Performers assemble on stage for a concert by the Nortec Collective from Tijuana, Mexico. Two DJs, Bostich and Fussible, stand in the center with their backs to the audience and facing a large console, glowing rectangular control panels in their hands. Flanking them are performers facing forward who play music from distinct traditions of the northern border region; their instruments include the button accordion, bajo sexto, tuba, and trumpet. Suddenly the hall comes to life with the throbbing pulse of dance beats. Some consist of sampled Afro-Latin percussion, some are electronically generated, some are reminiscent of U.S. soul from the 1970s, some recreate the sound of a Mexican polka. The backtracks change every few minutes, with one groove eliding almost seamlessly into the next. Live musicians improvise short melodies against the rhythms, making their traditional instruments sound rather avant-garde. At the same time, a video jockey projects images onto a large central screen and manipulates smaller projectors tilted toward the ceiling and side walls. Images depicted include scenes of working-class Mexican life, well-known buildings in Tijuana, Mexican cowboys, old U.S. automobiles, as well as kaleidoscopic distortions of faces, instruments, animation, and written slogans, all in scintillating color. The wild mix of traditional and sampled sounds assembled by the Nortec Collective allows the group to explore the border experience, linkages between U.S. and Latin American culture, between the rural and cosmopolitan, and between the developed and developing worlds.

2500 miles to the south in the state Huehuetenango, Guatemala, the rock group Sobrevivencia (Survival) uses music to help preserve traditional Indigenous cultures in danger of extinction as they reconcile traditional songs and instruments with international trends. The group’s CDs from 2001 and 2002 feature compositions in the native Mam language as well as Spanish, and accompany Indigenous flutes and percussion with the electric guitar. Members use Indigenous rock to draw attention to pressing concerns of Mayan descendants — land disputes, poverty, environmental damage, lack of access to education — and to pressure the national government for support.

Another 4000 miles to the southeast in Rio de Janeiro, Brazilian rapper MV Bill (Alex Pereira Barbosa, “Mensageiro da Verdade” or “Messenger of Truth”) uses hip hop sung in Portuguese in a similar way, describing conditions within the infamous slum where he was raised, the Cidade de Deus (City of God) 1 This neighborhood has been immortalized in a powerful film, also called City of God. [add hyperlink to film, or film trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dcUOO4Itgmw] . He not only advocates forcefully for social justice through music, but has organized a network of NGOs (non-governmental organizations) that provide academic support and artistic training to underprivileged youth. His music frequently references drug trafficking and related violence in Rio, as well as police corruption, the need to valorize African heritage, and the importance of education as a means of getting ahead in life. His first single, “Soldado do Morro” (Soldier of the Slum) was banned by the police after they misconstrued it as glorifying violence.

In Bogotá, Colombia, audiences gather in a prominent concert venue to listen to a performance of the experimental classical piece Creación de la tierra (Creation of the Earth) by composer Jacqueline Nova Sondag (1935–1975). Nova won accolades at the First Festival of Latin American Music in Caracas and went on to study at the famed Instituto Torcuato Di Tella in Buenos Aires. She uses as the basis of this composition a recording of an Indigenous shaman who recites several chants, including some describing mythic tales about the earth’s creation. Nova alters the shaman’s voice electronically, separating it into multiple short segments, looping them and playing them backwards and forwards at various speeds against one another, creating a chorus of unintelligible voices and rhythms, all derived from the same recording. Only at the end of the work is the voice heard in its original form. She uses the piece as a way of commenting obliquely on the Latin American experience, the confluence of the modern and the traditional in daily life, and of the contested nature of Latin American identity.

