Throughout this textbook, the authors have noted European influences on Latin American classical music, not only in terms of the importation of the music itself but also the many European musicians who have emigrated to and worked in Latin America. European-derived classical music remains a vital force in Latin American culture, as reflected in the music curricula of Latin American conservatories and universities. These emphasize classical music, while local traditional and popular styles are generally taught and practiced in other contexts. For example, while there are major conservatories of music in Mexico City and Buenos Aires, over a thousand students are enrolled in the state-supported Universidade Livre de Música (Free University of Music) in São Paulo, where they study all kinds of popular music.

Classically trained performers and composers in Latin America get plenty of exposure to traditional and popular musics outside of the university or conservatory environment and frequently incorporate those influences into their music. In fact, nationalistic works by composers like Carlos Chávez, Alberto Ginastera, and Heitor Villa-Lobos draw heavily from vernacular musical traditions. Such composers are thoroughly embraced by the conservatories and universities in Latin America, and their music has acquired an almost official status as representative of their respective nations. In short, the European classical tradition has become a Latin American tradition as well, and governments and state agencies frequently support music written in this style even more enthusiastically than traditional or popular repertoire.

It is important to emphasize that cultural influences flow in multiple directions and that Latin America has had a great impact on the classical music traditions of Europe, as well as the United States. That impact continues unabated today. Indeed, just as Latin America has historically imported composers from Europe, it now exports many composers to Europe and the United States; moreover, many U.S. composers with Latin American ancestry embrace their heritage in composing classical music. This chapter briefly surveys the history of Latin American influence in classical music beyond Latin America, and then focuses on the lives and creative work of eight prominent Latin American and Latino/a composers of our own time.

Not long after the conquest, hybridized Latin American songs and dances blending European, African, and Indigenous elements were taken back to the Old World, where they underwent further changes and found their way from the streets of Spain to the courts of the European nobility. Dances of this sort dances included the zarabanda and chacona. Although no detailed information exists about their origins in the New World, we know that by the late sixteenth century they had become fashionable in Spain. These dances were lively and licentious, and the clergy at times attempted to suppress them, especially the chacona, notorious for its explicitly sexual movements.

During the early seventeenth century, versions of the zarabanda and chacona gained a following in other parts of Europe, especially Italy, where Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583-1643) wrote ciaconnas for harpsichord. Just as court musicians began to include this mestizo music in their repertoire and compose new pieces inspired by it, so dancer also adapted the steps to make them suitable for performance at court. Over time, the character of the genres changed, so that by the early eighteenth century, the Frenchified sarabande and chaconne had become stately and dignified rather than raucous. They were among the most prominent genres of music and dance during the entire Baroque period.

In the nineteenth century, the Latin American habanera (see chapter 5) gained widespread popularity among European audiences. One of the most influential composers of habaneras abroad was Sebastián Iradier (1809-1865), a musician from the Basque region of Spain. His many habaneras include such hits as “La paloma” (The dove) and “El arreglito” (The little arrangement). “La paloma” is among the most popular songs ever written, in Latin America and around the world; indeed, many people mistakenly think it is a folk song. Iradier composed it after visiting Cuba in 1861 but died in obscurity a few years later, never to learn how successful his composition would become. The French composer Georges Bizet (1838-75) made “El arreglito” famous in his 1875 opera Carmen, which tells the story of a Spanish Gypsy who lures an army officer to a life of crime, ultimately sealing her own fate as well as his. In the first act, Carmen sings her song “L’amour est un oiseau rebelle” (Love is a rebellious bird). Thinking “El arreglito” was a folk song, Bizet freely used it as the basis for his aria; however, he soon realized his error and gave Iradier credit in the score. Several other French composers wrote pieces in the style of the habanera, especially Emmanuel Chabrier (1841-94) and Maurice Ravel (1875-1937).

The habanera achieved popularity in Madrid as well, and many composers there wove its characteristic rhythms into their instrumental and stage works. Several piano pieces by Isaac Albéniz (1860-1909) are in the style of the habanera, including “Tango” from España: Seis hojas de álbum (1890). As late as 1932, Federico Moreno Torroba (1891-1982) composed the lovely “Habanera del Saboyano” for the first act of his zarzuela (Spanish operetta) Luisa Fernanda.

The Latin impact in classical music has also been noticeable among composers in the United States. One of the first to utilize Latin rhythms in concert music was the piano virtuoso and composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829-69). Born in New Orleans, Gottschalk studied in Paris and then spent considerable time concertizing in Cuba and Puerto Rico, where he came under the spell of the Caribbean’s musical charm. Many of his works exhibit the syncopated rhythms of Afro-Cuban and Puerto Rican music and dance, especially his Souvenir de Porto Rico, Marche des Gibaros, op. 31, for piano and orchestra.

In the twentieth century, leading American composers borrowing from the treasure trove of Latin music included Aaron Copland (1900-90), a close friend of Carlos Chávez. Some of Copland’s most famous compositions evoke the sights and sounds of Mexico, where he spent time traveling and establishing connections with local musicians during the 1930s and ’40s. Danzón cubano, El salón México, and Rodeo are three orchestral works that utilize the sounds of Mexican traditional music.

A student and friend of Copland was the conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein (1918-90), whose score for the hit musical West Side Story includes some of the most celebrated evocations of Latin American music, particularly the mambo that sets the scene for the dance party during which the star-crossed lovers first meet. Another number, “America,” uses the sesquialtera, or hemiola, rhythms that are a hallmark of Hispanic music. The lyrics express in an acerbic and even sarcastic manner the ambivalent feelings the Puerto Ricans harbor towards their new home, a land of promises not yet fulfilled.

Clearly, Latin American music of various kinds has had a continuous impact on classical music for hundreds of years. Commentary in the preceding chapters has also noted that, starting in the twentieth century, Latin American musical styles and Latin American composers themselves entered the mainstream of classical music and achieved international renown. Indeed, Villa-Lobos, Chávez, and Ginastera rank among the most prominent composers of the last century. That trend certainly persists today, and thus this essay considers actual composers who are making their presence felt abroad, through their music and their teaching. This discussion includes one composer who was born in the U.S. but has Peruvian ancestry and has spent considerable time in the Andes, and another who continues to work in Mexico but has spent years in Britain and the U.S. The others have all live and work in the U.S. or divide their time between the U.S. and their native countries. They are living proof that the impact of Latin America results not only from its vast musical heritage but also its outstanding composers.

