This chapter discusses recent trends in Latin American popular music and Latino popular music (Latinos are people of Latin American heritage who live in the United States). Since 2000, Latin American and Latino popular music are so deeply intertwined that it has become increasingly difficult to draw a clear line between them, as the songs considered here illustrate. Strikingly, the United States is today the second-largest consumer market for Latin American music after Brazil. The market for regional Mexican music (an umbrella term that includes styles like norteña, banda, and ranchera) is larger in the United States than in Mexico itself! Accordingly, the production center for regional Mexican music is now in Southern California, not Northern Mexico. And the largest market for Dominican bachata is not on the island of Hispaniola but on the East Coast, largely due to the increase in Dominican immigration and the popularity of Aventura, a Dominicanyork band from the South Bronx.

Not only is the United States an important consumer of “Latin/o American” music (this term will be used when it is appropriate to encompass Latin Americans, U.S. Latinos, and music in Spanish), but it is also the most prolific production center for Spanish-language popular music, the vast majority of which is produced by the three major international recording labels (Warner, Sony, and Universal), and distributed by streaming services like Spotify, Apple Music, and YouTube. Each of these labels has a subsidiary that oversees music for the Latin American and Latino markets, creating alliances with local record companies. Some artists based in Latin America travel to the United States to collaborate with producers and take advantage of cutting-edge studio technology. Some relocate permanently to the United States to internationalize their careers (Miami remains the preferred hub for artists with hemispheric appeal). And some Spanish-language pop stars are U.S.-born Latinos who are bicultural, and equally comfortable in U.S. and Latin American cultures.

One of the most salient features of twenty-first-century Latin/o American popular music is its hybridity. Hybridity, the mixing of various elements, is certainly not unique to Latin American music. All popular music worldwide results from combinations of features from multiple sources from the distant and recent past. What is noteworthy about recent Latin/o American popular music is that it embraces hybridity as an aesthetic. More often than in Anglo pop music, Latin/o American artists are likely to combine the local with the global in their hit songs. Mexican artist Peso Pluma may rap over a standard and acoustic corrido, and Los Angeles band Ozomatli may mix a shout-out in Jamaican dancehall style with tejano accordion and Indian tabla. The songs discussed in this chapter illustrate that Latin/o Americans are in dialogue not only with other nations from the Americas but also with the rest of the world

An important inspiration for the foregrounding of musical hybridity is the recent increase in interaction among different Latino communities in the United States (the adjective inter-Latino is used to describe this type of interaction). Latin American immigrants to the United States not only encounter the dominant Anglo culture but also other Latin American cultures, often for the first time. The marked diversification of the Latino population since the 1990s has resulted in a noticeable growth in the number of inter-Latino marriages and other cross-cultural affiliations. An increasing number of young Latinos today thus experience an added layer of hybridity, since they may embody two or more national groups (e.g., MexiRican, CuBolivian). Inter-Latino diversity is challenging the long-standing approach to thinking about Latinos in terms of a single external national affiliation (such as “Cuban American”). Inter-Latino interaction in the United States has become an important trend in popular music, as exemplified by the international hits of Shakira and Wyclef Jean’s “Hips Don’t Lie” (Colombian and Haitian) and Café Tacvba and producer Gustavo Santaolalla’s “Eres” (Mexican and Argentinean, discussed in Chapter 3); and it is particularly key in urban music’s “featuring” phenomenon, as exemplified by “Un Día” by J Balvin, Dua Lipa, Bad Bunny and Tainy (Colombian, British-Albanian, and two Puerto Ricans).

There is much to laud in such music. A hybrid aesthetic rejects notions of racial and cultural purity and instead celebrates the multiple associations and influences in our lives, regardless of our ethnicity. For Latinos in particular, hybridity is a feature of Latinidad, the shared culture and experience of Latin American immigrants and their descendants in the United States. Thus, hybrid music (“neither here nor there” or “both here and there”) can speak powerfully to the life experiences of Latinos and other immigrant communities.

Although the notion of hybridity may suggest egalitarian cultural exchanges, one needs to be aware of the power dynamics that often surround them. In hybrid expressions, one culture almost always dominates. For example, in Nor-tec music (the hybrid style of techno and Mexican banda discussed in the book’s introduction), DJs sample banda music to create electronic music pieces, not the other way around. (Although the idea of a brass band emulating the blips and beats of techno is intriguing, most likely, the resulting music would not be considered banda by banda fans and might not be appealing to them.) Moreover, hybridity can easily contribute to ethnic ambiguity, creating a common-denominator product to maximize potential consumer audiences. From a marketing perspective, the more styles included in an album, or even within a single song, the larger the number of communities that may purchase it. However, in creating ethnic ambiguity, hybridity can function as a homogenizing force that conceals or downplays socio-cultural differences

This chapter provides a sample of important trends in popular Latin/o American music of the twenty-first century. It emphasizes artists who have one foot in Latin America and one in the United States, who have a sizeable following across the Americas, who win Grammy and Latin Grammy awards, and whose music is widely available for purchase. Although contemporary popular musics created by Latin Americans and U.S. Latinos have many things in common (and often sound very similar), it is important to recognize that U.S. Latinos are a distinct group from Latin Americans. U.S. Latinos constitute an ethnic minority >with a long history of struggle for civil rights and social recognition. As such, the music of U.S. Latinos holds a different set of meanings as the expression of a historically disenfranchised minority. For that reason, this chapter is divided into two sections. The first section covers contemporary Latin American popular music (with examples by Colombian, Mexican, and Puerto Rican artists), and the second examines recent trends in popular music by U.S.-born Latinos.

During the first two decades of the new millennium, some of the most commercially successful Latin American artists have been from Colombia. In the 2000s, Shakira and Juanes were particularly successful, and they had a lot in common. Both are Colombian singer-songwriters who grew up in cosmopolitan environments that exposed them to a wide range of music, with British and U.S. rock at the core. Both relocated to the United States in the late 1990s to reinvent and internationalize their careers. Both use a hybrid approach to commercial pop-rock; that is, they borrow from a wide range of local and international styles to “spice up” their radio-friendly hits. After 2010, a younger generation of Colombians has taken center stage. Karol G and J Balvin are both reggaetón artists from Medellín, Colombia, who had long careers in their home country before their international breakthroughs. Both are part of the development of a Colombian reggaetón style, known for emphasizing singing and for lyrics that are less explicit than the ones common in other traditions.

In the United States, these musicians are some of the most visible faces of “new Latinos.” The marked increase in migrant populations from South and Central America since the 1990s has challenged the perception of U.S. Latinos as primarily Mexican, Puerto Rican, or Cuban––the three historically dominant Latino communities––and has shifted attention away from stateside Latino culture to Latin American culture. The two songs discussed in this section are among the most popular Latin/o American hits of the twenty-first century’s first decade. Shakira’s 2005 “La tortura” (Torture) spent 25 weeks at the number one spot on the U.S. Billboard Latin Pop chart. Juanes’s 2007 “Me enamora” (She Seduces Me) follows right behind it, having stayed at number one for 20 weeks. Shakira’s piece won Latin Grammy awards for best song and record of the year, and so did Juanes’s two years later.

Shakira (Shakira Isabel Mebarak Ripoll, b. 1977) is the most successful Latin American singer worldwide in recent years. She is a global phenomenon and has recorded songs in Spanish, English, and Portuguese. Shakira has been described as “pop’s twenty-first-century Latina bombshell,” a moniker that echoes how Brazilian Carmen Miranda was characterized in the late 1930s (see Chapter 6). Yet she is also known for her intellectual curiosity; in an interview, she once explained the choice of covers for her albums with references to Freud’s psychoanalysis and Jungian archetypes.

Shakira is a fascinating example of a global Latin American who resists easy categorization. Born in Barranquilla, an important port town on Colombia’s northern Caribbean coast, she is of Lebanese and Spanish ancestry and describes herself as a mix of “raw kibbeh and fried plantain.” She grew up in a cosmopolitan environment, and her early musical preferences were divided between Anglo bands like Nirvana, Led Zeppelin, The Cure, and songs derived from her Arabic heritage.

Shakira’s international popularity began with her third album, Pies descalzos (Bare Feet, 1996), which she cowrote and coproduced with Luis Fernando Ochoa. Already in this early album, one can hear Shakira’s eclectic approach to popular music. The song “Un poco de amor” (A Little Bit of Love) featured a Jamaican dancehall beat and guest vocals by reggae singer Howard Glasford. Two years later, she released what many critics and fans consider her best album, Dónde están los ladrones? (Where Are the Thieves?), a considerably more ambitious CD featuring mariachi trumpets (“Ciega, sordomuda,” Blind, Deaf, and Dumb), bolero-style percussion on the bongos (“Moscas en la casa,” Flies in the Home), and the Middle-Eastern oud, a fret-less pear-shaped precursor of the guitar (“Ojos así,” Eyes Like That).

Interested in expanding her popularity to include the U.S. market, Shakira did what many Latin American artists have done since the early 1980s: move to Miami. Riding the wave of the late 1990s “Latin Explosion” (In Depth 10.1), she released her first English- language album, Laundry Service, in 2001. The album topped charts around the world, yet many Latin American critics felt that Shakira had sold out and overly “Americanized” her sound. They pointed out the changes in lyrical themes on the release (mostly about love, whereas she had sung about political or socially engaged issues previously) and in her image. Shakira had dyed her dark hair blonde, along with other image changes in dialogue with American pop stars. All of this elicited rather unfavorable comparisons to Britney Spears.