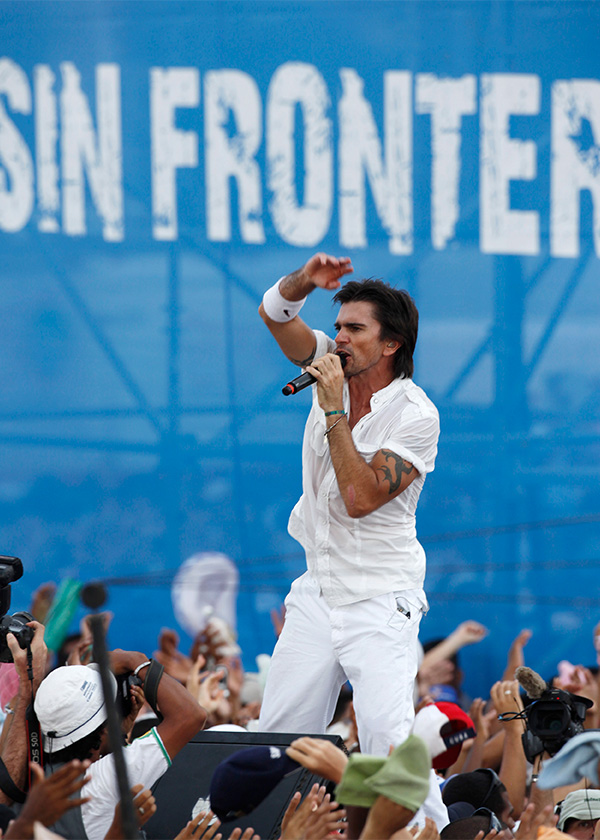

On a stage in Havana’s Plaza of the Revolution, a very different sort of Colombian artist faces a crowd of over a million enthusiastic fans at a “Concert for Peace.” Juanes (Juan Esteban Aristizábal Vásquez) organized the event in September 2009 in an attempt to improve US-Cuban relations through the use of music, suggesting it was time to “put aside ideological differences.” Other performers and groups in attendance include Cubans Silvio Rodríguez and Los Van Van; Puerto Ricans Danny Rivera and Olga Tañón, Juan Fernando Velasco from Ecuador, CuCu Diamantes, and the U.S.-based Yerbabuena. Cuban crews transmit free footage of the five-hour event to international television stations Univision and Telemundo, who in turn broadcast the concert throughout the hemisphere. Both the U.S. and Cuban governments provide support, issuing special visas to allow for the travel of performers and technical production teams. Juanes, who lives in southern Florida, receives at least one death threat from Cuban-American activists opposed to his performance in the wake of the event. A small anti-Castro group known as Vigilia Mambisa (Revolutionary Vigil) brings an industrial steam roller and sledge hammers out onto the streets of Miami, publicly crushing his CDs in protest 2 The Miami Herald, Time magazine, and other sources covered protests of this event extensively. .

These brief descriptions of music making in present-day Latin America underscore its diversity, its vibrancy, and its linkages to an array of pressing concerns for the region and the hemisphere. Many such concerns appear in later chapters of this textbook, and are discussed below. Music is a vital component of Latin American culture and an important means of understanding it. While the study of Latin American society in a broad sense helps us understand and appreciate Latin American music, the music itself provides an opportunity to learn about the broader society as well. In terms of its sound structures and instrumentation, its performances, its associations with particular communities and activities, and its lyrics, music can focus our attention on important aspects of the region, in the past and present.

The history of Latin America and the United States are closely intertwined, and in fact part of the same story. The entire Western Hemisphere developed through a common process of European colonization, for instance, and has been in economic, political, and cultural contact for centuries. All parts of the Americas had native populations whose cultures tended to be misunderstood and ignored by European colonists, if not actively persecuted. All forcibly brought West Africans to work on plantations or cities as part of the Atlantic slave trade. And of course large parts of what is now the United States actually belonged to Spain or to Mexico up until the mid-nineteenth century.

Latin American immigrants and Latinos (U.S. residents of Latin American ancestry) now constitute the most rapidly growing part of the U.S. population. As of the year 2000, they became the country’s largest minority group as well, surpassing African-Americans; their ranks have grown to well over fourteen percent of the population. Projections indicate that by 2050 the Latino/Latin American community in the U.S. will grow to over one hundred million and constitute twenty-nine percent of the total population. Large sections of southern Florida and the southwest are primarily Spanish-speaking already, a harbinger of further changes to come.

How exactly can we define Latin America as a region and as a musical area? Generally, the term “Latin America” applies to those parts of the Americas in which languages derived from Latin, especially Spanish and Portuguese, are spoken by a majority of residents, as well as to Catholic countries that have traditionally observed Sunday mass in Latin. Collectively, these nations cover a vast territory spanning two continents, with a total population roughly double that of the United States. Many have questioned the appropriateness of the term “Latin America,” given that numerous ethnicities, languages, and immigrants can be found in the region (including First Peoples, the original inhabitants), and that their ties to “Latin” culture or Catholicism are often tenuous, but the phrase is widely used nevertheless. Latin America can be divided into several smaller areas based on geographic and cultural differences. These areas include North America (comprising Mexico and the U.S. Latino population), Central America, the Spanish-speaking Caribbean and circum-Caribbean, Portuguese-speaking Americas (primarily Brazil), the Southern Cone (Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay), and the Andean region. Countries such as Colombia and Venezuela have areas that correspond both to the Andes and the circum-Caribbean. Most consider French-speaking countries of the Americas (e.g., the francophone Caribbean) part of Latin America as well, and English- or Dutch-speaking Caribbean or circum-Caribbean areas. However, they are not discussed extensively in this volume in order to focus greater attention on Spanish-and Portuguese-speaking areas whose music and culture share many attributes with those discussed in other chapters.

Given the diversity of countries and populations comprising Latin America, it is difficult to determine the common denominators that unite them in a cultural or musical sense. Some commonalities exist, however, and each speaks to important factors that have shaped the experience of Latin American people. A few examples are provided below.

As mentioned, one experience shared by Latin American nations is a history as colonial possessions of Spain, Portugal, or other European powers. Colonialism refers to the process by which one nation invades a foreign country or region, claiming the territory as their own and placing the native population forcibly under their control. Aggression of this sort has a venerable history dating back to ancient times, but in the case of Latin America the conquest by Iberian powers took place largely between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries. The impetus for colonialist expansion there derived largely from profits to be made from exploiting the natural resources, and a desire to extend European influence globally. Technological advances in sea faring and in military weapons — especially the use of gunpowder — made possible the control of new territories by relatively small European armies.

