called accidentals. For instance, an F# or a Gb both refer to the same note halfway between F and G.

In the Western system of musical notation, notes are represented as ovals (white and black) on a series of five parallel lines called a staff (pl. staves). The music for an ensemble of any size contains several staves and is called a score. A clef sign indicates which line corresponds to which note. A G (or treble) clef is in the shape of the letter G and circles the second line from the bottom of the staff, indicating that it is G. It is used to notate higher pitches, typically above middle C on the piano. An F (or bass) clef or a C clef is similarly a stylized version of the letter and indicates those respective pitches on the staff. It is used to notate lower pitches (see Musical Ex. 8.2).

Notating pitch is much easier than notating rhythm, simply because there are so many more possible rhythms than pitches in the Western system. A system of stems, flags, dots, and beams gradually developed to indicate the relative durations of the oval notes on the page. Basic durations are indicated as fractional subdivisions of the whole note (a large goose-egg shape): half, quarter, sixteenth, thirty-second, and sixty-fourth (subdivisions beyond this one are possible but rare). Time signatures appear as a fractional number at the beginning of a piece to indicate what meter the piece is in, e.g., 2/4 or 4/4 (duple meter), 3/4 (triple meter), 6/8 or 12/8 (compound duple), 9/8 (compound triple), and so on. The numerator refers to the number of beats in a measure, and the demoninator designates what type of note (e.g., quarter or eighth) gets one beat.

The key, or tonality, of a piece is determined by two things: the scale type that predominates in the composition, and the note on which that scale begins. A piece in C major is based principally on a major scale beginning on C, without any flats or sharps. A piece in D major has sharps on F and C; however, instead of writing these out on every note, it has been found more convenient to indicate them once, at the beginning of each line of music, in a key signature. The number of flats or sharps in the key signature will indicate what key the piece is in, depending on what the starting note of the scale is (see Musical Ex. 8.2). It is possible to have two or more keys occurring at the same time, something called polytonality (see Listening Ex. 7.9, 0:00-1:02). Scales and keys are the basis for the vertical dimension of musical sound, called harmony.

Up to this point, the discussion has focused on notes in a horizontal sequence, happening one at a time. However, most of the music in this text features two or more notes occurring simultaneously. This vertical dimension of music is called harmony. Harmony refers to any collection of two or more different pitches sounding at the same time. Harmony is found in many music cultures around the world, and it has been especially characteristic of Western music for the past thousand years. The most common type of vertical “assemblage” of pitches is called a chord. There is almost no limit to the number of possible chords, but the most common kinds are triads, meaning that they consist of three different notes (regardless of how high or low they are or how many performers play them). The triad has been the harmonic foundation of Western music for the past 500 years, coinciding with the period of continuous European presence in the western hemisphere.

As you might already have guessed, there are different types of triads. Two basic types are crucial to our understanding of harmony. The first kind is called a major triad. In this chord, there is a root note and two notes above it. The first upper note is separated from the root by two whole steps, an interval called a major third. From C to E, for example, is a major third (C to D and D to E constituting the two whole steps). In a major triad, the interval between the two upper notes is a minor third (one and a half steps). From E to G is a minor third. So, a C-major triad consists of the notes C, E, and G, sounded anywhere on the keyboard or on any instrument or in a group of voices. A minor triad is the reverse of the major in that there is a minor third down below and a major third up above.

Generally speaking, however, major and minor chords sound pleasing and restful to our ears, or consonant. Not all chords are consonant, however, and many sound harsh and unsettled, or dissonant. There are many other kinds of dissonant chords, but notions of dissonance and consonance are highly subjective and change from one period or culture to the next. (See Listening Ex. 2.4, 0:00-0:51, for some music that is highly consonant, and Listening Ex. 9.6, 4:50-5:53, for some that is highly dissonant.)