On her follow-up album, Shakira took a different strategy. Instead of producing a one-size-fits-all crossover release, she divided her audience and provided two distinct products, one in Spanish (Fijación oral, Vol. 1, 2005) and months later one in English (Oral Fixation, Vol. 2, 2005). Although the album titles suggest that one release is a translation of the other, only two songs appear on both albums. Shakira explained that the musical elements used in a song naturally lead her to the language she should use to record it. You can hear this: the album intended for an Anglo audience is more homogenous, incorporating mostly rock influences. The Spanish-language one, by contrast, is strikingly eclectic. A New York Times review labeled it “blissfully pan-American”; an even better descriptor might be “worldly,” given that many of its influences come from beyond the Americas. Tracks include nods to Brazilian bossa nova, 1960s French pop, 1980s British synth-pop, reggaetón, and Argentine rock nacional. In Fijación oral, Vol. 1, she comes across as an informed listener with a profound knowledge of popular music from many countries, and the album proved an important point to her Latin American critics: that she had not replaced her Colombian/Latin American identity with a U.S. one. Instead, she absorbed what the United States and Europe had to offer and used it creatively in conjunction with her Latin American heritage.

The first single of Fijación oral, Vol. 1, “La tortura” (Torture, Listening Guide 10.1), is a duet with Spanish balladeer Alejandro Sanz, a major pop star in Spain and in Latin America. Structured as a conversation, the song tells us that Sanz cheated on Shakira and is now apologizing, but only half-heartedly. The true feelings of each singer are ambiguous until the second half of the song, in which Sanz acknowledges he wants forgiveness but plans to continue misbehaving (on Saturdays!). The story’s twist comes at the end when Shakira recognizes that he will not change and then breaks off their relationship. Musically, the song is a catchy mix of reggaetón, Colombian vallenato accordion playing, and Jamaican dancehall, together with the flamenco-stylized vocals of Sanz.

The music video for “La tortura,” directed by the renowned Michael Haussman, broke MTV’s unspoken language barrier when it aired on the station without translation or subtitles. The video is largely about the male singer’s voyeuristic gaze, as he peeks at Shakira from an adjacent apartment window. Using a fragmented narrative, Haussman undermines the possibility of understanding the song in a monolithic way. There are times in the video when we are likely to empathize with Sanz, a few seconds later to despise him. Most interestingly, as Sanz watches Shakira lsciviously, we—the viewers—become voyeurs as well, complicit in his transgression.

Shakira’s savvy use of images recalls an artist like Madonna, an early star of the music-video era. Like Madonna in the 1980s, Shakira plays with various female stereotypes, for instance, the naïve virgin when she sings in a childish voice (“Día de enero,” January 10 Formatted: Position: Horizontal: Right, Relative to: Margin, Vertical: 0″, Relative to: Paragraph, Wrap Around Day), the sexually charged bombshell (“Las de la intuición,” Women with Intuition), or the nurturing mother (on the CD’s cover art; Figure 10.2). Also, like Madonna, Shakira uses her body and dancing to garner attention, and once we look at her, she makes us aware of the very act of looking.

In depth

At the dawn of the twenty-first century, Latin American and U.S. Latino popular music seemed unstoppable. Ricky Martin’s electrifying performance in the 1999 Grammy Awards ceremony landed him a Time magazine cover and countless media appearances. Martin’s achievement paved the way for a cadre of Latin/o American artists who found commercial success in the United States and beyond with English-language pop albums. The artists of the so-called “Latin explosion,” who, besides Martin included Marc Anthony, Jennifer Lopez, Enrique Iglesias, and Shakira, followed the model of 1980s crossover stars Gloria Estefan and the Miami Sound Machine. This is not coincidental; Miami Sound Machine founder and Gloria’s husband Emilio Estefan Jr. produced several of the “Latin explosion” albums. The tenants of Estefan’s crossover model include the use of standard American verse–chorus song format; the incorporation of subdued Latin American music influences, such as the syncopated keyboard of salsa (derived from the salsa montuno; see Chapter 5), nylon-string guitar runs, and —most importantly—lyrics in English, peppered with a few easy-to-pronounce Spanish words. The financial appeal for Latin/o Americans of reaching the U.S. Anglo music market is undeniable. The United States is the largest market for recorded music in the world, accounting for 27 percent of global revenues in 2008. By comparison, the largest Latin American market for music is Bazil (which represents 1.2 percent of global revenues), followed by Mexico (0.8 percent) and Argentina (0.3 percent). The urge to record in English was especially strong in the first decade of 2000 because the English-speaking United States has a long history of resistance to popular music in other languages. In 2007, for example, the Spanish-language album market represented only a modest 5 percent of total sales. However, this situation has changed over time. In 2017, the global phenomenon of the song “Despacito” by the pop Puerto Rican singer Luis Fonsi featuring the reggaetón artist Daddy Yankee showed that Latin American music in Spanish could appeal to English language audiences. In the years since, artists like Bad Bunny, Karol G, Feid, and Rauw Alejandro have done arena tours of the US with a repertoire sung exclusively in Spanish. And in 2023, Karol G debuted at number 1 on the Billboard 200 albums chart with Mañana Será Bonito, the first Spanish-language album by a woman to achieve this.

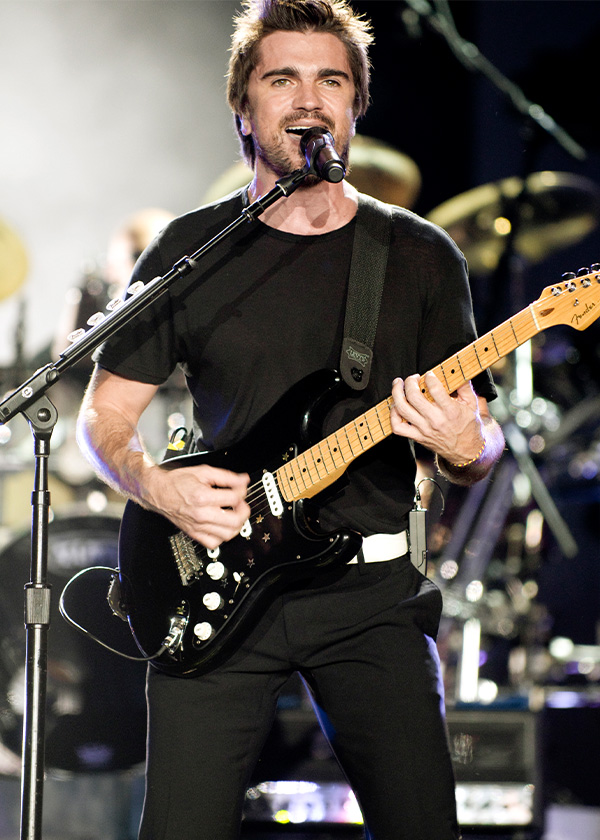

Singer-songwriter and guitarist Juanes (Juan Esteban Aristizábal Vásquez, b. 1972) started his career in his home country of Colombia as lead singer for a heavy metal band. In 1998 he moved to Los Angeles to start a solo career, and the half-dozen albums he has released since have topped the charts throughout Latin America, the United States, and Europe. To date, he has more Grammy awards than any other Latin American or U.S. Latino artists. Perhaps the most striking feature of Juanes’s international success is the fact that he has achieved it singing in Spanish. When prodded as to why he does not sing in English he responds: “I prefer to play guitar in English and sing in Spanish.”

In his music and appearance, Juanes combines three important types of Latin American musician. He is part urban, scroungy rocker who can solo on the electric guitar; part romantic crooner with a smooth voice; and part socially conscious singer-songwriter. Although he borrows from all these styles, his sound is considerably more homogenous than Shakira’s. His songs are arranged for a traditional rock combo of electric guitar, electric bass, keyboards, and drum set—and he regularly performs his songs live with a small band. Gustavo Santaolalla, an Argentine composer and producer who lives in Los Angeles, has been behind Juanes’s entire solo career. Not only has Santaolalla produced or coproduced all of Juanes’s records, but he is responsible for encouraging Juanes to incorporate elements of Colombian traditional music into his pop-rock mix, adding yet another layer to his hybrid style.

Juanes manages to be a pop star and still sing about social issues. A recurring theme in several of his songs is the problem of landmines in Colombia, an ever-present threat. Since 1990, landmines have led to more than eight thousand amputees there, and some estimates suggest that they claim three victims a day. Juanes has also taken an active role in organizing concerts with a sociopolitical agenda. He organized a Peace Without Borders concert in response to the diplomatic crisis that affected Ecuador, Colombia, and Venezuela in 2008. A year later he organized a controversial second Peace Without Borders concert in Havana, Cuba. Given Juanes’s massive following, these activities have resulted in public acknowledgments by the presidents of Venezuela, Colombia, Cuba, and the United States.

Juanes’s international hit “Me enamora” (2007, Listening Guide 10.2) is one of his best-known songs. An upbeat love song with a lilting guitar intro, a strong downbeat, and a memorable chorus, “Me enamora” topped the charts in over a dozen countries and won two Latin Grammy awards. The electric guitar solo borrows from classic Anglo blues rock, illustrating well what Juanes means by an “English-speaking” guitar.

Although there are many important similarities between the music of Shakira and Juanes, some key differences should be noted. Perhaps the most controversial is their choice of language. As part of her crossover effort, Shakira learned English and began to write and record in English alongside Spanish. Juanes, on the other hand, has continued to sing in Spanish. Language is just one of many aspects in which Shakira is open to experimentation. Her singing is notably versatile. She can sound soothing and comforting at one point, intense and angry on the following track, only to be close to sobbing on the next. And in her music she has embraced a plethora of international styles. Comparatively, Juanes’s style has changed considerably less during the past decade. His lyrics have evolved with each album, but musically he has remained close to the sound he and Gustavo Santaolalla developed for his first solo album in 2000, a compelling mix of classic rock with Colombian traditional music elements.