Columbus claimed all new territories he encountered as colonial possessions during his first voyages of across the Atlantic. After he returned to Europe to tell of the new lands, Spanish and Portuguese rulers made a pact with Pope Alexander IV to divide the Americas between them. The Pope’s decree suggested that the goals of the colonizers included “civilizing” any Indigenous groups encountered and bringing them the Christian faith, but documents written by early missionaries suggest that this was actually a low priority. Friar Bartolomé de las Casas’ Short History of the Destruction of the Indies, for instance, asserts that Spanish explorers cared little for native peoples and often treated them with unparalleled cruelty. It appears that the first decades of conquest in the hemisphere led directly or indirectly to the death of millions of Indigenous people.

As one might expect, Latin American colonies in the Americas tended to adopt the values and cultural orientation of the European powers that established them. The ruling elite promoted music associated with the Catholic church and Europe’s aristocracy, while soldiers and settlers of more humble origins brought with them instruments and folkloric traditions from various parts of Spain and Portugal. Though they encountered new forms of music, most colonizers (especially elites) ascribed to notions of European superiority and tended to belittle the cultural forms of the non-European peoples whose territories they controlled. Such negative attitudes persisted for some time and began to change significantly only in the early twentieth century. This book represents part of an ongoing process of rectification, an attempt to introduce the reader to all kinds of Latin American music on equal terms.

Musical examples demonstrating the effects of colonialism are found throughout this volume, but perhaps most consistently in Chapter 2. Pieces such as “Hanacpachap cussicuinin” (Listening Ex. 2.1) document the way colonial authorities shaped Native practices of listening and ritual worship to conform to Catholic orthodoxy. The countless musicians of racially mixed backgrounds who have composed music in European-derived styles since the conquest testify to the strong influence of Iberian heritage in cultural terms, and to the social prestige and potential for lucrative employment with which it is associated. Examples of Indigenous- or Afro-descendant composers in the classical idiom range from Juventino Rosas, a musician of Otomí Indian descent active in nineteenth-century Mexico (see Chapter 3) to Tania León, a Afro-Cuban composer active today and discussed in Chapter 9.

Any overview of Latin America must inevitably address issues of race and cultural hybridity, which are fundamental to the region. Especially in literature from past decades, Latin America is often described as having a “tri-ethnic” heritage. The three facets of heritage in question are Indigenous, sub-Saharan African, and European; all three have contributed centrally to Latin American culture and society. Influences from these and other ethnicities have combined in many ways over time, resulting in complex cultural forms that have no single point of origin. Scholars of Latin America use a dizzying array of terms to describe this process of fusion: hybridity, mestizaje, creolization, transculturation, syncretism, and others. Mestizaje (or mestiçagem in Portuguese), perhaps the most common term, derives from the Latin word for mixture. It referred initially to racial mixture, and later to hybrid cultural practices as well. Beginning in the early twentieth century, authors such as José Vasconcelos in Mexico and Gilberto Freyre in Brazil began to advocate a conception of the Latin American character in which mestizajefigured as a central component. Over time, their views have been adopted widely, particularly in the construction of nationalist discourses. It is important to recognize that early writings on the subject often celebrated the notion of mestizaje in the abstract, without attention to the brutal and often dehumanizing realities of colonial domination that gave rise to it.

Scholars estimate that over a hundred million Indigenous people may have inhabited the Americas at the time of Columbus’ arrival, divided into thousands of distinct linguistic and social groups. The greatest concentrations lived in Central America and the Andes, but substantial numbers lived in virtually all areas. Their populations dwindled dramatically after the conquest as they fell victim to European diseases as well as starvation, armed conflict, overwork (as many were enslaved), and other factors. Despite this, some countries continue to boast large Indigenous populations today including Bolivia, Brazil, Guatemala, Mexico, and Peru. Indigenous groups perpetuate their own unique forms of musical expression that run the gamut from traditional to mestizo to cosmopolitan. No individual’s race determines their musical preferences definitively, of course, but only suggests stronger exposure to certain forms of traditional music, and possibly stronger identification with it.

Colonists brought approximately twelve million West Africans to Latin America as slaves, where they and their descendants suffered horribly, yet persevered and strongly affected musical traditions in many areas. Most worked initially on plantations that cultivated sugar and other goods for export. More Africans were taken to Brazil than any other single country, approximately 39% of the total, and the Caribbean as a region became home to another 40%. Chapters devoted to these areas will discuss distinct African-influenced Latin American musical traditions, and the ethnic groups with which they are associated, in greater detail. Colonists took the remaining 21% of the West African population to other parts of Central, North, and South America, with only about five percent ending up in the United States. Needless to say, the demographics of particular regions with a large Afro-Latin presence have resulted in styles of musical expression distinct from those in areas dominated by European settlers or Native groups. Play brief segments of Listening Exs. 5.2 (a Yoruba-influenced religious piece), 5.3 (a Kongo-derived piece), 6.4 (a recording of an African musical bow and percussion) and 4.4 (combining African-derived percussion with Indigenous reed flutes) to compare a few of the diverse sounds of overt Afro-Latin heritage. The authors of this book discuss these other African-influenced traditions, such as Ecuadorian currulao music, represented in the photo below by the well known group Berejú.