In depth

The European-derived tradition of classical music is ubiquitous throughout Latin America, and numerous composers not only create new music but also teach in the regions many conservatories and universities. It serves a useful purpose here to list some ontinue to work in their native countries.

| Country | Composer |

| Argentina | Mario Davidovsky, Osvaldo Golijov, Marta Lambertini, Salvador Ranieri, Gustavo Santaolalla, Alicia Terzián |

| Bolivia | Augustín Fernández Sánchez, Oscar García, Ceésar Junaro, Juan Antonio Maldonado, Willy Pozadas, Cergio Prudencio |

| Brazil | Paulo Chagas, Rodrigo Cicchelli Velloso, Rodolfo Coelho de Souza, Paulo Costa Lima, Luis Carlos Csekö, Vânia Dantas Leite, Cirlei de Hollanda, Felipe Lara, José Augusto Mannis, Flo Menezes, Marlos Nobre, Ilza Nogueira, Jamary de Oliveira, Jocy de Oliveira, Tim Rescala, Marisa Rezende, Agnaldo Ribeiro, Ricardo Taccuchian, Roberto Victori |

| Chile | Juan Allende-Blin, José V. Asuar, Gustavo Becerra, Eduardo Maturana, Abelardo Quinteros, León Schidlowsky, Claudio Spies, Darwin Vargas |

| Colombia | Euclides Barrera, Eduardo Carrizosa, Jesús Pinzón, Luis Pulido, Francisco Zumaqu |

| Costa Rica | Jorge Luis Acevedo, Mario Alfagüell, Luis Diego Herra, Mauricio Pauly, William Porra |

| Cuba | Cálixto Alvarez, Efraín Amador, Héctor Angulo, Juan Blanco, Leo Brouwer, Carlos Fariñas, Sergio Fernández Barroso, Jorge Garciaporrúa, Tania León, José Loyola, Carlos Malcolm, José Angel Pérez Puentes, Juan Piñera, Magaly Ruiz, Roberto Valera, Aurelio de la Vega |

| Dominican Republic | José Antonio Molina, Miguel Pichardo-Vicioso |

| Ecuador | Milton Estévez, Gerard Guevara, Diego Luzuriaga, Mesías Maiguashca, Arturo Roda |

| El Salvador | Hugo Calderón, Jr., Victor Manuel López Guzmán, Gilberto Orellana Castro |

| Guatemala | William Orbaugh, Joaquín Orellano |

| Honduras | Norma Erazo, Sergio Suazo Lang |

| Mexico | Manuel de Elías, Julio Estrada, José Luis Hurtado, Federico Ibarra, Ana Lara, Mario Lavista, Arturo Márquez, Gabriela Ortiz |

| Panama | José Luis Cajar, Florentin Giménez, Marina Saiz Salazar |

| Paraguay | Nicolás Pérez González |

| Peru | Luis David Aguilar, Teófilo Alvarez, César Bolaños, José Carols Campos, Walter Casas Napán, Pozzi Escot, Celso Garrido-Lecca, Leopoldo La Rosa, Pedro Malpica, José Malsio, Alejandro Núñez Allauca, Francisco Bernado Pulgar Vidal, Edgar Valcárcel, Pedro Seiji Asato, Douglas Tarnawiecki, Jorge Villavicencio Grossman |

| Puerto Rico | Luis M. Alvarez, Rafael Aponte-Ledée, Ernesto Cordero, Ignacio Morales Nieva, William Ortiz, Francis Schwartz, Roberto Sierra, Raymond Torres Santos |

| Uruguay | Coriún Aharonián, León Biriotti, Sergio Cervetti, Antonio Mastrogiovanni, José Serebrier |

| Venezuela | Miguel Astor, Jorge Benzaquén, Tulio Cremisini, Paul Desenne, Carlos Duarte, Carlos García, Emilio Mendoza, Alfredo Rugeles, Ricardo Teruel |

One finds a great multiplicity of approaches to music composition among these composers, though many of them retain some element in their work that reflects their roots in Latin America. Latin American classical composers write tonal music, music reflecting the influence of popular culture, atonal and serial music, music for voices and for acoustic instruments, electronic music generated by synthesizers and computers, and multimedia works bringing together electronic and acoustic sounds as well as dance, theater, and the visual arts. They write this music for concerts, the stage, film, and the church. Thus, their compositions reach a wide and diverse audience; however, very experimental, avant-garde works, especially atonal music, usually appeal to a rather select group of listeners, who have both the openness and background to approach and appreciate this repertoire, which is often very challenging in its complexity.

The freedom a contemporary composer has to create according to her or his own vision is nearly complete and certainly greater than at any other time in music history. This freedom is made all the more noteworthy because of the emancipation of women in the world of professional music and their full participation as performers, conductors, and composers, something that had never before been the case in the male-dominated world of classical music from the Middle Ages onward (see Box 9.2).

The following survey of the contemporary scene in Latin/o American classical music considers the principal developments of the last thirty years or so, focusing on representative composers who work in the major media and genres of contemporary music, including acoustic, electronic, electro-acoustic, multi-media, and film music.

In depth

Women have not always occupied a central place in this textbook because of the marginalized position they traditionally held in society and the very limited professional opportunities available to them in the past. In the Middle Ages and well into the colonial period, women were not permitted to sing in church when men were present. This was in obedience to an injunction historically attributed to St. Paul in I Corinthians 14:34, stating that “women should keep silence in the churches.” Thus, women were not allowed to sing or even perform on musical instruments during worship services, except in convents or orphanages. Since it was in a church’s musical establishment that one got the training necessary for writing complex sacred polyphony, this effectively eliminated women from the ranks of Renaissance composers. Noblewomen could, of course, take private music lessons, but only to enhance their social graces. With the rise of opera in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and the increasing commercial demand for female voices, women began to appear more prominently in professional musical circles and to get the sort of training they needed to write music. But they were rarely accepted as professional composers. In the nineteenth century, female performers, such as Venezuela’s Teresa Carreño (see chapter 4), gained celebrity on both sides of the Atlantic, and they composed and even published piano pieces, songs, and chamber works; however, they were not taken seriously as composers of larger works, like symphonies and operas. Women were not thought to possess the intellectual gifts necessary for writing works of such complexity. In fact, the world most women inhabited remained bounded by domestic responsibilities until well into the twentieth century, when a rising tide of equal rights gave them greater access to musical education and professional opportunities, in both performance and composition. Today, some of the leading composers of our time are women, and they write in all genres, including symphonic works, and for all media, including electronic as well as acoustic. Three are featured in this chapter.

It should come as no surprise that a majority of contemporary composers continue to write for traditional instruments. First of all, they usually play these instruments themselves, especially piano, and feel a special rapport with them. Second, there is a continuing demand from performers and audiences alike for new acoustic music that can be presented in traditional concert venues. Composers have relatively few difficulties finding excellent pianists, violinists, or guitarists to play their new compositions. Finally, the resources of instruments like the piano, violin, and guitar have by no means been exhausted, and they present an ongoing challenge to composers to explore the sounds they can produce. Extended techniques are a crucial part of this exploration, as they represent non-traditional ways of playing traditional instruments, e.g., striking, blowing, plucking, or otherwise generating sound on them in ways earlier composers did not. Along with this increase in the resources available on acoustic instruments has come an expansion in the musical language itself, with the advent of microtonality, atonality, and new methods of notation.

I now consider a few composers whose acoustic compositions are on the cutting edge of contemporary music.

Gabriela Lena Frank (1972) is a composer in Northern California whose mother is Chinese-Peruvian and father, American, of Lithuanian-Jewish extraction. She grew up in the Bay Area but retains a close cultural and spiritual connection with Peru, where she has spent considerable time studying Andean folklore. Indeed, her music frequently incorporates Andean mythology, archeology, art, poetry, and music into Western classical forms, reflecting her Peruvian-American heritage.