Shakira and Juanes demonstrate that Latin American artists can achieve worldwide success in the commercial music market, and in different ways. Their urbane and cosmopolitan music represents their status as global citizens. It is of utmost importance to recognize that for cosmopolitan musicians like Juanes and Shakira, hybridity is a choice, the result of individual aesthetic decisions as well as of education and privileged social position. For many others, like the poor Mexican migrant workers discussed in the next section, hybridity is an imposed reality, the result of fragmented lives and the need to fit in a host society.

The Mexico–U.S. border is a musically rich region that spans almost two thousand miles and represents home for more than ten million people. The border region can be described as a contact zone, a place where cultures meet, and identities are challenged by the encounter. Unlike the experience in the heartland, border inhabitants are constantly reminded of their national identity through contrasts with others. Yet for many who live by the border, patria or homeland is truly the border itself, not Mexico or the United States. Chicana author Gloria Anzaldúa has famously described the U.S.–Mexico border as “two worlds merging to form a third country.”

Northern Mexico has a distinct identity, historically estranged from that of the capital, Mexico City, and comparable to the relationship between those in Texas or the southwest United States and Washington, D.C. Mexican northerners have a self-sufficient mindset, developed from decades building communities in harsh terrains without enough aid from the central government. Understandably, given the region’s proximity to the United States, the far North is Mexico’s most “Americanized” region––a sore point for the Mexican government. From Mexico City, the northern frontier appears as a porous zone where Mexicanness is diluted and U.S. culture is all too prevalent. Government officials do not always recognize the rich culture that exists at the border, reflected in the various music traditions that have blossomed there. Border culture is particularly diverse in terms of well-established popular music traditions, everything from working-class, largely unrecorded rural styles like huapango (see Chapter 3) to the mass-mediated tejano style of the late Selena Quintanilla.

Throughout the twentieth century, a common theme in border music was the border experience itself. Songs celebrated self-reliance and discussed legal and illegal border crossing, the difficulties of working far from home, and staying true to oneself amid the constant push and pull from north and south. As a result of changes in migration patterns, in recent decades, the themes of border music have undergone important transformations. This section’s examples represent three cases of twenty-first-century border music: music of working-class northern Mexicans, undocumented migrants, and a new generation of cosmopolitan performers.

Mexican laborers have been crossing over to work in U.S. territory since the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848. In the mid-twentieth century, the Immigration and Naturalization Service’s Bracero Program streamlined the process by which Mexicans could enter the United States to work temporarily in agriculture and railroad building. Bracero is a Mexican Spanish term for temporary laborer (from the Spanish word for arm).

By the time the controversial Bracero Program was terminated in 1964, the use of Mexican labor had been institutionalized. Farms and factories still relied on cheap Mexican labor, and the vast numbers of Mexican nationals in need of work resulted in an exponential growth in nonofficial immigration. In 2019, there were about eleven million Mexican immigrants (foreign-born) in the United States, of which about half were undocumented.

Changes in immigration laws and border control during the last twenty years have resulted in new migration patterns that have transformed the lives of undocumented migrant workers. Border control has tightened; thus, migrants are crossing less often and opting instead for longer stays in the United States. While historically, the vast majority of migrants had been working-age men, in the last two decades, an increasing number of women and children have joined them. In the past, Mexican migrants had remained close to the border, primarily in California and the Southwest. Today, they find work all across the United States; thus, some of the fastest-growing Mexican communities are now in the Pacific Northwest and in the Northeast, as well as in the Carolinas and the Southeast.

Another important shift is that recent migrant workers are considerably less invested in assimilation into the United States, as demonstrated, for example, through a lack of interest in learning English or in becoming a U.S. citizen. This can be partly explained by the hostility they encounter: in the new millennium, the United States has become a considerably less welcoming place for immigrants than it used to be. Also, recent developments in technology and travel have allowed immigrants to maintain long-distance communication with their families and places of origin. In a sense, these newly arrived peoples remain closer to their hometowns than ever before.

The most concrete way in which migrants remain connected to their hometowns is by sending back part of their earnings to family. These monies, called remittances, have grown so much in recent years that they have become a key component of several Latin American countries’ economies. For example, in 2023, remittances sent from the United States to Mexico reached $63 billion dollars. The Mexican government, aware that migrants who remain connected with their hometowns are more likely to contribute to their local economies, has developed policies that aim to maintain such links. For example, since 2005, Mexicans abroad have been able to vote in local elections in their former places of residence.

Migrant workers have been quick to adopt new technologies for music consumption. Their inherent mobility and the need to maintain regular communication with people back home have made smartphones and online interaction an essential part of their lives. Not only is the cell phone their primary means of communication, but it is also their main means of acquiring music. In 2008, Latinos were twice as likely to buy ringtones as were non-Latinos.

Before the advent of the reggaetón craze, Regional Mexican–an umbrella category that includes música norteña, ranchera, and banda–was the dominant style of Spanish-language music in the United States. In 2008, it accounted for 62 percent of all U.S. Latin music sales, and in 2023, the song “Ella baila sola” by Eslabón Armado and Peso Pluma reached one thousand million streams on Spotify, making it the first Regional Mexican to reach the Billboard Hot 100 Top 10. Given the strong ties between Regional Mexican and cell phone use, phone carriers have built more partnerships with regional Mexican artists than with any other genre, Latin or not.

The most popular music among Mexican migrant workers, particularly undocumented ones, is música norteña (see p. 107). The standard instrumentation of a norteña ensemble features a three-row button accordion, bajo sexto, electric bass, and drums. Set to dance-oriented styles like polka and waltz, música norteña incorporates many pieces with socially conscious lyrics that might be described as contemporary corridos, traditional Mexican narrative ballads (for more on corridos, see Chapter 3). In norteña, the emphasis is on lyrics rather than instrumental virtuosity; in fact, only minimal accordion soloing is used. (If you enjoy virtuosic accordion playing, check out Texas–Mexican conjunto, the north-of-the-border version of norteña that focuses on instrumental dancehall numbers and features striking accordion solos.) Norteña’s lyrics deal with the experience of migration and celebrate Mexican traditions as well as resistance to assimilation. Norteña songs contribute to the development of a sense of community at a time and place when identities are most frail and in flux. As Cathy Ragland puts it, norteña creates “a nation between nations.”

The main audience for música norteña is in Northern Mexico (Tamaulipas and Nuevo León) and among Mexican migrant laborers in the United States. But in recent years, norteña’s popularity has extended as far south as Mexico City. With one out of ten Mexicans living in the United States, norteña’s stories of displacement are striking a chord even with the ones who stay behind. The most famous norteña acts are Ramón Ayala y Los Bravos del Norte, Los Tucanes del Norte, and Los Tigres del Norte.

Los Tigres del Norte have made a five-decade career of singing about border crossing and immigrant life. In 1968, while still teenagers, the four brothers Hernández from Sinaloa entered the United States hoping to make money playing music. They eventually settled in San José, California, began recording with Fama Records, and went on to sell more than forty million albums. Los Tigres specialize in the performance of corridos that deal with contemporary social issues. They are largely responsible for modernizing the corrido by replacing the genre’s traditional poetic speech with a plain, working-class language.

In the early 1970s, Los Tigres del Norte found fame recording narcocorridos, a subgenre of corrido that chronicles the lifestyle and tragic adventures of border-crossing drug smugglers (p. 93). Though still known for their popular narcocorridos, since 2000 Los Tigres del Norte have moved beyond the style to sing more broadly about the life of the mojado or wetback, the poor immigrant that crosses the border illegally. They have also added songs that address sociopolitical issues in Mexico itself (listen to “La granja,” The Farm, from 2009, an allegory of political corruption which was censored by concert promoters in Mexico). The recent immigration trends outlined above are reflected in Los Tigres’s recent de-emphasizing of border crossing itself and newfound interest in the struggles of migrants within the United States, particularly assimilation.

