This chapter focuses on the vibrant musical traditions of Argentina, the second largest country south of the U.S. border, along with the musical practices of Uruguay and Paraguay, two smaller Latin American nations. Together these three countries belong to the rioplatense region—an area named after the Río de la Plata, an extensive waterway that begins in Paraguay and Uruguay and runs southward along the Argentine and Uruguayan borders into the Atlantic Ocean. The Río de la Plata is the widest river in the world, and on its northern and southern banks lie the cosmopolitan capitals of Montevideo, Uruguay, and Buenos Aires, Argentina. Musically, the rioplatense nations lay claim to a remarkable range of expressive forms and practices. The tango, which arose in the capital cities of Argentina and Uruguay, has captivated listeners throughout the world. Other local genres—the milonga, candombe, and chacarera, coupled with a wide array of commercial styles and classical idioms—contribute to the dynamic musical landscape.

Together, Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay occupy an imposing physical space of approximately 1.3 million square miles—a territory larger than the combined total sizes of Mexico, California, Arizona, and Texas. Yet, even though the rioplatense region encompasses a large and imposing landmass, it has a relatively small population. Today, Argentina has only 46 million people (according to the 2021 census). Compared to the two other territorially largest countries in Latin America Latin America—Brazil (population 202 million ) and Mexico (population 117 million)—it remains an underpopulated nation. Yet, it is precisely this sparse rate of settlement within a proportionately large landmass that defines key characteristics of the rioplatense population.

A Brief History

Compared to other parts of Latin America, the rioplatense nations were slow to develop. A relatively sparse population of indigenous groups originally settled in the region. Their numbers declined rapidly upon the arrival of the Spaniards, who expelled, obliterated, and assimilated a large number of native communities. Other indigenous groups fell prey to European diseases. Today, Uruguay lacks a statistically sizable indigenous population. In contemporary Argentina, less than 3 percent of the people belong to Amerindian groups, which have been forced into a marginalized existence along remote border regions. Paraguay differs from other rioplatense nations in that European settlement initially took hold in the eastern half of the country, which was inhabited by indigenous groups who spoke the native language, Guaraní. The Spaniards quickly subjugated and assimilated this group, giving rise to a predominantly mestizo (mixed-race) population. Today, the Paraguayan government recognizes both Guaraní and Spanish as official languages, but the original practices of preconquest groups remain outside the cultural mainstream.

European settlers moved slowly into the rioplatense region, which lacked the rich material resources of other areas such as Mexico and Peru. Yet, once faced with the threat of a Portuguese invasion (via Brazil), the Spaniards established a stronghold there. In 1776, they founded the Viceroyalty of La Plata, which included the present-day countries of Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay, as well as parts of southern Bolivia. The Viceroyal capital, Buenos Aires, exercised an imposing degree of power, controlling access to both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Yet, after 1816, when the Viceroyalty declared independence, Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia, and Uruguay formed as separate nations. These new countries faced similar dilemmas as they aimed to establish distinctive identities and differentiate themselves from Spain. Ultimately, the way that rioplatense nations used their music to define, contest, and negotiate their changing identities offers fundamental insights into our knowledge of the region.

The rioplatense area had a less pronounced West African cultural presence than many other parts of Latin America. During the Colonial period, both Montevideo and Buenos Aires emerged as major slave ports and absorbed thousands of Africans arriving into the New World. However, during the nineteenth century, a disproportionate number of slaves were forced into military service, where they lost their lives fighting for South American independence and in the following civil wars. In 1871, a yellow fever epidemic struck the southern barrios of Buenos Aires and had a devastating effect on the Afro-Argentine population there. Tragically, few traces of this community survive today, although in Montevideo and the surrounding areas an important Afro-Uruguayan presence remains. In Paraguay, a small but significant community of African descent emerged during the 1820s, when José Gervasio Artigas, the founder of Uruguayan independence, was forced into exile near Asunción and brought a company of Afro-Uruguayans troops with him. Today, as Afro-Paraguayans struggle against marginalization and aim to win back territories that the government has seized from them, they have received infusions of cultural support from Afro-Uruguayan communities in Montevideo.

As a whole, Argentina and Uruguay are considered two of the most Europeanized Latin American nations. This characteristic dates back to the time of Spanish settlement and was reinforced during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when millions of immigrants from Italy and Spain, as well as from France, Britain, Germany, Russia, and Eastern Europe, arrived on rioplatense shores—a tendency that coincided with immigration to Ellis Island in the United States. Around 1900, first-generation Europeans made up over one-third of the total Uruguayan and Argentine population. In large cities, this figure rose higher—to around 50 percent. This influx of new settlement had a pronounced impact on local expressive forms, not the least of which was music. As we shall see, two of the most significant rioplatense genres—tango and opera—received their impetus from Italian immigrants and the strong cultural imprint they left upon the region. Thus, immigration and its impact on local musics form another central theme of this chapter.

Panorama of Argentine Music

Argentina can be divided into seven areas, each with its own landscape and musical features (Figure 7.03). The pampas are a fertile farming and grazing region. The tremendous livestock and agricultural industries of this area have fortified the Argentine economy. This territory also holds great political sway because it includes the large and powerful capital of Buenos Aires, whose supremacy Argentines have challenged but have never successfully replaced. From Buenos Aires and the pampas come the tango, milonga, and many recent forms of urban popular music.

The litoral (littoral), to the northeast, occupies the space between the Paraná and Uruguay rivers. It is characterized by social dances of European origin and the use of the accordion, transplanted by immigrants. Further to the north is the subtropical Chaco, with its indigenous populations and cultural links to Paraguay. The central Argentine region, settled early during the Colonial period, is known for its Hispanic influences and is home to the chacarera, examined later in the chapter. The western area of Cuyo musically resembles that of nearby central Chile. Likewise, the northwestern Argentine territory has close cultural ties to surrounding Andean communities. As migrants from this region in search of better opportunities moved into Buenos Aires, their music gave rise to an incipient Andean folk revival movement, discussed in Chapter 8. Finally, the remote Patagonian area, extending to the tip of South America, remains sparsely inhabited. There the Mapuche tribe forms an important part of the local Argentine population, and this community has an even greater cultural presence in Chile.

In Argentina, scholars tend to classify traditional music into two categories. They use the term indígena (indigenous) to describe musical repertoires that predated the arrival of the Spaniards and that preserved preconquest languages, instruments, and practices. They apply the term criollo (creole) to music that uses the Spanish language and has a predominance of European features. Generally, throughout Latin America, the term criollo denotes traditions descended from European roots, while the term mestizo refers to blended cultural characteristics. However, in Argentina—a country profoundly shaped by European immigration—the term criollo also refers to the absorption and inclusion of indigenous elements within the mainstream population.