Frank received her doctorate in composition from the University of Michigan in 2001. Although many composers today find it necessary to have a teaching position at a university in order to make a living, Frank has been able to support herself mostly by composing and performing. The roster of renowned concert artists who have played her music is large and includes such names as the Kronos Quartet, Cuarteto Latinoamericano, Chanticleer, the San Francisco, Chicago, Boston, Atlanta, Baltimore, and Philadelphia Symphonies, and cellist Yo Yo Ma. In 2009, she received a Guggenheim to work on an opera with Pulitzer-Prize winning playwriter Nilo Cruz about Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. Her list of honors also includes a Latin Grammy (2009) for Best Contemporary Classical Composition, Inca Dances, written for guitarist Manuel Barrueco and the Cuarteto Latinoamericano. In 2013, she was awarded the Medal of Excellence from the Sphinx Organization for outstanding young Black and Latino leaders in classical music. In 2015, she and her husband left San Francisco for Booneville, California, and two years later, she founded her own school, the Gabriela Lena Frank Creative Academy of Music, which enables emerging composers to work with leading performers. Her works are published by G. Schirmer in New York.

Frank continues to demonstrate that it is possible for modern composers to connect with concert audiences without compromising their artistic vision. Her Sonata andina (Andean Sonata) for solo piano is an excellent example of her skill in suggesting the sounds of folk instruments like the zampoñas and charango. The last movement takes inspiration from various live performances the composer heard in Peru shortly after her first extended visit to the country. She spins these impressions in a way that is exciting to her personally, yet still preserves a distinctly Latin spirit. She intends to stretch the definition of a “Latin sound” through everything she composes.

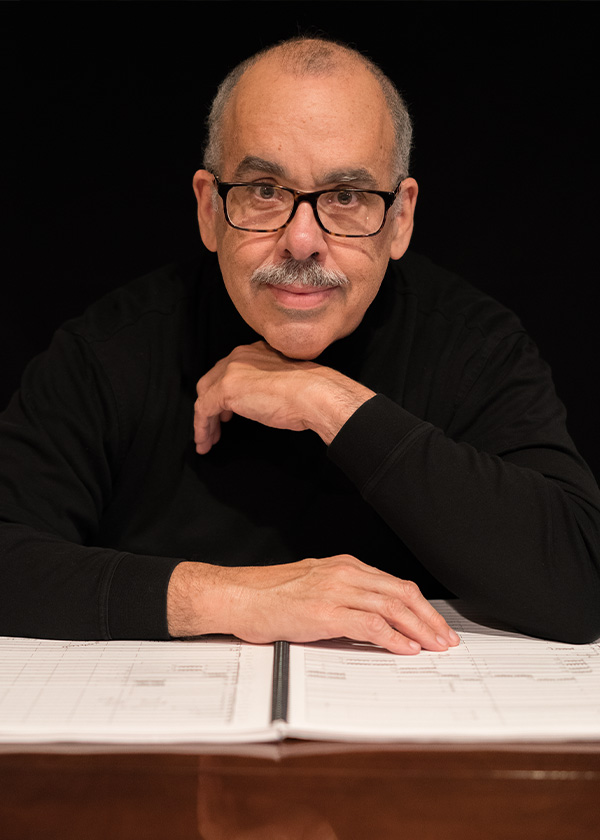

Tania León

Tania León In the post-WWII-era, American composers increasingly wrote music in the avant-garde style, without a tonal center or strong sense of pulse. It would seem that such a musical environment would not be conducive to the influence of Latin melodies and rhythms, but some contemporary composers have found a way to affirm their hispanidad in works that are otherwise quite rigorous in their modernity.

Tania León typifies a generation of composers determined to bridge a growing gulf between modern composers and audiences by writing music that is uncompromising in its originality and virtuosity while maintaining a profound connection with their musical roots. León (b. 1943) has African, Asian, and Spanish ancestry; originally from Cuba, she has lived and worked for many years in New York. A prolific composer, she writes for a very wide range of genres, including orchestral works, ballets, opera, percussion ensemble, and chamber music.

León is not only a composer but an accomplished conductor as well, having led orchestras in the U.S. and throughout Europe. She has taught at Harvard and Yale and is a Distinguished Professor Emerita at City University of New York. She has received numerous prestigious appointments, grants, and awards, including a Guggenheim (2007). The range of her activities is truly impressive and indicative of the way that Latinas are having an increasing impact on the cultural life of the U.S. For this reason, she has been featured in profile on all the major networks, as well as Univision and Telemundo. In 2010, she was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In 2019, the New York Philharmonic gave the world premiere of her orchestral work Stride, for which she received the 2021 Pulitzer Prize for Music. She was the first female African American to win that award. In 2022, she received a Kennedy Center Honor.

Her orchestral composition Horizons (1999) skillfully combines avant-garde techniques—complex rhythms and atonal passages—with elements of Latin American music: imitation of the claves in the piano part, and use of the harp, to suggest folk music. Though the harp is not common in Cuba today, León is clearly adopting a pan-Latin approach in her music. The same is true of her use of piano “claves,” which play rhythms of her own invention and are meant, like the harp, to suggest Latin America in general, insofar as instruments similar to the claves appear in many regional traditions, not just in Cuba.

Paul Desenne

Paul Desenne (1959-2023) was a native of Caracas, Venezuela. Son of a French father and American mother, he demonstrated unusual talent for music at an early age and eventually made his way to Paris, where he studied cello, composition, and music history, winning prizes for his cello playing. It was in Paris that he began to compose, and even his early works are suffused with the rhythms and melodies of South American music, particularly his native Venezuela, as well as neighboring Colombia and the Caribbean. In addition, Desenne’s compositions reflect his love of Renaissance and Baroque music.

He returned to Caracas in 1986 and established himself as a leading performer, teacher, and composer in the Venezuelan capital, which he used as a base for advancing what would become an international career. Indeed, his works have been performed throughout the Americas and Europe, and the list of ensembles and performers that have performed his music is impressive and includes the Orquesta Simón Bolívar, Boston Classical Orchestra, Bogotá Philharmonic, I Musici de Montréal, Miami Symphony, and Nederlands Blasers Ensemble, as well as the Fodor Quintet and Verdehr Trio. Among the eminent musicians who have conducted his music is Tania Léon (see above). In the fashion typical of most leading composers of our time, he relied on various foundations for financial support of his creative activities. Among the prestigious grants he received is one from the Guggenheim Foundation (2009). He was a Fellow at Harvard’s Radcliffe Institute (2010-11) and composer-in-residence with the Alabama Symphony Orchestra (2015-16).