Triads can be built on every degree of the major or minor scale. For reasons that have to do with acoustics as well aural conditioning, the first and fifth degrees of a scale, and consequently the triads built on them, are the most important in both major and minor keys. They are called tonic and dominant, respectively. The tonic chord will predominate, and it is the harmony with which a piece will usually begin and end. But the dominant triad will always be the next-most frequently used chord in a composition, as it usually “leads” or “resolves” to the tonic chord. Third in importance is the so-called sub-dominant, on the fourth degree of the scale. Roman numerals are often used to indicate these chords: I, IV, V. In most popular music, especially rock, these three chords form the substance of the piece’s harmony and are used far more than any other chords. Chords played in a predictable sequence form something called a chord progression. Much traditional and popular music is based on the chord progression I-IV-V-I (see Listening Ex. 7.1, 0:18-2:01).

Not all music has a key or traditional harmony. When the music has no tonal center and uses mostly dissonant chords, the music is called atonal (see Listening Ex. 5.9 and 9.6, which are atonal throughout). This type of music can be highly expressive, but in a disturbing and unsettling way that conveys particularly intense emotion. Indeed, there are some extreme states of feeling and experience that cannot really be expressed as effectively in any other style of music. For a piece to be atonal, it is necessary that every note in the chromatic scale receive equal emphasis in the music and that no one note be perceived as more important than any other, i.e., as a tonal center. Very often this music will also seem to lack a sense of regular pulse or meter (see Listening Ex. 5.9 and 9.6 again). This type of music is very characteristic of the post-World War Two avant-garde.

It may seem odd to refer to the texture of a piece of music, as if it had a tactile quality like a rug or paint on a canvas. In fact, some of the terminology used in music (line, color, texture) is borrowed directly from art history. Just as one can draw analogies between language and music, so one can use visual metaphors to describe what one is hearing. In many ways, one “looks” at music with his or her ears instead of eyes.

When talking about the texture of music, one is referring to the ways in which voices and instruments combine and interact melodically and harmonically. The simplest kind of texture is called monophony, in which there is a single melody without any chords or other melodies. Monophony does not refer to how many people are performing the melody. There may be one, or there may be a hundred; they may be singing and/or playing instruments. Sometimes a soloist alternates with a group in singing monophonically, a technique known as call-and-response (see Listening Ex. 5.2, 0:00-0:37). This is characteristic of West African and Afro-Latin singing.

In any case, all the word monophony indicates is that there is a single melody, nothing else. This texture is typical of Gregorian chant (see Listening Ex. 2.4, 0:00-0:07). Much Native American music exhibits a closely related texture called heterophony, in which slightly different versions of the same melody are taking place simultaneously (see Listening Ex. 6.1, 0:00-1:00, and 8.1, 0:00-1:22).

Homophony indicates the presence of chords, either by themselves or accompanying a melody (see Listening Ex. 2.3, 1:10-1:50). All the notes in the chords move in the same rhythm, hence the prefix “homo-,” suggesting uniformity. A singer accompanied by a guitar is a classic example of a homophonic texture. In fact, homophony is the characteristic texture of most popular music.

Polyphony

Polyphony is the most complex of textures because there are two or more independent melodies taking place at the same time. Polyphony appears in a wide variety of music contexts, both traditional and classical. For instance, parallel polyphony, in which different lines move together, is characteristic of much Andean music (see Listening Ex. 8.2, 0:08-2:00). The sacred music of the colonial period in Latin America was usually polyphonic in texture (except for chant). A special kind of polyphony involves the presentation of a melody, or theme, and its subsequent imitation in other voices or instruments (or “voices” on the same instrument). This is known as imitative polyphony. The most common type of imitative polyphony is the fugue (see Listening Ex. 2.6, Fugue: 0:00-1:36). In a fugue, a melody (subject) is subsequently repeated (answered) by other lines, sung and or played, entering one at a time against a countermelody.

Exercise Appendix.6: Texture. Listen to Listening Ex. 9.2 (0:00-1:04) and try to determine its texture, whether it is monophonic, homophonic, or polyphonic.

The German author Goethe once described architecture as “frozen music.” In some ways, music is a kind of architecture. All musical compositions, whether written down or not, have a structure, a way that they are put together so that they make sense. Even the apparent absence of structure is in itself a method of organizing musical sound over time. Form is one of the first things we try to perceive when listening analytically to a piece of music for the first time.