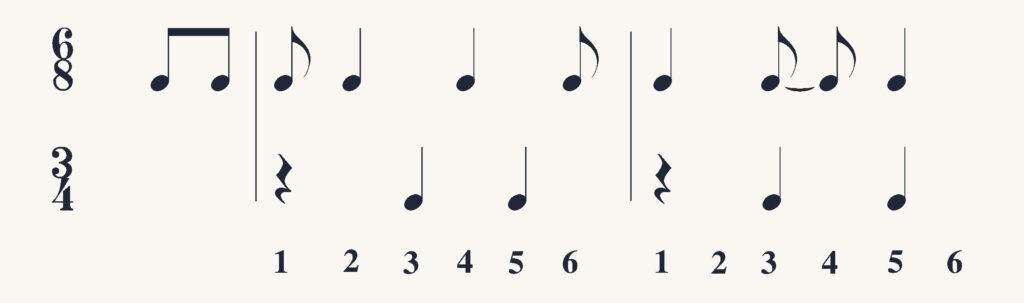

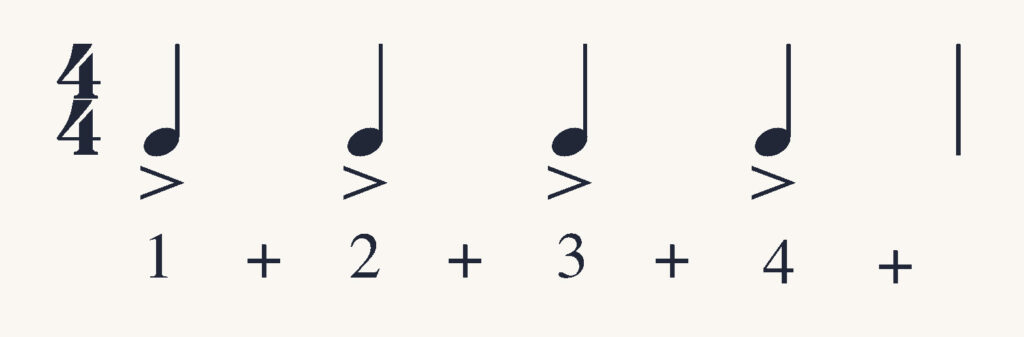

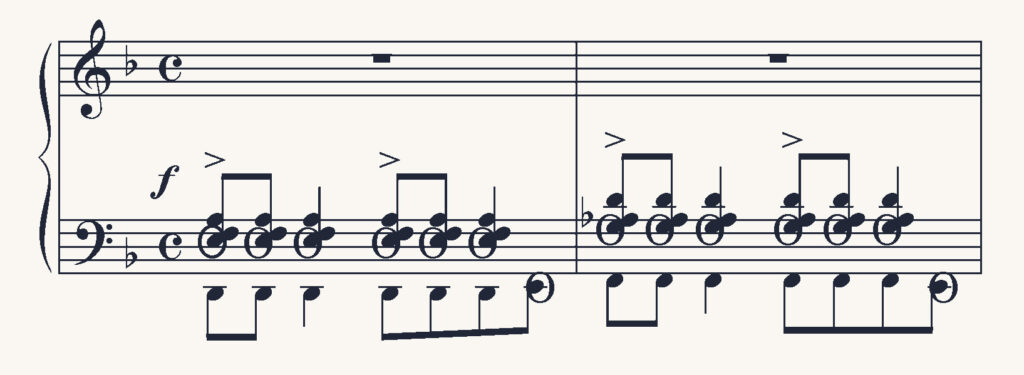

Common cultural and musical features extend across Argentine regional borders. One central characteristic is the criollo tradition in which Hispanic influences prevail. As in other Iberian-based repertoires, dance rhythms frequently center on the interplay between triple 3/4 and compound duple 6/8 meters, resulting in hemiola. One common pattern found in Argentine social dances such as the zamba, chacarera, and gato appears In Example 7.1. The first full measure of the upper part (representing the melody) is in 6/8 time, with accents on the first and fourth eighth notes. These accents divide the six-beat pattern into two parts. The second measure emphasizes the first, third, and fifth eighth notes dividing the beat patterns into threes. This alternation between twos and threes creates hemiola from one measure to the next. At the same time, the accompaniment (shown in the lower part) implies triple meter, creating hemiola against the melodic part in the first measure. Try clapping and counting this pattern aloud with a classmate. Feel the rhythm pulling apart and coming back together again. This sense of convergence and divergence, of musical fission and fusion, gives Argentine music its compelling dance rhythms.

Criollo songs have a nostalgic and sentimental flavor. They tend toward slow tempos and non accented rhythms that ebb and flow freely along with the text. This expressive style differs markedly from criollo dance music and establishes a sharp contrast between local styles of singing and dancing. This duality extends beyond the traditional repertoire and encompasses other styles of Argentine music. For example, Astor Piazzolla’s La Camorra I illustrates these powerful expressive contrasts by juxtaposing nostalgic songlike sections with brilliant technical passages derived from the raw intensity of Argentine dance (see Astor Piazzolla, La Camorra I, Listening Guide 7.5). Melodically, most criollo music is based on European major or minor scales. Some pieces from the North or Northwest employ tritonic (three-note) or pentatonic (five-note) scale systems. Other examples fluctuate between major and minor keys. A large number of Argentine melodies use regular phrases and descending melodic lines. The traditional criollo repertoire relies largely on European harmonies, especially tonic, subdominant, and dominant triads (I, IV, and V) of major and minor keys. Usually, the music follows patterned harmonic progressions, with regular chord changes every one or two measures. The principal type of texture consists of accompanied melody. Frequently, the highest voice sings the main musical idea, and a second part harmonizes three or six notes below it. This vocal style, known as singing in parallel thirds and sixths, is widespread throughout the world and has its roots in Iberian practices

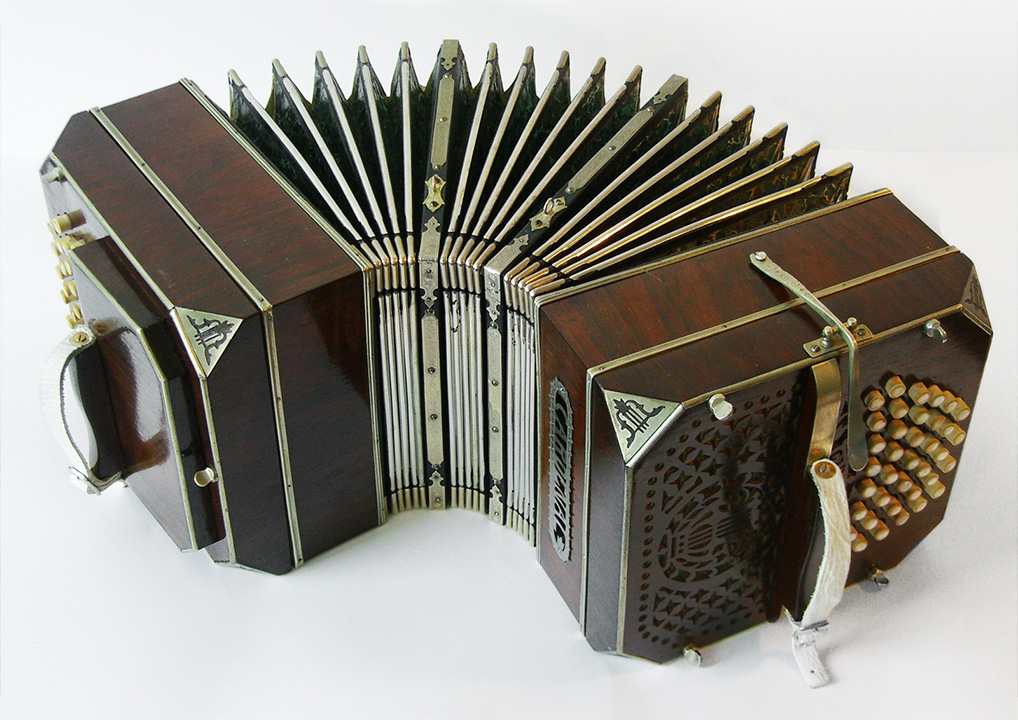

Traditional Argentine instruments include the violin, guitar, accordion, and bombo (large double-headed drum played with sticks). The bandoneón, an accordion-like instrument of German origin, arose in conjunction with the tango, but is also used in traditional ensembles throughout Argentina. Above all, the guitar is the preferred criollo instrument. Originally acquired from the Spaniards, it developed in various sizes and shapes throughout the rioplatense region. Today, the standard six-string instrument prevails. It is the national instrument of Argentina.

Criollo poetic forms also derive from Spanish traditions. Frequent subjects include patriotism, heroism, philosophy, and humor. One important group of poetic texts (found especially in vidalitas and milongas) focuses on emotional extremes. These poems mourn personal tragedies, dwell on thoughts of suicide and death, and convey a sense of hopelessness. When Argentine musicians perform such lyrics in an expressive criollo style (using slow tempos, free rhythms, minor scales, and descending contours), their sense of melancholy increases. Even as outsiders to the culture, we can identify with these sentiments because the same elements connote sadness in our own music, which likewise stems from European traditions. To get an idea of this expressive vocal style, listen to Alfredo Zitarrosa’s “Milonga para una niña” (Listening Guide 7.2), examined in detail later in the chapter.

Most Argentine rural dances involve one or two non-embracing couples. Choreographic gestures include handkerchief-waving, finger- snapping, and handclapping, along with an agile foot-tapping motion known as zapateo. Some criollo dances derive from the principle of cambio de sitio (change of place). They consist of two complementary sections. In the first, primera, the dancers end in opposite positions; in the second, segunda, they come back to their original places. These two sections create a sense of symmetry that derives from Iberian roots and that forms the basis of Argentine criollo dance.

Let us now take a more detailed look at a specific Argentine region. The pampas offer an excellent point of orientation as the geographic, economic, and political nucleus of the nation. A central folk figure is the gaucho, who works with native cattle and horses. The gaucho, who arose as a male mestizo, dates back to the colonial period, and his ethnic roots reflect the blending of Spanish, indigenous, and African populations. Yet, this figure was also recognized as a criollo because of the perceived dominance of his Hispanic heritage. More than a racial category, however, the gaucho is defined by his way of life. His existence centered around horses, which allowed for mobility across the plains; his cattle offered a steady food supply and provided a source of income. The gaucho lived off the land in a simple thatch and mud hut. He ate a diet of roasted beef cooked over an open flame that was accompanied by little other than mate, a highly caffeinated herbal tea that people from the rioplatense region still drink today. The gaucho worked at difficult and dangerous tasks— breaking horses, rounding up cattle, and managing livestock on commercial ranches known as estancias. Rugged masculinity and competition characterized his work and typified his music.

A related figure of the pampas was the payador, a gaucho singer and guitarist who performed, composed, and improvised music. In rural fiestas and pulperías (local bars and stores), he played music for his own enjoyment, provided an accompaniment for dancing, and competed in improvised song contests known as payadas (which paralleled the Cuban controversia and Brazilian cantoria described in Chapters 5 and 6). Payadas involved two or more gauchos who performed improvised stanzas in ferocious contests of wits. In these spirited duels, gauchos hurled difficult questions and daring remarks at their opponents at the same time that they dodged the challenges leveled at them. They were expected to think quickly, maintain the speed of the music, and avoid hesitations that revealed signs of weaknesses. The contests lasted for hours until one of the gauchos was exhausted, defeated, or overwhelmed by the cries of the spirited crowd in attendance. Today, rioplatense musicians perform payadas competitively in folkloric festivals. National Payador Day takes place on July 23 in Argentina and August 24 in Uruguay.

Gauchos also competed in malambos (improvised dance contests). In these competitions, two male contestants took turns performing vigorous zapateo dance steps. Malambos lasted for hours until one of the dancers was exhausted or defeated. In 1871, Ventura Lynch described a malambo that lasted an entire night and consisted of 76 separate dance sequences. The malambo is accompanied by a strummed guitar accompaniment in 6/8 time. It uses simple progressions in major keys, such as the harmonies G–A–D (IV–V–I). As the malambo progresses, the guitarist improvises variations on the progression to coordinate with the dancers’ changing steps. Today malambos are taught in national dance schools and performed in Argentine festivals. Modernized versions are staged in folkloric celebrations such as the Festival Nacional del Malambo in Laborde (for which selected examples can be found on YouTube).