Desenne’s works list is dominated by pieces for acoustic instruments, including chamber ensembles and symphony orchestra. Though evocations of the tango do not figure prominently in his output, still, among his most effective and evocative compositions is “Piazzolla bernitus” from Tango Sabatier, three tangos for arpegina (five- string viola) and piano, which reflects his strong sense of identity with South America in general, not just Venezuela. In the composer’s own words, this work is “an example of my composition process, which is often based on the use of pre-existing languages and musical codes of traditional Latin American . . . music to develop new forms . . . within the . . . parameters of those ‘popular’ or ‘traditional’ genres.” It is clearly intended as a tribute to the great tango performer and composer Astor Piazzolla (see chapter 7) in its expressive use of dissonance, varied rhythms, and in its introspective mood, though its formal structure is quite distinctive.

Roberto Sierra

Roberto Sierra was born in Vega Baja, Puerto Rico, in 1953. After completing studies at both the Conservatory and University of Puerto Rico, he did advanced work in composition with György Ligeti at the Musikhochschule in Hamburg, Germany. He first rose to prominence with his orchestral work Júbilo, performed by the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra at Carnegie Hall in 1987 (though the work had been premiered two years earlier by the Puerto Rico Symphony Orchestra in Puerto Rico). His compositions have since been performed throughout the U.S. and Europe, at festivals in New Mexico, Virginia, Puerto Rico, France, and Germany, by such ensembles as the New York Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Royal Scottish National Orchestra, BBC Symphony, as well as Spanish orchestras in Madrid, Galicia, Castilla-León, and Barcelona. In 2003, he received the music award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He was a Professor of Composition at Cornell University and is now retired.

Sierra’s Missa Latina “Pro Pace” (Latin Mass for Peace) was commissioned by the National Symphony Orchestra and the Choral Arts Society, both in Washington, D.C. It is scored for SATB chorus and orchestra, with soprano and baritone soloists. This expansive work is evidence of the enduring appeal of the texts of the Roman Catholic Mass, their ability to inspire composers to interpret and express their meaning through music. As the composer himself has stated,

My concept of the mass came from my own experience growing up as a Catholic

in a particular time and place. I still recall vividly hearing the mass in Latin in my

own town in Puerto Rico when I was a child. From the beginning, there was for

me a strong impression, which only deepened through the years: a sense of

mystery combined with both power and compassion in the ritual involving this

“dead language,” and hearing the Gregorian chants intoned by the priest.

Though the title signals that Sierra has indeed used the traditional Latin texts of the Mass, his setting is a very personal plea for peace, written during an especially difficult time of war in Iraq. It is basically tonal but makes highly expressive use of dissonance, orchestral color, and dramatic vocal writing to express its theme. Passages suggesting anguish and uncertainty contrast with others that very effectively convey the peace for which this Mass constitutes an extended prayer. Throughout the work, Sierra employs Afro-Caribbean percussion and syncopated rhythms, including 3 + 2 clave, giving this Mass a distinctly Latin flavor. As Sierra himself points out, “The orchestration reflects my interest relating to my ethnic background merged into the fabric of my music.” In 2009, the Naxos recording featured below was nominated for a Latin Grammy for Best Contemporary Classical Recording.

With the exception of the Introitus, Offertorium, and concluding “Pacem relinquo vobis . . . Alleluia,” Sierra’s Mass is a setting of the Ordinary, i.e., those texts that do not change from one liturgical season to the next. The seven movements of this Mass are:

Introitus (Introduction or Entrance, utilizing Sirach 36:18 and Psalm 121:1)

We focus on the final movement, whose text consists of a threefold statement of the same plea, with an important change in the third statement:

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis;

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis;

Angus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, dona nobis pacem.

Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us;

Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us;

Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, grant us peace.

Sierra follows this with an additional text,

Pacem relinquo vobis, pacem meam do vobis, dicit Dominus. Alleluia.

My peace I leave you, my peace I give you, saith the Lord. Alleluia.

An elaborate and extended setting of the Alleluia, featuring Afro-Caribbean syncopated rhythms and percussion instruments, brings this Latin Mass for Peace to a joyous and uplifting conclusion.

Tape recorders, synthesizers, computers, and electronic varieties of traditional acoustic instruments require specialized skills and knowledge to manipulate, but they offer virtually unlimited possibilities in sound generation and control. Many composers have written music using either purely electronic means or combining electronic instruments with traditional acoustic ones, to create electro-acoustic works. The segment below considers two leading composers in this fascinating area of musical creativity.

Gabriela Ortiz

Gabriela Ortiz s among Mexico’s leading composers today, one whose style combines elements of classical and folk music, as well as rock and jazz. Highly versatile, she writes for acoustic instruments as well as electronic media, concert music, music for modern dance, and even a “video-opera,” Unicamente la verdad (Only the truth), of 2010. Ortiz was born in Mexico City in 1964, and both of her parents were musicians in the famous folk-music ensemble Los Folkloristas. After completing music studies at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and Escuela Nacional de Música, she received a scholarship in 1990 to further her studies in England, completing her doctorate in composition at University of London in 1996.

Her music exhibits a high degree of sophistication and complexity, yet through its connection with vernacular music, it possesses the sort of immediacy and spontaneity that make it accessible and appealing to a larger public. Her compositions have been commissioned, premiered, or performed by ensembles throughout the Americas and Europe, such as the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Kronos Quartet, Orquesta Simón Bolívar, Cuarteto Latinoamericano, Mexico City Philharmonic, and the BBC Scottish Symphony, to name a few. She has won numerous awards, including a Guggenheim fellowship and grants from the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations. She has taught at the University of Indiana and is now on the composition faculty of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma in Mexico City.

Ortiz writes principally for acoustic media, and one of her most outstanding recent contributions to that repertoire is the string quartet Altar de Muertos (Altar of the Dead), composed for the Kronos Quartet. However, one of her electronic works will be examined here, Five Micro Études for Solo Tape (1993). An etude is historically a piece of music intended to explore and develop particular aspects of instrumental technique. Continuing this tradition, Ortiz’s Micro Études represent a novel exploration of the potential of electronically generated and recorded sound. Sounds are produced on a synthesizer and then recorded and manipulated on tape to create completely distinctive textures, colors, and rhythms. The fifth and final Étude in this collection evokes the sounds of wind chimes and bells.