The form of a piece of music is normally classified according to the number and sequence of the various themes (melodies) presented. Each section of a piece is dominated by a particular theme, and that section is identified with a capital letter (which does not designate notes or keys). A very common form is AB, in which the initial section is followed by a contrasting theme (and key). This is called binary form (see Listening Ex. 7.4, A: 0:15; B: 0:49). If there is a return to the opening section, perhaps in a slightly varied way, this results in the form ABA, or ternary (see Listening Ex. 2.8, A: 0:24; B: 1:20; A: 2:20). This is typical of many opera arias, and of popular song. Another form, called rondo, presents a recurring section separated by contrasting themes: ABACABA (see Listening Ex. 7.10, 4:02-6:28). It is possible to have a sequence of contrasting sections without any return of previously stated ideas: ABC (or AABBCC) (see Listening Ex. 8.2, A: 0:08; B: 0:22; C: 0:36).

As mentioned previously, the formal structures of much traditional indigenous and Afro-descendant music do not fall easily into such categories. Often its formal structure derives from cyclic, open-ended rhythmic or melodic patterns that are repeated many times in variation as a complement to dance, religious worship, or some other activity. This sort of expression must be analyzed not in terms of discrete sectional shifts, but rather in terms of subtle changes to the texture, the addition or elimination of melodies, rhythms, or other elements, the incorporation of improvisatory passages, changes in tempo or intensity in relation to other sections. In short, there are many different types of form.

Song form represents a special case because of the close relationship of the music to the text. Most song texts are poetic and consist of two or more stanzas. If each succeeding stanza (or strophe) is set to the same music as the first, the form of the song is strophic. Most traditional songs, anthems, carols, and other popular songs are strophic in form. Many vocal works consist of a verse and refrain. The verse presents new text while the refrain repeats the same text and music. In Spanish, their names are copla and estribillo, respectively (see Listening Ex. 3.7, copla: 0:27-1:19; estribillo: 1:20-1:43).

The various kinds of music treated in this text reflect the diverse cultural heritage of Latin America, including indigenous, mestizo, Afro-Latin, and European elements. These often determine the salient features that a particular piece of music exhibits. Listen to the following four excerpts, each representing one of these facets of Latin American heritage. Apply the terms and concepts introduced in this chapter when listening to them. Notice the vocal production and instrumentation (if any), rhythm, melodic structure, harmony, form, and texture of each piece. Then make your own listening guide for each based on what you perceive as you listen.

Indigenous: Listening Ex. 8.1: Harawi

In this example, take specific note of how is the sound organized

While this example from the Andes features only singing, various percussion and wind instruments are often used in indigenous music. These include trumpets and flutes made of various materials (bamboo, wood, metal, terra cotta), as well as membranophones and idiophones of assorted kinds and sizes. String instruments introduced by Europeans have been adapted to suit local tastes, as in the case of the Andean charango, a small guitar (see Fig. 8.7), and the harp. A prominent scale in Andean music is the pentatonic scale. Different forms appear, but they usually involve varied repetition of melodies, which have a variable number of phrases and motives but follow the text closely. Finally, the music is part of an oral tradition and not written down. The musicians require not only a keen sense of pitch and rhythm but also excellent memories.

Mestizo: Listening Ex. 3.2: Son jarocho group playing La bruja

In this example, see if you can identify the elements that make this mestizo. Here are some questions to ask:

Mestizo refers to a blending of native and Spanish ancestry, and the resulting hybrid forms of culture. The previous example discussed indigenous elements by contrast, European and Spanish-derived elements are conspicuous in this one. Among the most obvious is the use of a European language, Spanish, as well as related poetic forms. The structure of the music conforms to that of the poetry, in this case a copla/estribillo form with paired four-line stanzas. In any event, the purpose of the music is to complement and intensify the song lyrics, not compete with or obscure them. A popular instrument found in much mestizo music is the guitar, which originally came from Spain. It is light, portable, relatively inexpensive, and musically versatile. It can play chords and/or melodies, in either accompanying or playing solo. Yet, this piece utilizes regional variants of the guitar called the jarana and requinto, which are Mexican and not Spanish. Another popular string instrument is the harp. In terms of rhythm, though there is frequent syncopation, there is also a strong sense of pulse, in which certain meters prevail, especially duple and triple. Songs and instrumental music utilize major and minor scales, and the texture is often homophonic, with a melody and chordal accompaniment.