The example of a malambo (Listening Guide 7.1) was composed by Atahualpa Yupanqui (Héctor Roberto Chavero, 1908–1992)—a singer, poet, guitarist, and folk music collector who revived and promoted Argentine music. Yupanqui grew up in Buenos Aires Province and identified with the gaucho heritage. He composed around 1,200 pieces of folk music, and his performances show respect for the original tradition. In “Malambo,” Yupanqui revitalizes the rural gaucho dance for modern urban audiences. This piece is based on traditional malambo harmonies (note the IV–V–I progression at 0:18). Yet, the composition also incorporates nontraditional features. Although rural malambos are strummed, Yupanqui’s piece draws upon the full range of modern guitar techniques including plucking, slurs, arpeggios, muted strings, and golpes (strikes on the body of the instrument). These sounds enhance the piece for modern listeners, who experience the music outside its original context, but form a clear image of the original gaucho genre through the composer’s creative additions.

Yupanqui forms part of a larger group of Argentine performers who created original music from traditional sources and who played in professional venues such as radio, television, and folk festivals. The most famous Argentine musician who continued in this style was Mercedes Sosa (1935–2009). Sosa was born in rural Argentina in the northwest province of Tucumán. In 1965, her professional career began when she sang at the most important national folkloric festival held in Cosquín. Inspired by Yupanqui’s revival of traditional music, she championed a new Argentine song movement known as nuevo cancionero. Closely aligned with Cuban nueva trova and Chilean nueva canción (see Chapters 5 and 8), this movement combined traditional styles with left-leaning political lyrics that aimed to improve the socioeconomic conditions of poor workers. Sosa endured constant harassment during the years of the Argentine military dictatorship (1976–1983). The government arrested her during a concert in La Plata, intimidated her with death threats, and banned her music from the public media. Artistically silenced, she retreated to Europe, where she remained from 1979–1982. Upon returning to Argentina, she reached out to broader audiences by incorporating popular styles and joining forces with rock musicians in her critique of the regime. The recipient of several Latin Grammy awards, Sosa is remembered for her powerful alto voice and for her use of music to protest human rights abuses throughout Argentina and the world.

Transformation of the Pampas

Around the turn of the twentieth century, the gaucho’s traditional lifestyle changed. As Argentine leaders promoted the financially beneficial exportation of livestock, ranchers fenced the open range and selectively bred their cattle in pens. This step eliminated the legendary independence of the gaucho, who previously had enjoyed great freedom of movement across the plains. The native horsemen now had to work within a commercialized system. Those who were unable to adapt were forced into the suburbs of Buenos Aires, where they found new work in slaughterhouses and meat-salting factories. There they mingled with a new group of immigrants, who were also marginalized and displaced. In the process, some traditional customs disappeared, while others assimilated into new ways of life. Accordingly, much of the gaucho repertoire that comes down to us today survives in this hybridized state.

One type of music that transitioned from the country to the city is the milonga. Although the term “milonga” can refer to popular urban performance spaces, more often it designates a genre—one of the most representative of the pampas today. There are several types of milongas, among them the milonga pampeana, an expressive solo song. Frequently, this genre uses eight-syllable lines arranged in ten-line stanzas known as décimas (which are also heard in the Cuban controversia). Textually, some milongas evoke the disappearing rural culture of the past, while others recall events from the lives of real or imagined gauchos. A considerable number dwell on intensely melancholy sentiments, heightened by slow to moderate tempos, minor scales, and descending melodic lines—all features identified with criollo repertoires.

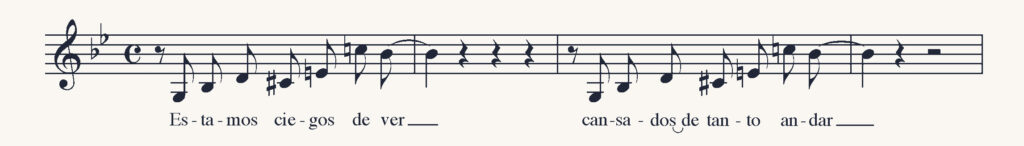

Our example of a milonga, composed by Alfredo Zitarrosa 1936–1989), comes from Uruguay, which shares a common pampean culture with Argentina. Like Yupanqui, Zitarrosa promoted the traditional music of his nation and focused specifically on the pampas. His “Milonga para una niña” uses a typical décima rhyme scheme, ABBAACCDDC. The lyrics exemplify the criollo tradition by portraying music as a release from human suffering. This piece deals with a man who cannot return the love of a young woman who adores him. He offers her a milonga as the one lasting form of joy he can give her.

To learn more about Mercedes Sosa, visit her online obituaries and explore her award- winning CDs: Acústico (Acoustic), Corazón libre (Free Heart), and Cantora 1 (Singer 1).

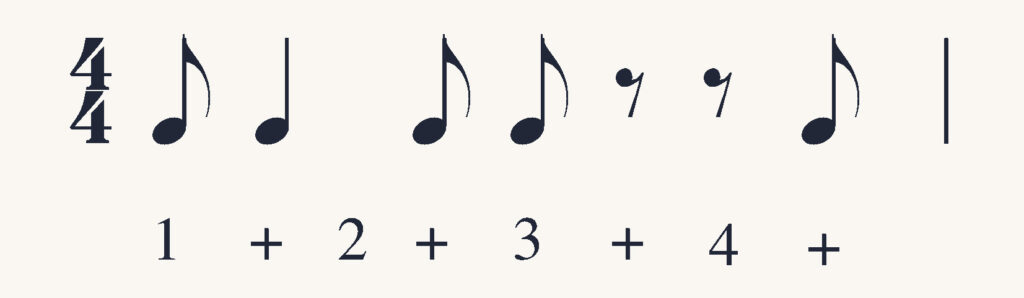

The “Milonga para una niña” begins with a guitar introduction in syncopated duple meter. Afterward, sung décimas alternate with instrumental interludes. Note how the vocal style contrasts with the rhythmically animated guitar sections. If we tried singing along with Zitarrosa, we would notice that the shape of his melody barely changes. This is because his entire range is limited to five notes of the minor scale, which makes it sound as if he is speaking the text rather than singing it. After the eighth line, Zitarrosa pauses dramatically, as guitar chords punctuate the vocal line, driving home the message of the text. Meanwhile, the melody, which lingered on the dominant (fifth note of the scale), descends to the tonic (first note of the scale) to complete the stanza.

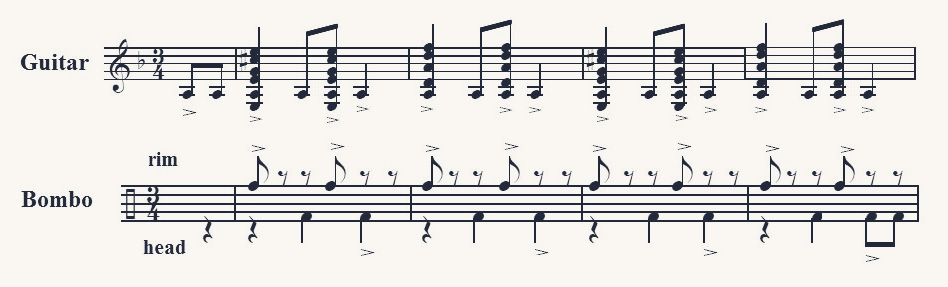

Musical practices in traditional areas, such as the central province of Santiago del Estero, have greatly enhanced Argentine cultural life. The music of this region incorporates lyrics in the indigenous language of Quechua. It emphasizes the violin within ensembles that also include the guitar and bombo. One vibrant genre associated with the region is the chacarera, a lively couples dance that is frequently performed in peñas (folkloric clubs). Rhythmically, the dance features compelling offbeat accents and shifts between 6/8 and 3/4 meters. Note how the bombo creates the characteristic hemiola associated with the dance. While the rim part accentuates beats 1 and 4 (dividing the six-count measure into two), the head part emphasizes beats 3 and 5, suggesting triple meter. The guitar reinforces these patterns. A transcription of the signature chacarera rhythm appears in Example 7.2

Today, most chacareras are sung, and their form derives from the alternation of vocal and instrumental sections. Normally, the music begins with an instrumental introduction as the singer announces the start of the first section (“la primera”). At the end of the section, t he group takes a break until the leader cues the second section (in this recording we hear him call “otra vuelt a,”meaning “one more time”). Then, the music from the first section recurs, but with a different text. The form of the chacarera appears in the diagram below.

(Form of the Chacarera diagram)

The “Chacarera del paisano” (Listening Guide 7.3), created and performed by the folk singer and violinist Sixto Palavecino (1915–2009), illustrates the traditional rhythms, instruments, and structure of the genre. Note how Palavecino represents the confrontation between the countryside and the city. The word “paisano” in his title refers to someone who comes from an Argentine village or rural area. This country-dweller recalls his trip to Buenos Aires, where he encounters the modern lifestyle of the city. Overwhelmed, frustrated, and amused, he meets city life on his own terms. The paisano uses the rural term rumbear (to make one’s way) to describe his arrival at Retiro Train Station. Later he compares the subway turnstile to the familiar “trancas de corral” (corral gates). He attributes the frightening speed of mass transit to Zupay, the Quechuan term for the Devil. This conflict between urban and rural values characterizes many Argentine expressive texts.