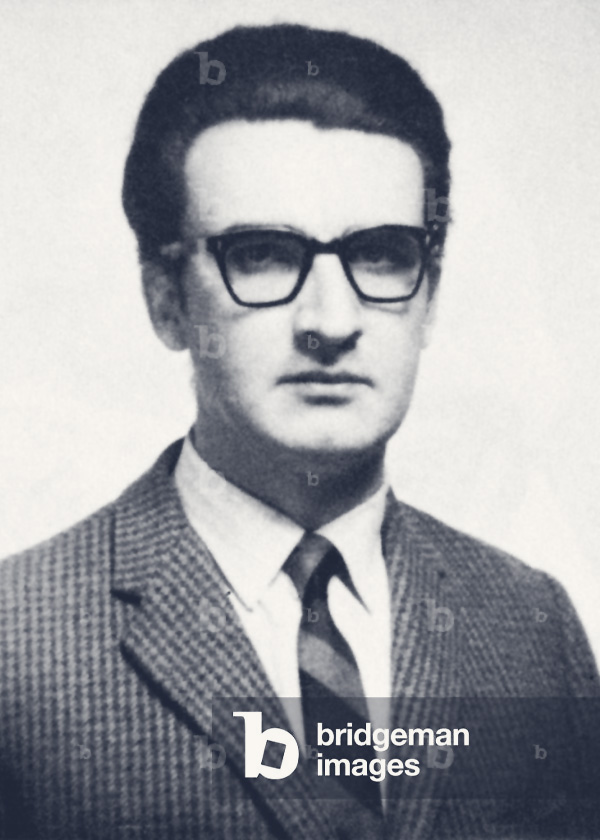

Mario Davidovsky

Mario Davidovsky (1934-2019) was a U.S. composer of Argentine birth. He was born in the province of Buenos Aires, the son of Lithuanian-Jewish parents. At age 7 he began his musical studies on the violin, and he started composing at age 13. After graduating from the University of Buenos Aires, he immigrated to the United States in 1960 to pursue his studies and career, settling in New York City and becoming associate director of the Electronic Music Center run by Columbia and Princeton. His electro-acoustic compositions earned him an international reputation, especially his series of Synchronisms, the sixth of which won a Pulitzer Prize in 1971. In 1982, he was elected as a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He became a professor of music at Harvard in 1994 and taught at other leading music schools, including the University of Michigan and Yale.

For Davidovsky, electronic generation of music allowed him to control the basic elements of musical sound, e.g., the beginning, duration, and end of each sound, along with tone color and intensity. Moreover, he could splice magnetic tape to assemble sounds in any order or sequence he desired. Each composition represented a new universe of sound that he himself created.

In the 1970s, however, Davidovsky returned to writing music for traditional instruments and voice, and most of his works since that time were acoustic, not electronic. His Synchronisms No. 10, composed in 1992, is an exception to this trend, as it brings together guitar with prerecorded electronic sounds. Not only does the tape present many distinctive electronic elements, but the guitarist is also called upon to use extended techniques to increase the range of the guitar’s expressive potential. These techniques include striking the instrument and rapidly brushing the strings with the fingers. The musical language is atonal, without a discernible meter or beat sense. In these respects, it is characteristic of much post-war avant-garde music.

Multi-media is a largely self-explanatory term. It refers to the use of multiple media to create a total work of art comprising music and other arts such as dance, film, visual art, speech, acting, and electronic media.

Paulo C. Chagas

Paulo C. Chagas (b. 1953) has had a distinguished international career, beginning in his native Brazil, where he received bachelor’s and master’s degrees in music, then moving on to Germany and Belgium, where he received his doctorate in musicology. He is now in California, as Professor of Composition at the University of California, Riverside (2004-present), where he founded and directs the Experimental Acoustic Research Studio. He has composed over one hundred works, for multimedia, orchestra, instrumental and vocal ensembles, as well as electronic and computer music. In fact, he specializes in the use of digital technology in music composition. His works have been performed in Europe, the United States, Asia, and Latin America to both public and critical acclaim. He is also a productive scholar and has written numerous articles, book chapters, and books in English, French, German, and Portuguese.

Chagas worked for ten years (1990-99) as Sound Director of the Studio for Electronic Music of the WDR (West German Radio and Television Broadcasting), where he conducted extensive research into electronic and computer music, algorithmic composition, interactivity, multimedia, and the spatial arrangement of recorded sound. He has also written music software and special computer applications for musical analysis and composition; in addition, he researches gesture and interactivity, involving the use of sensors and the relationship between sound, image, and movement.

His techno-opera RAW was premiered by Opera Bonn in 1999. The title is WAR spelled backwards, and in this ambitious work, Chagas brings together a wide range of electronic and acoustic instruments, as well as various other media, to explore themes of violence. Chagas was himself the victim of violence when, at age 17, he was arrested and tortured by the military dictatorship in Brazil in 1971 for collaborating with opposition groups fighting for democracy. He describes his ordeal in the following way:

I was put in the “fridge,” a small room, refrigerated and acoustically isolated, and

completely dark and cold. Various noises and sounds—howling oscillators,

rumbling generators, distorted radio signals, motorcycles, etc.—shot from

loudspeakers hidden behind the walls. Incessantly, the electronic sounds filled

the dark space and overwhelmed my body for three long days. After a time, I lost

consciousness. This auditory and acoustic torture was then a recent development,

partially replacing traditional methods of physical coercion that killed thousands

in Latin American prisons between the 1960s and 1990s. Such sounds injure the

body without leaving any visible trace of damage. The immersive space of the

torture cell, soundproofed and deprived of light, resonates in my memory as the

perfect environment for experiencing the power of sound embodiment.

He was freed from prison only after the intervention of a military officer who was a friend of his parents. His works continue to explore themes of power, violence, and control, using the latest technology and theoretical approaches.

The main characters in the opera are the Yoruba god of war, Ogun, and his Three Wives, as well as a General and a Soldier. Their respective texts are taken from traditional Yoruba poetry, the writings of the nineteenth-century Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz, and three books by author Ernst Jünger dealing with the First World War. Chagas is clearly drawing on his personal experience in this work, as he grew up in Salvador, Bahia, where the presence of Afro-Brazilian religion, especially Candomblé and its associated deities, is very strong (see Chapter 6). The influence of African and Afro-Brazilian music is prominent in RAW; though Chagas has invented most of the rhythmic material himself, he employs a 12/8 bell pattern used by the Ewe people of southern Ghana. His long residence in Germany inspired him to depict war and religion as universal features of human society. The performing forces are truly impressive in number and variety and include electronic keyboards, computers, synthesizers, and a large battery of percussion instruments, as well as five singers and a dancer. The staging includes a bank of televisions tuned to real-time programming.

The seventy-five-minute opera itself does not tell a story or have a plot. Rather, it consists of sixty separate scenes, each with its own distinctive textual, musical, and dramatic character, but all dealing with the topic of war. The ten-minute excerpt on the website features scenes 20-21, 50-51, 53, and 60.

Writing music for film requires a great deal of versatility, because the composer needs to draw on the widest variety of media and musical styles to convey, complement, or even contradict the drama onscreen. This can involve all of the techniques encountered above, as well as the ability to write in a variety of styles, both historical and contemporary, and to cross from folk to popular to classical styles with ease.

Among the most successful composers of film music today is Gustavo Santaolalla (b. 1951) of Argentina, one of only four composers ever to win back-to-back Oscars for his music. In 2005, he won the Academy Award for Best Original Score for Brokeback Mountain. He won again the following year for Babel. In addition, he has won other prestigious awards for his film scores and other recordings, including Grammy, Latin Grammy, and a Golden Globe in 2006 for Best Original Song, “A Love That Will Never Grow Old” from Brokeback Mountain.

In the context of this chapter, Santaolalla’s career is somewhat unusual. Like Heitor Villa-Lobos (see chapter 6), he got his start playing popular music and learning from his immediate musical environment. Unlike the other composers discussed in this chapter, he did not attend a music conservatory or university to study composition. Nonetheless, he is actively and successfully involved in both popular and classical music. In fact, it is his remarkably diverse musical background and versatility that have enabled him to succeed as a film composer.