In the same way that Indigenous and African-derived traditions in the Americas represent hundreds of distinct ethnic groups with their own instruments, dances, and musical repertoire, European traditions in the Americas demonstrate many distinct influences. Traditional music from the Iberian peninsula itself contains strong influences from north Africa, owing to the many centuries that Arabs ruled the region. Guitar and lute playing, as one example, highly influential within Spain and elsewhere, developed from Arab culture and instruments. Spanish cities such as Madrid had populations of sub-Saharan African slaves as well who influenced musical life there long before the conquest of the Americas began. These and other facts underscore how problematic it can be to adopt broad categories such as “European music” without qualification. On a fundamental level, almost all music demonstrates cultural fusion to greater or lesser extents.

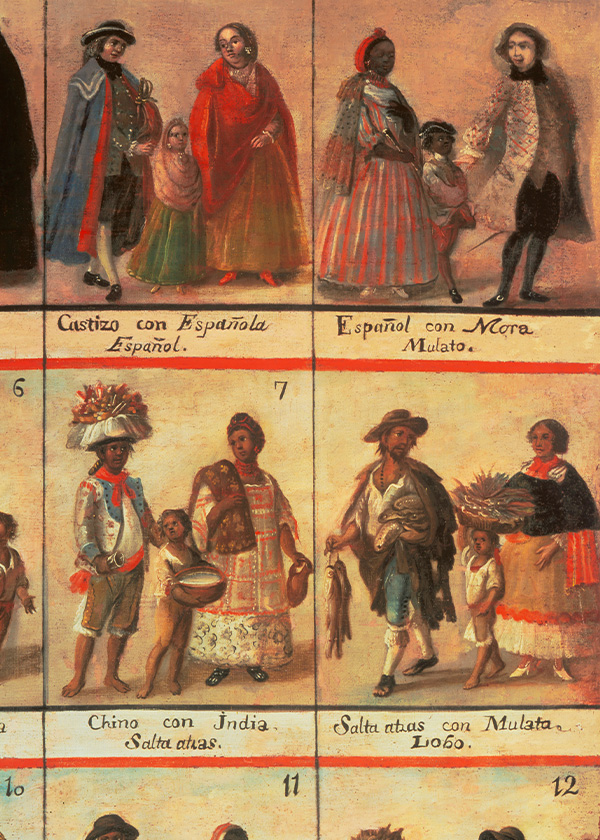

European colonization in Latin America, as opposed to the United States, began with relatively small numbers of immigrant families. Instead, soldiers, government administrators, businessmen, adventurers, and the like — the vast majority of them men — settled the colonies. They often developed relationships (consensual or not) with Black and Indigenous women, and thus issues of racial mixture in their children came to the fore quickly. It is no exaggeration to say that colonial Latin American societies obsessed over issues of race for centuries as a result. Prevailing ethnocentric views until the mid-twentieth century suggested that non-European people were not as “evolved” as Europeans and that mixture caused potential damage to further generations. Paintings and writings from the eighteenth century demonstrate this perspective, and the multitude of terms generated to distinguish various gradations of racial mixture: in Spanish such terms include mulato (half African, half European), mestizo (half Indigenous, half European), castiso (half mestizo, half European), morisco (half mulato, half European), lobo (half Indigenous, half African), sambaygo (half Indigenous, half lobo), coyote (half Indigenous, half mestizo), etc. Some of this vocabulary has survived into the present, and other terms have emerged more recently.

Similarly, a vast array of music has emerged in the Latin American context, some of it very European-sounding, some quite mestizo or hybridized, some derived directly from Indigenous or West African heritage of various sorts. This range of expression underscores the fact that although Latin America is characterized by racial and cultural mestizaje generally, it is far from homogenous. Distinct class-based and ethnic groups persist that negotiate among many musical influences. They may choose to perpetuate their own unique forms of music in relative isolation. They may forsake traditional genres in favor of modern mass-mediated music, attempt some synthesis of the traditional and modern, or cultivate multiple forms of music making in distinct contexts.

Mixed-race people themselves figure prominently in the historical development of hybridized musics; as a group many have been caught between distinct cultural worlds and have been forced to reconcile or juxtapose them. Latin American music represents a relatively democratic space in this sense, giving voice to expression from the margins of colonial and post-colonial society. Often the wealthy and powerful, who tend to be of European heritage, initially reject music popularized by working-class and mixed-race people, believing it crass or uninteresting. Yet the same music tends to gain popularity among ever wider segments of the population and eventually emerges as an important form of collective national expression (the same could be said of jazz, rock, and rap in the United States). Despite a certain ongoing ambivalence about Native and African-derived culture on the part of elites, populations as a whole have come to realize that mestizo musics serve as an important marker of the Latin American experience.

The degree of urbanization of Latin America since the mid-twentieth century is striking and represents a significant trend in every country. In the 1940s and 1950s, most residents still lived in fairly isolated, rural areas; they performed at least some forms of community-based traditional music and maintained a certain cultural distance from others. Since the year 2000, however, about 75% of the population lives in cities. Rural migrants have tended to settle in shanty towns on city peripheries, or in the tenement houses of poorer urban sectors, bringing once-rural music and dance traditions with them. In these new contexts, rural expression often changes, incorporating new sounds and influences from both the region and from around the world.