(Palavecino: “Chacarera del paisano” diagram)

Another traditional Argentine genre is the chamamé, which began in the littoral. This dance mixes the Czech polka, brought over by immigrants, with local criollo features. Yet, unlike the original polka, which uses duple meter, the chamamé is based on a combination of 6/8 and 3/4 time. It has a romantic character, sentimental lyrics, and is danced cheek-to-cheek. It frequently uses texts in Guaraní—an important linguistic marker of the region. The chamamé features the accordion as the main melodic instrument within an ensemble that can also include a bandoneón, two guitars, and an upright bass. Although this dance originally developed in rural areas, it achieved widespread popularity through the mass media, beginning with “Corrientes poty” (Corrientes in Bloom),” which RCA Victor recorded in 1931 in Buenos Aires.

if you liked the traditional chacarera, you might enjoy modern examples, such as the electronic “Chacarera for Argentina” by Angelini Music or the jazz fusion “Chacarera de la esperanza” (Chacarera of Hope) by the Pablo Ablanedo Octet.

The folk music of Paraguay parallels the Argentine littoral in important ways. Both traditions employ song lyrics in Guaraní and embracing couple dances. Yet, as opposed to the focus on the accordion in north-eastern Argentina, Paraguayan music emphasizes the harp. Traditionally this was a diatonic instrument, meaning that it could not play outside a given key without having to retune the strings or adjust the mechanism. Transplanted from Europe, it was modeled on the Spanish harp used to accompany liturgical music and play for court celebrations during the medieval and Renaissance periods. Initially, in the New World, the harp fulfilled a religious function. Yet as Alfredo Colman, an authority on the Paraguayan harp, points out, during the twentieth century, the government symbolically promoted the instrument to foster a sense of Paraguayan identity. Today, the harp plays a vibrant role in defining the musical culture of the nation (Figure 7.06). It functions as both a solo and ensemble instrument and can be fitted with a special lever to access the chromatic notes and perform the international repertoire.

For a documentary that traces cultural influences on the chamamé and includes vibrant performances by contemporary artists, see Argentina: Chamamé crudo (Films Media group 39528, 2007). You may also enjoy listening to recordings of Chango Spasiuk, an iconic chamamé musician who is featured in the documentary.

The most famous traditional Paraguayan harpist was Félix Pérez Cardozo (1908–1952). He established a professional standard of harp playing as well as collecting, arranging, and composing folk music for the instrument. His most popular arrangement, “Pájaro campana” (The Bell Bird), imitated birdcalls with onomatopoeic instrumental effects. In addition, the harp assumes a central role in performing traditional Paraguayan genres, the most important of which is the polca paraguaya (Paraguayan polka). Like the Argentine chamamé, the polca paraguaya features syncopated rhythms in 6/8 and 3/4time. It bears no resemblance to the European genre of the same name, which is in duple meter.

Uruguay shares important musical features with Argentina, especially the traditional pampean repertoire. Yet, one key difference revolves around the Afro-Uruguayan presence based in Montevideo. This vibrant community contributes central expressive forms that have shaped the cultural identity of the nation.

The most significant musical contribution of the Afro-Uruguayan population is candombe, which has recently received worldwide recognition from UNESCO as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. The term candombe (which differs from Brazilian candomblé) dates back to the colonial period and refers to a dramatic dance of African origin. Historically, candombe used a stock cast of symbolic characters that were believed to represent important authorities in African society. These characters included: a king, a queen, a gramillero (young dancer disguised as an old man), an escobero or escobillero (broom maker), and a mama vieja (old woman). Although this dance lost certain aspects of its original pantomime, important characters survive in performances today. Figure 7.07 illustrates several of these figures in a modern candombe performance. On the right is the gramillero, who has a false white beard, a pair of glasses, and a top hat. He walks with a cane and can be seen with a bundle of herbs, since he is portrayed as an herbalist or medicine man. On his left is his female counterpart, the mama vieja, who has a head cloth, wears a long flowing skirt, and holds a parasol. Behind the gramillero and mama vieja are two of the characteristic drums associated with the candombe tradition—the chico and piano tamboriles, which are described in detail in the following paragraph.

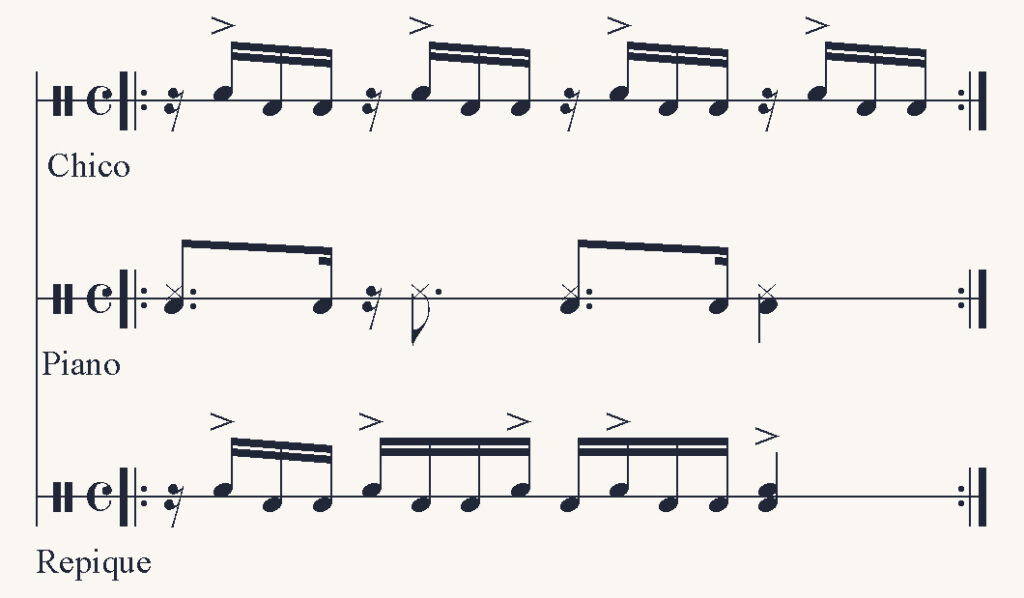

The main instrument associated with candombe is the tamboril, a single-headed drum that also appears elsewhere throughout Latin America. Musicians carry this instrument over their shoulders and play it with two hands, one of which holds a stick. Originally, four sizes of tamboriles participated in candombe. From the highest to the lowest, they were the chico, repique, piano, and bajo or bombo. Recently, the lowest part has disappeared. The three remaining instruments produce a drum call known as the llamada, which is polyrhythmic, meaning that each instrument has its own independent beat pattern. The llamada is the defining musical element of the dance.

A rhythmic transcription of a llamada is shown in Example 7.3. The notes above the line are played by the left hand and, the notes below it, by the right hand using a stick. The accent marks represent slaps, and the letters “x” on the noteheads indicate muffled strokes. Because the repique part is improvised, this example shows only one of many possible rhythms that can occur in a candombe performance. Additionally, any instrument may improvise a Caribbean clave pattern known as madera (wood) on the body of the drum at any time.

One remarkable thing about candombe is the way that the genre has reinvented itself throughout history. It began as a modest expression of a culturally vibrant but impoverished community. During the early twentieth century, the conjuntos lubolos, or societies that maintained the tradition, instituted the dance in Montevidean carnival. Within this new context, the emphasis shifted toward a commercialized style of performance in lavish parades and competitions. While certain traditional practices continued, candombe came under the influence of Brazilian carnival and added new personalities and attractions drawn from show business. Once candombe entered into a commercially mediated space, it mixed with other popular styles, upon which it juxtaposed its signature llamada rhythm. Some musicians used the guitar to replace the tamboril parts, which previously had anchored the genre throughout its many stylistic transformations. These fascinating developments raise a provocative set of questions. Is candombe still an Afro-Uruguayan form, even though it has interacted significantly with other types of music? And can it still be considered a form of traditional music, since its performers now operate within an urban popular space, where artistic decisions are mediated by commercial concerns?

To learn more about candombe, watch the DVD: Afro-Uruguayan Rhythms: Candombe (Surmenages B000gL196C, 2006). You may also enjoy listening to music by Cachila and his group, Cuareim 1080.

Other genres explored throughout the chapter touch on similar issues. Although the chacarera originally had close ties with Santiago del Estero, it has since been assimilated within a broader national repertoire, where it is taught in the public schools and performed in folkloric shows as one of many Argentine dances. Contemporary musicians have added new instruments, such as the saxophone and electric guitar, and have used the chacarera rhythm to create urban hybrid fusions. In the littoral, the chamamé has grown popular through its dissemination in the mass media, beginning with its earliest recordings produced in Buenos Aires. In Paraguay, questions about the local versus the global have led to debates about whet her musicians should chromatically alter their instruments to accommodate international repertoires. These cases raise questions about the connections between local genres and their original performance settings. These cases, which raise questions about the connections between local genres and their original performance settings, lead us to ask how performers have modified their aesthetics (that is, their ideas about how music should sound and what it should mean) when representing works to an international community. In this way, the genres we have examined can be seen as dynamic cultural fields through which musicians negotiate conflicting ideas about tradition and modernity. Although the future of such genres remains unclear, one thing is certain: rioplatense musicians have drawn upon a wide variety of regional traditions as a source of creative inspiration. They will continue to find innovative ways to celebrate their heritage in the years ahead.