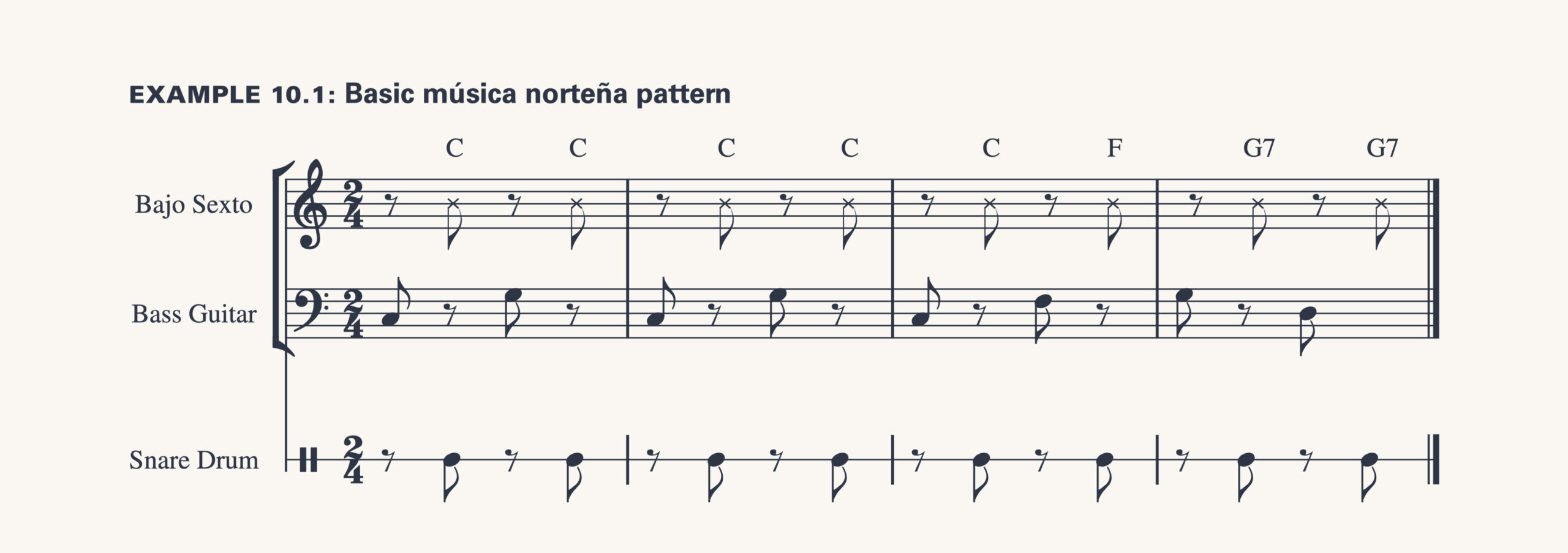

One representative example of Los Tigres’s recent work is “De paisano a paisano” (From Countryman to Countryman, 2000, Listening Guide 10.3). Like most Tigres songs, “De paisano a paisano” is in duple meter, and the arrangement and production are straightforward. At its core lies a regular pattern of a bass guitar note on the downbeat followed by a chord on the bajo sexto played together with the snare drum (Example 10.1). This is the typical manner of interpreting polka music in norteña repertoire. The accordion plays the introductory melody and the fills between verses; accordion lines are simple and memorable, rather than showy and virtuosic. Vocal harmonies are used only during the chorus.

Although Los Tigres’s concerts attract both men and women, their songs bear traces of a tradition of performance that occurred in male-only spaces, such as local cantinas. Thus, song lyrics often describe conversations among men. Even in songs about love or heartbreak, the lyrics do not address a woman directly, but rather a buddy or a relative. As the title suggests, “De paisano a paisano” (From Countryman to Countryman) recounts a story told from man to man. It celebrates the untamable character of the mojado, who could be from anywhere in Latin America, bravely crossing borders to provide for his children, and his anti-assimilationist attitude. The song presents the mojado as a heroic outlaw.

“De paisano” illustrates Los Tigres del Norte’s uncanny ability to embrace commercialism while maintaining a populist, even oppositional stance vis-à-vis the mainstream. On the one hand, the song appeared in TV ads in which the band promoted a money-transferring company. On the other, Los Tigres used the same song to record a different ad promoting a campaign of Mexico’s Secretaría de Gobierno; the campaign aimed to inform Mexican workers abroad of their rights and privileges and was appropriately named the “Paisano program.” Los Tigres’s popularity has extended the appeal of corrido beyond its original border audience to include people in Mexico City and in places as far off as Chile and Spain. The group has even shared the stage with mainstream Latin pop artists like Ricky Martin and the Mexican ska/pop/rock group Maná. For millions of undocumented workers (throughout Latin America), Los Tigres del Norte tell an inspiring story of a mojado’s triumph against all odds.

Nothing represents border culture better than the Mexican city of Tijuana. Tijuana is the busiest port of entry in the U.S.–Mexico border, stamping over forty million crossings a year. For most of the twentieth century, Tijuana had a bad reputation in both countries. In the United States it was conceived as a city of sin and debauchery; and in Mexico, Alejandro L. Madrid writes, as “the barbaric land where U.S. cultural imperialism threatens Mexican, Latin American, and Hispanic culture in every bar where you order your beer in Spanglish and pay with a mix of dollars and pesos.” Tijuana appears from both these perspectives as a place where a large transient population prevents the emergence of a lasting social or cultural identity, a town neither here nor there.

In the new millennium, however, Tijuana-based artists have been challenging stereotypes of the border region. Authors, visual artists, musicians, and dancers argue that their culture has been misunderstood and that foreign critics miss the point by expecting a static Mexican identity from Tijuana. Instead, they posit, Tijuana needs to be understood as a multicultural place, and scholars agree. Researchers argue that tijuanenses have a strong national identity, fueled in no small measure by the experience of constant contact/friction with the United States. What is unique about tijuanenses, Jennifer Insley suggests, is that they “incorporate signs and symbols from elsewhere without perceiving a contradiction between these and a fluid but strong sense of national, ethnic, and linguistic selfhood.”

The Tijuana multimedia art form known as Nortec, discussed briefly in the Introduction, is a perfect aural representation of contemporary Tijuana culture. Nor-tec stands for a hybrid of norteña and techno, the local and the global. Musically, this means that Nor-tec DJs take samples from classic norteña and banda sinaloense (see Chapter 3) tracks and fuse them with the beats and loops of electronic popular music. Rather than an amorphous “neither here nor there” style, Nor-tec is better thought of as both here and there.

Singer-songwriter Julieta Venegas (b. 1970) represents yet another kind of border pop musician, similar in some respects to Shakira and Juanes. Born in Long Beach, California, to Mexican parents, she spent her formative years in Tijuana. Like many young tijuanenses, Venegas had more contact with San Diego, California, than with the far-away Mexican capital. Venegas and her music can be best described as cosmopolitan. On the one hand, she is strongly rooted in Mexican culture: despite being fluent in English she has shown no interest in writing songs in that language, nor in moving to the United States. On the other hand, she grew up listening to Anglo rock and borrows freely from it. The international quality of her music makes it equally appealing and meaningful to Argentineans as to Spaniards and North American critics, who have celebrated her music since the release of her first album, Aquí (Here) in 1997.

While Venegas’s first instrument is the piano, she is most widely recognized for playing the keyboard accordion. Interestingly, Venegas picked up the accordion after being inspired not by música norteña repertoire but by alternative rock musicians Tom Waits’s and Joe Jackson’s use of the instrument. Her 2008 Unplugged album for MTV illustrates Venegas’s keen musicality. The most common pitfall of acoustic pop-rock albums is their aural monotony; stripped of guitar pedals and other sound effects, there is often little except the melody to distinguish one song from the next. Aware of this, Venegas worked with Brazilian Jaques Morelenbaum, long-time collaborator of bossa nova founder Antônio Carlos Jobim, to re-create her songs for live concert settings. Relying on several multi-instrumentalists, the elegant yet lively arrangements present an eclectic kaleidoscope of sounds, from a classical string quartet to tuba, from cavaquinho (see Chapter 6) to a saw blade played with a bow.

“El presente” (The Present, Listening Guide 10.4), the first single off the album, showcases Venegas’s cosmopolitan aesthetics. The song opens with Venegas playing a lilting line on the accordion over a lively polka rhythm and bass pattern. In the chorus, the percussion drops off and is replaced by sustained string notes and Beatlesque vocal harmonies, producing an out-of-time feel. Venegas current career is still aligned with this spirit, having collaborations with the Puerto Ricans Bad Bunny and Tainy in the song “Lo siento BB” among others

The corrido, the enduring narrative ballad connected to Spanish romance and the Mexican Revolution, has been widely transformed in recent years (see Chapter 3). Directly related to the narcocorrido from Los Tigres del Norte, corridos tumbados show the influence of urban music on Mexican and Chicanx youth as well as ties to regional Mexican traditions. The term tumbado, slang for hostile and cool, has been used since the development of hip-hop culture in Mexico to name a new generation of narrative songs that incorporate some aesthetic elements of Latin trap and reggaetón. This intersection has fostered new associated subgenres, such as corridos bélicos and dembow bélico.

Corridos tumbados maintain the musical and lyrical characteristics of corrido and its variations: strophic form with four-line stanzas, each with eight syllables overall; storytelling lyrics; memorable melodies; and an acoustic instrumentation with guitars, bass, wind, and brass. They also present new elements, like rapping, and a less lyrical delivery. The biggest change, however, has been in terms of collaborations and visual aesthetics. Corrido musicians have joined the urban music trend related to featuring, especially with well-known reggaetón artists like Arcángel and Wisin & Yandel. Musical videos, live performances, and clothing have been the arena of aesthetic exploration; corrido musicians maintain traditional Mexican references with mixed outfits, incorporating jewelry and urban clothing historically associated with hip-hop and reggaetón culture.

Single artists like Peso Puma, Natanael Cano, Junior H, and tumbado bands like Fuerza Regida, Eslabón Armado, and Yahritza y Su Esencia illustrate youth’s strong connection with contemporary life, social struggles, and the realities of border-crossing. Along with maintaining a musical tradition, professional musical craft, and exploring urban aesthetics, these musicians address topics like migration, family, love, and crime. Like narcocorridos before, corridos tumbados have been the source of controversies and even attempts at censorship. Some have denounced the lyrics for their machismo and misogyny, while others have argued that they celebrate illicit activities and crime.