As a young man, he founded the group Arco Iris (rainbow), which pioneered a fusion of rock with Latin American folk music as part of the rock nacional movement in Argentina (see chapter 7). He moved to Los Angeles in 1978, and he remains based there today. In addition to performing with rock groups, he has cut several solo albums. His innovative blending of rock with the sounds of Latin American folklore, especially that of the Andes, is his distinguishing trait as a composer and performer. It is this style that has found a place in his music for both television, film, and even video games.

He is active as a producer, having co-produced the Kronos Quartet’s Nuevo, an album that celebrates the musical heritage of Mexico. In addition, Santaolalla has collaborated with Argentine composer Osvaldo Golijov and soprano Dawn Upshaw, who commissioned the opera Ainadamar, based on the murder of Spanish poet Federico García Lorca, and Ayre, a collection of folk songs, in which Santaolalla performs with a group called The Andalucian Dogs. He was inducted into the Latin Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2015, and in 2023, he won a Primetime Emmy Award in the category of Outstanding Composition for a Series: The Last of Us: Long, Long Time

In 2004 Santaolalla won the BAFTA (British Academy of Film and Television Arts) Award for Best Film Music for his score for The Motorcycle Diaries (Diarios de motocicleta), which tells the story of a young Che Guevara on his motorcycle tour of South America. The poverty and injustice he encounters transform his worldview and his life. Santaolalla’s score often draws on folk music for inspiration. Such references in the music not only establish the setting of the action but also represent the culture of the people Che encounters and to whose cause he will commit himself. In the overture to the movie, the composer plays guitar and is accompanied by members of the Argentine rock group Bersuit.

It is clear throughout this book that the boundaries separating folk, popular, and classical styles are very permeable, that for centuries performers and musicians have routinely crossed these borders in search of new sounds and means of expression. The composers highlighted above are no exception to this rule, and even in the context of very new music that challenges our ability to listen and respond, they have consistently drawn upon instruments, sounds, and traditions that we recognize. Their art remains grounded in what is familiar, even as it presents us with types of musical expression that may seem strangely, even wildly, unfamiliar. In short, Latin American composers possess an inexhaustible storehouse of musical inspiration to draw upon. Their music will continue to surprise, challenge, and move us for a long time to come.

Gidal, Marc M. “Contemporary ‘Latin American’ Composers of Art Music in the U.S.: Cosmopolitans Navigating Multiculturalism and Universalism.” Latin American Music Review 31/1 (spring/summer 2010): 40-78

Lundy, A. “Conversations with Three Symphonic Conductors: Dennis DeCoteau, Tania León, Jon Robinson.” Black Perspective in Music 16/2 (1988): 213-226.

Lusk, J. “The Last Tango (interview with Gustavo Santaolalla).” fRoots 30/5 (November 2008): 43-45

Madrid, Alejandro. Tania León’s Stride. A Polyrhythmic Life. Series: Music in American Life. Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2021.

Rivera, José. “Roberto Sierra’s Missa Latina (Pro Pace).” Choral Journal 50/8 (March 2010): 6-23.

Slayton, Michael. Women of Influence in Cpntemporary Music: Nine American Composers. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2011.

Starobin, David. “A Conversation with Mario Davidovsky.” Guitar Review, n92 (winter 1993): 5-8.

Title of piece: Sonata andina (Andean Sonata), fourth movement

Date of composition: 2000

Date of performance/recording: 2000

Composer: Gabriela Frank

Performer/Instruments: performed on piano by the composer

Form: free alternation of various themes and sounds derived from Peruvian folk music

Rhythm: variable meters and complex rhythms drawing both on folklore and the classical avant-garde

What to Listen for:

Time

0:00 - 0:37

Track

Opening vamp

Description

Impression of a group of guitarists, charanguistas (charango players), and tamboristas (drummers) strumming and drumming to signal the opening of the piece. The open strings of the guitar appear in the first couple of bars and then the harmony diverges, displaying a wide variety of chords for the rest of the piece. At 0:26, the charanguistas gradually fade out, just as a rhythmic groove begins to enter at 0:38

Time

0:38 - 1:07

Track

Golpe section 1

Description

Quickly repeated chords in the right hand support a melody line that is punctuated by a simulation of guitar golpes, when a guitarist strikes the strings with the flat of the hand. These golpes happen at roughly two-second intervals from 0:43 to 0:56

Time

1:08 - 1:10

Track

Transition 1

Description

Sesquialtera appears for the first time. The notes of this melody correspond to the pipes of the zampoña: E-G-A-B-D-E. This is against the left-hand arpeggio from Transition 1. It is repeated, with new ornamentation, at 1:19

Time

1:28 - 2:07

Track

Zumballyu section

Description

The spinning figure in the left hand is inspired by a child’s top from the Andes, the zumballyu. This figure will come back later in the Vendaval Section. At 1:34, another zampoña melody (Zampoña melody 2) sounds in the right hand, a skipping light phrase. Parts of the melody mimic sliding the mouth over several pipes in one breath. At 1:53, the whole idea repeats again, with new harmony.

Time

2:08 - 2:10

Track

Transition 2

Description

This transition is in sesquialtera and will come back later.

Time

2:11 - 2:45

Track

Marimba-inspired section

Description

Although really a Central American and Ecuadorian instrument, Peruvian musicians also play the marimba, striking the same keys over and over again, with both mallets at once or alternating the notes and rhythms. There are two basic rhythmic patterns here: the first at 2:11-2:17 and 2:24-2:31; and the second at 2:17-2:24 and 2:31-2:38.

Time

2:46 - 3:10

Track

Reprisal of Golpe section #1

Description

A return of the first Golpe Section in a different key.

Time

3:11 - 3:16

Track

Reprisal of Zampoña melody 1

Description

The melody from before is now in G minor and in strict imitation between the two hands.

Time

3:17 - 3:21

Track

Reprisal of Transition 2

Description

Same as before but transposed to another key.

Time

3:22 - 4:03

Track

Vendaval section (vendaval is a strong wind)

Description

A gusty storm (vendaval) inspires this section, and the moving line in the right hand is the left hand zumballyu figure from before. The left hand features the figure from Transition 1 and the Zampoña melody 1 sections. This section has little bits spliced into it that come from the Zampoña melody 1.

Time

4:04 - 4:10

Track

Long transition into coda

Description

Inspired by the marimba patterns presented earlier, which build up to the return of the opening guitar-charango-drum vamp.

Time

4:11 - end

Track

Reprisal of opening vamp

Description

The very last dying figure in the final bar is an echo of Zampoña melody 2, originally accompanied by the zumballyu but now only by a low trill in the left hand—a final drum roll.

Title of piece: Horizons

Date of composition: 1999

Date of performance/recording: 1999

Composer: Tania León

Performer/Instruments: North German Radio Symphony, conducted by Peter Ruzicka

Form: free form based on evolving melodic ideas

Rhythm: lively tempo using complex repeating rhythm patterns as basis for melodic

overlay; juxtaposition of different tempos between piano “claves” and orchestra

Time

0:00 - 1:04

Track

First section

Description

Very brief clarinet solo, followed by lively outbursts in other woodwinds, suggesting bird songs; raucous brass lines add to the excitement.