The Rioplatense Tango

Among the many styles of Latin American music, the tango has fascinated au-diences throughout the world. Nostalgic, melancholy, sensual, and dramatic, it has captivated the public with its compelling rhythms and dance steps. Today, international audiences experience the tango in different ways. They attend popular stage shows and musicals; they listen to Astor Piazzolla’s recordings; they watch street musicians in the subways of Paris, Helsinki, and Tokyo; and they learn to dance the tango in nightclubs and dance studios. Most of all,for the people of Argentina and Uruguay, tango is a deeply embedded symbol of rioplatense culture.

The word “tango” is of probable African origin. It once referred to popular music and dance celebrations performed by slaves throughout the Caribbean and Atlantic coastal regions. Initially, the genre overlapped with the milonga and candombe, as well as with the Cuban habanera (see Chapter 5). By the turn of the twentieth century, however, tango emerged as an independent dance genre (around the time that the urbanized samba took hold in Brazil). The rioplatense tango arose on the outskirts of Buenos Aires and Montevideo in poverty-stricken districts known as arrabales. The compadrito, a quintessential early figure associated with the genre, emerged out of this social setting. He assumed the pose of an arrogant bully; his dress and behavior mocked the elite. The compadrito blended gaucho and immigrant characteristics. He spoke lunfardo, a dialect tinged with references to the criminal underworld that combined Italian idioms with rioplatense speech. Most people considered him vulgar and disreputable, but others secretly admired his provocative sensuality. Indeed, he was the one figure who captured the mythical space that the gaucho once held in the Argentine imagination.

Originally, the compadrito danced the tango with prostitutes in brothels. (However, due to a shortage of women in an environment dominated by young male immigrants, two men could also perform the dance.) The risqué choreography, which showed couples locked in a tight embrace, disturbed modest citizens outside the arrabal. Some construed the dance as a representation of compadrito knife fighting, or duelo criollo, while others interpreted it as an enactment of sexual intercourse itself. Eventually, the tango began to lose its stigma when professional musicians introduced it into more-reputable social spaces, such as the theater, radio, and cinema. A turning point came after 1911, when Camille de Rhynal (a Parisian dancer and choreographer) modified the steps into an elegant ballroom dance that the French aristocracy embraced. (Figure 7.8 illustrates the gentrified Parisian choreography.) Once the tango received its endorsement from France, upper-class Argentines had no choice but to accept it, since they upheld Paris as the model of cultural refinement. Technically, the tango never represented all of Argentina, as the original genre was associated with Buenos Aires. Yet, acceptance from Paris guaranteed its status as an iconic national dance.

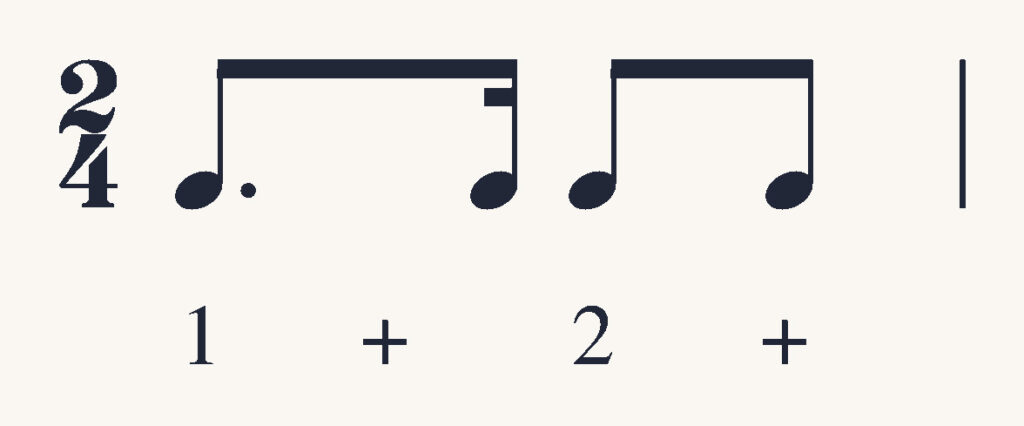

The first stage of tango history, known as La Guardia vieja (Old Guard), lasted until 1920. During this period, the tango emerged as a genre of in-strumental music based on a three-part form with different sections (ABC). Usually, Guardia vieja ensembles had four instruments: violin, flute, guitar, and bandoneón (In Depth 7.2). Arguably the most famous tango ever written, Gerardo Matos Rodríguez “La Cumparsita” (“The Little Carnival Procession”), recorded in 1917, dates from this period. Initially, early tangos used rhythms related to the habanera and milonga in duple meter (Exam-ple 7.4a). Yet, during the 1910s, bandleaders began to slow the tempo and adopt a quadruple meter with sharp accents. Two new patterns, marcato and síncopa (Examples 7.4b,c), characterized the bass line of these more recent tangos and established their harmonic and rhythmic foundations.

As the tango gained prestige, it entered into a second phase called La Guardia nueva (New Guard), which lasted from 1920–1955. People from all social classes experienced the genre on the radio, in the movies, in nightclubs, and in cafés. As the tango moved into these upscale social spaces, it underwent a rags-to-riches transformation. Because listening to the music was now just as important as dancing, a new style evolved called the tango canción (tango song). This genre emphasized the voice, which skillfully used rubato (that flexible sense of rhythmic ebb and flow) to highlight the expressive accents of the text. The instrumental accompaniment became smoother and more polished as piano and strings enhanced the ensemble, which eventually employed professional performers and arrangers. No single instrument stood out, and the bandoneón, which had once dominated the ensemble, blended seamlessly with the other instruments. The tango canción used a standardized form with two equal and balanced sections, which highlighted the new features of the genre and allowed audiences to hear them more clearly.

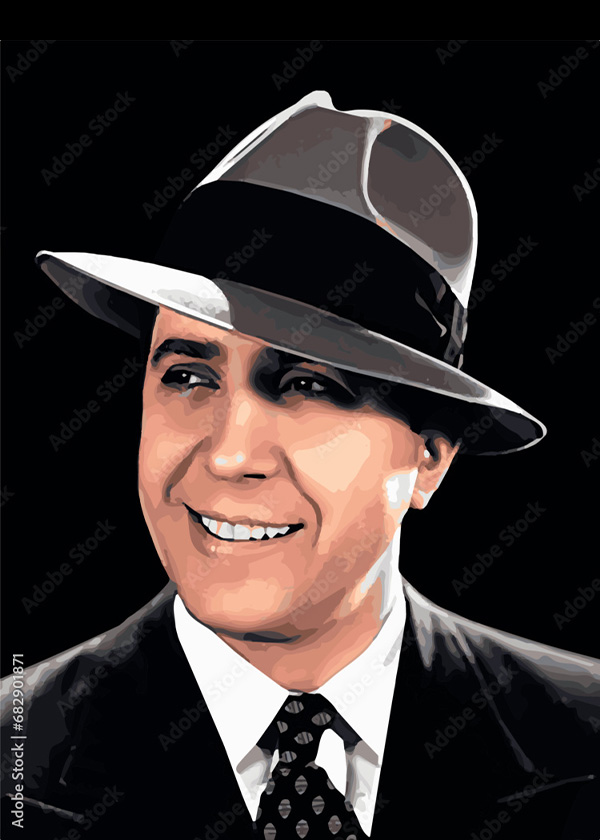

The rioplatense singer and composer, Carlos Gardel (1884?–1935) is upheld as a legendary idol in tango history. He created the earliest tango canción with his 1917 recording of” “Mi noche triste“ (My Sad Night). Gardel’s exquisite sense of delivery is still a model for tango singers.

His life is cloaked in mystery, making it difficult to differentiate the fact from the myth. According to one account, he was born the illegitimate son of a French washerwoman who immigrated to Buenos Aires. Yet, another story claimed him as the unwanted child of an Uruguayan colonial, who was adopted by his maid! Despite these uncertainties, we do know that Gardel had a remarkable voice that allowed him to break out of the arrabal and establish an international career. He moved in elite social circles,

In depth

The bandoneón once dominated the tango ensemble; its sound and style still define the genre today. Transported to Argentina by German immigrants, this instrument visually resembles the accordion. Its 38 right-hand buttons play in the up-per and middle ranges, and its 33 left-hand buttons produce the low register. Originally designed as a diatonic folk accordion that played in only a few keys, the bandoneón evolved to include more buttons, which allowed it to substitute for the organ in small German churches. Normally on keyboard instruments, neighboring tones occupy adjacent keys, but because of the haphazard way that the bandoneón evolved, its complex physical layout defied logical explanation. Fiendishly difficult to play, it has attracted a core group of performers who have built the core repertoire of the tango around this impractical (but fascinating) instrument.

befriending movie stars and appearing in motion pictures himself. Above all, Gardel convinced rioplatense immigrants that they too could achieve great success. The nation mourned Gardel when he died tragically in a plane crash over Medellín, Colombia, at the height of his career. His lifestyle and music brought legitimacy to the genre worldwide. Just as the arrabal brought gauchos and immigrants together, Gardel’s tangos combined rural and urban elements. Gardel himself personified this cultural fusion. In early performances, he dressed in gaucho clothing and sang to the accompaniment of the guitar. His songs combined the polished Guardia nueva style with signature features of traditional criollo music (including rubato, descending melodies, and a dramatic style of singing that verged on speech). Like the rioplatense milongas, Gardel’s tangos favored emotional extremes. The text of “Por una cabeza” unfolds in fatalistic terms, as the singer compares his thrilling but destructive love affair to a poorly timed horse race, in which he loses everything just barely “By a Head.”