In this sense, the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have accelerated trends toward cultural fusion evident since the first years of colonization. The invention of mestizo string instruments such as the charango (Fig. 8.12) centuries agoin the Andes can be viewed as part of a similar process involving the reconciliation of European and Indigenous influences, as one example. But of course the degree and complexity of hybridity has increased of late. Argentine tango (Fig. 7.7) and Dominican bachata (Box 5.2) both developed in urban areas, for instance, and both fused countless international and local influences together. Other examples of intercultural exchange include reggae-influenced samba variants from northeast Brazil and experiments fusing salsa and flamenco music in Spain and in the Caribbean.

Many Latin American communities thus live with one foot in the practices of the rural past and one in transnational urban contexts. Music itself often embodies such discrepancies and tensions through the incorporation of new forms of instrumentation, rhythm, contexts for performance, the juxtaposition of disparate elements, and so on. A traditional Indigenous rattle or shamanic chant may be heard on a recording in tandem with synthesized sounds, much as in the case of Jacqueline Nova’s music, discussed earlier; traditional repertoire from a specific region can be sampled, combined with a backbeat, and re-interpreted as dance music throughout the hemisphere and beyond. Néstor García Canclini is one of many authors to study this phenomenon. He notes that performers such as Panamanian Rubén Blades and Argentine Astor Piazzolla regularly combine a diversity of elements in their compositions including influences from jazz, local traditional music, and international classical repertoire. As a result, it is increasingly difficult to make hard and fast distinctions between urban and rural traditions in the region, or to categorize them in other ways.

A trend related to urbanization is that of constant migration or movement in search of work, either within a particular country or outside of it. Migrants have contributed to and popularized many of the musical genres discussed in this volume. Examples include música sertaneja (Listening Example 6.3) and other rhythms from northeastern Brazil that are now popular in urban centers because of the internal displacement of rural populations. Various styles of Andean music, like chicha (Fig. 8.12; Box 8.4), emerged out of a similar synthesis of rural dancemusic brought by highland immigrants to Lima, along with rhythms from commercial Colombian genres and elements from foreign pop music. More broadly, the intense nostalgia for rural life and imagery found in much traditional music of Mexico, Argentina, and elsewhere derives in large part from the movement of rural populations to cities in recent years.

The international migration and movement of Latin Americans is also increasingly common, the experience of life on or across borders, and/or the frequent crossing of cultural boundaries of various kinds. Individuals from Mexico or Central America may travel to and from the United States in search of employment, bringing their music with them and acquiring a taste for mainstream U.S. artists; South Americans may do the same, or travel to and from European cities. All of this has led to a marked deterritorialization and diversification of heritage. Together with the expansion of the mass media, it has created a situation in which music circulates more widely and rapidly than ever before. Latin American musical forms can no longer be associated exclusively with Latin America, and the music performed by Latin Americans themselves often sounds quite cosmopolitan, heavily influenced by international pop or other repertoire.

Sound reproduction technology itself has influenced the development of Latin American music in significant ways, beginning at least in the 1920s. The international popularization of genres such as the Latin American bolero at that time (see Chapter 5) owes much to the emergence of commercial radio, for instance, and the sale of 78-rpm records. Many genres such as Mexican mariachi music gained prominence as a national musical form as the result of dissemination through motion pictures, and changed significantly in stylistic terms as part of that process. More recently, LP records, television broadcasts, cassettes, CDs, music videos, internet broadcasts, and mp3 downloads have all had an impact on musical dissemination and the development of new genres.

In the past, large business interests controlled technologies such as record and CD production and largely determined what sorts of music to record and distribute on them. However, the relatively low costs associated with internet streaming and inexpensive digital recording techniques appear to be putting control of music making and dissemination back in the hands of individual performers and communities to an extent. DVD piracy and the black-market economy have also shifted control of recorded music sales away from corporations and toward local communities in some cases.

Finally, tourism and self-conscious displays of heritage represent an increasingly important factor in the representation of Latin American music, and point to the broader theme of cultural movement discussed above. In our increasingly globalized and interconnected world, performers who once made music only for themselves and/or their immediate community now primarily entertain visitors from elsewhere. In self-conscious displays of musical tradition, individuals make decisions about what repertoire to include and exclude, which pieces best represent themselves to others, where to perform, what to wear, whether to charge admission, and so on. All of this fundamentally shapes the musical experience, needless to say, often altering performance radically relative to earlier times.