Time

1:05 - 1:25

Track

Description

Bird trills initiate a calmer mood

Time

1:26 - 1:47

Track

Description

Violent outburst in brass and percussion.

Time

1:48 - 2:29

Track

Description

Piano plays repeated rhythmic patterns in imitation of claves; followed by loud and dense writing for brass, percussion, and piano.

Time

2:30 - 2:55

Track

Description

Timpani solo.

Time

2:56 - 3:24

Track

Description

Piano introduces another clave rhythm, over complex and strident rhythms in the percussion; followed by melodic ideas in winds and strings.

Time

3:25 - 3:37

Track

Description

Explosion of brass and percussion

Time

3:38 - 3:53

Track

Description

Folk-like melody in flute, performed with an extended technique called flutter tonguing.

Time

3:54 - 4:04

Track

Description

Further outburst in brass and percussion interrupt flute solo.

Time

4:05 - 5:56

Track

Adagio section

Description

Serene slow passage in shimmering strings, consisting of long-drawn- out harmonies, played softly. Piano interjects dissonant notes at various points and with increasing frequency, joined by brass.

Time

5:57 - 6:23

Track

Transition

Description

Serene atmosphere disintegrates as dissonant outbursts in piano and brass take over.

Time

6:24 - 6:48

Track

Quasi return to main section

Description

Bird songs in woodwinds reappear, over a clave figure in piano.

Time

6:49 - 7:10

Track

Description

Lengthy clarinet solo develops very opening idea.

Time

7:11 - 7:37

Track

Description

Wild eruptions in winds, brass, percussion, and piano.

Time

7:38 - 7:49

Track

Description

Clave rhythm in piano reappears.

Time

7:50 - 8:03

Track

Description

Tapering off in intensity.

Time

8:04 - 8:17

Track

Conclusion

Description

Harp appears over piano clave rhythm and percussion, playing chords in imitation of Latin American folk harp.

Time

8:18 - end

Track

Description

Gyrating bird-song clarinet solo over piano, percussion, and harp brings work to a colorful finish.

Title of piece: “Piazzolabernitus” from Tango Sabatier, Three Tangos for arpegina [five-

string viola] and Piano

Date of composition: 2003

Date of performance/recording: 2003

Composer: Paul Desenne

Performer/Instruments: Jean-Paul Minalli, arpegina; Veronique Goudin, piano

Form: free form with repetition and development of melodic ideas

Tempo: moderate duple meter, consistent with characteristic of the tango

Time

0:00 - 0:46

Track

Arpegina and piano present main theme in opening section

Description

Slow, mournful, in subdued tempo rhythm; tonal, with very dissonant elements.

Time

0:47 - 1:50

Track

Both instruments present a new idea in the opening section

Description

Introduction of a strong tango rhythm in the bass register of the piano; increasingly sense of direction in the melodic line.

Time

1:51 - 2:19

Track

Development of themes

Description

Strident chordal interjections in piano signal new section; jagged, angular rhythms in both instruments.

Time

2:20 - 3:39

Track

New section based on new melodic ideas, though clearly related to earlier themes

Description

Sudden decrease in tension and dynamic level; mellow, more introspective, lyrical, relatively consonant; dialogue between arpegina and piano.

Time

3:40 - 3:56

Track

Development of ideas

Description

Increase in rhythmic agitation dynamic motion, and dissonance.

Time

3:57 - 4:46

Track

Description

Decrease in agitation and return to introspective mood.

Time

4:47 - 5:40

Track

Return of opening section

Description

Reappearance of tango rhythm.

Time

5:41 - 6:05

Track

Development of main theme

Description

Acceleration in tempo and rhythms.

Time

6:06 - end

Track

Conclusion

Description

Mournful and languid.

Title of piece: “Agnus Dei,” from Missa Latina “Pro Pace”

Date of composition: 2003-05; premiered 2006

Date of recording: 2008

Composer: Roberto Sierra

Performers/Instruments: Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, conducted by Andreas Delfs, with Heidi Grant Murphy, soprano, and Nathanial Webster, baritone

Form: binary form, featuring tonally and metrically ambiguous setting of the Agnus Dei, followed by a contrastingly tonal and upbeat Alleluia

Tempo: Moderate triple meter, but without a strong sense of beat until the Alleluia (in 4/4)

Time

0:00 - 0:51

Track

First Agnus Dei

Description

Baritone sings an extended melisma on the opening syllable, while winds and brass weave lines around the voice; an air of mystery pervades this section, especially in the use of Middle Eastern-sounding minor scales.

Time

0:52 - 1:15

Track

Description

Soprano and choir join baritone in completing the first line of text.

Time

1:16 - 1:37

Track

Description

Choir repeatedly intones “miserere nobis” (have mercy upon us), soon joined by orchestra and swelling to a climax, followed by a sudden drop in tension to prepare for line two.

Time

1:38 - 1:58

Track

Second Agnus Dei

Description

Soprano now sings Agnus Dei, accompanied by orchestra and chorus.

Time

1:59 - 2:07

Track

Description

Soprano and chorus repeatedly intone “peccata” (sins).

Time

2:08 - 2:50

Track

Description

Baritone enters, singing “miserere nobis,” which is taken up by the choir and soprano, accompanied by orchestra.

Time

2:35 - 2:50

Track

Third Agnus Dei

Description

Chorus sings last statement of Agnus Dei.

Time

2:51 - 3:10

Track

Dona nobis pacem

Description

Baritone now concludes with the words “dona nobis pacem” (grant us peace), soon joined by choir.

Time

3:11 - 5:18

Track

Pacem relinquo vobis

Description

Rapturous and dramatic soprano solo, eventually accompanied by chorus, presents the additional line of text, emphasizing the word “pacem.”

Time

5:19 - 5:40

Track

Transition

Description

Piano notes in low register, with timpani and suspended cymbal, sound an ominous note but in fact herald the Alleluia, announced in the baritone and soon joined by the choir and brass instruments.

Time

5:41 - 6:56

Track

Alleluia

Description

Afro-Caribbean percussion and syncopated rhythms, now in quick duple meter, accompany the soloists, chorus, and orchestra in an upbeat celebration of praise.

Time

6:57 - end

Track

Conclusion

Description

Dance-like Alleluia becomes a triumphal hymn, with soloists and chorus singing together.

Title of piece: Five Micro Études for Solo Tape, No. 5

Date of composition: 1993

Date of performance/recording: 2001 (Alma Latina, Lontano Records, LNT119)

Composer: Gabriela Ortiz

Performer/Instruments: Gabriela Ortiz, using synthesizer and magnetic tape

Form: free form exploring various sounds suggestive of everyday life and music

Rhythm: freely expressive and complex, without any beat sense

Time

0:00 - 0:09

Track

Introduction

Description

Strident opening sounds taper off into silence, preparing for a new sound.