New forms of dance music also developed during the Guardia nueva period. Standard tango orchestras now used two violins, two bandoneones, piano, and bass. The bandleader Julio de Caro (1899–1980) applied an expressive rubato style known as arrastre (to drag) that delayed the arrival of the first beat. De Caro’s orchestras featured virtuosic solos, bridges, and fills, along with percussive instrumental effects. Later bandleaders, such as Osvaldo Pugliese (1905–1995), Aníbal Troilo (1914–1975), and Horacio Salgán (1916-2016) elaborated upon this “Decareano” style of playing by intensifying the sense of arrastre and by enhancing the music with their own rhythmic and technical innovations. By 1955, the genre entered into a third phase, Nuevo tango (New Tango), which emphasized experimental extremes. The leader of this movement, Ástor Piazzolla (1921–1992), mastered the styles of both tango and classical music. He took composition lessons from

Alberto Ginastera the most influential Argentine classical musician of his day, and he studied in Paris with Nadia Boulanger, a remarkable teacher of students such as Aaron Copland. Coming from this background, Piazzolla produced a large number of classical works, including the chamber opera, María de Buenos Aires and the twelve-minute virtuoso showpiece, Le Grand Tango, which he dedicated to concert cellist Mstislav Rostropovich. Yet, ultimately Piazzolla found his original voice by integrating Argentine popular idioms with the intellectual structures of classical music. Through this synthesis, his music exemplified a level of technical sophistication that no tango musician before him had achieved.

With his Octeto Buenos Aires (1955–1957) and Quinteto Nuevo Tango (1960–1971), Piazzolla rejected established tango traditions. His experimental approach provoked controversy, and his confrontational attitude only made matters worse. He once remarked that Matos Rodríguez’s famous “La cumparsita” was “the worst of all tangos, the most dreadfully poor piece in the world” (although he still made multiple recordings of the piece). Piazzolla’s performances of the standard tango repertoire alienated traditional fans. His introduction of the electric guitar scandalized the musical establishment because previous ensembles had only used acoustic instruments. His complex rhythms caused audiences to complain that they could no longer dance to his music, which was his deliberate intent. Harmonically, Piazzolla’s use of harsh sounds, known as dissonances, pushed fans beyond their comfort zone, since they listened to the tango for enjoyment, not for a challenge to their ears. He further antagonized traditional listeners by eliminating the polished tango orchestra and emphasizing the strident sound of the bandoneón—an instrument that he played with an aggressive physicality that would soon become legendary.

La Camorra I (Fight No. 1) is a remarkable composition that illustrates Piazzolla’s experimental innovations, La camorra I (Listening Guide 7.5). This piece is scored for bandoneón, piano, violin, electric guitar, and bass—the composer’s classic quintet that became the standard for new tango musicians. In the powerful rhythmic sections of La Camorra I, Piazzolla’s syncopated patterns fall behind or get ahead of the main beats. These sections use prominent dissonances, even at the beginning of the piece, which is normally one of the most stable sections. Example 7.5 illustrates the opening piano part of La camorra I. The notes that are circled (E and G) represent dissonances that do not belong to the main chords of the piece.

Another daring feature is Piazzolla’s use of polyphony (multiple independent musical lines). Previously, tangos used homophony (i.e., they were based on a simple melody and accompaniment, as in the tango canción). Yet, because Piazzolla studied classical music, he could write complex polyphonic textures. One of the most intricate types of polyphony he used was the fugue (literally “flight”). Fugues involve two or more independent lines based on the same theme that artfully imitate each other. La camorra I includes the opening of a three -part fugue in which the bandoneón (3:09), violin (3:26), and electric guitar (3:42) successively present versions of a shared musical idea. One final touch is Piazzolla’s visceral grunt at 4:22. Before that time, no one had ever uttered such a guttural sound in a tango before, and his listeners were shocked beyond belief. Indeed, it is this gesture, along with many others, that demonstrate how far Piazzolla would push the limits of a genre that he deeply respected, yet forever changed.

Since the turn of the millennium, tourism has emerged as one of the most profitable Argentine industries. It has affected the cultural production of the tango, because one of the main tourist attractions in Buenos Aires is attending commercialized tango shows in local nightclubs. Promoted by large hotels, these shows represent a virtuosic but superficial image of the dance, which often appears combined with elements of Broadway musicals and Argentine folk genres. Nevertheless, the tourist boom has opened up new employment opportunities for performing musicians, some of whom may disagree about the way that tango is artistically represented, but who still reap sizable profits from the tourist industry.

Tourism aside, the contemporary tango movement has entered into a new creative phase as younger musicians engage with innovative projects that renew classic tango styles, repertoires, and practices. Modern tango artists have sought to recuperate historical knowledge of the genre, which reached a low point during the seventies and eighties and, at one point, verged on extinction. Their reconstructions of the tango have allowed them to celebrate a specific local identity and resist subjugation to foreign-dominated popular musics. Some groups, such as the Orquesta Típica Fernández Fierro, have revived the golden-age orchestras in the style of Osvaldo Pugliese. Other ensembles, such as 34 Puñaladas (34 Stabs) have updated the image of the Gardelian tango canción, incorporating old and new lunfardo lyrics and portraying themes of poverty, bitterness, and injustice that resonate with Argentine socioeconomic problems. Still other musicians, like Daniel Melingo, perform original compositions that combine tango elements with electronic instruments and sampling techniques, along with international rock styles and Latin American popular idioms. The creative possibilities for tango innovation seem limitless.

A leading contemporary tango musician is the pianist-composer Sonia Possetti (b. 1973), who studied with the golden-age bandleader Horacio Salgán. In 1998, Possetti formed a duo with her husband, the violinis Damián Bolotín. Four years later, she established a quintet that included Bolotín (and that has since later expanded into a sextet with the unusual addition of a trombone). Possetti is fully aware of the political implications of creating and performing tango in a country controlled by globalized economic and cultural interests. On the stage of a 2004 Boston concert, the contemporary tango scholar Michael O’Brien heard her say: “Our music is what we do so that they cannot invade us,” referring to the global music industry. Nevertheless, Possetti is receptive to the possibility of assimilating outside influences. In addition to standard percussion, she incorporates instruments such as the djembe (a large African hand drum), cymbals, bongo, and wood block. Her “Bullanguera” is based on a milonga rhythm (Example 7.4a) first sounded in the djembe. Later, she layers a salsa clave pattern in the percussion over the milonga foundation (2:17). Jazz techniques, such as the addition of “blue notes,” improvised solos, and sixteen-bar progressions, add new dimensions to the piece (Listening Guide 7.6). Taken as a whole, Possetti’s creative conception remains true to the roots of the tango, yet engages with a sophisticated range of current popular musics.

The last twenty five years have seen Argentine tango steadily regain broad cultural significance among young musicians who adopt the genre as a way of life. In parallel to the touristic circuit, the independent tango scene keeps expanding in number of groups, composers, and venues. The number of academic spaces and ensembles has grown as well, from the National University of the Arts’ Tango Orchestra, founded in 2010 by award-winning composer Ariel Pirotti, to elementary school bandoneón classes in the northeastern region of the country.

Julián Peralta is easily highlighted as a main composer and pedagogue. After leaving the Orquesta Típica Fernandez Fierro, the pianist focused on creating original material with Astillero and Orquesta Típica Julián Peralta.

In Quilombo (2017) Astillero pays homage to murga music through the use of its characteristic chain of syncopated rhythmic cells.

Other composers to listen to are Ariel Pirotti, with pieces like Despertar en la ciudad y Tifón navigating contemporary structures, new tango, folklore-inspired polyrhythms, and jazz.

Rock music began in Argentina during the 1950s and 1960s, as international popular styles spread through the mass media. Gradually, local songwriters created new forms of original music that incorporated Argentine characteristics. Beginning in the 1960s rock music engaged with national politics, as young people increasingly drew upon popular expressiv e forms to create a culture of resistance. The roots of this movement (1946–1955) date back to the charismatic leadership of Juan D. Perón and his wife “Evita,” whose dynamic yet controversial political styles contributed to the crisis. The Peróns’ policies of social justice for the poor provoked harsh criticisms among the upper and middle classes, who suffered in the resulting redistribution of power. The army, which alternately supported and conspired against Perón, staged a 1955 coup, shortly following Evita’s death. From 1955 to 1973, the Argentine people endured instability in the extreme, with a fragmented electorate of more than 20 political parties and frequent military takeovers. Many believed that the only hope of stability would come with the reinstatement of Perón to power. The former leader returned from exile to assume the Argentine presidency in 1973. Yet, he died that same year, bequeathing a precarious political legacy to his inexperienced third wife, Isabel Perón, who lost control of the government in 1976 when the military removed her in a bloodless coup. What followed was one of the most infamous periods in Latin American history.

For the next eight years, during the Guerra sucia (Dirty War), the government arrested, tortured, and executed its opponents, causing thousands of innocent people to “disappear” (see In Depth 7.3). According to Pablo Vila, an Argentine sociologist specializing in music of the period, the regime leveled most of its violence against Argentine youth between the ages of 18 to 30, who represented more than two-thirds of the missing population. Some young people belonged to activist groups that the government wished to suppress. Yet, others were university students and members of the intelligentsia, whose only “crime” consisted of thinking critically, which the regime perceived as a threat. Terrified by daily disappearances of friends and classmates, young people gathered together to listen to music and allay their fears. They attended concerts in Luna Park, the largest stadium in Buenos Aires. They subscribed to underground magazines that voiced the words that they could not speak. To Argentine youth, rock nacional meant more than listening to a favorite si nger or following a popular band—it had become a way of life.