Displays of heritage may be supported by international organizations, federal governments, regional officials, local communities, or performers themselves, each with their own unique interests and motivations for doing so. Performers may simply hope to earn a living from tourists, or to achieve greater recognition for local music that has been marginalized or ignored. State or federal governments may also underwrite music making because of its potential to attract revenue, or as part of politically motivated projects that use music as symbols to unify the population. International organizations may promote local music making as part of development projects, or to support endangered heritage. The UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage initiative, for instance, has documented many kinds of Latin American music, archiving photos, video, and commentary about them on the web. It has supported Afro-Uruguayan candombe (see Chapter 7) and Afro-Dominican drumming of various sorts; Indigenous Aymara festivals from Bolivia, Chile, and Peru; Garifuna music in Belize, Guatemala, and Honduras; El Güegüense street celebrations in Nicaragua; Indigenous voladores rituals in Mexico (see Chapter 3), and many others.

Carnival parades represent perhaps the best known example of Latin American heritage that draws huge international crowds, whether to Rio de Janeiro, Oruro Bolivia, or Trinidad and Tobago. Other high-profile events include Inti Raymi, the Festival of the Sun (a reenactment of pre-conquest Incan rites that takes place in Machu Pichu, Peru), or the Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) celebrations on Lake Pátzcuaro in Michoacán, Mexico. Thousands of smaller regional events take place throughout Latin America as well. They include the annual Viña del Mar music festival in Chile, the Cosquín folklore festival in Argentina, boi-bumbá celebrations in various parts of Brazil (Fig. 6.4), and so on. Individual hotels frequently organize presentations of local music, and musicians themselves may cater to the perceived preferences of tourists. One example of the latter is the proliferation of trios and quartets in Havana, Cuba that formed in the wake of the Wim Wenders film Buena Vista Social Club, all of them playing the same half-dozen songs from the film again and again.

Many related trends could be mentioned that impact the development of Latin American music and that receive attention in this volume. The marked wealth disparities associated with most Latin American countries, as one example, have their corollary in frequent musical dialogues among various groups, representing the centers and peripheries of their populations. The turbulent political history of the region has been documented in and influenced by a history of socially engaged music of various sorts, bringing attention to injustices or inspiring collective action. The machismo associated with much Latin American culture is reflected in the male-dominated nature of music performance and the lyrics of many songs. The region’s emphasis on social dance and related music has contributed to its preeminence as an international exporter of dance rhythms, from the earliest centuries of colonization to the present. And the fractured or divided nature of many Latin American populations has led to ongoing debates over the sorts of music that most effectively represent national or regional character.

The authors of this textbook have multiple goals in mind. They hope to provide you with a feel for the diversity of Latin American music and the history of the development of major genres, as well as a description of their unique musical characteristics and of the local meanings and contexts associated with them. All chapters strive to provide you with an appropriate vocabulary for analyzing Latin American music and expand your ability to speak and write about it. All chapters identify broad tendencies that have influenced the development of music within the regions they analyze in detail. And all intend to serve as a point of departure for further study by providing additional reading and listening suggestions. The latter are especially important to guide you toward additional information on the many topics touched on only briefly because of space constraints. As a means of encouraging an international perspective on musical scholarship, and in order to recognize the contributions of scholars from Latin America to their own musical histories, the authors have included additional reading suggestions in Spanish, Portuguese, or other languages as appropriate in addition to English in conjunction with each chapter.

In some cases, a discussion of musical elements has necessitated the transcription of short segments of music within the text. Whenever possible, these examples are included in two formats: Western staff notation (for those familiar with it) and an alternate form of notation, such as numeric ciphers or something known as TUBS (short for Time Unit Box System; see appendix). It is hoped that the use of multiple notation formats will afford those unable to read Western music easier access to this information. The appendix also includes background information on common musical terminology, and suggestions as to how one might approach the analysis of Latin American music.

In order to make each chapter consistent, contributors have divided their essays into sections that include a discussion of traditional music, popular music, and classical music. These terms deserve some explanation; though they are useful as a means of classifying music in a general sense, the distinctions between them are often far from precise. They should be viewed not as entirely separate categories, but rather as a means of emphasizing predominant characteristics.

Traditional music (also called “folk music”) is typically associated with rural contexts, with specific places or regions, and with groups of people that have cultivated the music for generations. Performers often learn such repertoire by ear from friends and family, rather than through formal study, and may never write it down in notated form. Such music invariably changes over time, but often not as rapidly as in the case of popular or classical music. Community members may perform it for themselves as a form of entertainment, as part of religious worship, or in other contexts. They would not tend to stage the music for an audience, but rather integrate it into their own day-to-day activities. Naturally, exceptions can be found for almost all the characteristics listed above; many performers of traditional repertoire do perform in formal contexts for money, for example, and some traditional music is played far from its point of origin. The urbanization and globalization of music making described above has strained existing conceptions of “the traditional.”

Popular music (sometimes called “commercial music”) is usually associated with urban contexts and dissemination through the mass media. Its audience base tends to be diverse in terms of ethnicity, age, sex, and other factors; often, fans of a particular artist may live in different countries or on different continents. Popular music performers almost always expect payment for their shows and recordings. They frequently make a living from their music, and they may or may not have extensive formal training. They often play on electrified instruments, incorporating influences from U.S. or European genres. Popular music tends to change rapidly in a stylistic sense, following trends and fads of the consumer market.