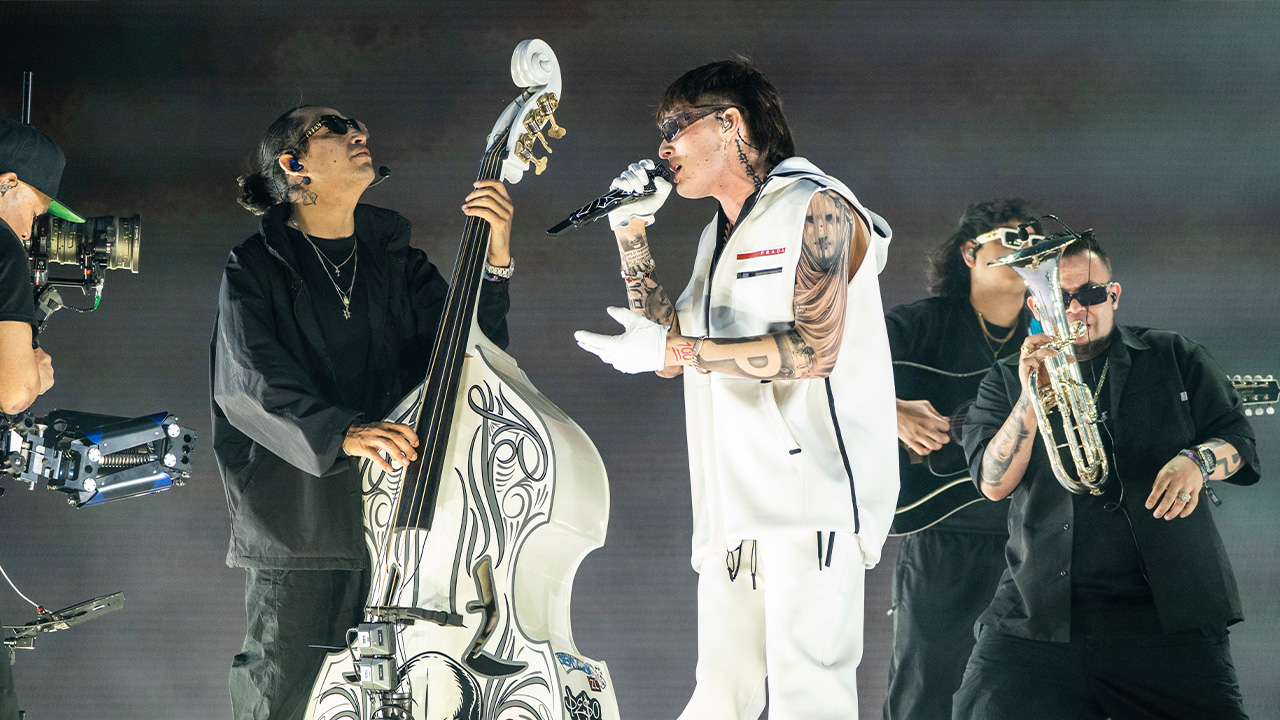

“Igualito A Mi Apá” (Listening Guide 10.5) is a song by the Mexican American band Fuerza Régida and the Mexican singer Peso Pluma (Hassan Emilio Kabande Laija, b. 1999). With a sierreño music instrumentation—requinto (twelve-string guitar), percussive guitar, tuba, and tololoche (Mexican contrabass)—Fuerza Regida and Peso Pluma engage in a narrative with two layers of meaning: family and crime. On one level, the song speaks of the patriarchal heritage between a father and a son, passing down habits and tastes. At a second level, however, references to guns and drug culture have made listeners hear this song as one about drug dealer Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzman and his son.

As we saw in the previous section, remittances by Latin Americans working in the United States are so large that Latin American economies have begun to depend on them. Latino-studies scholar Juan Flores suggests that migrants’ influence in their home countries extends far beyond monetary contributions. Flores proposes that migrants also transmit what he calls “cultural remittances,” by which he means ideas and expressive forms, like music, that arrive in Latin America when migrants return home to visit or to relocate. In addition to physical visits, recent technological developments in communications have made the transmission of expressive forms from the diaspora to the homeland considerably easier than in previous decades.

One of the musical styles that arrived in Latin America as a cultural remittance is hip-hop. Spanish-language rap first became popular internationally in the 1990s. It did not take root in a single location; instead, all across the Americas MCs and DJs tried their hand at this exciting style that originated in New York City. Some of the most important 1990s Latin American rappers include Panamanian El General, Puerto Rican Vico C, the Chilean Ana Tijoux, and bands Illya Kuryaki and the Valderramas from Argentina, and Control Machete and Molotov from Mexico. The most important international break for rap influence in Latin America came in the new millennium with the worldwide success of reggaetón (see Chapter 5) and trap Latino. Alongside transformations and new genres, these types of music have been understood as part of an urban music movement, a well-spread and accepted concept among practitioners.

In the United States, Latinos have been involved in hip-hop culture–– DJing, graffiti, breakdancing––since its early days in the South Bronx in the late 1970s. By the late 1980s, a few Latino artists had crossover success rapping in English, sometimes peppering the lyrics with Spanish phrases and slang. Examples include Cuban-American Mellow Man Ace (“Mentirosa,” 1989), Chicano Kid Frost (“La Raza,” 1990), and Ecuadorian- American Gerardo (“Rico Suave,” 1991). More recently, the Dominican-York Cardi B and the Puerto Rican Young Miko have released chart-topping albums in the United States.

Throughout Latin America, there is also an important, albeit less commercially successful form of hip-hop that raps about sociopolitical issues. Political rap, known as “hip-hop social” in Colombia and as “rap consciente” in Cuba, has been particularly important among Afro-Latin American youth. Inspired by African American rappers who use hip-hop to celebrate a shared African diasporic experience, Latin Americans rappers adopt the style to decry social and racial inequality and challenge the status quo. This grassroots rap can be considered the torchbearer of 1970s political song (see Chapters 4, 5, and 7). Since 2000, one hip-hop group that has managed to create catchy party tracks and politically engaged rhymes en español is the Puerto Rican band Calle 13 (Figure 10.7). Calle 13 consists of rapper and frontman René Pérez (aka Residente), multi-instrumentalist and producer Eduardo Cabra (aka Visitante), and vocalist Ileana Cabra (aka iLe). They first achieved international popularity in 2006 as reggaetón artists with the song “Atrévete-te-te.”

Calle 13’s third album, Los de atrás vienen conmigo (Those in the Back Are Coming with Me, 2008), is to date their most ambitious both musically and lyrically. Its eclectic musical mix (the New York Times described it as “omnivorous”) includes influences from polka, Balkan brass bands, 1980s synth pop, and Nigerian Afro-beat. Lyrically, Los de atrás is an aggressive, albeit humorous, album: rapper Residente takes on, among other things, reggaetón’s frequent glorification of consumption and excess and its misogyny; dancehall singer Sean Paul’s accented English; and Latin American social climbers who pretend to be American and reject their heritage wholesale (“gringa wannabe”). But there is an important exception to such biting commentary: the third single, “La Perla” (Listening Guide 10.6) is a heartfelt, nostalgic ode to the San Juan working-class neighborhood of the same name.

Like many Calle 13 songs, “La Perla” disparages the bling lifestyle, celebrating instead the simple pleasures of family life in the barrio: brightly painted houses, boys jumping across rooftops, an adolescent’s first kiss, grilled food, cold beer, and shooting hoops with friends. In evocative and highly visual vignettes, Residente raps that he’s not interested in modernization but in staying true to his heritage, represented by the image of his mom’s food and his grandmother in a rocking chair. The chorus boasts of barrio pride: “I have everything/I don’t lack anything/I have the night, which is my blanket/I have the best skyscapes/I have a cooler stacked with iced beer.” The musical arrangement by Visitante is sparse to keep the listener’s attention on the lyrical flow. It features an Afro-Uruguayan style called candombe (see Chapter 7), played by the Argentine percussion group La Chilinga (notice how candombe shares the 3-2 clave pattern of Afro-Caribbean music).

The second half of “La Perla” includes a rap and a soneo (an improvised vocal in call-and-response form) by renowned Panamanian salsa singer-songwriter Rubén Blades, known for his socially conscious songs. Blades continues Residente’s celebration of barrio life and its matrilineal culture but suggests that La Perla is a “barrio universal” representing working-class life across the Americas. His collaboration with the hipsters in Calle 13 introduced Blades to a younger generation, while his socially conscious rap lent credibility to Calle 13’s political leanings. The music video, a beautiful realization of the song’s narrative, won a Latin Grammy for best video.

Tracing the origins of reggaetón is complicated. This transnational music and dance genre is the result of migration and cultural exchange across Jamaica, Panama, Puerto Rico, and the US. As some scholars suggest, reggaetón exemplifies the multiplicity of overlapping music and dance circuits that do not necessarily comply with geographic, national, or language boundaries. As Chapter 5 explores, there is not a single event that we can point to as the launch moment of this tradition, although reggaetón started in a cross-fertilization process that encompassed Jamaican dancehall and sound system culture, Panamanian reggae in Spanish, Puertorrican reggae and bomba, and American hip hop, traceable back to the 1970s and 1980s.

During the 1990s, several musicians, like the Puertorricans Vico C, Tego Calderón, DJ Blass, DJ Playero, and the young Daddy Yankee, along with the Panamanians El Chombo, Renato and Franquito, started to explore a new type of hybrid music, simultaneously called reggae in Spanish, melaza, música negra, or underground. In places like Puerto Rico, early reggaetón was persecuted as part of a racist and classist backlash, framed within a policy instated by Governor Pedro Roselló in 1993 (see case of “Loiza” in Chapter 5). Known as Mano Dura Contra el Crimen (Iron Fist Against Crime), this unsuccessful approach focused on crime prosecution without engaging the island’s profound inequalities. As a musical response of sorts, the work of rappers Vico C and Tego Calderón was highly influenced by these social matters.

At the end of the 1990s, this music-dance genre expanded throughout the Americas, boosted by the work of some radio stations, album piracy, and online interchange. Today, contemporary reggaetón has reached the anglophone and Hispanic world beyond Latinx communities. Across Latin America, local variants of reggaetón have developed, like the romantic and lyrical singing of Karol G and Feid in Colombia, the turreo or RKT of La Joaqui and L-Gante in Argentina, and the flaiteo of Cris MJ and Pablo Chill-e in Chile.