The iconic Argentine group, Serú Girán, headed by the multitalented popular musician Charly García (b. 1951), defined the rock nacional movement during the Dirty War. The four members of the group came from eclectic musical backgrounds. García, who played keyboards and studied classical music, favored acoustic instruments. Guitarist David Lebón came from an electric rock and blues background. Pedro Aznar, the bass player, fused folk, rock, jazz, and tango styles together. Oscar Moro, the drummer, drew upon influences of the 1960s. As a group, Serú Girán defied classification. Yet, the musicians’ eclecticism appealed to a broad fan base that might otherwise have disagreed about the ideal way to convey their youthful voice of resistance. The 1979 LP titled La grasa de las capitales (The Grease of the Capitals) exemplifies Serú Girán’s approach to the musical poetics of political engagement. The song “Los sobrevivientes” (The Survivors) expresses the alienation of Argentine youth, who will “never have roots” since they have no safe place to live. The last two lines of the poem refer to Christ’s death in a metaphor that brings to mind the victims of the dictatorship. In the comforting instrumental music that follows, Serú Girán offers rock nacional listeners a sense of solace. By banding together in the memory of those who suffered a Christlike martyrdom, they can continue as the “survivors.”

In depth

In Uruguay, the development of popular music closely paralleled that of Argentina. The tango arose on both sides of the Río de la Plata, where it experienced an equally vital existence. In 2009, UNESCO acknowledged the binational contribution to the genre by declaring the tango an Intangible Cultural Heritage of both countries. Like Argentina, Uruguay suffered a neofascist military coup (1973–1985), preceded by an economic crisis and destabilization of the political system. The military seized control of the government and imposed an authoritarian regime that arrested, tortured, and killed thousands of people. Rigid artistic censorship and repression forced popular musicians into exile and their works underground. Uruguayans endured this terror by preserving their collective cultural memories and reviving an acoustic song tradition known as canto popular (popular song). The Montevidean singer-songwriter and leader of the movement, Daniel Viglietti ( 1939-2017 ) faced imprisonment and exile before returning to his homeland toward the end of the dictatorship. After the restoration of democracy, Uruguayan musicians cultivated eclectic styles. During the late 1980s, rock de arrabal (similar to rock chabón), appealed to unemployed youth with its aggressive combination of punk and heavy metal. In the 1990s, young Uruguayans who had spent much of their childhood abroad came home to form groups that reflected their bicultural experiences. One band, Peyote Asesino (named after the Mexican comic strip character), juxtaposed elements of hip-hop and hard rock; another, La Vela Puerca (The Pig-Like Marijuana Joint), mixed ska, funk, rap, and punk. Both groups signed deals with major record labels, through which they engaged with transnational music markets.

In Paraguay, considerable continuity exists between traditional and popular musics. Much of the popular music repertoire is based on contemporary updates of national dances such as the polca paraguaya. For almost 35 years (1954–1989), the Paraguayan people suffered under a repressive military regime. General Alfredo Stroessner maintained rigid control over the country and suppressed all political opposition. He treated indigenous groups inhumanely and was charged with frequent human rights violations. During the 1970s, rock music arose as a voice of social and political resistance. Yet, the local music scene developed slowly because Paraguayan bands lacked the resources to record their music and communicate with fans. The turning point came in 1983, when the Pro Rock Ensamble issued its first LP of rock nacional paraguayo, marking the official birth of the movement. Since the fall of Stroessner’s regime, rock music has flourished free of censorship and has achieved a wider distribution through the popular media. Today, eclectic mixtures of hybrid styles attract Paraguayan youth and play a vital role in social settings. Rock bands like Vecindad Autopsia fuse ska rhythms with Paraguayan folk, while singing in Guaraní.

As this chapter has shown, strong similarities connect the popular expressive forms of the rioplatense region. These connections date back to the tango, which initially pursued a parallel course on both sides of the Río de la Plata. Another shared reality stems from the devastating military dictatorships that took hold throughout the region. In Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay, popular music served as a powerful weapon in the struggle against political injustice and oppression. After the return to democracy, popular musics of these three nations experienced greater freedom because of the relaxation of censorship regulations. Rock bands openly distributed their works to the public through the mass media. Once rioplatense musicians entered into the global music marketplace, they came under its influences. Since the 1990s, popular groups have absorbed and combined international styles in a wide array of hybr id musical genres. At the same time, the con-stant presence of imported music has stimulated local musicians to redefine their identity as they seek recognition within the powerful economic space of transnational music markets.

Argentina in the Nineteenth Century

The rioplatense region has richly contributed to the tradition of Latin American classical music. Initially, this activity centered around the city of Buenos Aires, whose citizens embraced fashionable genres such as zarzuelas (operettas), operas, piano pieces, guitar music, and songs. Beginning around 1880, a generation of professionally trained musicians delved deeply into their roots, as the musicians sought to convey their identity. These composers cultivated the figure of the gaucho, whom they upheld as a symbol of the nation. Countries throughout the world all acknowledge their own types of horsemen, whether the charro from Mexico or the cowboy from the United States. During a period when Argentine composers sought recognition for their music abroad, the gaucho established their identity within an international community of nations.Two early composers who based their music on the gaucho were Alberto Williams (1862–1952) and Julián Aguirre (1868–1924). Both figures studied in Europe, where they came under the spell of musical nationalism, a movement that encouraged composers to draw upon their own cultural resources as a source of creative inspiration. Williams’s compositions closely resembled European Romantic models, but incorporated themes based on traditional Argentine genres. His talented colleague, Julián Aguirre, came from Basque roots and received his musical training in Spain. Aguirre’s works combined a delicate approach that resembled the piano music of Chopin, with an intuitive empathy for criollo rhythms and harmonies. His songs and piano pieces, such as the Huella and Gato (named after traditional Argentine genres), set the standard for many years.

Some pieces by Lopez Buchardo and Julián Aguirre can be found online at: Lopez Buchardo-Sonatina and Julián Aguirre-Canción en modo indio

Opera in Buenos Aires

Argentina has long prided itself on its splendid operatic productions—an achievement that dates back to the population of Italian immigrants who settled in the rioplatense region. Because opera originally had its home in Italy and has flourished there ever since, the Italo-Argentine population promoted this tradition as a symbol of its identity. Opera also attracted enthusiastic support from the criollo elite, which amassed enviable fortunes in the agricultural and livestock industries and had ample time to devote to leisure activities. Theaters and opera houses sprang up all over Buenos Aires; each one had its own singers, repertoire, and concert season.

The leading opera house of Buenos Aires is the Teatro Colón. When the building first opened in 1857, it was a state-of-the-art theater. The original building closed in 1888, in order to build an even more lavish theater, which opened 20 years later in a new location. Typical of turn-of-the-century theaters, the new Colón blended a variety of influences, including “general characteristics of the Italian Renaissance, solid German construction, and French ornamental grace and variety,” according to Víctor Meano, one of its chief architects. The Colón achieved international acclaim for its opulent physical surroundings, stellar productions, and faultless acoustics. Its performers have included the singer Enrico Caruso and the conductor Arturo Toscanini, along with Luciano Pavarotti, Plácido Domingo, and José Carreras (“The Three Tenors”). Clearly, the Colón was and is one of the great opera houses of the world.

The Teatro Colón emphasizes international opera, especially the standard Italian repertoire. However, since the new theater opened in 1908, it has produced a number of important national operas. Of these, Boero’s El matrero (The Gaucho Bandit, 1929) is regarded as the consummate work of the Argentine lyric stage. Its story centers on the death of an idealistic payador, whose failure to integrate into Argentine society resonated with contemporary audiences, who experienced some of the same social changes.

In 1929, a group of young composers banded together to found the Grupo Renovación (Renovation Group), through which they aimed to modernize Argentine music. Three key members of the group included: Juan José Castro (1895–1968), Juan Carlos Paz 1897–1972), and Luis Gianneo (1897–1968). Together, they studied the latest international trends and applied them to Argentine music. They championed dissonant atonal music (which lacked a tonality or key) along with serialism (which organized music around a prearranged series of 12 chromatic tones encompassing the black and white notes of the piano). They employed neoclassicism, reviving traditional forms of the past, but viewed from a contemporary perspective. These developments laid the foundation for the music of Alberto Ginastera—the leading composer of the next generation and one of the most original creative voices of South America.

Alberto Ginastera: South American Musical Spokesman

Alberto Ginastera (1916–1983) was born in Buenos Aires into a family of Italian and Catalan descent. After graduating from the National Conservatory, he established his reputation as a brilliant young composer with works like Estancia (The Ranch, 1941). Following a trip to the United States on a Guggenheim Fellowship (1945–1947), where he came into contact with the North American composer, Aaron Copland, Ginastera returned to Argentina. There he founded and directed three visionary music schools and produced some of his major compositions. Of these, his First Piano Sonata (1952) stands as one of the most popular works of the con- temporary piano literature. Ginastera is also known for his string quartets, orchestral music, operas, and cello repertoire. His second opera, Bomarzo (1966–1967), revolves around themes of torture, abuse, obsession, homosexuality, and sexual impotence. The Argentine reaction to this work provoked a scandal when the right-wing Onganía government banned it from the Teatro Colón despite its triumphant premiere in Washington, D.C., months earlier. By 1971, a combination of personal and professional circumstances caused Ginastera to make his home in Geneva, Switzerland. Ten years later, he received a prestigious award from UNESCO in honor of his lifetime of creative achievement.