Time

0:10 - 0:34

Track

Sound 1

Description

Wind-chime-like sounds create a pleasantly whimsical effect, joined by the tinkling sound of small bells at 0:22.

Time

0:35 - 0:41

Track

Transition

Description

Increasing intensity leads to a crash-like climax at 0:41.

Time

0:42 - 0:58

Track

Sound 2

Description

Sound resembling the pealing of church bells becomes prominent, quickly fading out.

Time

0:59 - 1:15

Track

Sound 1

Description

The sound of wind chimes and tinkling bells returns, growing in intensity.

Time

1:16 - 1:25

Track

Transition

Description

Entrance of a straight tone heralds the arrival of a new sound.

Time

1:26 - 1:33

Track

Sound 3

Description

Ping-pong-like sound, with sudden increase in intensity at 1:34.

Time

1:34 - 1:46

Track

Description

Deepening of the ping- pong effect and increasing rapidity of sounds prepares for arrival of a new effect.

Time

1:47 - 1:50

Track

Transition

Description

Climax and rapid decrease in intensity.

Time

1:51 - 2:03

Track

Sound 4

Description

Drawn-out sonar-like pings, with rapid cricket- like sounds in the background.

Time

2:04 - 2:10

Track

Transition

Description

Increasing intensity, with cricket-like sounds coming to the fore along with a sound resembling a small gong.

Time

2:11 - end

Track

Conclusion

Description

Complex rhythms of the cricket sound begin to resemble castanets and travel from left to right speakers. Gradually fades to nothing.

Title of piece: Synchronisms No. 10 for Guitar and Electronic Sounds

Date of composition: 1992

Date of performance/recording: 2000 (Flashbacks: Music by Mario Davidovsky, Bridge Records, Bridge 9097)

Composer: Mario Davidovsky

Performer/Instruments: guitarist David Starobin with prerecorded electronic sounds

Form: free form, with basically two sections, the first featuring guitar alone, followed by a longer section introducing tape-recorded sounds

Rhythm: freely expressive and complex, without any beat sense

Time

0:00 - 2:27

Track

Guitar alone

Description

Points of sound in free rhythm, including use of strumming, plucking, harmonics, and strings slapping against fingerboard. Atonal and dissonant throughout.

Time

2:28 - 2:29

Track

Silence

Description

Time

2:30 - 2:39

Track

Guitar alone

Description

Rhythmically animated melodic line.

Time

2:40 - 2:43

Track

Silence

Description

Time

2:44 - 3:31

Track

Guitar alone

Description

More isolated points of sound, strident and percussive at times, starting out agitated and becoming increasingly calm and reflective at 3:02.

Time

3:33 - 3:35

Track

Silence

Description

Time

3:36 - 4:29

Track

Guitar alone

Description

Continued reflective with use of flesh of right-hard fingers to brush the strings rapidly.

Time

4:30 - 4:36

Track

Silence

Description

Longest silence yet punctuated by a single chord at 4:33.

Time

4:37 - 6:24

Track

Taped electronic sounds begin and interact with the guitar

Description

Sustained sounds in the tape recording, gradually becoming agitated.

Time

6:25 - 6:39

Track

Guitar and tape

Description

Rapid escalation from soft to loud, with violent outburst in both tape and guitar starting at 6:35.

Time

6:40 - 7:24

Track

Description

Return to relative calm with occasional outbursts in taped sound; use of repeating rhythmic patterns.

Time

7:25 - 7:59

Track

Description

Peaks and valleys of loud, dissonant sounds, building to climax.

Time

8:00 - 8:16

Track

Description

Explosion of rhythmic agitation and dissonance at intense dynamic level.

Time

8:17 - 9:16

Track

Description

Tapering off in intensity, then building up again.

Time

9:17 - end

Track

Description

Final climax and dying out.

Title of piece: RAW, a Multimedia Opera (ten-minute excerpt, featuring six scenes)

Date of composition: 1999

Date of performance/recording: 1999

Composer: Paulo C. Chagas

Performer/Instruments: Opera Bonn

Form: free form, following the meaning and structure of the texts themselves

Rhythm: free and complex rhythms, usually without regular beat sense, except in passages based on repeated patterns derived from West African drumming

Time

0:00 - 1:40

Track

Scene 20

Description

The Soldier sings of the barbarity of war, while Ogun (the dancer in blue) dominates the scenery on his platform. The televisions are tuned to real-time programming, which just happened at the time to be showing the NATO bombing attack on Serbia. The persistent syncopated rhythm throughout this scene is derived from West African drumming.

Time

1:41 - 2:42

Track

Scene 21

Description

The General sings texts taken from the writings of Clausewitz, who is famous for remarking that “war is a continuation of politics by other means” (this quote actually appears in the text of scenes 55-57 and 59). The percussive rhythm changes in this scene from the pattern in Scene 20.

Time

2:43 - 4:49

Track

Scene 50

Description

Soldiers move in the manner of an exercise video, adding a grim sense of ironic humor to the scene, which features the writings of Clausewitz. They dance to constantly shifting rhythms in 7/8 meter.

Time

4:50 - 5:53

Track

Scene 51

Description

The sound of a choir is actually produced on a synthesizer. This accompanies the Three Wives of Ogun as they mill about the soldiers.

Time

5:54 - 7:37

Track

Scene 53

Description

Televisions tuned to various shows in real time. The three wives comfort Ogun, dressed as a businessman. The upper torso and head of the Soldier appear on the table behind, and he also sings.

Time

7:38 - end

Track

Scene 60 (conclusion)

Description

The end of the opera features the Three Wives and soldiers singing “save me.” The Soldier sings of his insatiable thirst for whiskey, just before he is to die in combat.

Title of piece: Overture to The Motorcycle Diaries (Diarios de motocicleta)

Date of composition: 2004

Date of performance/recording: 2004

Composer: Gustavo Santaolalla

Performers: Gustavo Santaollala, Aníbal Kerpel, Braulio Barrera, Don Markese, and Javier Casalla

Form: binary form, A-A’, in which the A section is restated in a varied manner

Rhythm: slow triple meter with syncopated rhythms suggesting indigenous music

Time

0:00 - 0:14

Track

Section A

Description

Suggestion of folk music through syncopated rhythmic opening played on a charango.

Time

0:15 - 0:29

Track

Description

Entrance of electric guitar playing repeated chord progression over rhythmic accompaniment.

Time

0:30 - 0:44

Track

Description

Addition of flute line to harmonic progression.

Time

0:45 - 1:27

Track

Description

Strident, bold chords in the guitar increase intensity.

Time

1:28 - 1:41

Track

Section A’

Description

Sudden decrease in intensity as all parts drop out, except opening syncopated rhythm on the charango.

Time

1:42 - 2:23

Track

Description

Return of all parts at maximum intensity. Violin and bombo prominent.

Time

2:23 - 2:31

Track

Description

New melodic idea in flute and violin.

Time

2:32 - end

Track

Description

Final cadence as music fades away, to the syncopated rhythm in the charango and long notes in violin and flute.