Bad Bunny (Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, b. 1994) is today a world-wide phenomenon. His stellar career started in his native Puerto Rico, posting songs to SoundCloud in 2016, a platform that helped him to achieve online recognition and get a contract with the independent label Rimas Entertainment. His continental debut arrived the same year with the trap song “Diles” (“Tell Them”) alongside the established reggaetón artists Arcángel, Ñengo Flow, Farruko, and the young Ozuna. During this time, he achieved high numbers on streaming platforms with songs like “Soy Peor” (I am Worst) and “Tu No Vive Así” (You Don’t Live Like That), but almost exclusively in Latin American countries. However, with his 2018 debut album X 100PRE, the singer got into the US market, boosted by his collaboration with Cardi B in the song “I Like It.”

Bad Bunny’s second solo studio album, YHLQMDLG (Yo Hago Lo Que Me Da La Gana, Spanish for I Do Whatever I Want), was an expansive and eclectic twenty-track release that included the participation of the recognized reggaetón producers Chris Jedi, Nesty, and Tainy. It debuted at number two on the US Billboard 200, and was recognized by national popular media as one of the fifty best albums of 2020. It went on to win the Grammy for Best Latin Pop or Urban Album category, and to become the year’s most streamed album on Spotify globally.

“Safaera” (Listening Guide 10.7), the fourteenth track on YGLQMDLG is a perfect example of Bad Bunny’s musical inspirations, his commitment to reggaetón tradition, and his capacity to move between musical genres. In many ways, “Safaera” is a heartfelt tribute to what’s known as reggaetón’s “old school”: it samples from several reggaetón classics; it incorporates “old school” percussion sounds, and it features senior figures like Ñengo Flow and Jowell & Randy. In terms of musical structure, “Safaera” references the early 2000s by incorporating marroneo, a song form characterized by frequent changes in tempo and instrumentation.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the song’s popularity was fueled by viral videos of people dancing to it, several of which had knowing winks to the song’s sexual references. Its popularity only grew when Spotify temporarily removed it from the platform. The reason was that Bad Bunny had been hit with copyright infringement lawsuits for uncleared use of samples of a Missy Elliott song and a mixtape by DJ Playero.

Latinos or Hispanics, the two terms used in the United States to refer to people of Latin American ancestry living in the country, totaled an estimated 63.7 million people as of 2022. At 19.1 percent of the total U.S. population, they are the country’s largest ethnic minority. If the U.S. Latino communities lived in a separate country, it would be the third-most-populous nation in Latin America. People of Mexican and Puerto Rican ancestry still predominate among Latinos, in 2022, accounting for 61 percent and 15 percent of the total demographic, respectively. However, shifts in immigration beginning in the 1990s led to a marked increase in new migrants from Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, and El Salvador—a group collectively referred to as “new Latinos.”

A common misconception about U.S. Latinos, partly fueled by the growth of “new Latino” immigration, is that most Latinos are foreigners. In fact, people of Latin American heritage have been living and making music in what is now U.S. territory since the sixteenth century, and more than 60 percent of Latinos in the United States today were born there. Some artists make music primarily for Latino audiences, while others aim to cross over to the mainstream Anglo market. Some emphasize their Latin American heritage, while others downplay it. Latinos have been instrumental in the development not only of Latino popular music styles, such as New York City salsa, Texas conjunto, and Los Angeles Chicano rock, but also of styles traditionally considered Anglo, like rock and roll, country, and hip-hop.

This section focuses on twenty-first-century popular music created by U.S.-born Latinos for Latino audiences. The Listening Guides represent three of the largest Latino groups: Mexican Americans, stateside Puerto Ricans, and Dominican Americans. Each of the next three guides—illustrating cumbia tejana, salsa romántica, and urban bachata, respectively—presents a modernized version of a Latin American style studied in previous chapters. The artists behind these innovations are bilingual and bicultural second- and third- generation Latinos. They have hybridized Latin American genres, fusing them with contemporary rhythm-and-blues and hip-hop elements to make them more appealing for urban U.S. Latino audiences.

U.S.-born Mexican Americans—that is, the descendants of Mexican immigrants—have a considerably different experience from that of the undocumented migrants just discussed. Second-generation Mexican Americans have historically assimilated well into U.S. Anglo culture. Research has shown that second-generation Mexican Americans speak English better than they do Spanish and regularly move out of immigrant neighborhoods into multiethnic ones. This process plays an important role when it comes to musical preferences. For many second-generation Mexican Americans, their first music interests are styles in English, such as rock and hip-hop, not Mexican music in Spanish.

Many U.S.-born Mexican American musicians first performed Anglo styles like rock and roll and country and only later embraced their Latin American heritage. Examples include Ritchie Valens, Freddy Fender, Los Lobos, Selena Quintanilla, and Los Lonely Boys. Their stories speak loudly of their complex bicultural worlds. For example, the great tejano singer Selena Quintanilla, born in Lake Jackson, Texas, in 1971, started singing in English and only reluctantly switched to Spanish at the request of her father, who thought that she had a better chance of success by targeting Spanish-speaking Americans than by aiming for crossover to Anglo audiences. In her early Spanish-language recordings, Selena did not understand what she was singing, so her father had to coach her. Selena began to fulfill her long-time dream of recording an album in English only after she had secured a massive fan base among Mexican Americans. Sadly, she never saw the project to fruition because a fan shot and killed her in March 1995 while she was still working on the album.

After Selena’s passing, the torch of hip tejano music passed to her older brother, A.B. Quintanilla III (b. 1963), who played in Selena’s backup band and also composed several of >her hits. In the new millennium, Quintanilla has enjoyed widespread popularity with his band Kumbia Kings. The Kumbia Kings updated the tejano sound by replacing the traditional sparse production used in Selena’s early 1990s albums with elaborate techniques and studio effects typical of contemporary rhythm-and-blues, hip-hop, and boy band music. Kumbia Kings vocals also borrow extensively from smooth rhythm-and-blues crooners like Usher or Ne-Yo.

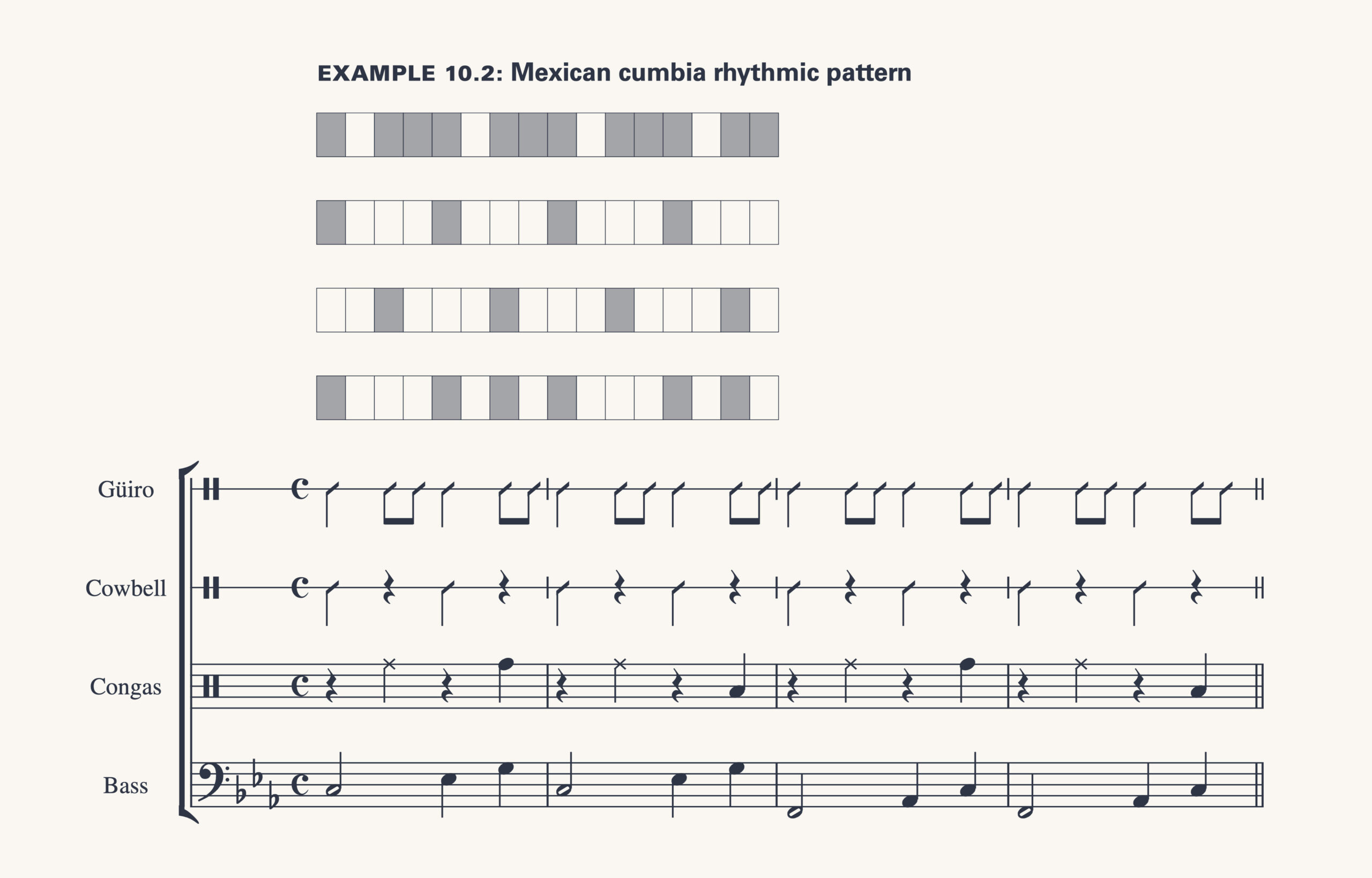

True to their name, Kumbia Kings often feature the cumbia rhythm in their dance- oriented songs. Cumbia is a style originally from Colombia’s northern coast that, in the mid-twentieth century, became popular throughout Latin America. In previous chapters you have encountered various local variants, such as Argentinean cumbia villera (Chapter 7), Peruvian cumbia andina and technocumbia (Chapter 8), and Mexican cumbia (Chapter 3). The Mexican variant is markedly simpler than Colombian cumbia. The original polyrhythms are replaced by a straightforward rhythmic pattern and small combos (grupos) consisting of electric guitar, electric bass, organ/synthesizer, güiro, and drum set take the place of traditional big bands. Example 10.2 shows Mexican cumbia’s core rhythmic pattern. Note that in the conga line, the two pitches in blackheads represent open tones on two conga drums, one tuned higher than the other. The golden age of Mexican cumbia spans the 1970s and 1980s, with groups such as Los Bukis and Bronco. Kumbia Kings can be considered a modernized version of such groups.