Problems exist with this definition as well. Some popular musics do not have a terribly diverse audience, for instance, and cater instead to specific minority groups. In the twenty-first century, virtually all forms of music tend to be mass-mediated, commercial or not. Some popular musicians begin their careers as musicians of traditional repertoire, or as classical musicians, and thus defy easy classification. It is also important to recognize that the phrase “popular music” (música popular) within Latin America has connotations different from those in the United States. In Latin America, it might be translated as “music of the people” and can refer to traditional as well as commercial music; often the phrase has political or oppositional connotations. This textbook ascribes to the standard English usage of “popular music” unless otherwise indicated.

Ethnomusicologist Thomas Turino (2008) has developed a further critique of terms such as “traditional” and “popular,” noting that while they provide some insight into the origin of musical styles, their associations with particular people and places, or their relation to the media in broad strokes, they provide little insight into the nature of music making as a social activity. He suggests alternate categories focused on music making including participatory performance (events in which few divisions between performer and audience exist) and presentational performance (events in which one group of musicians/dancers provides music for a relatively passive group of spectators). Turino further distinguishes between various types of recorded or electronically generated music including “high fidelity” (recorded songs intended to represent the sound of live performance) and “studio audio art” (the manipulation of sampled or other sounds not intended to reference live performance). Of course, divisions between these “fields” or categories frequently become blurry as well and may overlap substantially. Nevertheless, it is useful to examine genres discussed in the following chapters from the perspective of Turino’s model, since many traditional and popular forms of music may be performed simultaneously in community settings and on stages, are manipulated and recorded in studio contexts, and circulate socially in multiple ways.

Classical music of European derivation (also known as “academic music” because of its association with conservatories, “art music,” or “concert music”) first developed as the music of the aristocracy, and of the Catholic church, before spreading to the American colonies. It is a virtuosic tradition, one that typically requires years of study in formal contexts to master. Usually, the music is notated and supported by a substantial body of written theory that describes the appropriate ways to compose and interpret it. Over the past century, classical repertoire in the European tradition has become increasingly experimental as composers search for ever new and more unconventional ways of organizing sound. It should be recognized that many different types of classical music exist, for instance genres derived from court traditions in China, India, Japan, and Indonesia. This book uses the term to refer to compositions written by Latin Americans, based at least in part on European models.

Classical music may be the least problematic of the three categories discussed here, but it too can be difficult to distinguish from the others. Musicians of many different backgrounds now boast some classical training, as one example, and incorporate classical influences into folkloric or popular repertoires. Traditional and popular musics can be highly virtuosic in their own right, making it difficult to differentiate between repertoires in that respect. Classical composers for their part often fuse elements of traditional and popular musics into their compositions as well, further blurring the categories. Classical music is no longer associated with an aristocracy, but is increasingly performed and listened to by audiences of diverse backgrounds, and circulates commercially as a product to be bought and sold.

Two related disciplines have contributed to the scholarship in this textbook, providing at least partially distinct focuses and modes of analysis. The first is musicology, which in its modern form dates from the late nineteenth century. Musicology, broadly defined, is the scholarly study of music as a physical, aesthetic, and cultural phenomenon. Though its objectives are ample, in practice many musicologists (especially of past decades) have specialized in the analysis of classical repertoire, on the historical development of instruments or genres, or on the careers of particular formally trained composers or performers. Alternately, some musicologists have studied performance practice, the appropriate interpretation of primarily classical repertoire from earlier historical periods. Much musicological work takes place in archives with musical scores and written documents from the past. Given Latin America’s long colonial history — approximately 500 years — and the substantial body of classical repertoire composed there, studies of this nature have much to offer.

The other discipline that has contributed to this textbook is ethnomusicology, a younger field dating in its modern form from the 1950s and one more influenced by cultural anthropology than history. The “ethno” in ethnomusicology comes from “ethnography,” the systematic study of human societies through direct observation and interaction. Emphasis within this discipline is on the relationship between musical and social activity, and on the meanings of music for particular groups. It should be noted that greater attention to the contexts for music making, an analytical shift from a focus on musical “products” (instruments, pre-composed musical works, recordings) to the processes of music making, and on the reception of music by the public have affected musicology as well, and other disciplines in the humanities. For the most part, ethnomusicologists have tended to study the music of developing countries or immigrant groups, though increasingly they also examine music from the United States or Europe. They may study the classical repertoire of various countries, but more often traditional or popular styles. Their analysis, based on extended stays within the communities they study, usually emphasizes present-day music making rather than genres from the past.

The approach adopted by the authors of this textbook combines insights and approaches from both musicology and ethnomusicology. They incorporate historical analysis, the analysis of musical sound, and an interpretation of the music’s meanings and uses in particular settings. They introduce the reader to as many kinds of music as possible and consider it from various perspectives, though special emphasis is placed on genres that are heard in Latin America today or that have strongly influenced present-day music making. The authors consider as diverse a musical repertoire as possible within the regions and time periods they discuss, giving equal weight to Indigenous, European-derived, and African-derived heritage, mestizo and commercial forms, as well as classical music. They have conceived the book as celebrating all musics, and as contributing to a time in which the distinctions between musicology and ethnomusicology will no longer exist.