The characteristics of mestizo music change from one region to the next, because of the wide variety of mixtures occurring between local and Spanish traditions. In Paraguay, a style of music may be mestizo because of the prominence of string instruments, like the harp and guitar; in northern Mexico, the accordion may signal the “mestizoness” of the music. In Peru, a song’s use of lyrics blending Spanish and Quechua may mark it as mestizo; in Panama, it may be the combination of Spanish-style paseo and zapateo dance steps with local costumes. In other words, the mestizo aesthetic features local adaptations of a Spanish-derived heritage. The local flavor is evident in the creation of new kinds of instruments, dance steps, costumes, and ceremonial contexts blending Spanish and indigenous beliefs and rituals. The possibilities are truly endless.

Afro-Latin: Listening Ex. 6.6: Escola de samba (pedindo passagem)

Afro-Latin music possesses distinctive traits that distinguish it from other styles. Address the following points in your listening:

Afro-Latin music like the batucada usually demonstrates a high level of “rhythmic density” or polyrhythm, with many different beats sounding simultaneously. Pieces may be in duple or triple meter, or they may involve simultaneous rhythms that emphasize both groupings of two and three. The relationship between rhythms is very important because many performers of traditional percussion music do not read Western notation and therefore orient themselves solely on the basis of how their part fits in with the others. Moreover, many of the individual rhythms fit together to form aggregate melodies. That is to say that each performer will play certain notes of the melody, which can only be heard in its entirety when the various parts of it interlock. Thus, multiple parts seem to form a single pattern.

In terms of form, much West African and Afro-Brazilian music is based on repeating cycles and patterns, resulting in an open-ended form that lasts as long as the performance event requires. There is often a hierarchy of instruments in African-influenced repertoire, with some instruments like the bell playing a basically static, unchanging line that serves to keep the pulse. Others vary their parts a bit more, while still others feature prominently as solo instruments, fighting the relatively constant rhythms laid down by the rest. Call-and-response singing is an African-derived characteristic in much of this repertoire, featuring a soloist alternating with the group. Finally, much Afro-Latin music incorporates a vast array of sounds from metal, wood, animal skin, and plant material, giving the music a colorful abundance of timbres.

European: Listening Ex. 9.6: Mario Davidovsky, Synchronisms No. 10 for guitar and electronic sounds.

This work is quite unlike the other three examples, especially in its use of electronic technology along with a performer. It is also different in other important respects.

In addition to a wide variety of string instruments, the Europeans introduced keyboard instruments, along with many new wind and percussion instruments. In the twentieth century, electronic instruments became prominent. The textures of European music include monophony, homophony, and polyphony, especially imitative polyphony. The harmonic language is basically tonal, utilizing major and minor scales, but over time, the music has become increasingly chromatic, with the actual breakdown of tonality in the twentieth century. This tendency towards innovation and stylistic change over time (which is not the same as progress) is characteristic. The rhythm of European music is basically downbeat oriented and relies on duple, triple, and compound meters. Here, too, the quest for rhythmic novelty eventually produced increasingly complex rhythms and metrical patterns, and even the abandonment of any beat sense whatsoever (ametricality). Electronic technology, atonality, and ametricality are defining traits of Davidovsky’s work.

Though these four categories do no exhaust all the possibilities, they still represent the great diversity of Latin American music in its various cultural contexts. It is important to remember, however, that these are not impermeable categories. Rather, it is quite possible to form hybrids and cross boundaries. In fact, each of them is the result of earlier such mixtures, and that process of hybridization will persist and intensify.