In 2003, Kumbia Kings released the album 4 in which they mix cumbia, reggae, vallenato, rhythm and blues, and hip-hop. The album’s first half features songs in Spanish, while the second half is in English. The third single released off the album is an exciting collaboration, co-written and co-performed by Kumbia Kings and critically acclaimed alternative rockers Ozomatli, a Los Angeles, California, band that formed in the mid-1990s and is known for its musical hybridity. In Nahuatl, an indigenous Mexican language, Ozomatli refers to a figure in the Aztec sun calendar and to the god of dance. While borrowing most consistently from Latin American dance rhythms, the multiracial band incorporates elements from various world music sources. In the following quote, Ozomatli’s Mexican American trumpet player Asdrubal Sierra, jokingly describes what an ad for the band would look like:

Looking for a classical Indian music/tabla player of Japanese decent; a Jewish American bassist influenced by Sly and Robbie; a Mexican guitarist that can play Cuban tres, a strat, a Veracruzan jarana; a half Spanish/Mexican tenor sax player that doubles on requinto jarocho and piano; and a Mexican American singer who can sound Middle Eastern, gitano [Gypsy], salsa, or rock in English or Spanish—play trumpet is a must.

Before collaborating with Kumbia Kings on “Mi gente” (My People, Listening Guide 10.8), Ozomatli’s 2001 album Embrace the Chaos won the Grammy for Best Latin Rock/Alternative Performance. “Mi gente” (Listening Guide 10.8) thus represents a collaboration between the hit-making, chart-topping Kumbia Kings and the less commercially successful but critically acclaimed Ozomatli (Figure 10.9). The song also bridges the gap between the Latino cultures of Texas and Southern California.

“Mi gente” takes inspiration from first-generation immigrants. It tells the story of a migrant worker who comes to the United States following a promise of opportunity. He wonders, “if I’m honest and I work from dawn until dusk, why am I treated like I don’t belong here?” The infectious chorus expresses a string of contradictory emotions: “I suffer, feel, laugh, cry, don’t speak up, scream, with my people…because they don’t understand me.” The song opens with a striking mix of hip-hop scratching, Brazilian cuica friction percussion, Caribbean timbales, and Mexican accordion. The bridge section borrows from Jamaican dancehall and is followed by a bluesy electric guitar solo and a jazzy trumpet line. The music video combines scenes of Kumbia Kings and Ozomatli performing (separately) with footage from the Chicano rights movement of the 1960s. The video brings home the song’s message of unity, ending with the image of a wall graffiti that reads “Brown is together.”

Much has happened since the golden age of the raw and edgy sound of 1970s New York City salsa discussed in Chapter 5. After a rough patch in the 1980s when Dominican merengue dominated the East Coast Latino club scene, salsa came back in full force with an updated, smoother sound and an aesthetic that made it more commercially successful than ever before. In the twenty-first century, salsa artists like Marc Anthony and La India have begun to close the gap between the hard-driving barrio salsa of the 1970s and the romantic spirit of the 1990s.

The 1980s was a trying decade for salsa. It started with the closing of Fania Records, the epicenter of salsa production in the 1970s and, to many, the label that created the best salsa records ever produced. As Latino youth turned to Dominican merengue and the new Bronx style later known as hip-hop, salsa became “old-folks’ music.” The most successful effort to modernize salsa came from the collaboration of arranger Louie Ramírez and producer Isidro Infante. They came up with the idea of recording cover versions of already-popular baladas (romantic pop ballads, a style wildly popular across Latin America that is associated with soap opera soundtracks) using salsa arrangements.

This new style, first known in Puerto Rico as salsa sensual and in New York City as salsa romántica, differed from the Fania model in a number of important ways. First, it avoided the Spanish Harlem–centered and politically charged lyrics of 1970s salsa. Even as the style moved beyond cover songs and new ones were composed, the lyrics dealt mostly with romantic themes. Second, a smooth-sounding crooning style of singing replaced the nasal quality of 1970s salsa vocals. Third, the brash, rough-around-the-edges sound of the salsa bands, particularly of the brass and percussion, was replaced with a polished and refined sound molded in the studio. Finally, salsa romántica shifted the attention from the bandleader to the singer, and from improvised lead vocals in the montuno to entirely precomposed songs. Instead of experienced soneros, most salsa romántica featured youthful and attractive singers that appealed to younger audiences.

In 1987, concert promoter Ralph Mercado founded the label RMM Records with the purpose of recording and marketing this new style of salsa. RMM’s music directors, Isidro Infante and Sergio George, are largely responsible for shaping the salsa sound of the 1990s and are behind the success of a cadre of singers, including Tito Nieves, La India, Marc Anthony, and Johnny Rivera. Infante and George aimed at crossover, but not in the traditional sense of pushing a Latin/o American style into the mainstream United States. Their goal was primarily to cross over into Spanish-speaking Latin/o American communities. As previous chapters in this book demonstrate, musical preferences vary widely across Latin America, making hemispheric crossover a challenging enterprise few artists have achieved. While purists continue to mourn the death of the classic Fania salsa of Willie Colón and Héctor Lavoe, RMM’s formula produced the best-selling salsa artists of all time, and, notably, brought to fruition Fania’s dream of a pan–Latin American embrace of salsa.

One of the most compelling singers in the RMM roster was Nuyorican La India (b. Linda Viera Caballero in 1969) (Figure 10.10). Like many young second-generation Nuyoricans in the 1980s, La India initially rejected salsa because she considered it old-fashioned and corny. She started her music career singing in English in the house music scene, and only turned to salsa after encouragement from salsa singer Héctor Lavoe. Her breakthrough album, Dicen que soy (1994), is a perfect example of producer Sergio George’s new approach to salsa. George combined La India’s soulful rhythm-and-blues vocals (including melismas and blue notes), covers of famous baladas arranged as salsa, and elements of hip-hop and house music. The winning result was somewhere between the 1970s “hard salsa” and 1980s salsa romántica; the lyrics were too romantic and melodramatic to be “hard salsa,” and the singing too fiery and intense to be salsa romántica. (Dicen que soy closes with an exciting duet with then up-and-coming Marc Anthony, called “Vivir lo nuestro,” roughly “Live Our Lives”).

A comparison of La India’s 2002 song “Sedúceme” (Seduce Me, Listening Guide 10.9) with the salsa song included in Chapter 5, Celia Cruz and Ray Barretto’s “Ritmo en el Corazón,” will help us elucidate the new features of twenty-first-century salsa. While “Ritmo en el Corazón” is not a classic salsa from the 1970s golden age, it serves our purpose here because in 1988, when it was recorded, the song looked back nostalgically to earlier decades, as represented by two older and well-established artists. “Ritmo” celebrates tradition both lyrically and musically. Celia Cruz sings about her undying passion for music while outlining the history of salsa, from Africa to Cuban son and rumba. Musically, the song acknowledges the two main sources for salsa, Cuban son and Puerto Rican bomba.

Like many salsa romántica songs, “Sedúceme” contrasts stylistically with older repertoire, represented by songs such as “Ritmo en el corazón.” It opens with an airy keyboard and synthesizer introduction reminiscent of late 1990s boy-band production; only twenty seconds into the song, with the entry of the percussion, do we realize that this is actually going to be a salsa number. Also characteristic of salsa romántica is the fact that the song is about heartbreak and seduction rather than tradition or politics. In “Sedúceme,” the singer pleads for a final night of passion with her lover before parting ways. There are no references to salsa’s history except for a clever allusion to the title of La India’s own duet with Marc Anthony, “Vivir lo nuestro.” The target audience for “Sedúceme” is a younger crowd that is open to salsa, yet may not be interested in thinking about it as a style with a long history or a political one.

The crisp, clear pop sound of songs like “Sedúceme” is the result of over-dubbing, a recording technique in which each part is recorded individually, and the final song is produced by layering the tracks. The downside of overdubbing is that it limits opportunities for improvisation and interaction among musicians that can occur in live performances. Ray Barretto’s own opinion was that most of the young salsa singers who emerged in the early 1990s were unable to sonear, to improvise in rhyme like classic salsa singers could. While La India has developed into a great vocalist in terms of her overall abilities, improvisation plays a less central role in her music than it did with earlier performers. When I saw La India performing live in Philadelphia in 2003, “Sedúceme” was the show’s climax. She belted the song out with aplomb and passion, making everybody in the audience move. Yet her soneos in the montuno section were identical to the recording, and so were the brass section’s moñas. Old-timers may resent the declining role of improvisation in salsa, yet nobody in the audience at that show, including me, seemed to mind.

The “pop” quality of this new salsa is only part of the reason why it resonates with younger-generation Latinos. Most importantly, for many second-generation Latinos, this new salsa resonates with their bilingual and bicultural experience. It allows them to reconnect with their heritage without giving up their hard-earned right to assimilate into U.S. society.