Latin America itself has a long and distinguished history of musical scholarship and documentation. Formal histories involving music undoubtedly existed among libraries kept by the Mexica, Maya, and others, but the Spanish burned their documents when they encountered them, and thus most information about them has been lost. Informal accounts of music making by Europeans date back to the first missionaries who came to the Americas in the fifteenth century, and others appear subsequently in the form of travel diaries, memoirs, and similar documents. Formal musicological studies began in earnest in the early twentieth century, as a rise in nationalist consciousness led to a gradual recognition of the importance of local repertoire. Pioneers such as Carlos Vega in Argentina, Mário de Andrade in Brazil, and Fernando Ortiz in Cuba provided research that has served as the foundation for subsequent publications in Latin America, the United States, and elsewhere. Many prominent researchers from the past hundred years are featured in the lists of additional bibliographic resources in the appendices, should you wish to consult them directly, and some are mentioned in individual chapters.

Musical study within Latin America continues to be influential today. The regional section of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music (IASPM América Latina), to cite one example, has become a vibrant forum for research, hosting annual conferences and lively listserve debates. Well established programs for the study of Latin American music in all its many permutations now exist in Rio de Janeiro and other Brazilian cities, in Bogotá, Mexico City, Santiago de Chile, and elsewhere. Musicologists continue to emerge throughout Latin America whose writings have broad international influence. One contemporary example includes Coriún Aharonián from Uruguay, cited in the references at the end of this essay.

One might think of music as resembling language in a certain sense: it consists of both sounds and meanings associated with sounds. Early studies of music among both musicologists and ethnomusicologists tended to prioritize the analysis of sound. Musicologists worked with excerpts from manuscripts or scores while ethnomusicologists transcribed folk melodies and analyzed scales, rhythms, and so on. Only since the 1970s have scholars paid more attention to the meanings associated with sound. They realize now that music is part of a broader cultural reality and that it can be studied as music but also “read” as a narrative or story.

The stories told by music revolve around issues of community, cultural negotiation or accommodation, gender relations, political dominance, protest, technological change, and so forth. Every instrument, rhythm, and melody with its unique history provides insights into particular countries, broad demographic trends, the inherited practices of distinct social groups, and their active re-interpretation of heritage. From this perspective, an instrument such as the timbales (discussed in Chapter 5) could be analyzed in terms of the rhythms played on it, or might be viewed as telling a story about the “Africanization” of European-style military percussion. This instrument developed out of European timpani drums used by black and mulatto Cuban soldiers in the nineteenth century. They began to use their sticks to play the sides of the drums as well as on the head, as is common in West Africa, to dampen the head with their hand as they played to alter the timbre, and so on. These techniques continue to be employed today.

Similarly, a dance band cumbia by Lucho Bermúdez (Listening Ex. 4.5) could be studied as musical composition or thought of as a text encoded with information about Colombian history. Songs such as this one make implicit reference to the history of Cartagena as a major slave port during the colonial era, to the gradual fusion of Indigenous and African musics into a host of folkloric genres on the Atlantic coast (commercial cumbia takes inspiration from music fusing Indigenous flute playing with African-derived drumming), to the stylization of such repertoire on the part of middle-class composers, and to the strong influence of big-band jazz in Latin America of the 1950s, among other things.

The many stories of Latin American music continue into the future; their sounds and meanings change frequently, responding to the preferences of new generations and to the ever-new situations that confront them. Given this, no textbook can hope to provide an exhaustive overview of Latin American music. Use the following chapters as a frame for thinking about the region and its heritage as you learn more about music you may be familiar with already and discover other sounds that are entirely new.

Aharonián, Coriún. 1992. Conversaciones sobre música, cultura e identidad. Montevideo, Uruguay: OMBU(wide-ranging essays that deal in part with the expression of Latin American identity through music).

Béhague, Gerard. 1991. “Reflections on the Ideological History of Latin American Ethnomusicology.” Nettl, Bruno and Philip Bohlman, eds., Comparative Musicology and Anthropology of Music. Essays on the History of Ethnomusicology, pp. 56-68. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press (discusses early biases on the part of music researchers and overall tendencies in scholarship).

Bethell, Leslie. 1998. A Cultural History of Latin America. Literature, Music and the Visual Arts in the 19th and 20th Centuries. New York: Cambridge University Press (covers major cultural trends and influential artists).

García Canclini, Néstor. 1995. Hybrid Cultures: Strategies for Entering and Leaving Modernity, transl. Christopher L. Chiappari and Silvia L. López. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press (discusses the hybridized nature of Latin American society).

Green, Duncan. 1997. Faces of Latin America. London: Latin American Bureau (a broad overview of Latin American history, culture, and society).

Nettl, Bruno. 2005. The study of ethnomusicology : thirty-one issues and concepts. Urbana, IL: Urbana : University of Illinois Press (provides an introduction to the discipline).

Rowe, William, and Vivian Schelling. 1991. Memory and Modernity. Popular Culture in Latin America. London: Verso (introduces the study of popular culture as a window into all of Latin American society).

Treitler, Leo. L. 1989. Music and the Historical Imagination. Cambridge, MA, 1989 (provides an overview of the discipline of musicology).