Ginastera’s music reveals an imaginative synthesis of Argentine and international techniques. Early in his career, the composer conveyed his national identity through his memorable representations of the gaucho. He described how his trips to the pampas evoked feelings in him that were “now joyful, now melancholy, some full of euphoria, and others replete with a profound tranquility, produced by its limitless immensity and by the transformation that the countryside undergoes in the course of the day.” Out of these sentiments emerged his ballet Estancia.

To convey his identification with the pampas, Ginastera employed a wide range of expressive resources. He included sung and spoken lyrics from the national epic poem Martín Fierro. In addition, he represented the gaucho malambo in a contemporary classical context. Although a more traditional composer might have imitated the folk genre exactly, what mattered most to Ginastera was the rough and unpolished quality of the dance. He used dissonant contemporary chords to bring out the raw athleticism of the music. His tempos moved in dizzying speeds that verged on spinning out of control. His orchestration emphasized brass and percussion instruments, which had no relation to original gaucho music. Nonetheless, the strong associations of these instruments with military bands evoked the masculine quality the composer ascribed to the dance. “La doma,” one of several malambos from Estancia, exemplifies Ginastera’s imaginative representation of the gaucho.

After Estancia, Ginastera changed artistic directions. He avoided overt references to Argentine folklore, preferring to evoke a national character in an atmosphere “populated by symbols.” In his works of the late 1940s and 1950s, the composer demonstrated his mastery of classical forms and techniques. The opening movement of his First Piano Sonata (1952) uses a traditional sonata form with two contrasting themes. The sonata begins with a percussive theme in the low-middle range of the piano that recalls Argentine criollo music with its doublings in thirds. Yet, because Ginastera employs different doubled thirds in the melody and the harmony, his music is polytonal (a contemporary style of music using more than one key at once). The second theme sounds in the high register and contrasts with the opening idea (Example 7.7). This melody uses four notes of the Andean pentatonic scale, B–D–E–F#, set to modern harmonies. Throughout the passage, Ginastera alternates 6/8 and 5/8 time signatures, which gives the piece its modern rhythmic edge.

Structurally, the movement follows a three-part sonata form. Formally, it uses balanced classical proportions. After the exposition, which presents the two main themes in an opening statement, Ginastera embarks on the development, which manipulates the two ideas. Toward the end of the piece, the opening material returns in the recapitulation. Taken as a whole, the jagged rhythms and modern harmonies of Ginastera’s First Piano Sonata create a spontaneous sense of freedom. Yet, the structure of the work is meticulously planned, achieving that perfect balance between form and content to which the composer aspired.

Beginning in the 1960s, Ginastera forged experimental paths with his educational innovations. In 1962, he founded and directed the Latin American Center for Advanced Musical Studies at the Instituto Torcuato di Tella, which was a state-of-the art institution that trained new generations of Latin American musicians. Under Ginastera’s leadership, the center arose as the model for new music in Latin America. It awarded two-year scholarships to promising young composers, who studied with specialists in avant-garde music. The center boasted an electronic music studio—a costly (and therefore rare) institution during the 1960s in Latin America. Although in 1971 the center closed its doors, it offered a remarkably high level of contemporary music instruction during its brief but influential existence. Since that time, avant-garde music has flourished in Argentina. A leading composer was Gerardo Gandini ( 1936-2013 ) a brilliant piano virtuoso who studied with Ginastera and performed new tango with Piazzolla. Another major figure was Francisco Kröpfl ( 1931-2021 ) who founded the first permanent Latin American electronic music studio at the University of Buenos Aires. Marta Lambertini ( 1937-2019 ) was a prolific composer with an inclination toward stage music. One of her renowned works is the chamber opera, Hildegard (2002), which pays tribute to women composers whose voices were historically suppressed. Alicia Terzián (b. 1934) spends much of her time in Europe. She is one of the earliest Argentine musicians to use microtones (i.e., intervals smaller than the distance between the notes of the chromatic scale). Terzián directs an internationally recognized performance group that is dedicated to contemporary Latin American music. Not all composers have pursued experimental paths. Some have written in a more conventional style that is accessible to concert audiences.

To learn more about Guastavino, listen to two of his most popular songs, “Se equivocó la paloma” (The Dove Was Deceived) and “La rosa y el sauce” (The Rose and the Willow).

Carlos Guastavino (1912–2000) is known for composing over two hundred songs. Some of his vocal collections, such as Pájaros (Birds) and Flores argentinas (Argentine Flowers), evoke the Argentine landscape, while others, such as Doce canciones populares (Twelve Popular Songs) draw upon criollo influences. Guastavino studied classical music, but also came under the spell of folk artists such as Yupanqui. His music blends classical and vernacular idioms, causing doctrinaire members of the Argentine musical establishment to reject his works completely. Nevertheless, audiences have consistently warmed to Guastavino’s lyric melodies and expressive poetic settings. Over time, the number of his followers can only increase.

Uruguay developed an important postcolonial tradition of classical music. As in Argentina, a sweeping Italian immigration movement resulted in an enthusiasm for opera. The 1856 inauguration of the Teatro Solís, which opened one year before the Teatro Colón, marked a key event in Uruguayan music history. Like the Colón, the Solís boasted brilliant performances and fostered the creation of native opera. Nationalism played a leading role in twentieth-century Uruguayan music. Like Argentina, Uruguay aimed to establish a distinctive identity in response to immigration. Yet, because Uruguay came under the spell of Spain, Portugal, Brazil, and Argentina at different points in its history, composers had a wider spectrum of sources to dr aw upon as inspiration for their works. These materials primarily centered on the gaucho and the pampas, as in Eduardo Fabini’s Campo (Countryside, 1922), but could also include elements of Brazilian music and Afro-Uruguayan candombe. Some composers cultivated avant-garde approaches; one such composer was Carmen Barradas (1888–1963), who was known for her early experiments with alternative ways of notating music. Héctor Tosar (1923–2002) was a talented composer who cultivated classical forms and received acclaim for his music abroad. León Biriotti ( 1929-2020 ), Antonio Mastrogiovanni ( 1936-2010 ), Coriún Aharonián (1940-2017) José Serebrier ( b. 1938 ), and Sergio Cervetti ( b. 1940 ) represent more recent Uruguayan musical currents.

Miguel del Aguila (b. 1957) is a sought-after composer thanks to his expertly crafted language. Del Aguila achieves the rare feat of writing powerful pieces that while contemporary and complex, do not alienate audiences. His compositions build up anticipation and provide dramatic delivery without sounding derivative. The composer spent the first twenty years of his life in his native Montevideo, Uruguay, where he absorbed Latin-American folklore. After a decade in Vienna and many years in the United States, del Aguila incorporated jazz and other influences. The growing nostalgia led the composer to lean on his Latin origins, without any attempts at being authentic nor formal. The syncopated or irregular rhythms are personal expressions serving the dramatic goal, just like the harmonies depend on the melodies.

An example of del Aguila’s language is Obsessed Milonga, the last movement of Salón Buenos Aires, recorded by Dirk Meyer with the Augusta Symphony in 2022.

In Paraguay, the best-known classical musician was Agustín Pío Barrios (1885–1944), also known under the stage name, Agustín Barrios Mangoré. Barrios was a guitar prodigy who concertized abroad and resided for years outside his native country. He composed hundreds of guitar showpieces that reflect the diverse Latin American countries where he lived. In addition to Paraguayan sources, Barrios’s music is modeled on the Brazilian choro, Argentine zamba, rioplatense tango, as well as on European dances. Another major influence was the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, whose compositions were well known to Latin American guitarists through popular transcriptions and arrangements. La catedral (Listening Guide 7.10) is one of Barrios’s most celebrated compositions and a staple of the guitar literature. The composer is said to have received his inspiration for the work after hearing a performance of Bach’s organ music at the San José Cathedral in Montevideo. La catedral consists of three movements. The first is a prelude, an introductory piece in an improvisatory style. The second uses block chords that suggest the sound of a chorale (hymn melody). The third is a virtuosic tour-de-force that recalls Bach’s keyboard toccatas. It uses a rondo form, based on a memorable theme (A) that alternates with contrasting musical sections (B, C).

More recently, Diego Sanchez Haase (b.1970) is a a leading contemporary composer, pianist, and conductor born in Villarica, Paraguay. The recipient of several international awards, Haase has written pieces inspired by native mythology, and an opera in Guaraní. ÑOMONGETA: Opera Guaraní was premiered in Europe in 2019, and in New York in 2022 with Opera Hispánica , with Metro. Jorge Parodi conducting.

We have reached the end of our journey through the rioplatense region. Our time there has been all too short, especially when we consider the large geographical scope of the area and all it has to offer. This brief survey has emphasized certain core themes: the centrality of the guitar, the influence of immigration, the importance of the pampas, the significance of the tango, the interrelationship between politics and popular musics, the globalization of local repertoires, and the connections between nation-building and contemporary classical music. Yet, if rioplatense music shares so many common features, why are the pieces all so different? And how can such diverse meanings be ascribed to them? The answer resides in the cultural plurality of the region, which remains one of its defining features. As you continue to explore the musics of Latin America, it is important to remember that the concept of diversity applies not only to the specificity of individual regions, but also to the wealth of musics within them.