As of 2021, Dominican Americans are the fourth-largest Latino population in the United States. Unlike the Latino groups just studied, most Dominican Americans are first-generation immigrants. In fact, over half of the Dominican American population arrived in the United States after 1990. The economic, political, and cultural importance of the Dominican Republic’s U.S. diaspora is undeniable. As George Lipsitz notes, Dominican political candidates campaign in New York City, Dominican political parties have offices in the United States, and the remittances of Dominicans abroad shape the country’s economy.

A music style that beautifully illustrates the transnational nature of contemporary Dominican identity is bachata. As outlined in Chapter 5, bachata is traditionally a Dominican acoustic love ballad characterized by its lyrics about heartbreak and quick, high-pitched, lilting countermelodies on the lead guitar. It originated in the 1960s as a local variant of the Cuban and Mexican bolero and Puerto Rican jíbaro music. As Dominican immigration to the United States skyrocketed in the 1990s, the musical preferences of migrants, with their higher incomes, began to shape the Dominican music industry from abroad. In the new millennium, as Deborah Pacini Hernandez explains, it is Dominicanyork bachata that dominates the scene in both countries, rather than the other way around.

By far the most influential and commercially successful Dominicanyork bachata group is Aventura, a quartet formed in the mid-1990s in the South Bronx. Aventura’s breakthrough came in 2002 with the hit “Obsesión,” which topped the charts in places like Italy and Germany and helped define their bicultural style. The “Kings of Bachata,” as they call themselves, modernized bachata by adding melismatic rhythm-and-blues singing, rapping in English and Spanglish, collaborating with reggaetón artists, and adopting a hip urban fashion sense and a big-city attitude. In the words of frontman Anthony “Romeo” Santos, Aventura “put the cool in bachata.”

Musically, the most recognizable features of Aventura are Romeo’s suave and expressive falsetto and Lenny Santos’s rapid-fire guitar countermelodies. Aventura follows a trend that started in the 1990s of composing bachata with clean, family-friendly lyrics and marketing it to young women. Lead singer Romeo unmistakably addresses his song lyrics and frequent ad-libs to women. The band presents a striking combination of old and new, rural and urban sensibilities. All their major hits are essentially acoustic bachatas accompanied by guitar and light percussion on bongos, congas, and güira (a metal version of the gourd güiro preferred by Cuban and Puerto Rican performers). Their gallantry is definitively old- fashioned, and tame in comparison to hypersexualized rap and reggaetón. Yet their looks are unquestionably urbane: designer jeans and tight shirts, shiny bling, and light-colored suede.

So far, Aventura has not crossed over to the mainstream U.S. market. Arguably, however, the massive audience that follows the group challenges the very concept of mainstream. In early 2010, Aventura played four sold-out concerts at New York City’s Madison Square Garden, a feat unheard of since Madonna’s peak in the 1990s. By comparison, Lady Gaga sold out that same month for four nights, too, but in Radio City Music Hall, a much smaller venue. By 2021, the band helmed its first no. 1 on the Billboard Hot Latin Songs chart with the song “Volví,” featuring Bad Bunny. If bachata was a niche market, it is now part of the mainstream.

The flow between homeland and diaspora is circular. The same technological advances that allow immigrants to stay connected to their homeland permit the reverse flow of music back to the sending country. First-generation Dominicans brought bachata with them. Second-generation Dominicanyorks, like the members of Aventura, are sending it back, transformed, as a cultural remittance. In 2010, Aventura presented the same show they developed for the U.S. market to a sold-out Santo Domingo arena; fans fainted and critics raved.

In 2009 Aventura dominated the Billboard Latin charts with their album The Last. Its massive popularity landed them an invitation to perform at the White House for a televised concert hosted by President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama in celebration of Hispanic Heritage Month. Aventura’s members were the only performers who were not from the three historically dominant U.S. Latino communities: Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Cuban Americans. At the White House they performed their bachata “Su veneno” (Her Venom, Listening Guide 10.10), the third single off The Last.

This chapter has explored contemporary Latin/o American popular music, emphasizing the concept of hybridity and the interconnections that exist across the Americas. All the artists in this chapter can be described as having one foot in Latin America and one in the United States. For contemporary Latin American artists, the U.S. serves as an attractive center of music production and, given the size and economic power of the Latino community in the United States, a highly profitable market as well. For U.S.-born Latinos, on the other hand, Latin America remains an important source of musical inspiration and a powerful referent for the construction of Latino identities.

This chapter has also addressed the impact of migratory trends on popular music. In the future, migration is expected to continue to be a transforming force in both Latin America and the United States (some estimate that by 2050, U.S. Latinos will account for 30 percent of the country’s population). Through economic and cultural remittances, diasporic communities’ influence in their originating countries is likely to persist, if not grow. In the United States, it is conceivable that the growth of the Latino population will lead to an increase in inter-Latino interaction. Stronger bonds across U.S. Latino communities may contribute to a weakening of national identification with countries of origin. In its place, we may find a bolstered sense of Latinidad. The music that will speak to these new identities remains to be heard.

assimilation

balada

cosmopolitan

cumbia tejana

dancehall

falsetto

hybridity

inter-Latino

Latinidad

música norteña

narcocorrido

corrido tumbado

New Latinos

Nor-tec

overdubbing

regional Mexican music

remittances

salsa romántica

trap latino

tejano

Texas-Mexican conjunto

urban bachata

Cepeda, María E. Musical ImagiNation: U.S.-Colombian Identity and the Latin Music Boom. New York: New York University Press, 2010.

Flores, Juan. The Diaspora Strikes Back: Caribeño Tales of Learning and Turning. New York: Routledge, 2008.

Hankin, Charlie D. Break and Flow. Hip Hop Poetics in the Americas. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2023.

Madrid, Alejandro L. Nor-tec Rifa!: Electronic Dance Music from Tijuana to the World. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Madrid, Alejandro L., ed. Transnational Encounters: Music and Performance at the U.S.–Mexico Border. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Pacini Hernandez, Deborah. ¡Oye como va!: Hybridity and Identity in Latino Popular Music. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2010.

Rivera, Raquel, Wayne Marshall, and Deborah Pacini Hernandez. Reggaeton. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009.

Rivera-Rideau, Petra R. Remixing Reggaetón: The Cultural Politics of Race in Puerto Rico. North Carolina, Durham: Duke University Press, 2015.

Rivera-Servera, Ramón. Performing Queer Latinidad: Dance, Sexuality, Politics. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2012.

Valenzuela Arce, José Manuel. Corridos Tumbados: Bélicos Ya Somos, Bélicos Morimos. Guadalajara, México: NED Ediciones, 2024.

Chulas Fronteras. Les Blank, director. Arhoolie Records, 2003 [1976].

De La Calle. Nick Barili, Yvan Iturriaga, and Alexandra Posada, directors. Hard Knock TV, 2023.

Juanes, Origen. Kacho López Mari, director. Universal Music, 2021.

Latin Music USA. Jimmy Smits, Adriana Bosch, et al., directors. PBS Distribution, 2009.

Residente. Residente, director, and Alexandra Posada, cinematographer. The Orchard, 2017.

The Boy from Medellín. Matthew Heineman, director. Amazon Studios, 2020.

Composers: Shakira, Luis F. Ochoa

Lyricist: Shakira, Alejandro Sanz

Date of recording: 2005

Performers/instruments: Shakira with Alejandro Sanz; accordion, electric and acoustic guitars, electric bass, Cuban tres, keyboards, drums, and percussion

Form: strophic verse–chorus with bridge

Tempo/meter: moderate dup

What to Listen for

Time

0:00

Track

Ay payita mía...

Translation

Hey girl...

Description

Entrance of reggaeton beat, together with an electronically echoed acoustic guitar and an electric guitar playing chords on beat 2 (the backbeat) during the introduction. Later, bass and accordion play over the same beat, imitating cumbia vallenato (see Chapter 4).

Time

0:19

Track

No pido que todos los

días sean de sol...

Translation

I don’t ask forun

shine every day...

Description

tripped-down verse section features female oice prominently as well as accordion chords and sparse percussion hits; ther instruments silent

Time

0:39

Track

Ay amor me duele

tanto...

Translation

Oh, love, it hurts so

bad...

Description

Pre-chorus, with vocal harmonies; entrance of bass with tresillo pattern over reggaeton beat; guitar plays sparse, occasional chords

Time

0:54

Track

Yo sé que no he sido

santo...

Translation

know I haven’t been

a saint...

Description

Chorus; full ensemble sound featured with skanspired backbeats on the electric guitar, along with reggaeton rhythm and heavier bass pulse on strong beats

Time

1:22

Track

No puedo pedir que el

invierno...

Translation

I can’t expect winter...

Description

Verse; music becomes sparser again, with reggaeton pulse and bass prominent, but less drum set and guita

Time

1:42

Track

Ay amor me duele

tanto...

Translation

Oh, love, it hurts so

bad...

Description

<b<Pre-chorus; Cuban tres plays prominent fills

Time

1:56

Track

Yo sé que no he sido

un santo...

Translation

know I haven’t been

a saint...

Description

Chorus; full ensemble sound featured again; ccordion solo at 2:16

Time

2:25

Track

No te bajes, no te

bajes...

Translation

Don’t let go, don’t let

go...

Description

Bridge; most instruments fall silent for a time, except male voice and bass; slow buildup of pulse and percussion again

Composer/lyricist: Juan Esteban Aristizábal Vázquez (Juanes)

Date of recording: 2007

Performers/instruments: Juanes; electric guitar, keyboards, electric bass, drums, and percussion

Form: strophic verse–chorus

Tempo/meter: moderate duple

What to Listen for

Time

0:00

Track

Translation

Description